In Catalonia, booming local microbrews are just another way for people to express their independence.

BARCELONA, Spain—

In early 2005, when Àlex Padró opened Barcelona’s first microbrewery, craft beer was hard to find. As Llúpols i Llevats (which means hops and yeast in Catalan) began producing its first carefully wrought bottles, Padró got some quizzical looks. “They said, ‘What are you offering me? This is beer? And so expensive!’” he recalls.

For decades, Spanish beer behemoths such as Estrella Damm, founded in Barcelona in 1876, and Moritz, a recently revived competitor, have dominated the beer market in Catalonia. The mass-produced beers are cheap and usually served in a small glass known as a caña. “Ten years ago, every single guy in town was drinking beer,” says Joan Villar, editor of Gacetilla Cervecera and co-author of a comprehensive guide to Catalan beers. “It was just all the same beer, and we were fine with it.” For those looking for complex, challenging flavors, the default option was wine. Catalonia, which runs from the French border in the north, then along the Mediterranean to Valencia in the south, is especially known for the sparkling wine cava.

In the early 2000s, home-brewing beer began to spread among a small group of beer fans in the city. As they honed their skills, some of them began spinning off to become pioneer microbrewers throughout the region. Traditional beer styles from around the world appeared, from porters to brown ales. One day, a customer told Padró, “You have English ales, lagers, American-style IPAs—what’s missing is a Catalan style,” he recalls. “I thought, a-ha!” He began brewing D’hivern—which he calls a Catalan winter ale—with honey and rosemary, a common herb that grows wild throughout the area.

Catalan identity has made headlines recently, as a secessionist movement long relegated to the fringes has entered the mainstream. Since 2008, the movement has been making headway, gaining traction, as Catalonia felt increasingly overtaxed and underserved by the Spanish government in Madrid. The Catalan president, Artur Mas, is calling for a referendum on independence, which Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has already declared unconstitutional. From 2008 to 2012, the number of people supporting Catalan independence has doubled, reaching 46 percent. This September, hundreds of thousands of supporters formed a 250-mile human chain across Catalonia, from the French border through Barcelona to Valencia.

In Barcelona, where the streets are lined with Catalan flags and billboards feature images of the original Catalan constitution, regional pride is in full swing. Microbrewing, of course, is not activism, and these brewers are hardly waging the battle for independence with each bottle—sometimes a beer is just a beer—but that doesn’t mean developing a distinctly Catalan beer culture isn’t a marketing opportunity.

When it comes to thorny political issues (like secessionist movements), cultural branding matters. For centuries, a distinct Catalan culture, with its own language, cuisine, and customs (human tower, anyone?) has been part of the justification for regional independence. “Everyone knows Scotland—the kilt, the whiskey,” Ferran Civit, a member of the Catalonia National Assembly, recently told Reuters in reference to another distinct region planning to vote on independence in 2014. “But they don’t know much about Catalonia, so we want to make it an international ‘brand’ and publicize our struggle to become an independent state.”

