Eight generations of Louisvillians have led Michael Lindenberger to this week, this bar, this bourbon. Why not join him?

When the editors of the brand new Sports Illustrated cobbled together the money to pay William Faulkner to come to Louisville to write about the mad scene leading up to the 1955 Kentucky Derby, they had but one real concern: How to keep the famously thirsty Southern writer away from the city’s equally well known, and forgiving, attitude toward bourbon drinking long enough to keep him writing. They needn’t have worried. Faulkner was on a roll. On the day he arrived, Tuesday of Derby Week, he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and by the end of the week had produced, in daily chunks of 300 words each, one of the most famous pieces of sports journalism of the last century.

I am not going to promise that you will have that same kind of luck this week should you decide to join me in Louisville for the horserace, which will go off again on Saturday in front of 165,000 or so whiskey-drunk gamblers and maybe 15 million Americans watching from the safety of their living rooms. But as the Lotto hucksters keep telling us, you can’t win if you don’t play – and there’s never been a better place to be on the first Saturday of May than in Louisville, Ky., when the bugler calls the horses to post and the lonesome notes of Stephen Foster’s My Old Kentucky Home wash over the more or less awe-struck, already hopped-up crowd beneath the white twinned spires of Churchill Downs.

By the end of that week in 1955, Faulkner had understood just that. He was, after all, a man who knew something about the power of place, of history—and of that brown liquor called bourbon that snakes through the story of Louisville like the muddy river on whose banks it was founded.

The race was already old in 1955, having been run year after year since 10 years after the slaves were freed, long enough then to count as a permanent fixture on the spring social calendar in all the right places in the South, but not yet so venerable a fact of life that very old folks couldn’t remember a time without a Derby.

But that didn’t limit Faulkner’s imagination.

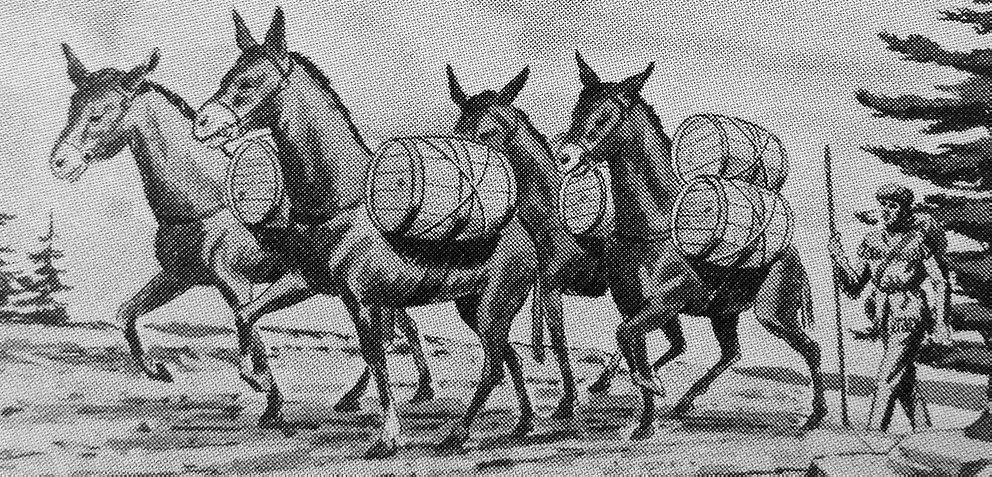

“This saw Boone:” the piece began, “the bluegrass, the virgin land rolling westward wave by dense wave from the Allegheny gaps, unmarked then, teeming with deer and buffalo about the salt licks and the limestone springs whose water in time would make the fine bourbon whiskey; and the wild men too—the red men and the white ones too who had to be a little wild also to endure and survive and so mark the wilderness with the proofs of their tough survival—Boonesborough, Owenstown, Harrod’s and Harbuck’s Stations; Kentucky: the dark and bloody ground.”

Which was fine, as far as it went, but by focusing so hard on the Kentucky aspect of the race, he missed something important—something maybe no son of Mississippi could have seen.

The Kentucky Derby may be named after the state in which it runs, and where most of the nation’s fastest thoroughbreds are still sired, where 95 percent of all the bourbon in the world is made, but the first thing to understand about the Kentucky Derby is that it belongs entirely, from hoof to harness, to the city of Louisville, the city where I was born and where my father’s forefathers, eight generations back, helped settle two hundred and thirty five years ago this month.

