The debate about soccer’s rightful place in American culture opens a wider conversation about America’s place in the world.

In the build-up to the 2014 World Cup, Reuters released a poll claiming that two out of three Americans had no plans to follow the tournament. These sorts of findings point to the country’s “exceptionalism,” how the U.S. alone resolutely resists the allure of the world’s game. For some time, observers have been searching for theories to explain why the biggest economic, political and military power on earth has been a latecomer to soccer, and why the MLS Cup final continues to attract a tenth of the television audience as a weekend airing of Wheel of Fortune.

Critics of soccer often invoke the notion of American exceptionalism to provide the answer. A sport beloved of the entire world, we’re told, just has no place in America.

Because the United States was founded on a unique premise—free of feudal and class constraints and with the protection of individual liberties as the lone raison d’etat—it established a bourgeois society with nationalist sporting affinities that evolved in the presence of free markets and vibrant local communities, all in isolation from the world.

Because soccer is an imported product, with simple rules designed around the simple tastes of a proletariat that never existed, it has faced a perpetual struggle to be accepted as part of mainstream America. The NFL and college football, baseball, basketball, NASCAR, even ice hockey all dominate sporting discourse, as any flip through a U.S. newspaper, ESPN or sports talk radio will testify, because they continue to reflect the patriotic heart of American culture.

The collapse of the first North American Soccer League? Dismal ratings for Major League Soccer? The inability to get past Ghana in the World Cup? Exceptionalism. America’s different. Soccer struggles in America, and Americans struggle at soccer, for the same essential reason: because the country and its people are not really interested in a foreign, working-class, low scoring game that can end in a draw. Frank Deford, perhaps the most well-known purveyor of sports exceptionalism, once put it this way: “The reason that we don’t care about soccer is that it is un-American. It’s somebody else’s way of life.”

The reality, however, is that soccer has indigenous roots.

What to make, then, of the soccer fans in the country? The anti-soccer belief in U.S. exceptionalism dismisses them, caricaturing the American soccer fan at once as an isolated, hyper-enthusiatic newbie and as a superficial fashion-seeker with an elitist, foreign fetish—the elitism, in particular, being the element at which soccer’s dissenters most often recoil.

The reality, however, is not only that soccer has indigenous roots—from Ivy League and West Coast colleges to professional leagues in St. Louis—but has boasted a national community of fans at least since Pele arrived at the New York Cosmos in 1975. When the Roper Organization first began to poll Americans about the game the year before, they found roughly 1 in 5 expressing interest. Since then, little has changed.

Starting in 1994, and continuing through 2002 and 2013, polls by ABC News and Gallup found between 20% and 25% of Americans calling themselves fans of professional soccer. Pew, tracking interest in the World Cup, has found those “very” or “fairly” closely watching either the men’s or women’s tournament to have risen as high as 44% (in 1999), but never having dipped below 23% (in 2006). Taken together, one can estimate the sport’s potential following as somewhere between one-fifth and one-fourth of the adult population—nowhere close to NFL or college gridiron levels, but hardly on the fringes.

In the national narrative, soccer seems to be constantly veering between calamity and ascendance.

The familiar spin, even from the pollsters themselves, is framed through exceptionalist thinking (see, for instance, the findings of this Pew poll headlined “Americans to Rest of World: Soccer Not Really Our Thing”). There is a double standard in practice here. If trends as stable as American interest in soccer were found in other facets of American opinion, analysts would be inclined to describe them as values: consistent beliefs and practices that persist regardless of blowing economic or political winds. What dominates instead is the exceptionalist-infused narrative, which fixates on whether soccer is ever going to make it, “get over the hurdle” and become the national obsession it alleges to be around the world. This, in part, is how American soccer’s popular image has come to be framed so heavily in terms of Nielsen ratings and gate receipts: when numbers are up, the sport itself is culturally on the rise; when numbers are down, it’s headed for trouble. In the national narrative, soccer seems to be constantly veering between calamity and ascendance. The tone is akin to that which surrounds a presidential election. Yet when the election is over, the presidency itself emerges from the roller coaster ride and becomes a banal fixture in the daily life of government.

Soccer, however, can’t seem to get beyond the ritual campaign debate.

