Liverpool star Luis Suárez is Uruguay’s best hope in the World Cup. But he also makes them one of the most despised teams in the tournament.

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay—

I first made it to Montevideo shortly after Richard “Chengue” Morales scored the winning goal against Australia in a World Cup playoff in 2001. Ragged horses and carts danced through the streets like Lipizzaner stallions. Children begging on the streets got extra portions of Pollo Milanese from diners leaving fine restaurants. Beautiful girls shared their grappamiel. And posters of Chengue, a bare-chested Afro-Uruguayan, waving La Celeste (the iconic sky blue Uruguay shirt) were in every shop window. It was a poor, but proud city.

On my second visit in 2007, I saw the remarkable progress of the country under newly elected President Tabaré Vázquez. Under Vázquez all social and economic indices were up. He was the first member of the left wing Frente Amplio to be elected President. Poverty levels plummeted, child hunger was greatly reduced, smoking in public places was banned and Uruguay confronted the crimes committed in the military dictatorship years of 1973 to 1985.

Because this is Uruguay, where soccer is the spiritual infrastructure that holds the country together, there was a soccer element to his rise. Prior to being President of the Republic, Vázquez was President of Club Atlético Progreso, a team with impeccable Anarchist credentials founded in 1917, which later adopted Catalonia’s colors in solidarity with their struggle against fascism. In Uruguay, soccer and politics mix. Though Luis Suarez, Uruguay’s star footballer and one of the keys to the country’s World Cup hopes in Brazil, isn’t outwardly political, he uses Frente Amplio language in interviews when he talks about “social inequality” and “solidarity projects.”

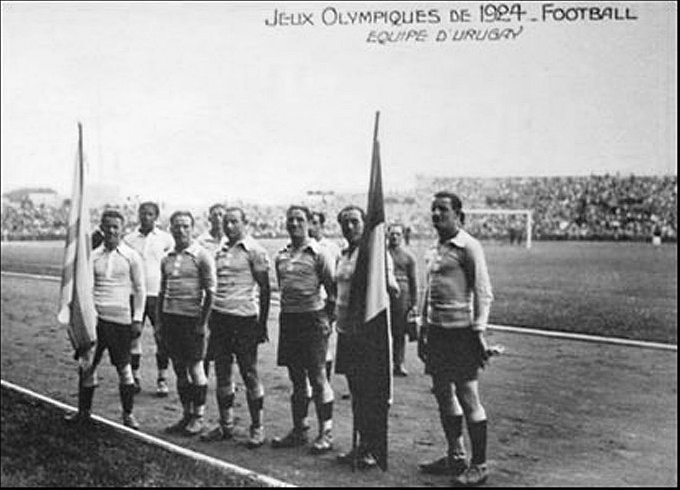

The last time the World Cup was held in Brazil, in 1950, Uruguay were Champions, beating the hosts at the Maracanã. In Brazil, that defeat is known as Maracanaço, and is still mourned as a major national trauma. For their part, Uruguay, who also won the tournament in 1930 (and the FIFA sanctioned Olympic tournaments of 1924 and 1928) remain the smallest nation to have become soccer world champions. They have four stars on their uniform to signify these achievements. Los Charrúas will be back in Brazil for the 2014 Mundial, and although pitted against previous winners England and Italy in the group phase, as well as underrated Costa Rica, they are widely tipped to progress to the knockout round. While Uruguay remains deeply respectful of their opponents, they are also not afraid to entertain the prospect of winning the World Cup. They will also start the tournament as one of the least popular teams among neutral supporters, despite their underdog status and squad containing some of the most dynamic forwards in international soccer.

How is it that Uruguay, a country with a glorious and improbable soccer history, finds itself a soccer outcast synonymous with cheating and bigotry? The answer, justified or not, is Luis Suárez.