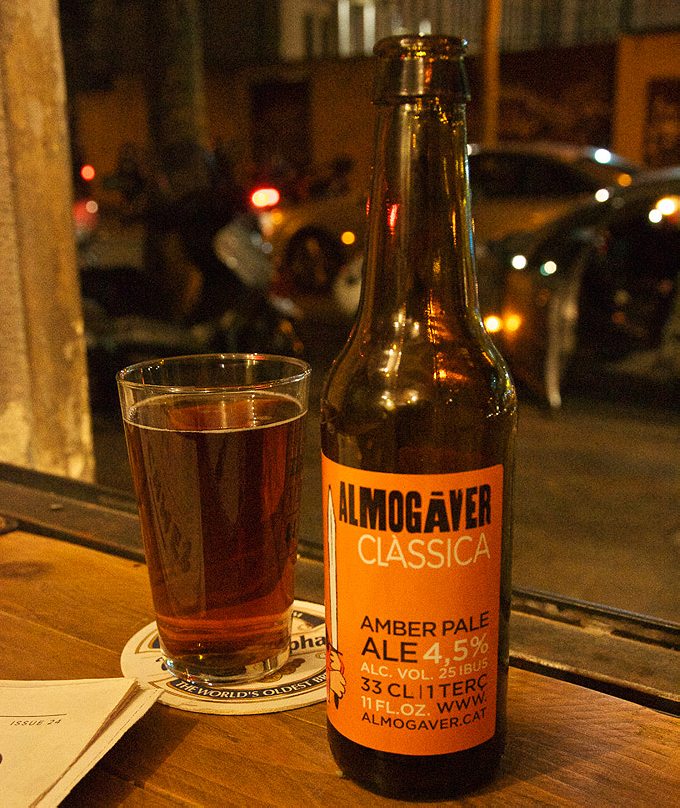

Craft beers have the opportunity to appeal to local drinkers by tapping into other local traditions. “The people here support Catalan over Spanish beer generally,” says Albert Sanchis, one of the founders of Almogàver beer. The cartoonish figure on each bottle of Almogàver is a rendering of medieval Catalan soldiers who went by the same name, but he seems friendly enough, sword notwithstanding. It’s “a little bit nationalist,” Sanchis admits with a smile.

The number of microbreweries has surged from about 10 in 2009 to nearly 50 throughout the country today.

Almogàver was founded in 2009, which makes it a veteran of the craft beer scene. However, while the region was late to the microbrewery trend by U.S. standards, in Spain, Catalonia was a leader. “In the history of Spain, most things are like this. They start in Catalonia and they spread,” Sanchis says with a laugh. The number of microbreweries has surged from about 10 in 2009 to nearly 50 throughout the country today. Specialty beer bars are also on the rise, as discerning consumers look for new brews and styles. Sanchis runs La Més Petita, a tiny bar offering eight taps and a handful of more traditional beer-friendly tapas (olives, anchovies, artisanal cheese, and the like) across the street from a gym, whose oversized windows show Barcelona’s more virtuous residents hitting the elliptical machine. In part he opened the bar, which is downstairs from the apartment he shares with his family, “so that my neighbors can get to know these beers, so that people who would drink a regular beer, an Estrella Damm, would try a different kind,” he says.

“[The independence movement] is sort of like the beer industry,” Sanchis says. It started five years ago with some people supporting independence, and support goes up and up. But it’s not something we’re fighting about—we’re not going after anyone,” he says, pointing out that he has a Spanish beer on tap.

Sitting in another of the city’s quickly proliferating specialty beer bars, Villar, author of the Catalan beer guide, notes that such a place—fashionably designed, with high-quality food, and packed on an unseasonably warm October afternoon—would never have catered to “beer geeks” in the past. (Screens behind the bar display a beer list and a running Twitter conversation about what’s available on tap today.) The increasing demand is being met by supply; in the 2012 edition of his book, he listed 350 beers, which he believes included every beer in Catalonia at that time. For 2013, he expects the list to top 500. “People want something different: they are always looking for something new,” he says of the boom. “Some of the older breweries realized their beer could have been brewed anywhere, so they started adding local ingredients, local flavors,” Villar says.

In general, brewers stick to adding herbs, fruit, and other ingredients to their beer to lend a local element, like Padró’s D’hivern. It’s difficult to source malt within Spain (there are only three malt companies, and they are tied up with the industrial beer giants), and most brewers prefer to order high-quality versions from Northern Europe. Hops are also not generally suited for cultivation locally. Due to the current vogue for bitter, hoppy beers, many microbrewers import American hops such as Cascade. However, at Més Petita, I try another of Padró’s beers, this one made with Tritordeum, a cereal developed through cross-breeding in Spain and cultivated in Catalonia. It’s one of my favorites, a dark golden brown with a balanced sweetness.

West of Barcelona, the three founders of Les Clandestines are growing a small plot of their own hops. In November, the off-season, the field is not much to look at, but the beer from last season’s crop is excellent, a light lager much in demand at a recent tasting in Montferri, the small town in which the brewery resides. Clandestines, which was founded in 2009, also produces a beer made with thyme, which is abundant. Miguel Angel del Castillo, one of the three founders, says that local people collect it around Easter, and he keeps bundles in the freezer next to his hops. They also use honey from another founder’s hives, housed just down the street. Castillo is especially proud that the brewery uses water from the nearby Gaia River, which he believes gives the beer a certain terroir.

