A rising generation of young martial artists are hoping to drop kick their way onto the big screen.

KAMPALA, Uganda—

The red dirt road through Wakaliga is slick and wet with morning rain, staining the shoes and socks of travelers the color of dried blood. Commuters tiptoe carefully around the slippery streets, but Racheal Nattembo dashes fearlessly through them. The determined young girl is late for kung fu practice and has no time to fret about cleanliness.

She stops in front of Nateete Mixed Academy, a rundown school at the heart of the slum in the Ugandan capital. She fumbles with her shoelaces before entering the compound where five of her classmates are already practicing. The 8-year-old joins her peers in formation, practicing their moves.

“I like kung fu to act in movies,” Racheal tells me, wiping the rain away from her face. “It is fun—the best part is kicking.” She aims a swift kick at her invisible opponent and ducks in anticipation of a retaliatory blow.

I’ve been invited to watch the practice by Charles Bukenya, a kung fu master with more than 10 years of experience, who has trained the children since 2013. But the objective of their training isn’t to master self-defense, I quickly learn—it’s to tap into the soaring popularity of martial arts movies in Uganda.

Over the last 10 years, the local film industry, also known as “Ugawood,” has grown exponentially with increased access to technology and international distribution via the Internet. There are more than a dozen active films companies in Uganda today, nearly all of which were founded between 2000 and 2014. It is now estimated that Ugawood produces roughly 30 films per year, and while the movies span across all genres, action and martial arts rate among the most popular.

“If you see Western movies, it’s full of action which is dominating now here in Africa,” says Isaac Nabwana, founder of Ramon Film Production in Wakaliga. “Martial arts are rising and everyone now is trying to do what I’m doing because they see I’m doing something that is unique and is loved.”

The next generation of the film industry in Africa

Though the first official Ugawood movie was released in 2005, Isaac’s 2010 film called Who Killed Captain Alex? is widely credited as the country’s first action feature. His latest kung fu film, This Crazy World stars Rachael and her classmates in their big screen debut and went straight to DVD in 2014 under the local title, AniMulalu, or Crazy People. The movie features the young Wakaliga martial artists and their daring escape from child sacrifice rituals.

“I played Liz,” says Racheal excitedly, aiming a punch at a crumbling fence. “She was fighting to go back where she was living.” Isaac believes these children are not only the future face of the country’s film industry, but also evidence of a rising martial arts mania that is sweeping the city streets of Kampala.

Since 2006, the director has made more than 10 films, but none have sold better than This Crazy World. He attributes the movie’s success not only to its junior actors, but to its overarching kung fu theme. “I think this is going to be the next generation of the film industry in Africa at large,” he says.

When a new Ugawood movie is released in Kampala, it goes straight to DVD and is sold door-to-door until a movie theatre or cinema hall, picks it up for a public showing. Since 2005, the industry has pumped out a number of well-known local martial arts actors including Kizza Ssejjemba, Dauda Bisaso, and the children’s trainer, Charles Bukenya.

“They will be good actors and actresses because they love what they are doing,” says Charles, inspecting the children’s movements for errors in technique. “I think they knew nothing about Kung Fu and now they are good, they are trying.” The trainer is one of Uganda’s first martial arts movie stars, having acted in both Who Killed Captain Alex? in 2010 and The Return of Uncle Benon in 2011.

Martial arts are not new to Africa; Nubian wrestling, which is depicted in ancient Egyptian art as early as 2300 B.C., is believed to be a predecessor to Greco-Roman wrestling. And Zulu stick fighting appears in written history nearly four millennia later as warfare training for Northern Nguni men in 19th-century Southern Africa.

In Uganda, Asian martial arts were first introduced in the late 1960s, when, according to the Uganda Taekwondo Federation, a special instructor from South Korea was invited to teach inmates at the Uganda Prisons Headquarters in Luzira. Country Wing Chinese Martial Arts, a famous academy that has more than 10 affiliates across East Africa, records kung fu in Uganda in the late 1990s, but believes it may been practiced on an individual basis as early as 1988. Today, the country is home to a handful of Asian fighting styles including wushu, karate, tai chi, and kickboxing.

To learn more about the snowballing martial arts movement, I make my way across town to a Country Wing Chinese Martial Arts school in Kampala, where Peter Wamala, a short but burly kung fu instructor, is waiting for me on a set of red practice mats. I’m surprised to find him in a dress shirt and slacks as he sits patiently in the outdoor gym. “Martial arts are popular now maybe because we are publicizing it and Ugandans are getting more exposed,” he explains, making space for me on the floor. “Other continents like Asia, Europe, and America are having more people here and then also the media is now more open.”

Today, the capital city is home to at least five major martial arts schools with expert instructors from all over the world. Country Wing has been operating in Uganda 1997 and has opened three local training centers to meet the growing demand. Here in the Kololo branch, Peter’s students have more than tripled in the last five years—from 10 to 15 students in 2009 to as many as 50 today. “Generally the communication between the West and us here has made it popular,” he says. He adds, “As people’s lives are improving they get more concerned about health.”

Growing up, the 30-year-old remembers having access to only one television channel and a couple of censored local radio stations.

Computers were rare, there was no Internet and exposure to foreign culture was limited. Now, Ugandans have access to more than 20 TV channels, eight newspapers, and 100 radio stations, providing increased coverage of international trends in sport, fitness, and film culture. The Uganda Communications Commission estimates there are more than 8.5 million Internet users in the country today, up from about 4.5 million in 2010. Adding fuel to the fire are thousands of pirated movies from around the world, which sell for as little as 60 cents each on roadside stands throughout Kampala. And according to those in the local film industry, martial arts movies are a top-seller.

“They watch Hollywood movies,” says Kuraisn Baale, a Taekwondo champion and gym owner in Katwe slum, not too far from Wakaliga. “So now here in Uganda you act in a movie with martial arts style and most of the Ugandan people get interest of it.”

Kuraisn started his company, Good Hope Gym and Movies Industry, a few years ago not only to improve fitness in his community, but to piggyback on the success of the kung fu craze. His facility offers acting as well as combat lessons. He says sometimes, the acting is more popular than the physical activity. “Martial arts here in Uganda in terms of tournament, it’s not popular but in the movie acting it’s popular,” he explains. “Here in Uganda people are now interested in martial arts because they want to act in movies.”

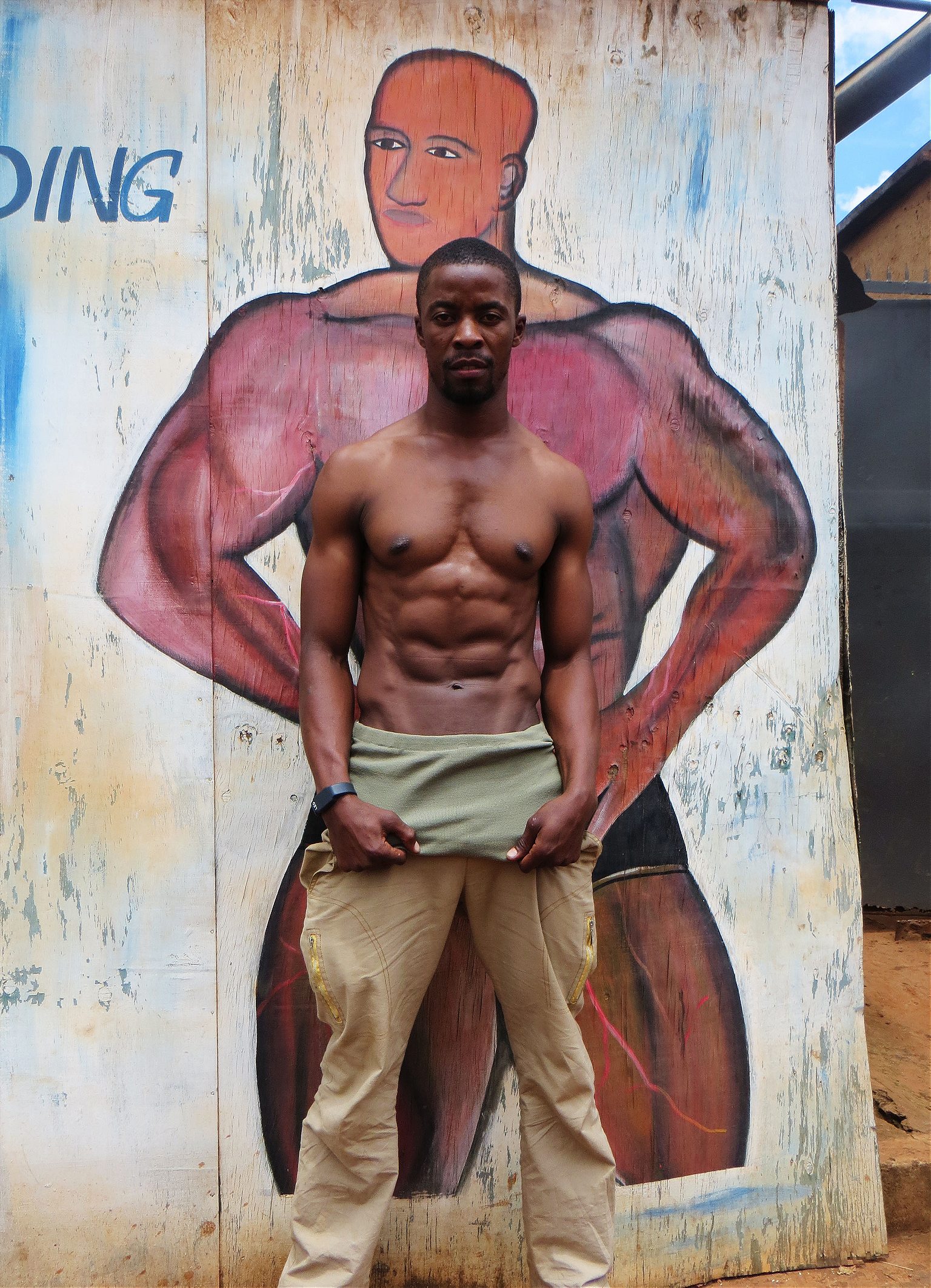

Kuraisn’s younger brother Muhammad is a prime example; in 2012 he started kickboxing with the hopes of becoming the country’s newest martial arts movie sensation. The chiseled 27-year-old has since had roles in six local movies, but aspires to break into the international film industry. “First of all, I want to be famous,” he says, pausing his workout to show me a collection of DVDs with his face on the cover. “But I love martial arts because it is a game that is technical; you can fight against 10 people or five people.” He gives me with a copy of Honeymoon, his latest romance-action film about a woman’s affair with her undercover bodyguard, before returning to his set of rusty metal hand weights.

I hop on a boda boda, a motorcycle taxi, back to Wakaliga, taking note of every gym I see along the way. Images of famous fighters cover their windows, which advertise weight loss, self-defense, and film acting classes. The schoolyard at Nateete Mixed Academy is quiet now and the kung fu children of Wakaliga appear to have finished their practice. Only Racheal lingers behind in the playground attacking her invisible opponent to make up for her lateness earlier this morning.

“It is not difficult,” she says, observing my admiring gaze from the gate. The 8-year-old is now balancing on one foot as she moves her arms through the rest of her sequence.

Beads of sweat drip down her forehead; the rain has stopped and the sun is scorching. She tosses in a few extra punches, silently counting the moves as she goes. Racheal may be a fearsome fighter on screen, but here in the schoolyard, she is still a student. The class in kung fu, the curriculum is combat, and her test will come in front of the camera.