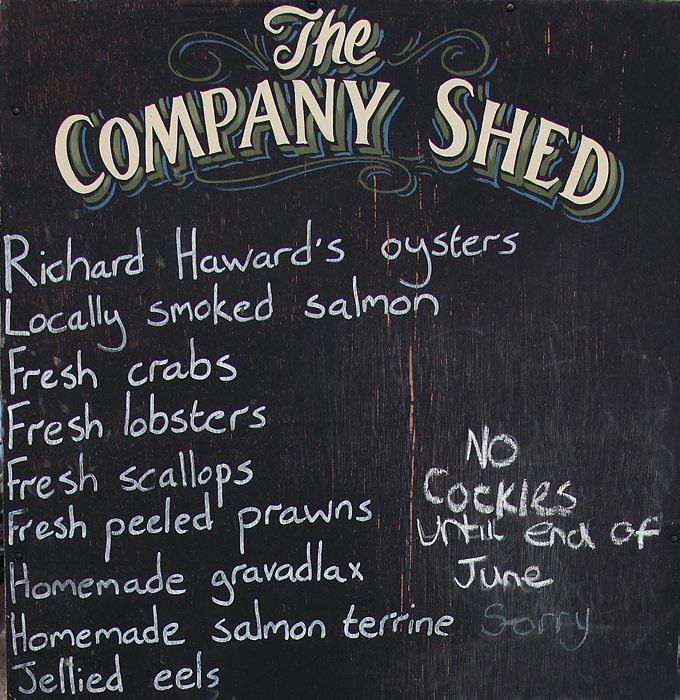

Finding the Company Shed is easy, as long as you read the tide tables before departure. Step one: check that The Strood—the tidal causeway to Mersea Island—isn’t underwater. Step two: drive across it. Step three: stop when the road does. It’s the shed on the left.

Don’t be put off by its appearance. Yes, it’s clad in weatherboards, floored with concrete and sat in a working port on the muddiest coastline in England. But the queue of people spilling out onto the street didn’t come all this way for the comfort, the scenery or the service. They came for the oysters and, if you’ve got any sense, so did you.

In the pub next to my house in London, oysters cost 24 pounds a dozen. An hour and half’s drive away, in the Company Shed, the same oysters are three times cheaper, and many times fresher. They could hardly be fresher, in fact, since the water they came out of is just feet away. The boats that dredged them off the seabed are moored outside, and the man with the white beard who just warned you that your car is getting a ticket, that’s Richard Haward. He owns the place.

His daughter is behind the counter. His son skippered the boat that caught your lunch. He is Mersea’s oyster king, as were six generations of Hawards before him.

In these oozy stretches of eastern England, the sea and the land merge. In the half-light of the early morning, the water appears a liquid version of the earth it washes up against, and the land in turn seems more fluid than it has any right to be. Even when the sun shines, the sea does not gleam like it does in other places.

My grandfather, who spent decades in boats on England’s East Coast, first in the Royal Navy and then for fun, had one word for Mersea when I told him I was visiting: “muddy.” Then he thought for a beat or two and added: “good oysters though.”

Hundreds of little streams trickle off the rich agricultural land of Essex, filling up the Rivers Colne and Blackwater, bringing their load of dirt with them onto the mudflats around Mersea Island. Twice a day the tides of the North Sea wash that silt back and forth, and the oysters lie there under the surface gobbling it up, growing plump and salty and delicious. And they have been doing it for millennia.

Some people in these parts say that it was oysters that lured Julius Caesar across the sea from Gaul. That may not be entirely true, but the first capital of the province of Britannia was Colchester, just up the Colne from here, and archaeologists find an uncountable profusion of oyster shells in any Roman site they excavate. At the legionary camp of Caister-on-Sea, they stopped counting the shells when they got to 10,000.

And these weren’t just military rations. We can date Roman Britain’s first inter-racial couple—he Roman, she British—to just before 61 AD thanks to the oyster shells they were buried with in a grave near Nottingham.

The oysters—Ostrea edulis, officially known as European flat oysters, but round here called “Colchester natives”—were appreciated far and wide. Juvenal, the Roman satirist, summed up the debauchery of his contemporaries by accusing them of “sending to Britain for oysters; not because they had none, or good ones, but merely seeking variety of flavour.”

Considering the logistics that would be involved in keeping oysters alive long enough to get them from Britain to Rome in the first and second centuries AD, we can safely assume he was exaggerating. Nonetheless, it says a lot that the fame of these happy little shellfish had spread all that way.