A stocky forward with tremendous dribbling ability and a ferocious shot, Suárez was MVP of the 2011 Copa América (South America’s championship), which Uruguay claimed for a record 15th time. For those counting, this is a tournament Brazil have only won on 8 occasions. He is also the most prolific player in the English league today, and plays for Liverpool, England’s most successful club in European competition. A few days before the World Cup draw took place in Salvador, Brazil, Suárez scored four goals in a single game against Norwich City, the third time he scored a hat trick against the team known as the Canaries. The following week he humiliated Tottenham Hotspur in their own stadium, scoring twice and having three assists in a 5-0 demolition that saw the Tottenham coach leave by “mutual consent” (an English euphemism for getting for fired) the next day. On December 20, John W. Henry, the principal Liverpool owner, offered Suárez an improved contract, which made him the highest paid player in Liverpool’s history. The English outside Liverpool fear Suárez because he is gifted and committed. But many also loathe him, because they regard him as a dishonest, violent player and, worse still, a racist.

Suárez’s career in England has been marred by a couple of notorious incidents. In April this year, Suárez sunk his teeth into the arm of his Serbian opponent, Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovic, during a crunch league game. The referee missed the incident and Suárez played on, scoring a 97th minute goal for his ailing team to snatch an unlikely draw. In the media furor that followed, Prime Minister David Cameron took time to make it known how much he deplored Suárez’s actions, and the player was banned for 10 matches.

Suárez had been a pariah for many in Dutch soccer long before he bit Ivanovic. While playing in Holland with Ajax, he had been banned for seven games, also for biting an opposing player. In 2011, he was accused of racially abusing Manchester United’s Dakar-born defender Patrice Evra, the captain of the French national team. An inquiry by the Football Association saw him banned for eight games.

But Suárez’s global infamy rests on an intentional handball in the quarterfinals of the last World Cup. Ghana were aiming to become the first African nation to reach the semi-finals of a World Cup, and at the first ever tournament staged on the continent. In the last minute, Suárez blocked a goal-bound shot on his goal-line with his hand, and was sent off. With the cameras trained on him, standing off the pitch, he celebrated demonstratively when the Ghanaian forward crashed the subsequent penalty against and over the crossbar. Suarez’s was a natural reaction for many football fans, but one that stuck in the craw of many millions more tuning in and hoping to rejoice in an African victory.

Like Uruguay itself, Suárez is more layered and complex than the English (and the rest of the world) would like to believe. What does his treatment say about the deeper history of these nations, and what can we expect in the World Cup when the two teams clash in São Paulo?

There are few lands that the British have not invaded. At the time of writing, I believe only 22 countries have not felt the brunt of a British expeditionary force. Between 1805 and 1807, it was the turn of La Plata Basin (what is now Argentina and Uruguay). On February 3rd, 1807, Montevideo was stormed and occupied by a force of 6,000 British soldiers and sailors. Montevideo was seen as a key to new markets. The occupation lasted a little over six months. Spain had markets too.

This is not the place to analyze the Cisplatine War, but the cessation of this 1820s conflict between Argentina and Brazil (as we know those entities today) led to the Treaty of Montevideo and independence of Uruguay in 1828. The peace was brokered by Britain and it resulted in, as the British envoy observed at the time, “a geographical division of states that benefits England.”

In the century that followed, barons of British commerce made fortunes in Uruguay. And the folk they brought to do the work brought soccer balls. They were English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh, and they joined immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as the descendants of African slaves and what remained of the indigenous Charrúa people and Spanish colonialists to create a intricate brand of soccer that would dominate the first half of 20th Century.

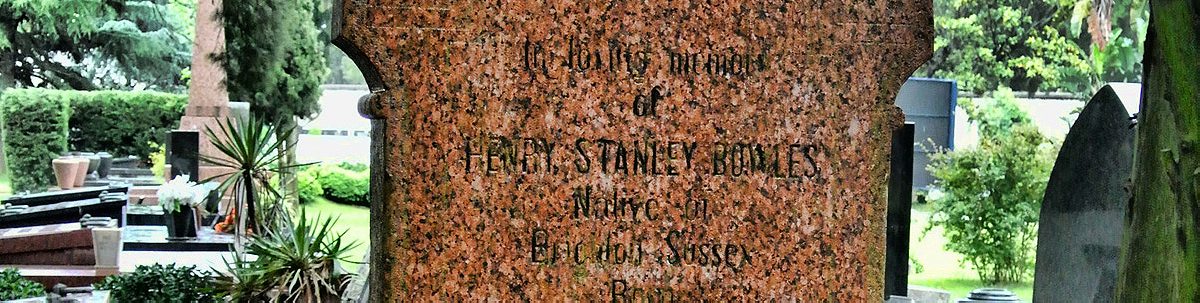

I have a list of places I go to when I visit a city. Highest on this list are iconic soccer stadiums. My first full morning in Montevideo was not, however, spent at the Estadio Centenario—home of the first FIFA World Cup Final—or at the site of what was once the Estadio Pocitos—and which is now partly a lavadero (laudromat) and was where French forward Lucien Laurent scored the first ever goal in a FIFA World Cup tournament, Instead, I went to the British Cemetery in leafy north Montevideo.