It’s the one time of the year that Louisville acknowledges the inarguable fact that it is located in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which means, like it or not and many don’t, Louisville is in the South.

But hell, cultural loyalties can be confusing. All you need to understand about the race that’s going to happen on Saturday is that the real experience of the Derby has everything to do with the place where it happens—and that place is a city, maybe Kentucky’s only city. And it’s a place with its own dark and bloody history.

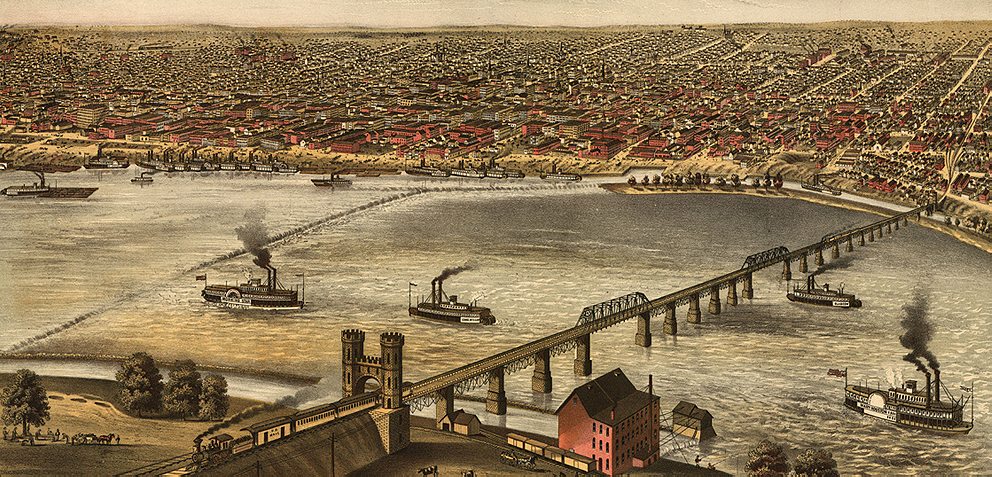

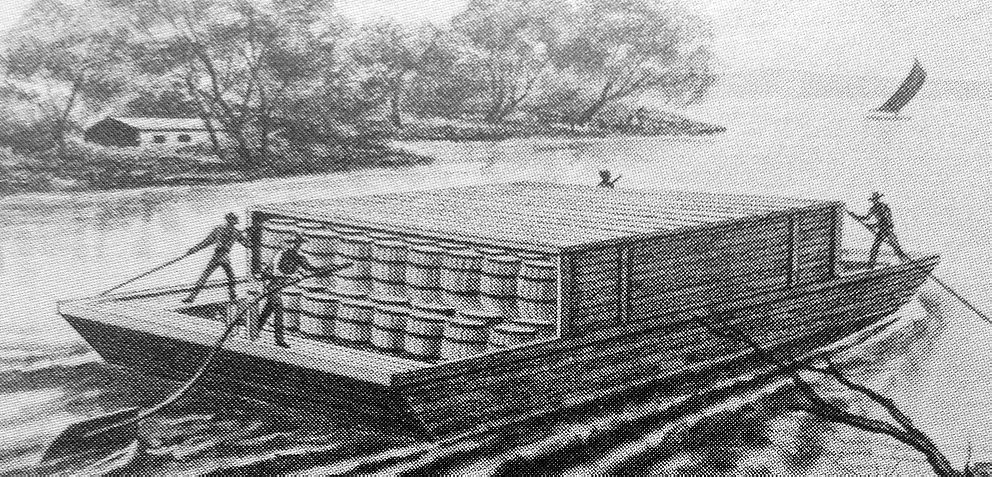

The Ohio River stretches nearly 1,000 miles from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois—and if you stepped onto a boat at its mouth and floated downward, you wouldn’t stop for 600 miles. “The Ohio is the most beautiful river on earth,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in his Notes on the State of Virginia. “Its current gentle, waters clear, and bosom smooth and unbroken by rocks and rapids, a single instance only excepted.”

It was at that singular instance that settlers of Louisville stopped in May of 1778. They were 20 or fewer families, tagging along behind a solider and whiskey drinker named George Rodgers Clark who was on a secret mission for Gov. Patrick Henry of Virginia. Clark’s purpose was to establish a fort at the Falls and from there raise men to push westward in the hopes of extending young America’s boundaries by the time peace would be negotiated with Great Britain.