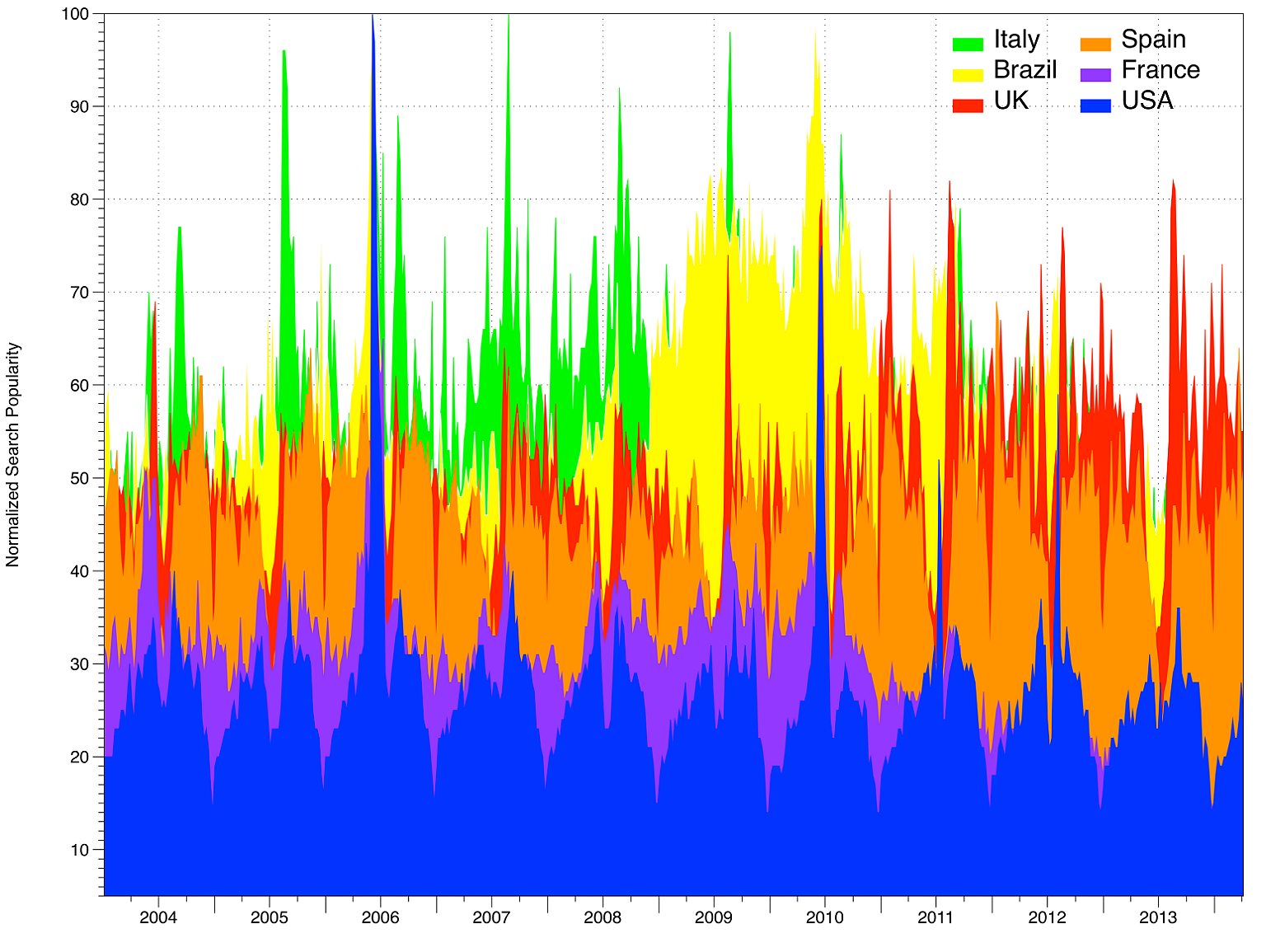

If soccer really isn’t “America’s thing,” to what extent does it hold sway elsewhere? There are at least two ways to determine this. One is to look at similar polls in other countries; the other is to look at Google search terms, across time, to see how frequently individuals around the world are seeking information about the world’s game in their native language.

In the first case, we can consider two similarly-worded survey questions about interest in football from the 1990 Eurobarometer and a 2013 poll by YouGov. What we see is that the game draws interest from majorities of the Italian, Spanish and German publics (59%, 58% and 51%, respectively, in 2013), but in the Netherlands and UK, less than half say they are interested. Moreover, in the latter two cases, the proportions appear to have dropped considerably: among the Dutch, from 64% to 48%, among the British, from 51% to 41%.

But the strongest evidence for the sport’s decline appears in France, where about one third of respondents now claim to be “very” or “somewhat” interested in football compared to half the respondents 23 years prior. The eroding fortunes of le foot are underscored by a L’Ifop report that found interest fluctuating from 31% in 2005 (before losing to Italy in the World Cup final) to 41% in 2008 and back down to 38% when les Bleus were eliminated from Euro 2012. The study makes the point that contemporary French interest, while half of what one finds among Brazilians (where 67% are interested in the game), remains higher than what they find in the U.S.—20%. But the fact that American and French fans would be juxtaposed in the same analysis, given the distinguished history of French football, indicates that changes are afoot.

These international polls tell us two things. First, even in countries that dominate the world game—Brazil, Italy and Germany—anywhere from a third to half of the public remains disinterested in soccer; in the country that invented the organized game, the UK, interest is even lower—and appears to be dropping. This makes the second point the essential one: affinities toward sport can, as appears to be the case in France, fluctuate without raising fundamental questions about the game’s place in domestic culture. Certainly inquiries arise frequently about the future of the sport, as is happening at the professional level in France and the recreational level in the UK, but that is different from debating its very right to exist in a given society. The irony in the American case is that, as this debate continues to unfold (expect to hear variations during and after the World Cup, particularly if the Americans fail to escape from their group) support for soccer has been stable over time. Other indicators, from youth player registrations to MLS attendances, show dramatic long-term growth.

In fact, if web searches are used as an indicator of interest, French and American soccer may be moving in the opposite direction. Reaching back to 2003, Google Trends offers the opportunity to examine the relative rank of soccer as a search term in the United States to football in the UK and France, futebol in Brazil, and calcio in Italy. When the data are plotted as linear functions, one sees trendlines similar to those found in the polls. Italians and Brazilians lead, in terms of football-related searches relevant to total national search volume. UK searches for football are on the rise, in contrast with polls indicating interest in the game is in decline; suggestive, perhaps, of a simultaneous intensification and isolation of the British fan community. In France, however, the trend has been the opposite: searches for football have been on the decline since 2010. All the while, soccer queries among those in the U.S. have held stable. In terms of relative search popularity, Americans, in fact, have more often looked since 2011 on the web for things soccer-related than the French have for things football-related.

Soccer’s steady, if heretofore quiet, emergence into the backdrop of American sporting life returns us to two of the most common pejoratives hurled at the domestic fan: being “isolated” or “elitist.” “Isolated,” by default, because they are detached from the “mainstream” that devotes itself solely to “American” sports. “Elitist,” not simply because of an affinity for an imported product from Western Europe (as well as the players and teams therein), but because of the intersection between American soccer and high society. Think of the New York Cosmos in Studio 54, Becks and Posh in Hollywood, or even a recent article in the New York Times “Fashion and Style” section describing the Premier League as the New York “conversation topic you can’t ignore.”

Reality bites again. Using the General Social Survey (GSS) and The Gallup Poll from 2012, it’s possible tease out the significant social factors that determine whether or not an American is a soccer fan. Five qualities distinguish them:

They’re more likely to be Latino and male; they’re less likely to be older than 50 (similar to hockey fans);they’re more likely to be married and church-going (like NFL/college football and baseball fans); they’re less likely to live in the Midwest or deep South; they’re more likely to be a first-generation American (unlike those who watch baseball or the NFL).

Put another way, neither income nor education have any linear impact on whether an American is a soccer fan. If there is a positive income effect, it is precisely in the middle: at the $30-$75K level.

Moreover, when Americans are compared to their counterpart fans in countries like Australia, Japan and South Korea, they look relatively humble in terms of social class. Throughout Asia, and even in countries as disparate as Finland and Mexico, we see a linkage between higher levels of income and education and watching soccer. In the United States, even when we look only at White non-Hispanics, the linkage doesn’t exist. The stereotypical American, who “supposedly segue[s] from a discussion of Mozart to one on Maradona over cappuccino at the cafe,” is just that: an illusion given life by the pervasiveness of exceptionalist thinking.

The other illusion is that being a fan in the United States is akin to being a Trekkie: taking membership in a subterranean society comprised only of the truly fanatical. Of course, such fans and groups exist – as they do in Western Europe or among the diehards of Major League Baseball or NASCAR. But what is lost in the caricaturing is the fact that, owing to the 20-25% who are consistently interested, there is a sizable casual audience in the U.S., which helps to explain why World Cup television ratings are exponentially higher than those for MLS, Liga MX or the English Premier League.

Understandings of “mainstream” sports fandom often exclude Latinos and immigrants.

What has also been lost, at least until recently, is that Univision, not ESPN or NBC, delivers the most soccer viewers in the United States. According to a report last year by Nielsen, bilingual Hispanics are about as likely to watch the World Cup as watch the Super Bowl and almost equally likely to be fans of El Tri as the NFL. While this may pose a challenge for U.S. Soccer and devotion to U.S. national teams, it reflects the fact that understandings of “mainstream” sports fandom are often facile, excluding Latinos and immigrants as an integral part of American sports culture.

The overlap between futbol and soccer watching exhibited in the Nielsen report makes the broader point: soccer watching in the U.S. is not done in isolation from other sports, but as part of a general sports viewing culture. In both the GSS and the Gallup survey, one finds that soccer fans, irrespective of race or ethnicity, correlate significantly with hockey and basketball fans, while baseball, NFL, and college football fans correlate highly with one another. Hockey and soccer share obvious similarities in terms of the structure and flow to the respective games, as well as strong international influences. While basketball is also aesthetically fluid and widely played outside the U.S., one can surmise that the minority-majority composition of the NBA and some shared values—shaped heavily by generation—may also be at work. Where fans of the NFL, college football and NASCAR have more in common in terms of their attitudes toward immigration and gun rights, American soccer and basketball fans are more likely to call themselves liberals. Soccer fans are less likely to own a gun and favor free trade; basketball fans are more inclined than any other sports fan to support the Democrats.

This, in essence, is what it boils down to: a political conflict where answers to the question, “What is American?” fundamentally differ. When Franklin Foer asked at the end of How Soccer Explains the World, “Why do so many Americans feel threatened by the beautiful game?” he dismissed the possibility that conventional politics could be the source of that sense of threat. He had heard anti-soccer jibes from lefties and pro-soccer defenses from righties. This was four years before Obama ran for the presidency when the political landscape would turn, almost entirely, on the notion of whether a mixed-race, Hawai’ian-born, Kenyan-fathered, pro-government liberal who spent a part of his childhood kicking a ball in Indonesia and eschewed flag pins on his suit-jacket lapels was patriotic enough to hold the country’s highest office. With his triumph came not only a greater place for the game in the White House—MLS Champions are now received in a Rose Garden ceremony like the title winners in other major sports—but renewed worries about America’s power, status and place in the world.

At Obama’s recent speech at West Point, he said he believes in American exceptionalism “with every fiber of [his] being”.

It’s a reminder that a battle over the qualities that define domestic culture from “the rest” continues. Foer is right that this conflict does not always fall along strict partisan or ideological boundaries, but when it comes to soccer, it predictably raises the binary of “US against the World.”

Chances are that the few who declare that “Americans will never accept soccer” neither know of its origins among Native Americans, its “red-blooded American” roots in the St. Louis Soccer League in the 1900s, the 1-0 defeat of England in the 1950 World Cup, or of efforts since the 1960s by Christian oil billionaires to build the sport. Nor do they appear to recognize that their arguments sound exactly like those of some Australians. Soccer’s American critics also seem willfully blind to the sport’s popularity amongst Latinos, suggesting that they don’t think of Latinos as properly “American.” That is how exceptionalism tends to work.

In much of American sports discourse, exceptionalist thinking remains trenchant.

In political discourse, there are signs that this binary is reaching a tipping point, with books and articles from the left, center and right declaring it to be in its last throes.

In much of American sports discourse, however, exceptionalist thinking remains trenchant. It is used to reassert pride in identity and to draw attention to weakness and deviance. It is precisely that mixture of arrogance and exclusion that has defined the “anti-soccer lobby” in the U.S. over the years—a loosely-tethered, but influential, collection of large-city newspaper journalists and broadcast personalities whose careers have been immersed entirely in their own domesticity.

As such writers and commentators are fond of speaking on behalf of “Americans,” compelled to define what is and is not part of “our culture,” their nationalism tends to rise at critical moments, and is projected onto the public as a whole, much as a boisterous populist claims at his party’s convention to speak for the “heart and soul of America.” That misrepresentation is, in turn, amplified by an international media eager to strengthen its own stereotypes about the United States. That is one of the games that will continue, back and forth, during this World Cup, irrespective of what available data tell us about what the Americans—and others—actually think about the game.

[Header image: “US Soccer Fans” by David Wilson, used under CC BY 2.0]