Among the barons, generals, and the odd aristocrat or two from old Europe lies the tombstone of an English telegraph worker and soccer player, Henry Stanley Bowles. Bowles, born in 1871, had been a promising apprentice at then powerhouse English club, Preston North End, but transferred to the Eastern Telegraph Company of Montevideo to pursue a career crossing cables over the Atlantic Ocean. Luckily, like all lateral thinking English soccer players of the time, Bowles remembered to bring his soccer cleats.

A few years before Bowles disembarked in Montevideo, the first Uruguayan club soccer match had taken place in 1881 between Montevideo Cricket Club and Montevideo Rowing Club. Bowles’ previous history with the mighty Preston North End did not go unnoticed with the chaps at the MVCC. He was soon on the team. Later, in 1889, a select XI of the best of the Uruguayan club sides was pitted against a team from Buenos Aires. This would be the first international fixture between sides from Argentina and Uruguay. It was Bowles, a man from Sussex, would who score Uruguay’s first international goal and become a Uruguayan legend. (Note: international football had yet to be fully codified–and what counts for Uruguay’s first full international match did not take place until 1901–when the Uruguayan national team turned out in the uniforms of Montevideo’s English-influenced club side, Albion.)

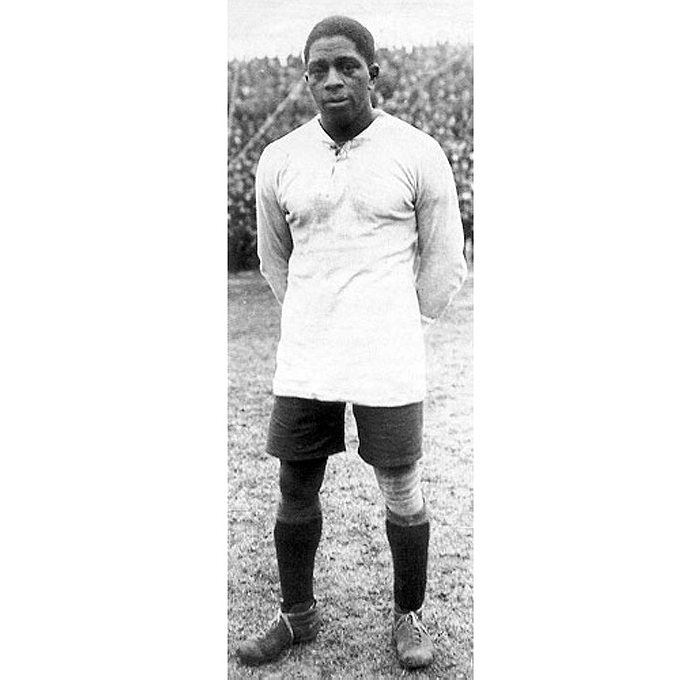

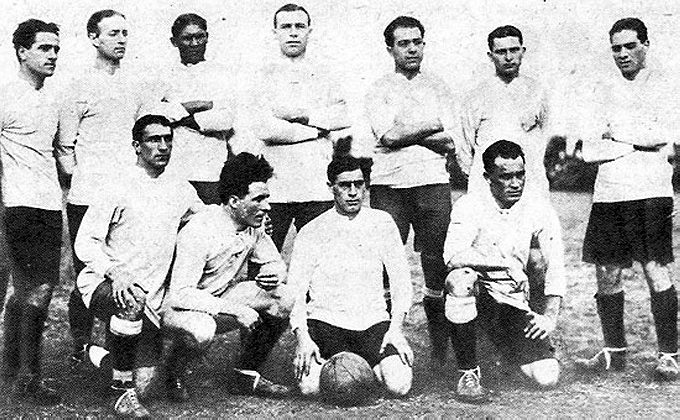

Bowles’ story is emblematic of the English contribution to Uruguayan soccer. Which makes the current vilification in England of Suárez as a racist all the more lamentable. After all, Uruguayan footballers had written the book on how to respond to racism in football nearly 100 years before. As David Goldblatt noted in his tour de force football tome, “The Ball is Round – A Global History of Football”, when 1924 Olympic Champions Uruguay were challenged to a match against Argentina in Buenos Aires, José Andrade, la maravilla negra, or Black Marvel, was pelted with rocks by a racist element in the Argentine crowd. Andrade and the rest of the Uruguayan team responded by throwing the rocks back. In the ensuing melee, the Uruguayans refused to play the game and a member of the Uruguayan team was arrested.

When Suárez was accused of racially abusing Patrice Evra in a Premier League match, a three-man panel at the English Football Association investigated the incident. Suárez was found guilty. The English press pointed to the FA’s 150-page report, approvingly. There was uniform crowing from the English body politic. This was proof England was a football culture and nation that no longer tolerated racism. I would almost agree, were it not for the Jimmy-the-Greek-like comments that continue to pepper the English game. Still, given the relative ambivalence to racist incidents shown by the world governing body, FIFA, and the egregious examples of racism in football that continue across Europe, there is some pride the English can take from their stand.