He had allowed the families to come along reluctantly, but soon realized their value in obscuring the military nature of his expedition. Clark’s victories the next year at Vincennes and elsewhere would be credited for a peace treaty with Britain that included the whole of the Northwest Territories.

My father’s great-great-great-great grandfather was one of the soldiers Clark left behind to guard the settlers when he pushed westward. Within a couple of years, Capt. James Patten was an original trustee of the town of Louisville and would go on to build Louisville’s first stone house, a two-story affair with a view of the Falls and a kitchen built right into the trunk of a still-living and gigantic oak. After the Revolutionary War, and when Kentucky became a state in 1792, he was named the first—and for years the only—riverboat pilot on the Falls licensed by the Kentucky legislature.

In 1782, my ancestor sold 660 acres to distiller Marsham Beshears. A deed recorded the the price: 165 gallons of whiskey

But back in May, 1778 there was no town at the falls—only a tiny island set a long stone’s throw from the densely forested southern shore. Worried about Shawnee warriors, Clark ordered the settlers to build a temporary camp on the island, which stretched just five hundred yards across and what would be less than ten city blocks long.

The families cleared trees on the little island and soon had their first crop of corn rising out of the mud, and the settlement had a new name: Corn Island.

Corn, of course, is the main ingredient in the whiskey that Louisville’s finest and others in Kentucky would soon get busy distilling. In 1782, my ancestor James Patten and another man sold a tract of 660 acres to Marsham Beshears, a fellow member of the town board of trustees. A deed recorded the purchase, and the price, too: 165 gallons of whiskey.

Whether Beshears is the first commercial distiller in the city is a matter of debate. Most accounts suggest that honor should go to Evan Williams, another town trustee, who opened and operated a still at the foot of Fifth Street beginning in 1783, quickly earning a reputation as a man whose whiskey was strong proof against the winter chill.

Williams was later indicted for selling whiskey without a license and his distillery declared a nuisance on account of the foul runoff it produced, but clearly the whiskey habit had taken hold: By 1810, government records would show that some 2,000 stills were operating in Kentucky. And you can still buy Evan Williams bourbon by the bottle.

It would be another six and a half decades before the grandson of Clark’s younger brother William—the explorer who launched an expedition to the Pacific from Louisville with Meriwether Lewis in 1803—would create the Derby, but by then the brown liquor was already coursing through the intertwined histories of Louisville, of Kentucky and, later, of the Kentucky Derby, like a river all its own.

It was the mighty Ohio that gave Louisville its first purpose and which still lends it a beauty that landlocked cities must envy. The Iroquois called it Oyo, which means the great river, and the Frenchman René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, one of the first Europeans to see it, recorded it on his 1669 map as, simply, ‘la Belle Riviere,” or the beautiful river.

Slaves and abolitionists would come to know it by another name, however: the River Jordan, in a nod to the freedom that lay just on the other side from Louisville.

Any discussion of Derby City has to acknowledge that it’s a place that generations of slaves sought to slip past, to avoid at all costs, to flee from. If they were caught, whether at the river or deep in the north, they were often dragged back in chains and sold at auction on street-corners in downtown Louisville. Kentucky may have sided with the Union, but it was a slave state. As my family was in this town from the beginning, slavery was part of their story too. Last year, deep in the archives at the massive genealogical library maintained by the Mormons in Salt Lake City, I discovered the 1810 Census form for Capt. Patten. There, in faded black marks, was incontestable proof that five years before he died in the house overlooking the Falls of the Ohio, he was a slave owner. Among the oldest legal records in Louisville is a death sentence recorded for a slave named Tom, for the crime of stealing less than three yards of fine Cambric linen from that same ancestor of mine, Patten.