Oysters in those days lived around the British coasts in untold billions, forming a reef that, like coral reefs in warmer climates, created a whole ecosystem. Fish and crustaceans lived in the crevices between the shells, and everything benefitted from the filtering they did of the water. No matter how many oysters the fishermen dredged up—and they dredged up millions—they could not put a dent in the profusion out there, the wealth submerged just below the low tide mark. Then, something terrible happened.

As the population of London boomed, doubling again and again from the 16th century onwards, these little nuggets of protein became an irresistible way for the fishermen of anywhere within reach of the capital to make a living.

“They’re the most vulnerable marine habitat in the world,” explained Sarah Allison of the Essex Wildlife Trust. “They’re really valuable, and incredibly tasty. They’re a slow-growing, difficult to manage, delicious gold mine”.

In 1864, Londoners ate 700 million oysters: that’s five oysters every week for each man, woman and child in the city.

The oyster boom expanded as industrialisation accelerated, with oysters fuelling industrial Britain’s industrious workers. Modern machinery made them easier to catch, store and transport, and oysters became the signature food of Victorian Britain.

“The poorer a place is, the greater call there seems to be for oysters. Look here, sir; here’s a oyster stall to every half dozen houses. The streets lined with ‘em. Blessed if I don’t think that ven a man’s wery poor, he rushes out of his lodgings and eats oysters in reg’lar desperation,” remarks Sam Weller in Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers.

That was published in 1836, and Londoners were only just getting going. In 1864, they consumed 700 million oysters. That’s five oysters a week, every week, for each man, woman and child in the city.

The same was true elsewhere in Britain, with predictable results. Oyster fishing began to collapse in Scottish waters in the 1870s, and had all but ceased there by 1920. In the 19th century, fishermen discovered a 200 by 70 mile oyster bed on the seabed between England and Germany, and had cleaned it out within decades.

And we have still not learned from our mistakes. In the 1970s, fishermen found oysters in the Solent, the channel between the Isle of Wight and the South Coast, giving hope that the industry could be reborn sustainably, but we ate them all instead.

According to Allison, the UK has lost 99 percent of its native oyster population.

In 2011, England landed a mere million oysters—half a day’s consumption for Dickens’ London. According to Allison, the UK has lost 99 percent of its native oyster population.

That has transformed oysters from a fuel for the poor to a luxury for the rich. As I perched on a pile of tinned food chatting to Haward—there was only one chair in his portacabin office outside the Company Shed—he told me he sent oysters as far as Dubai and Hong Kong. These globetrotting molluscs would laugh in your face if you told them oysters once struggled to make it to Rome.

Marine charts decorated the portacabin’s walls, showing the stretches of river which, by long custom, are his. When his boats dredge up oysters from the open sea, he brings them in and re-lays them in the creeks, leaving them to fatten on the rich silty soup that passes for water along the Essex shore.

If you’re picking over mudflats for oysters, you want to be wearing as much plastic as possible.

Before meeting him, I had gone out with three of his fishermen on a small open boat. It was the twilight before the dawn and, though it was April and supposed to be spring, it was bitterly cold. I was wearing a coat, jumper, t-shirt, vest, gloves and long underwear, but the wind went right through them, so I scrambled in the car for a bag of my wife’s maternity clothes, looking for anything woollen to keep out the chill. And the clothes were not the only problem. When Brian Whiting, Andrew Edwards and Jacek Kolasinski (a Pole, he’s a rare non-local in the oyster business) picked me up in their open boat, they looked in silent disdain at the walking boots I had come in.

“Those won’t do out there,” said Whiting, before trudging off down the jetty, and returning with a pair of bright yellow sea boots. When we disembarked on the far side of the estuary, I was grateful to him. If you’re picking over mudflats for oysters, you want to be wearing as much plastic as possible.

We had to work fast, because the tide comes in quickly. Some say the water can move over the mud as fast as a galloping horse, and that would be bad news for the horse. Even a thoroughbred would struggle to get out of a walk in this dense ooze.

We picked over the stretch marked out by Haward’s withies—long willow poles thrust into the mud to mark his territory—filling up four boxes. Whiting explained, as we sorted the shells, that you could tell the live ones from the dead ones because they don’t rattle when you shake them. I tried but could hear no difference.

“It takes a bit of practice,” he said, with a low chuckle.