Despite the appearance of a slam-dunk case—Suárez had, after all, admitted using the term negro in his spat with Evra—there remained questions as to the methodology employed by the English authorities and media. I was particularly surprised at what little interest the UK Media had for the Uruguayan context (for starters: negro isn’t a pejorative in Spanish). Brian Dean, who edits the UK media watchdog site News Frames, had carefully clipped and cataloged the coverage of Suárez’s “crimes” in the English media. “The so-called ‘quality’ newspapers in England,” Dean said, “didn’t seem interested in the aspects of Suarez’s background, which contradicted their own simplistic narrative…. at times the English media exhibited a kind of xenophobia—promoting the notion of ‘ignorant’ foreigners who didn’t have a civilized comprehension of racism. The irony of this seemed to escape them.”

The controversy over Suarez’s alleged racism looks quite different in Uruguay. Barrio Sur and Palermo, two predominantly black neighborhoods in Montevideo, sit adjacent each other in the southern sprawl of the city, on the opposite peninsula from the safe harbor and docks. Penned in by the sea, the streets slope up sharply. Pastel-colored houses are packed tightly, a lick of paint and a buck short of being guidebook material. Random precincts, tower blocks and walls intrude on the harmony. The ‘urban planning’ of the military dictatorship years insulted the neighborhood integrity, but could not diminish the communities.

THE PREVAILING CLAPS WHEN URUGUAY PLAY CAN BE TRACED BACK TO THE BEATS AFRICAN SLAVES USED TO COMMUNICATE ON THE SUGAR PLANTATIONS

Nothing demonstrates the Afro-Uruguayan vitality of these districts like the weekly candombe festival on Sundays. I had first come across candombe in the East Village of New York City, where my passion for Uruguayan football was nurtured in the Uruguayan immigrant community. I often joined Uruguayans in the pastry shops and bars of Queens to watch La Celeste play. But getting to know Uruguayan football also meant making the acquaintance of three large barrel drums or tamboriles—the chico (small rhythm), the repique (medium, improv) and the piano (bass). These characters are what the tailgate is to American football or what the rattle was to the English game. Indeed, the prevailing claps at the Estadio Centenario when Uruguay play can be traced back to the beats African slaves used to communicate on the sugar plantations.

In Barrio Sur, I asked Victor Ribeiro, a musician, what the black contribution to Uruguayan soccer meant to him. El Negro Victor as he insisted on being called, told me, “While Uruguay is a land of much immigration, it is astounding what is most representative of Uruguay. It is music and football–both of which have been largely influenced by its black people.” And what about Suárez, I asked. “Is he a racist?” Victor laughed and responded, “Not at all. Even Pepe (Uruguayan President José Mujica) came out to support Suárez.” I also asked Victor if he had one thing to say to Luis Suárez, what would it be? Victor’s response: “Vamo arriba negro”, a term he told me was a common expression of encouragement.