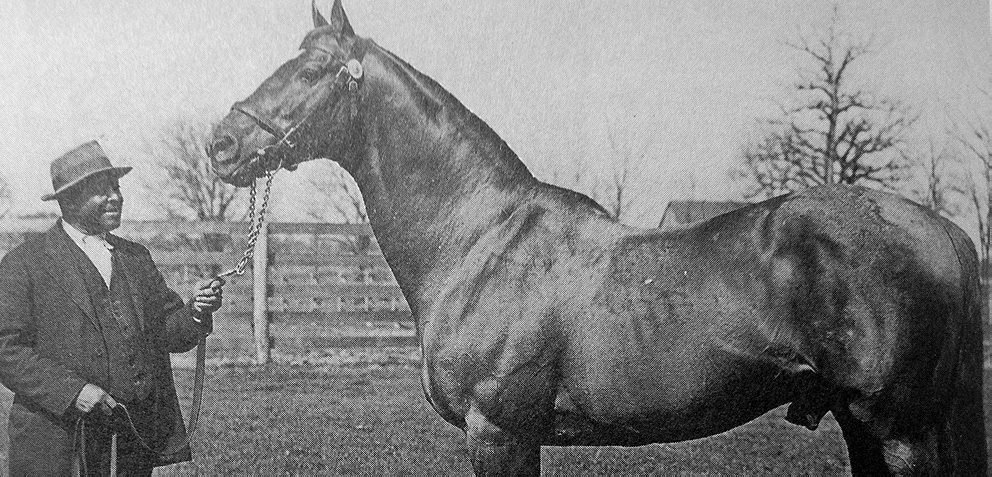

Those things aren’t easy to learn, and harder yet to square on a week like Derby week, where Louisville tries to turn its traditions into an unalloyed, glorious good time. But blacks have been part of the Derby from the beginning, sometimes in unexpected ways. When Meriwether Lewis Clark’s year-old track hosted the first Kentucky Derby in 1875, in front of some 10,000 fans, thirteen of 14 starters in the Derby were ridden by black jockeys, including the winning rider aboard Aristides. Black jockeys won many of the first 25 Derbies, but have long since dropped out. There hasn’t been a black winner since 1902.

For 15 years, Chicago filmmaker Barbara Allen traveled to Louisville to meet friends from all over the world and party the weekend of the Derby. Her memories of the city and the race remain fond, she told me, three years after she was here last. “I still love the Derby.”

But she also recalled that faces like hers, black faces, were rare at the white parties that so define the public image of Louisville during Derby Week—at least they were rare among the guests.

“There seems to be two Derby celebrations: One white, where the blacks work and pick up extra cash catering,” she said. “And another, distinctly black, with family gatherings and reunions, neighborhood parties and clubs open all night. Unfortunately, the black parties always got harassed by the police, but we’d have a good time anyway.”

Muhammad Ali bent forward and I leaned in to hear. “This isn’t my home,” he said

Many black voices in Louisville say the harassment, or at least heavy watchfulness, of the police has remained a fixture over Derby weekend. In 2006, the then-mayor Louisville announced that the city would no longer permit ‘cruising’ on Broadway, the main east-west drag downtown. The year before someone had been shot, and 400 police had since been assigned to monitor the impromptu gatherings that took place along West Broadway in historically black west Louisville.

In recent years, with the cruising officially banned, police by the hundreds monitor the west Louisville’s main drags throughout Derby weekend. With tens of thousands of mostly white residents crowded bars all over the rest of town, that has left some sour taste for some in the west end.

Still, the parties continue in other ways. Families gather by the hundreds in Shawnee Park and elsewhere to party on Derby Day, and there doesn’t seem to be any less fun even if the menu has fried bologna instead of the garlic-crusted prime rib with Henry Baines sauce served by the uniformed waiters on the fourth- and sixth-floor seats known as Millionaire’s Row at Churchill Downs.

It raises the question of whether the Derby truly belongs to all Louisvillians. A story: Years ago, I was on assignment for Reuters, prowling Millionaire’s Row in between races. In walked Muhammad Ali, shuffling slowly across the room.

He might as well have been walking on water, for all I cared. He has always been, and always will be, the first citizen of the city of Louisville, even if some few of its older residents have never stopped seeing him as a draft dodger.

I approached Ali gingerly, his face a mask. “Welcome home, champ,” I said. “How does it feel to be back home?”

He bent forward and I leaned in to hear. “This isn’t my home,” he said in a barely audible whisper.

The words startled me and I looked up at his face. His expression never changed and in a moment he was shuffling by.

I’ve thought about that ever since, and wondered what he really meant. I still wonder, but it’s hard to say. Legend says he tossed his gold medal from Rome into the same river James Patten used to trawl as a pilot. But then, Ali has never stopped bragging about Louisville, either, and images of him showing off the pink Cadillac he bought his parents the day he turned pro aren’t easy to forget. He bought the car with the $10,000 signing bonus he received from the syndicate of 11 wealthy, white businessmen, led incidentally by an executive of the Brown Forman distillery.