While translating from one of his bottles, Castillo says, “It is a local beer, the water is local, so it’s all in Catalan.” The importance of the language to the region isn’t trivial; under Franco’s brutal dictatorship, the Catalan language was banned, as were some important cultural celebrations and traditions. Catalan was reintroduced as the primary educational language in the 1970s, but old battles over Madrid’s meddling can still flare up. This past spring the Catalan government and Madrid battled over increasing the use of Castillian Spanish in Catalan classrooms. The difference between the Castillan cerveza and Catalan cervesa maybe small, but it provokes strong feelings.

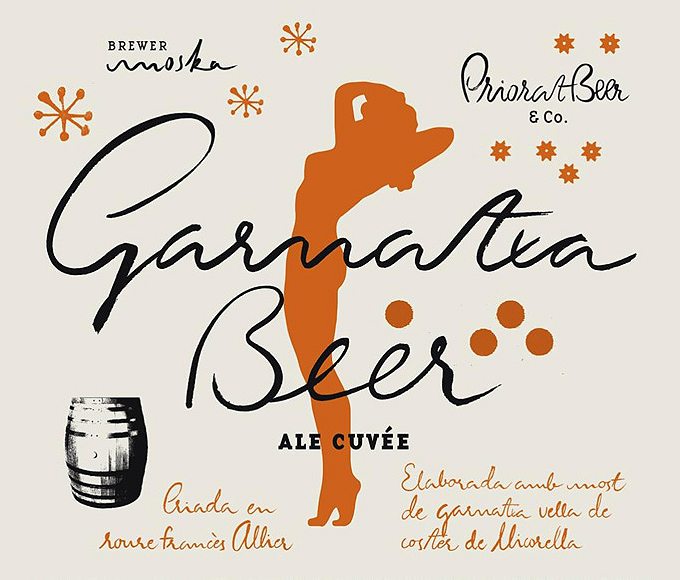

In Priorat, an area in southern Catalonia, a relatively new brewery called PrioratBeer&Co is trying to combine the area’s reputation for wine terroir with the move toward beer. While looking for a sugary addition to cause fermentation in the bottle, Santi Torrella, one of brewery’s four founders, says “We thought, we are a wine region, why not use grapes? They aren’t just sugar, they are flavor, aroma, everything.” For their Garnatxa beer, they age ales in French oak wine casks, then add garnatxa (also known as grenache) grape juice for the second fermentation. “We wanted to identify the beer with Priorat,” says Carol Van Waart, another founder. “We wanted to introduce [the region’s] beer, culture, music.”

The founders—two are winemakers, and the other two have a communications business—began brewing the beer at home, but decided to bump up production once their friends kept asking to buy bottles. Now, they’re selling the brew in chains across Spain and looking to export to New York next year.

Many brewers credit the rise of microbrewing and beer consumption to the Spanish economic crisis, which began in earnest in 2009. While the national economy is beginning to show signs of recovery, hundreds of thousands of people remain in dire financial straights (unemployment nationally remains at 26 percent; in Catalonia it is just under 23 percent). Spaniards tightening their belts moved away from the more expensive wine to cheaper options, primarily beer and hard cider. Household wine consumption fell in the last year by 4.8 percent, while beer consumption was up 1.1 percent. Even a fine beer costs less than a fine wine. At the same time, home brewers looking to take in some extra cash were eager to begin peddling their product.

Politics and business can be difficult to uncouple. Consider cava, Spain’s sparkling wine and the beverage traditionally associated with Catalonia. Freixenet, the largest cava producer, is now facing a boycott after its president, Josep Lluís Bonet Ferrer, told the New York Times that “Catalonia is an essential part of Spain,” and “that is how it should continue.”

Small brewers are most concerned with increasing quality and bringing new skills to Catalonia.

But the beer world remains controversy-free, and small brewers are most concerned with increasing quality and bringing new skills to Catalonia. The local ingredients they’re using are popular, but wouldn’t have worked if the beer didn’t ultimately taste good. As Villar puts it, “Who says, ‘Hey, let’s go get some beers. I want a curious one!’”

Sanchis doesn’t think the craft beer industry is there yet, but he believes they are well on their way. “I think in one [to] two years it is possible to have a really high quality Catalan beer,” he says. For now, brewers in Barcelona and beyond are tinkering and experimenting, drawing from the region’s traditional flavors and resources to create brews that celebrate Catalonia, but are meant for beer drinkers everywhere—even in the rest of Spain.