In central Moscow, a famous and slightly foreboding institution is finding new life under restaurateur Alexei Zimin.

I am struggling to keep up with restaurateur Alexei Zimin as he shows us around a Tsarist mansion annexed in Soviet times to serve as the dining hall for the Central House of Writers. The beam of his flashlight skitters over dusty parquet floors where Tolstoy’s characters once danced and Bulgakov’s Devil dined; as we rush underneath, he points to the crystal chandelier Stalin gave to Maxim Gorkiy. We only stop once, on a staircase, so Zimin can explain a door. The U.S. Secret Service, he says, required staff to cut the door into the wall as an emergency exit, just in case, for Ronald Reagan when he dined here with Mikhail Gorbachev. But we are still a month or more from the grand reopening of this space (which finally happened earlier this April), so the door is closed, as is everything else, while Zimin recasts the mansion as a bright new welcoming restaurant.

THE WAITERS WERE ALL RUMORED TO BE ON THE PAYROLL OF THE KGB

It’s worth pointing out how little the word “welcoming” typically belongs in the same paragraph as “Central House of Writers.” Context: the waiters were all rumored to be on the payroll of the KGB. Context: in 1978, dissident writer Yury Dombrovsky was beaten so badly just for walking into the lobby here that he died six weeks later. Context: the restaurant only opened to the public in the 1990s as a blingy New Russian joint, and then managed by aristocratic Disneyland-builder Andrey Dellos, who filled it with white-gloved waiters and red damask tablecloths before he inexplicably walked away and left the building to its fate.

Our tour through ЦДЛ (the Cyrillic acronym TzDL that the place is known by) is rushed, but not because Zimin is nervous about the daunting task before him. I suspect it’s because we’ve already ordered appetizers and he doesn’t want them to get cold.

Zimin edits Afisha-Eda, arguably the first decent food magazine in the former Soviet Union. Readers turn to him for everything from wisdom on making plain omelets to 58 ways to prepare borscht. After training briefly as a chef in London, he started a mini-empire of casual restaurants in Moscow. He has done something that almost no one else has managed to do: serve food that is fresh, unpretentious, and also Russian. Not faux-French, not faux-Japanese, not Georgian or Central Asian, but Russian—a cuisine battered for 70 years by a command economy, war, food shortages, communal kitchens, school and worker cafeterias, and unspeakable rivers of cheap mayonnaise.

Through all those challenges, Russians have managed to keep small corners of unadulterated, undiluted Russian food alive for themselves, at least on special occasions. Homemade dumplings—pelmeni—for a New Year’s Day party or a “Salad Vinagret” of fresh new beets and dill: Zimin is just elevating and reinforcing that folk knowledge with professional knowhow and cheerful determination. But he has his work cut out for him at ЦДЛ. The public restaurant in front may have gone Euro-snobby after Perestroika, but the private “Art Club” in back had remained a model of high Soviet style. He’s taken over both—they share a kitchen now—but when I visited, the public restaurant was still under its long renovation.

ZIMIN FIRED ALL THE PREVIOUS STAFF HERE AND CUT THE MENU IN HALF

So we rush to the private club side via the underground kitchen filled with shiny refrigerators. The club’s dining room is a vast windowless box, set with Stalinesque gold columns, tall curtains and salmon-pink walls. Zimin fired all the previous staff here and cut the menu in half.

“I tossed all the things that I couldn’t figure out,” he tells me in his stuttery Russian. For example? “For example, salads with romantic names, according to notions of fine cuisine of the 1970s.” For example? “Shrimp with ketchup, some kind of fish, various salad greens, potatoes, carrots.” Mixed altogether with mayonnaise, no doubt, the salad was called Inspiration.

Zimin killed Inspiration, but he kept the stalwart standards of the Soviet menu: the Salad Olivier (peas, ham, potatoes, mayonnaise); Salad Mimoza (rice, tuna, carrots, green onions, eggs, mayonnaise); Forshmak, a Jewish/German/Swedish import (herring, bread, apples, eggs, butter).

My dining companions all grew up in the Soviet Union, and they get visibly excited at the sight of Zimin’s menu and the lightened, reinvigorated dishes that arrive at our table. “I see this menu and I want it all,” says my friend Misha Smetana, Afisha-Eda’s art director and incidentally, a Ukrainian. “I see this and I start to …unh.” He rolls his eyes, sighs loudly, orders vodka.

I had actually come to Zimin with a question that seemed far too small for this astounding setting, but it’s a question that’s bugged me for years traveling the former Soviet Union: why is eating out here so hard? For me, at least. The food is getting much better thanks to Russia’s wealth and expanding taste; most wait staff is perfectly pleasant now and can even be helpful to foreigners. But I can’t get past the menu: no matter what kind of restaurant, it’s usually 250 or more items, arranged beneath a bewildering array of chapter headings including appetizers, salads, hot-dishes, cold-dishes, side-dishes, and sauces (ketchup is always in there, no matter the cuisine, and it always costs $1). It is too much information, augmented by government regulations that require every major ingredient to be portioned out in grams. I usually give up and just order blini with butter, sour cream, and roe (100/50/50/10), Salad Vinagret, mineral water and a side helping of shame.

“I once encountered a menu in Saratov that was 40 pages,” Zimin shrugs. “Russian diners like to feel like they have a lot of choices.”

But even without many choices, the four former Young Pioneers at the table with me are in ecstasy as we sample Soviet restaurant food that actually tastes good. The forshmak is molded from the tiniest slivers of hard-boiled egg; the airy pelmeni couldn’t be any more different from the doughy lumps of grease that might hit your plate in a cafeteria. This is not restaurant food at all, this is the food that grandma worked all summer to grow at the dacha, canning and bringing back home to build a banquet on New Years’ Day.

EVERYONE IS CONSTRUCTING A LONG-LOST BANQUET IN THEIR HEADS

It’s here I realize that Russian restaurant menus, even Zimin’s, are not a list of food at all. They present a set of coordinates for one to scan and match with the needs of the heart. Your heart might need Salad Olivier, because your aunt made it from scratch, and her home lay at the end of a 12-hour train ride and half-hour tram that smelled of exotic Central Asia, and you miss that trip. If you never traveled to such an aunt, never built your food life around the universal binding agent mayo, then you simply cannot order correctly from a Russian menu. No one is dining out on this cuisine just to eat—everyone is constructing a long-lost banquet in their heads.

Vodka does help, Zimin advises. “If you’re not drinking, it’s going to be hard for you,” he says. I am not drinking, but here, in this company, everything is still just perfect.

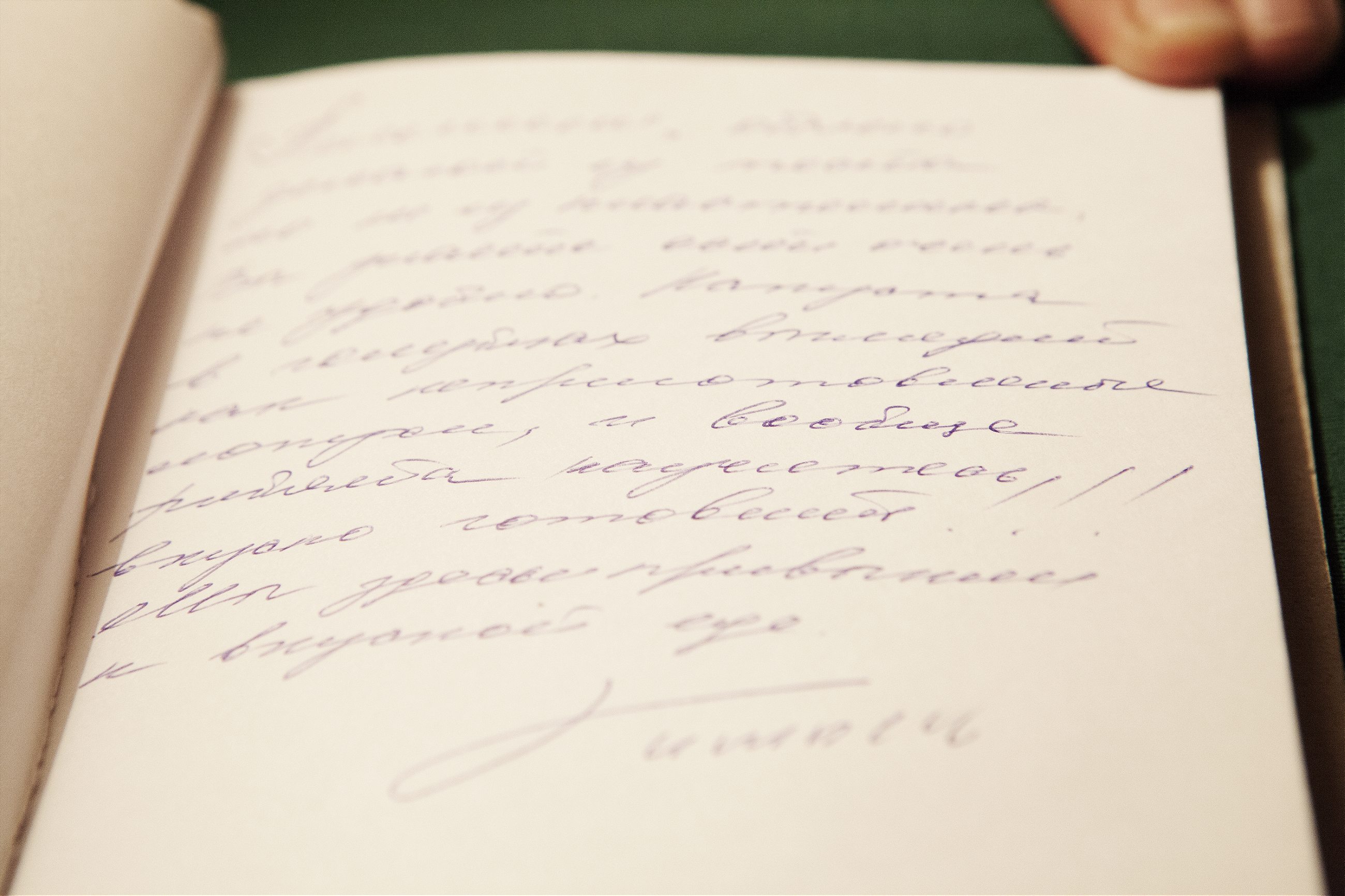

This would be a good place to end, with Zimin the hero of a revitalized, de-Stalinized, more accessible Russian cuisine complete with home-made mayonnaise. That is the trajectory he has set, and he seems sanguine about the long campaign ahead. But tonight, Art Club is nearly empty. Our check comes. Zimin has his staff put the bills in small, blank notebooks for feedback. We look at the notes left in ours, and are surprised to see that it is filled with aggressive notes left by other diners about the changes he has wrought thus far at Art Club and ЦДЛ.

“Why don’t you spend some time learning how to make tasty food?” writes one woman—it has to be a woman, judging from the impeccable Cyrillic script. “We used to know how to make tasty food here.” She signs her name with a great flourish. She is a writer, after all, and this is what writers do. Zimin takes the notebook from us and reads her screed. Ever the professional, he smiles like he’s just tried the most divine dish of all.