Ali bought a home in Louisville in 2007 and talked about moving back for a while. He still might.

And this year, against all hope, one of the leading contenders for the Derby is a horse named Goldencents that will be ridden by Kevin Krigger, a 110-pound jockey who is the first black rider in the Derby since 2000.

How much of this history, the new stuff or the old, will be known to the mint julep drinkers who will be betting close to $200 million this Saturday is anyone’s guess, but the smart money says not much.

That they will still be standing by then, some of them anyway, will be testament enough to the tough frontier stock from which Louisvillians are made of.

It’s always been a mad scene. In 1970, the race was 95 years old, and Hunter S. Thompson was 32. It had been 14 years since he had been released from a Louisville jail on condition that he leave for the Air Force immediately, and he hadn’t been back to a Derby for a decade. And yet, as he wrote in his seminal piece for Scanlan’s Monthly, The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved, looking out onto the stands from the press box on the day before the Derby, he had a pretty good idea of what to expect the next day. Standing next to Ralph Steadman he pointed to the Infield.

“I pointed to the huge grassy meadow enclosed by the track. ‘That whole thing,’ I said, ‘will be jammed with people; fifty thousand or so, and most of them staggering drunk. It’s a fantastic scene–thousands of people fainting, crying, copulating, trampling each other and fighting with broken whiskey bottles. We’ll have to spend some time out there, but it’s hard to move around, too many bodies.”

“Is it safe out there?” Will we ever come back?”

“Sure,” I said. “We’ll just have to be careful not to step on anybody’s stomach and start a fight.” I shrugged. “Hell, this clubhouse scene right below us will be almost as bad as the infield. Thousands of raving, stumbling drunks, getting angrier and angrier as they lose more and more money. By midafternoon they’ll be guzzling mint juleps with both hands and vomiting on each other between races. The whole place will be jammed with bodies, shoulder to shoulder. It’s hard to move around. The aisles will be slick with vomit; people falling down and grabbing at your legs to keep from being stomped. Drunks pissing on themselves in the betting lines. Dropping handfuls of money and fighting to stoop over and pick it up.”

Thousands of raving, stumbling drunks, getting angrier as they lose more and more money. —Hunter S. Thompson

If that sounds over the top, maybe it is—a little. Like much of Thompson’s most imaginative journalism, when it comes to the Derby it can be hard to draw the line between fantasy and reality, even by people who have lived it.

Take my friend Kevin Hyde’s recollection. He’s a writer and a stay-at-home dad and a drinker. He isn’t entirely sure where the line between Derby myth and Derby fact is drawn. He blames it on the whiskey, of course.

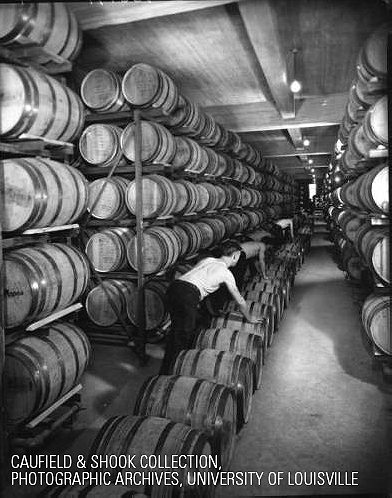

“I grew up in an east side Louisville suburb, which looked like it was pulled right out of a late-1970s, early-80s Spielberg movie,” he told me last week. “There was a middle-aged woman who lived down the street from us–a doctor, an MD, as I recall. Every once and awhile, as we ran and played throughout the neighborhood, my friends and I would see her in her backyard, slowly rolling a large wooden barrel back and forth.

“It turns out that every spring she procured a used bourbon barrel from her brother, who worked at Brown-Forman. She would splash about a gallon of water into the bottom and close it up. Throughout the summer, she periodically rolled it, thus pulling the alcohol from the wood and producing a nice, little 40-proof batch of pure Kentucky brown wine. “I don’t need to add water,” she once told my dad. “I just pour it over ice.”

“Now, this might be a childhood memory severely altered and romanticized by years of bourbon drinking. But I swear I remember seeing her once, in full Kentucky Derby regalia–the beautiful spring dress, the hat, the whole thing–holding a drink and kicking that big, damn barrel back and forth in her yard.”

He added: “If it didn’t happen, it should have.”

This was Louisville. This was Derby. This is why they invented bourbon

There’s a kind of hazy allure about the Derby for those who have lived it year after year after year that makes those kinds of recollections seem entirely normal in Louisville.

Allen Helm, a microbiologist on staff at the University of Chicago, remembers Derby Week in 1997, the last year before he left town for good to pursue his doctoral studies.

“I was the first person in my family to get a bachelor’s degree,” he told me. “Up until then, everybody got out of high school and immediately went to work or hit a junior college. Nobody left town… in fact, most everyone lived within a few miles of each other… a tight-knit, German Catholic family.”

He made sure, then, that he would do his last Derby week the right way. He spent much of it in bars, in particular a restaurant called Come Back Inn, where they poured his favorite brand, Wild Turkey. It was a sunny afternoon on Thursday, and the annual Derby Parade was just about to start. In through the door streamed a bunch of local writers and others ready to talk about the city, its politics, culture and music. He was in heaven.

“We hung out for about an hour, they with their Woodford Reserve, and me with my Turkey… each drink over rocks if I remember correctly. I remember the frosty glasses catching the sun coming through the large windows at the entrance of the bar.”

The others left for the parade, and Helm stayed inside. “I stuck around to watch the parade on TV, over yet another Wild Turkey. I drank it in pretty deeply. This was Louisville. This was Derby. This is why they invented bourbon.”

There are more people who feel that way in Louisville than is easy to explain, even with a Ph.D.

And then there are others, of course, who stay away from the madness altogether, who see the whole season as a great time to go on vacation. Or some just remain and shut out the madness like the groundskeepers on some beastly old manor in the English countryside on the one day of the year when the locals are allowed to traipse through the gardens and have a picnic.

Take Kevin Morrice, another writer from Louisville, who now lives in England. “I’m a native Louisvillian from the school of thought that the Derby is for out-of-towners,” she explained, though she couldn’t help but admit that this time of year she gets homesick for the balloons, the flowers and the parties. “I’d like to come back and maybe get young Charlie (her 12-year-old son) hooked on all of it.”

But then, my father is 84 and except for a brief stay in Chattanooga during the Great Depression, he’s never lived anywhere but Louisville – and hasn’t attended a Derby and wouldn’t if the governor asked him to sit right next to him. He’s typical of a very different kind of Louisvillian than the ones I know best: He’s someone who would no sooner exchange his daily beer and glass of wine—one of each, please—for a bottle of bourbon than he would switch his Marlboros for marijuana, which is to say it’s never going to happen.

You’ll find me having lunches—more than one, when I can, like a hobbit and his breakfasts

It’s Wednesday of Derby Week and that means you’re already late for the party. What you missed: Fully half-a-million locals crammed on the banks of the Ohio River watching fireworks two weekends ago, the official start of the Derby Festival. Also: Runners snaking through the city on a marathon last Saturday, a hot-air balloon race, and nightly drinking and music festivals that used to be known as Chow Wagons but now just mean food, drinks and music at sites scattered throughout the city.

If you get here today, right now, you might see the Great Steamboat Race, easily the most crooked competition in the history of sporting spectacle, that nonetheless will bring thousands of drinkers to the banks of the river to watch the Belle of Louisville steam boat race up the river and back again, usually against a rival boat from Cincinnati.

Tomorrow: The annual Derby Parade in downtown Louisville, which means floats and bands and yet another excuse for Louisvillians to cut work early and drink in the afternoon.

In fact, that’s pretty much what has been happening all week: Long lunches, multiple drinks and nervous scanning of the racing forums as everyone asks, “Have you got your horse yet?” Few do, so soon, and those that have used some combination of gut instinct, folk lore and intelligence overheard in the men’s room and picked a winner keep it entirely to themselves.

No matter where you go this week, it will be crowded. Although the winters in Louisville are often mild, Derby Week is seen by nearly everyone—everyone besides my dad, perhaps—as an excuse to get out and stay out much later than anyone with any sense would suggest.

The other part of all this is the food. It’s probably better than the food in your city, unless you call New Orleans or New York or San Francisco home. And it’s better than usual, come Derby Week.

If you’re meeting me this week in Louisville, you’ll find me having lunches—more than one, when I can, like a hobbit and his breakfasts— and that means you’ll find me happy. You may find me in the West End, a large area of town that is largely black and largely poor. It’s also close to the river and often beautiful. And best of all, there’s Big Momma’s Soul Food Kitchen near 45th Street and Broadway, where if you don’t mind standing in line at a shack not much bigger than a taco truck, you’ll leave with a pile of fried chicken, pork chops—smothered chops on Fridays—collard greens, green beans and everything else that’s good.

If you’ve remembered to bring a clean shirt, you might meet me at Jack Fry’s for lamb chops and Manhattans—but not if you haven’t made reservations months ago. After dinner at Jack Fry’s, take a cab or clear your head with a walk over to the newly lively area east of downtown called—with it must be admitted a tremendous lack of imagination—NuLu. You might find me amid the art galleries and hipster coffee joints for a game of outdoor ping pong at the Garage Bar, owned by a whiskey heiress. Or I might be down the street still further at Meat, a cocktail lounge in Butchertown situated on top of the Blind Pig, where the meat is good.

Or maybe everyone will be sitting in the Oak Room at the same old fancy Seelbach Hotel where Scott Fitzgerald used to lunch and rub shoulders with some of the biggest gangsters in the Midwest, and where he’d later stage Tom and Daisy Buchanan’s wedding reception in The Great Gatsby.

But it’s the bourbon, not the food, that Louisville does better than anywhere else on the planet.

If you don’t believe me, ask Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer.

He keeps a bourbon library that would make Jay Gatsby green. “In the first week or so of being the mayor,” he said, “one of the distilleries sent me a bottle of their bourbon and I put it in the office. Within about two weeks of being mayor, I think I had a bottle out of every distillery around. Now, I joke that we have the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, the Urban Bourbon Trail (in the city) and a third option we call: My office.”

The advantages of office don’t stop there. “You know this is one of the best perks of being mayor, every year at Derby. I mean I can just get in the car and they will drive me right down Fourth Street right up the gates and I can get out and walk right into the Kentucky Derby. That’s pretty good.”

Gov. Beshear spoke slowly to me, as if to a child. “You can’t be governor of Kentucky if you don’t drink bourbon,” he said

But the unelected and unanointed have plenty of places to drink as well in Louisville. At Jack’s Lounge in the east end, the co-author of the exquisite Kentucky Bourbon Cocktail Book tends bar, as she has for a generation, and if she can’t teach you the difference between bourbon and rye then you really ought to be in Lansing, not Louisville, this week.

Slip into Bourbons Bistro along the train tracks in old Crescent Hill, and you’ll be handed a menu with more than 100 bourbons – and you can always ask for the reserve list if that’s not enough.

It’s not just that there’s more places serving bourbon in Louisville than anywhere else. That’s true, but it’s also true that there is just more of the stuff to go around. Bourbon is booming. Last year, for the first time since 1973, Kentucky bourbon distilleries produced a million barrels.

A few months ago, when Makers Mark distillery announced it would water down its bourbon to make it go further and when Louisvillians collectively gasped so loudly that the company backtracked almost within a week, I had called the governor of the state, Steve Beshear, to see where his administration stood with regard to the emergency. Maker’s Mark, he said, had learned something he learned a long time ago in politics: You don’t mess with people’s religion, their families or their bourbon.

I asked him if he was a drinker himself. He paused, and then spoke slowly, as if to a child. “You can’t be governor of Kentucky if you don’t drink bourbon,” he said.

Good point. Last week, I asked the mayor of Louisville if he was a drinker, especially around Derby. Of course, Fisher said. He’s newer to politics than the governor, and he added, sheepishly, “responsibly.”

We can mark that down to the innate caution of a man who just announced he’s seeking a second term, because everyone, including the mayor of Louisville, knows there is nothing especially responsible about restraint during Derby Week.

This is a town, after all, that keeps its bars open till 4 a.m. every day of the year, except Friday and Saturday of Derby Week, when they are open till 6 so everyone can have their fill of whiskey without feeling rushed by the coming dawn.

In fact, the whole week is one big excuse to stop rushing, stop worrying, and to start drinking—or for those who prefer to count their vices one at a time—to at least start gambling.

Really, the only reason to rush this week, is in the getting here. And, since it’s Wednesday of Derby Week already, if you’re not yet in Louisville, you’re late.

[Top image courtesy of R. G. Potter Collection, Photographic Archives, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.