Of course, the bars of London and Dubai would need more than four boxes to keep their customers happy that day, and the real fishing is further out to sea. When the sun rose, Haward’s boats would be out dredging the seabed, bringing up oysters in their hundreds.

’The first thing oysters think of doing is dying,’ said Haward. ‘They would die twice if they could.’

But Haward’s job is not just a question of going out there, dredging them up, and counting the money as it pours in. The number of things that will kill oysters before he can even get them onto a boat is improbably huge. They cannot spawn if the water is too cold, and they suffocate if it is too hot. They will be killed by land run-off, by silt, by marine anti-fouling, by untreated sewage, and possibly even by treated sewage if the people whose sewage it is have been taking the contraceptive pill.

“The first thing oysters think of doing is dying,” said Haward. “They would die twice if they could.”

Oysters are technically wild, but have been so messed around by humans over the last few centuries, their reefs smashed up and the individuals scattered, that they are now largely dependent on us. The oystermen have to kill off predators and parasites, keep densities down to control disease, and clear silt off the top of the oyster beds to help them spawn.

But some enemies simply cannot be stopped. Disaster came to the Blackwater in the winter of 1962-3, the third coldest ever recorded in England, when the rivers of Essex froze to the bottom.

“My dad said that in 1962, when I was still at school, just before the winter, there was the biggest stock of natives since World War Two, but the whole area froze solid,” Haward said.

It was a disaster that forced the local fishermen to take dramatic action. They brought in new oyster spat from elsewhere to reseed their beds and support their trade, and kept a tight-knit association to protect their fishing grounds.

“We are oyster growers, we are not fishermen who catch oysters. We take out anything that will harm oysters,” said Haward.

Blackwater Estuary is now one of only a handful of places in England with any native oysters at all.

After decades of dedicated grooming, their stocks are still not back up to the pre-1963 level, but they are at least in existence. Amazing though it seems, the Blackwater Estuary is now one of only a handful of places in England with any native oysters at all.

This is a potentially lucrative position to be in, but a difficult one too. Ownership rights have a habit of dissolving in salt water. Although the fishermen’s claim to their creeks is secure, the common grounds further out are open to anyone.

But four years ago, the fishermen saw a chance to change that, when parliament passed the Marine and Coastal Access Act, giving the government a duty to protect Britain’s seas. If their estuary could be declared a Marine Conservation Zone, then their oysters could be safe from unscrupulous rivals. To have the oysters protected, the oystermen had to have data to prove they needed it. And for that they needed scientists. Luckily enough, they knew whom to call.

It created an almost unique phenomenon in the North Sea: fishermen and environmentalists working together.

In 1999, the Essex Wildlife Trust bought a farm just up the River Blackwater. Keen to restore some of the coastal marshes that have been drained, and keen to experiment with new approaches to protecting the coast from rising sea levels, it decided to breach the dykes and see what happened. The new marshy habitat would undoubtedly suit seabirds, fish and plants, but would it be good news for oysters? Would the pesticides that had built up in the land leach into the river and kill off this jealously guarded population?

It took careful negotiations before the oystermen consented, but it eventually created an almost unique phenomenon in the North Sea: fishermen and environmentalists working together.

“Oystermen will always call themselves conservationists and I agree with that because it takes seven years for oysters to reach a viable size. A seven-year turnover is a long time. A farmer’s turnover is 12 months,” said Allison of the Wildlife Trust. This was late in the afternoon and we were sitting in her first floor office in the farmhouse that functions as the Wildlife Trust’s headquarters. The car park below was full of vehicles. Ornithologists come from all over southern England to see the migratory birdlife the newly created marshland has attracted.

Between seeing Haward and Allison, I had gone out dredging with Haward’s son Bram just off Brightlingsea, a traditional British seaside resort of pastel-covered beach huts, yachts, fish and chips, ice cream vans and mud, on the far side of the Colne. We were working the harbour, a few hundred feet offshore at most, and could spy on the few hardy tourists picking their way along the beach. One girl had a bucket and spade.

While Bram piloted the boat back and forth, the lads worked the levers that lowered the dredge. We then towed it along the bottom, before the hydraulics winched it back up again. The dredge is made of nylon mesh and chainmail, and is about three feet across and a foot high. Its trap door opened to dump dozens of oysters onto a shelf on the transom. Once the oysters were safely onboard, Bram would dump the dredge overboard and resume dredging, while Josh and Sam chipped at the shells with heavy duty tools—half knife, half cleaver—to separate them, before sorting them into boxes in time to start again.

It was hard work and, while they did it, Bram chatted to me about how glad he was not to have to do it himself any more. I asked him how he knew where the oysters were. “Experience,” he said, with a shrug.

It felt a little like sheep farming, if sheep farming were conducted with a giant scoop dangling from a helicopter.

It did indeed seem a curiously random business. Since the water was beige, Bram had no idea whether the dredge would hit an oyster or not. It felt a little like sheep farming, if sheep farming were conducted through heavy cloud cover with a giant scoop dangling from a helicopter.

What the oystermen needed to do to win protection was to systematise this process. They needed to go out onto the open grounds, where the oysters live free and unprotected, and map them. They would have to show the environmentalists their secrets, and possibly risk their entire livelihood.

It would be a treasure map with a giant ‘X’ marking the spot of every hidden cache of shellfish loot.

But finding out how many oysters there are, and where they live, was going to be hard. Allison proved this point by showing me a video she had made while diving offshore. Visibility was somewhere between six inches and a foot. Even when they found an oyster, they had no idea where they were, since they had no way to orientate themselves in the muddy water.

Their plan instead was to dredge methodically from a boat, recording exactly where they found oysters. Such a map, if it leaked out, could allow anyone to hoover up every native oyster down there. It would be a treasure map with a giant letter X marking the spot of every hidden cache of shellfish loot.

“There is nothing to say that someone can’t come in and take the oysters. This report going to government has gone through confidentiality clauses to stop that information getting out,” said Allison, in a spicy Newcastle accent that is just beginning to pick up the broader tones of her adopted Essex.

Together, they scoured the public grounds, using a dredge with far smaller mesh than normal, so they caught the juvenile oysters as well as those big enough to eat, measured them, then threw them back. Every evening, Allison collated her data, typing all these numbers – the length of the oysters in millimetres — into a database to get a sense of what is down there, how many of the little tiddlers below 50mm, and how many ready to be eaten, up above that size.

“You write down all the numbers and you don’t think about what you’re doing because there are hundreds of oysters. But one evening I was working at home and I asked my husband to call the numbers while I typed them out. He said it was like a game of 60s and 70s and that was when I realized it was serious,” she said. Almost every oyster was between 60 and 80mm long. There were no babies.

It was a catastrophe. No one had seen it coming, and no one had any idea why it was happening.

If ordinary fishing continued, the adult oysters would be scooped up, and there would be no new generation to grow up and take their place. This rare healthy population of native oysters was not healthy at all. They told the local fishing authority, which immediately closed all fishing.

As of now, Colchester Natives are off the menu.

“We came across this by accident. We pre-empted a crash by about two years,” said Allison.

So, the fishing beds are closed. Haward and the other oystermen groom the beds, dragging chains behind their boats to try to clear silt off the oysters, but as of now Colchester Natives are off the menu.

So, what was I eating that lunchtime at the Company Shed, and what was Bram dredging off the seabed? Well, among the many pests natives have to deal with is an entirely separate kind of oyster. Worried by the collapse in the 1970s, officials experimented with foreign species, eventually picking on Pacific Rock Oysters—Crassostrea gigas—as an acceptable substitute. At first, these had to be brought in as youngsters, and just fattened up in British waters, but they have rather taken to life here, and escaped from captivity. They are vigorous and are now serious rivals for the role of oyster in British waters. Unlike natives, which have a flat shell slightly like that of a small scallop, these rock oysters are as jagged as their name suggests.

The rock oysters Bram scooped off the bottom of Brightlingsea Harbour had grown in such profusion that they were starting to harm boats coming in and out. Britain harvested five times more rock oysters than natives in 2011, and that ratio is unlikely to come down again any time soon.

And this puts the environmentalists in a tricky position. They want to restore natives, and prevent an invasive species coming in and taking their environmental niche, but they also want to keep the oystermen working so they can afford to keep the natives alive.

“We need to maintain oysters in people’s minds as a food, as an aspirational thing, because that is what props up the industry to do the restoration. We need that or we are knackered,” said Allison.

It’s a tricky compromise to have to make, but really there is only one course open to us as consumers. The task ahead is a tough one but I hope that you are prepared, as I am, to do your bit for the future of this species. You may not like to hear it, but next time you’re anywhere near Essex, you’ll just have to go out to the Company Shed and eat oysters, then go back and do it again. It’s for their own good, after all.