I asked another Afro-Uruguayan resident, William Lima, if he thought Suárez was racist. “No, not at all. Cultures are different. The Uruguayans consider this different. For us, what Suárez and Evra said was football stuff. I support Suárez as a Uruguayan. To Evra, I say, ‘let’s play football and leave the silly things.’” Did he have a message for Suarez? “You are great player,” said Lima, “but sometimes you have to shut up and play football.”

The use of the Spanish word negro, despite the UK media’s outrage, does nothing to tip Suárez as racist or not racist. But although Uruguay is no more immune from chauvinism and racism then other countries, there is still a deep and unfortunate irony in the animosity with which Uruguay will be received in this World Cup.

The quarterfinal handball in Soccer City, Soweto, remains a vivid and indelible indictment of Suárez and Uruguay for most neutrals, but for Uruguayans it marks a continuum of their tenacity in World Cup play.

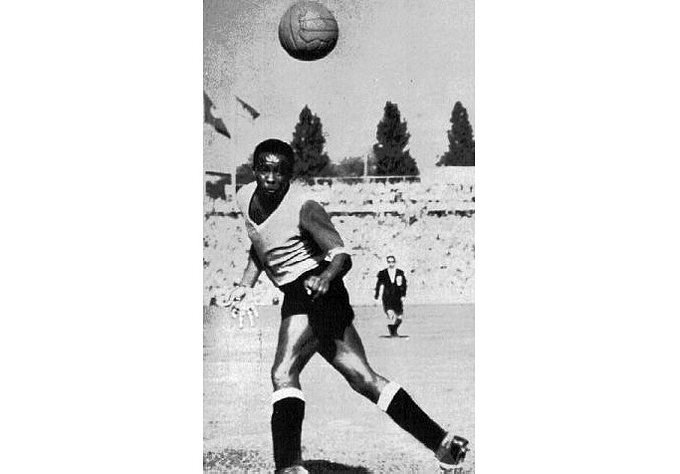

Take, for example, the moment in the very first FIFA World Cup final in Montevideo in 1930 that for me most typifies Uruguayan football. It was not a spectacular goal or a controversial handball, but a game-changing block. The second half score was 2-2. Argentina broke into Uruguay’s box with a man advantage. Blown coverage. An Argentine forward lined up to shoot. It would have been an historic goal, but for Uruguay’s José Andrade. The midfield man came steaming back across the area like a runaway train and slammed into the shot. For me, this remains the most compelling action of any World Cup final. I have watched the grainy footage time and again and still can’t believe Andrade made the play. Argentina secured a corner, but they had been smashed into a million pieces. This interception was classic garra Charrúa–a term Uruguayans invoke when finding themselves competing against invaders, or in a modern context, in sporting competition. In essence, it means victory in the face of certain defeat. It signaled a famous 4-2 triumph for Uruguay.

Andrade was not the first black Uruguayan to have a seismic impact on world football. Isabelino Gradín and Juan Delgado contributed to making Uruguay the perennial champions of South America a generation before. Gradín was the leading scorer in the first Copa America (South America’s football championship) won by Uruguay in 1916. This achievement was three decades before Jackie Robinson started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers and six decades before right back, Viv Anderson, became the first black footballer to play for England. José Andrade’s nephew’s Víctor Rodríguez Andrade also played his part in Uruguayan football lore in the 1950 tournament—alongside El Negro Jefe (Black Boss), the nickname of the legendary Uruguayan Captain Obdulio Varela—who lifted the Jules Rimet trophy (the original World Cup) in Brazil’s backyard.

Suárez will remain a miscreant for many outside Montevideo, forever tainted by a handball, the two on-field bites and particularly the accusation of racism. For Uruguayans, Suárez conjures up memories of the ancestors like José Andrade and Obdulio Varela; he is committed to the same Charrúan cause they were. It is this history and tradition that England, Brazil and others must fear in the next World Cup. Luis Suárez will not be playing for himself, but for his team, his people and those who came before him.

Additional Reporting and Translation by Cecilia Nan

[This article was amended to clarify Luis Suárez’s relationship to the Frente Amplio political movement]

[Header image by: AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico]