Jon Rosen travels to the pygmy homelands at a tense time in the Congo.

“Sécurité iko bien.” It was the baritone voice of Edgar Kamaliro, driver of our mud- strewn Mitsubishi Pajero, informing us—in a hybrid of French and Swahili—that all was safe on the road ahead.

We were somewhere on a dark and lonely road in the northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo and the news was reassuring. Though our route was supposed to be safe, we were still in one of the world’s most lawless countries, and the no-nonsense, linebacker-sized driver had spent much of the afternoon on his cell phone, calling friends in towns ahead of us to make sure no rebels were in the area. A veteran of these roads, he was used to such precautions. A decade earlier, this region, known as Ituri, was home to some of the heaviest fighting and worst human rights abuses of the long simmering Congo crisis, a web of inter-related conflicts that began in 1996 when neighboring Rwanda invaded to pursue militias responsible for its1994 genocide. Since then, aid groups estimate that more than 5 million people have died as a result of conflict in Congo’s east, mainly due to non-violent causes such as malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, and malnutrition.

After a long period of instability, the Ituri we planned to visit in June 2012 was home to a tenuous peace. Though various rebels still inhabited the region – occasionally plundering villages and terrorizing citizens – Ituri was safer than other parts of eastern Congo. Further south, in North Kivu province, a militia known as the M23, allegedly backed by Rwanda, had recently launched a rebellion and was battling government troops inside Virunga National Park. (Just last week, the M23 captured North Kivu’s capital Goma, and is now threatening to topple the government of president Joseph Kabila in the distant national capital, Kinshasa). Careful to avoid the M23’s path, we did not anticipate encountering any violence in Ituri. Yet had we carefully scoured the local French-language press, we would have learned about a warlord named Paul Sadala—nom de guerre Morgan—whose forces had recently attacked a market near our route, wounding several youths and raping 30 women. As we’d later find out, Morgan had also threatened to attack Epulu, the village that is home to the headquarters of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, a 5,200 square mile band of protected rainforest. This happened to be our destination.

Like Dan and Chris, my friends who’d flown in from Washington, I’d long been in the grips of a strange fascination with the turbulent history of Congo: a Western-Europe-sized country of 72 million people that remains stuck in a trap of conflict and failed governance, even as the Africa around it finally begins to prosper. In 2010, when I first moved to Rwanda, I had visited Goma, just over the Rwandan border, and climbed nearby Mt. Nyiragongo, an active volcano that leveled a fifth of the city in a 2002 eruption. Since then, I had wanted to get deeper into Congo’s vast, forested interior, though the expense of an entry visa and lack of a travel companions foolish enough to tag along had kept me on the stable Rwandan side of the border. Then, during a January visit to Washington, Dan and I took to discussing Congo. A few beers later, a tentative plan was hatched: sometime in 2012, we’d head to Ituri Forest and try to experience the life of its inhabitants. Five months later, after persuading our friend Chris, who went through international relations grad school with us, the three of us found ourselves headed for a visit to the Mangubos, a family of indigenous Mbuti hunter-gatherers. A pygmy people, the Mbuti account for nearly half of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve’s 20,000 residents, living in small family-oriented bands, hunting bush meat, and sleeping in huts of sticks and palm fronds..

A trip like this may seem strange to you. You could reasonably accuse us of a kind of exoticism. But people travel for lots of reasons. There’s beach tourism, sex tourism, wine tourism. This trip, for me, offered something a lot more interesting: a chance to feed our long fascination with the idea of pre-agrarian society. For 40,000 years, from the rise of behaviorally modern humans until the development of agriculture 9,000 years ago, all of our ancestors had lived somewhat like the Mbuti do today. More than anything, Dan and Chris and I just wanted a glimpse of what that past might have looked like.

Before joining the Mbuti in the forest, however, we first had to reach Epulu. Though we’d hoped to arrive by nightfall, the going along the washed out dirt road had been slow, and eight hours after leaving the border of Uganda, we still had 50 miles ahead of us. Swallowed by the fast-falling equatorial sunset, our Pajero trudged on into the darkness.

THERE’S BEACH TOURISM, SEX TOURISM, WINE TOURISM. THIS TRIP OFFERED SOMETHING A LOT MORE INTERESTING

There are approximately half a million pygmies in central Africa. They were once the region’s sole inhabitants, thriving in the forests of the Congo River basin by hunting bush pigs and antelope and gathering bananas, yams, beans, nuts, and honey. Around 1000 BC, they began to come in contact with Bantu farmers, who had traveled east from present day Cameroon and Nigeria as part of Africa’s great Bantu migration, one of the most dramatic population movements in recorded history. Farming gave the Bantu the ability to get more calories per acre, and their population soon exploded, making them the dominant group across much of sub-Saharan Africa.

By the late 19th century, when the first Europeans arrived in Congo, most pygmies still lived as hunter-gatherers, but had long traded meat and other forest products for the cultivated goods of their Bantu neighbors. Some, including the Mbuti, engaged in patron-vassal relationships with local farmers, working in fields in exchange for goods like iron, cassava, tobacco, and marijuana. Interaction was such that the Mbuti eventually lost their original language, adopting the tongue of the neighboring Bantu Bila or Sudanic Lese. In contrast to the tribal organization of farming peoples, Mbuti social structure remained organized by patrilineal bands: groups of up to 50 people, built around nuclear families in which women marry outside their group and relocate to their husband’s band. Since intermarriage with Bantu was uncommon, the Mbuti remained physically distinct, rarely exceeding heights of five feet. (The small stature of adult pygmy peoples is widely accepted to be the result of genetic adaption; theories include adaptions to diet limitations, forest mobility, low levels of vitamin D caused by a lack of exposure to ultraviolet light, and short lifespans).

In an era when Darwin’s theory of evolution first began to gain traction, Congo’s pygmies aroused great curiosity in the West, and were seen by some as “missing links” between apes and man. As such, many became victims of exploitation. During the period of the Congo Free State, when Belgium’s King Leopold II used a brutal campaign of terror and forced labor to extract a personal fortune from Congo’s rubber and ivory, several pygmies were sent on exhibition to Europe and America. Among them was Ota Benga, an Mbuti from Ituri Forest, who was part of a group recruited by an American missionary to be put on display at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. As his family had been murdered in Congo, Benga chose to remain in the US and eventually found a job cleaning cages at the Bronx Zoo. Seeing he was an attraction in his own right, the zoo’s management had him placed in a cage with several primates and encouraged him to shoot his bow and arrow. According to the New York Times, 40,000 people came out in a single afternoon to see the “wild man from Africa.”

Benga was soon released after a protest by African-American clergy, who charged the display was both inhuman and – in its support of Darwinism – anti-Christian. Though adopted by a Virginia family, he longed for his forest home and eventually grew despondent. In 1916, at the age of 32, he stole a gun and shot himself.

Almost a century later, shortly after 9:00 pm, our Pajero finally rolled into Epulu, our gateway to Benga’s forest. Though the 250-mile drive took more than 11 hours, our trip had progressed without any major hiccups. The only severe glitch had occurred the day before our departure, when Emmanuel Munganga, the Congolese guide we’d hired to join us, had emailed to cancel because he “ate the poison.” Home in bed recovering (he’d later tell me “jealous people” had tried to kill him), Emmanuel had dispatched his friend Nelson Munganga (no relation), and our journey continued as planned. From the Rwandan capital Kigali, where I was living, Nelson and I traveled north into Uganda, where we met up with Dan and Chris, who’d just flown in from Washington. (Though Rwanda also shares a border with Congo, that route would have taken us straight through M23 rebel territory). From southern Ugandan town of Mbarara, we hopped a series of minivans to Mpondwe, a village of mostly tin-roofed shacks at the Uganda/Congo border. Despite concerns we’d be turned back by immigration (rumor had it some Westerners had been denied entry even though, like us, they had already acquired visas), we managed to cross without incident the following morning. Kamaliro, dressed in a black WNBA jacket, was there to meet us. After fueling up the Pajero, we headed west as Congolese Rhumba blasted from the tape deck.

Established in 1992, and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site four years later, the Okapi Wildlife Reserve is one of Africa’s most impressive and least visited natural wonders. Occupying a fifth of Congo’s Ituri Rainforest—which covers an area larger than Ireland—the reserve is home to elephants, leopards, and chimpanzees, but is best known for its namesake okapi: solitary forest dwelling animals, with giraffe-like ears, zebra-like striped hinds, and tongues long enough to lick their eyes. After 1887, when the explorer Henry Morton Stanley wrote of an elusive leaf-eating donkey described to him by natives, the okapi was surrounded with a unicorn-like mystique throughout much of the West. Proving its existence had been no easy task. Few in number (it’s estimated there are currently between 10,000 and 20,000 in Congo) and extremely wary of humans, okapi are virtually impossible to spot in the wild. In 1901, when Sir Harry Johnson, then British High Commissioner of Uganda, set out on an expedition to find one, he managed to acquire pieces of hide and a full skeleton, but did not see a live animal.

Aided by Mbuti hunters, Europeans eventually managed to capture a live okapi; by 1952 the Belgian colonial government had opened a capture and breeding station in Epulu to export the animals to zoos around the world. Though the station was destroyed by war following Congo’s 1960 independence, it was re-built in 1987 as part of the Okapi Conservation Project (OCP), an initiative launched by the Florida-based White Oak Conservation Center in conjunction with the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature, Congo’s national wildlife authority. Founded to protect the species and its habitat, the OCP has been raising, breeding, and studying the okapi since, while holding several “ambassador okapi” on its compound. Over the years, the project has persevered through some extremely trying circumstances. Since rebels backed by Rwanda overthrew longtime Zairian dictator Mobutu Sese Seko in 1997, Epulu has been overrun by several rebel armies and has occasionally been on the front lines of rebel violence. The worst of the fighting came in 2003, when a group known as the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, led by millionaire turned rebel boss Jean-Pierre Bemba, occupied the project headquarters, battling opposing militias on site.

Though a no-go zone for tourists during the height of the Ituri crisis, Epulu has received a modest stream of visitors since large-scale hostilities ended in 2006. There are rewards for those willing to brave Congo’s roads and lingering rebels. Perched on a bend of rapids along the banks of the Epulu River, the picturesque OCP headquarters is the only place in Congo where one can realistically expect to spot an okapi; it is also within a short walk of several Mbuti homesteads. For a modest fee, government wildlife rangers can arrange homestays with families like the Mangubos – one of several ways the project supports the reserve’s Mbuti and non-Mbuti inhabitants. At the time of our visit, the OCP employed 92 local staff, including 53 Mbuti, many of whom gather and prepare leaves to feed the animals. Over the years, it has also supported initiatives to build schools, health clinics, and water sources.

Today, the OCP also works closely with the wildlife rangers to thwart networks of illegal poachers that continue to operate inside the reserve. With ivory prices at record highs – largely due to rising demand in China, Vietnam, and the Philippines – the poaching of elephants is of particular concern, as it is across much of Africa. According to Okapi Wildlife Reserve Director Jean Joseph Mapilanga, the reserve’s elephant population is estimated at 3,500, about half of what it was a decade ago. Despite stepped up patrols by rangers—often in conjunction with the Congolese army— the vast jungle terrain remains difficult to protect. Operations are highly dangerous and sometimes end in firefights. Often, government soldiers—who frequently go unpaid—are complicit in the killing of elephants and subsequent smuggling of ivory.

Though they are sometimes caught in snares, okapi are generally not targeted.

“The okapi is an emblematic animal,” Mapilanga told me. “Okapis have a special status.”

SEVERAL YEARS BACK, AN AMERICAN TOURIST DROWNED IN THESE RAPIDS

Our first morning in Epulu, we awoke to the hum of rapids. Pushing aside the curtains at the wildlife reserve lodge gave way to a view of sunlight piercing through the morning fog and dancing off the river. The wide shallow waters, more than 100 meters across, meandered slowly, pooling in swirling eddies and frothing behind jagged rocks. Here, in this so-called land of misery, was one of the most tranquil sites I’d seen in Africa. Not that it was without danger: Several years back, reserve officials told us, an American tourist – like me, named Jonathan – had drowned while swimming in these rapids.

Swimming off the agenda, we started instead with a visit to the okapi. Accompanied by ICCN ranger Michael Moyakeso – who donned a faded green uniform, green beret, and rusting AK-47 – we spent an hour strolling past enclosures that housed the project’s 15 ambassador okapi. Most of the animals, Moyakeso told us, were born in captivity to parents captured in the wild. Behind their fences, they seemed to disregard our presence, munching on leaves and enjoying the shade of their compound.

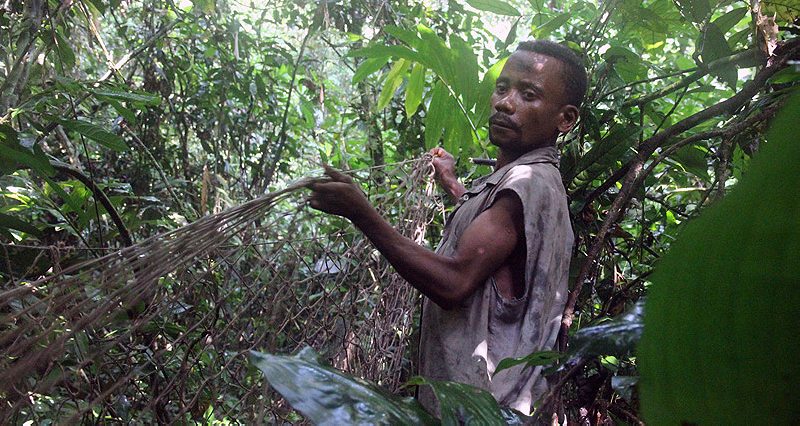

We returned to project headquarters to find a small group of diminutive, bearded, barefoot men. Assigned to bring us back to their homestead, while carrying our provisions—including tents, cooking pans, and sacks of rice—they led us on a jungle caravan, with Moyakeso and an additional armed ranger in tow. We crossed a bridge over the river, and turned onto a narrow forest path, where the balmy Epulu climate quickly became cool and dark. Giant hardwoods, older than Congo itself, rose hundreds of feet above us, their snarled roots forming hurdles to our path. On the ground, we marched past sagging underbrush, stinging nettles, and fallen fruits and nuts, some as large as soccer balls. Every few minutes, we came across columns of army ants, marching in flawless single file. Once, I neglected to watch my step, and the column proceeded up my leg. I immediately felt the sting – each one relatively mild but collectively a torment – and spent the next five minutes frantically brushing them off.

FOR A GROUP THAT LIVES APART, DEEP IN THE FOREST, THE MANGUBOS MAKE EXCELLENT HOSTS

It was an hour and a half to the Mangubos’ camp, including a ten-minute break for shots of locally brewed cassava wine – taken from a rusted can of tomato paste that Benard, one of our Mbuti porters, had found along the path. The settlement consisted of 14 stick and leaf huts, each no larger than a three-person tent, arranged in a clearing not more than 30 yards across. In the center, dozens of Mbuti stood to welcome us. Women in flowered kangas began to sing and dance. Children, half naked, giggled and stared. Men, dressed in grimy western T-shirts and cut off shorts, approached to shake our hands. Among them was the chief, Shaban, the eldest of the Mangubo brothers. “2006 NFL Pro Bowl,” his hat read. “Honolulu.”

I’m not so naïve as to think the warm welcome had nothing to do with the fact that we were, in fact, paying guests. But given the transactional way we all came together, they seemed remarkably relaxed and genuine. For a group that tends to live apart from much of the rest of mankind, deep in the forest, the Mangubos make excellent hosts.

After our introductions, and lunch prepared by a cook that had joined us from town, we spent much of the afternoon lounging around a central fire, chatting with our Mbuti hosts (most spoke some Swahili, which meant we could use Nelson as a translator) and watching in awe as the Mangubos “relaxed.” In planning the trip, Emmanuel had mentioned there’d be “smoking the marijuano (sic) around the fire.” Yet we were a bit unprepared for just how this was done. Sitting on an assortment of wooden logs and stools, the Mangubo brothers passed around bamboo bongs, blunts the size of small cigars, and a narrow pipe that was longer than they were tall. Some consumed the bang in moderation, yet Benard, already distinguished by his penchant for Mbuti homebrew – nursed his bong for hours. The party continued as the light beneath the canopy faded, ushering in an evening of drumming, song, and dance.

THE CHALLENGES OF FOREST LIFE ARE PLENTY

Not that life is all bang, blunts and bongs for the Mangubos. Though somewhat shielded by the forest, the Mbuti have not been immune to eastern Congo’s array of post-Mobutu era conflicts, including the occupation of Epulu by Bemba’s rebels, who were branded “les Effaceurs” (“the erasers”) for the manner in which they tortured, massacred and “erased” their enemies. Though those rebels did not consider the Mbuti to be foes, they also did not spare them of bloodshed. In early 2003, reports surfaced that Bemba’s troops in Ituri were murdering pygmies and feasting on their sexual organs – in the belief it would give them strength on the battlefield.

“They were threatening to eat us,” Abater Sukali, one of the Mangubo brothers, told us. “So we decided to run deeper into the forest.”

Even in times of relative peace, the challenges of forest life are plenty. Despite belonging to a family of hunters, most of the Mangubo children displayed prominently distended abdomens, a sign of protein deprivation. Though families living near Epulu do have some access to modern medicine—in part through support of the OCP—overall Mbuti rates of infant and child mortality are astronomical. According to one 2007 study, life expectancy of a Mbuti at birth is just 15.6 years; even a Mbuti who reaches age 15 lives on average to only 35. Education, too, is a major challenge: while several of the Mangubos had attended school in Epulu, most dropped out before their teenage years. They couldn’t afford the fees, and besides, there’s a prevailing belief among other Congolese that pygmies belong in jungles and not in classrooms. Emmanuel, in planning our trip, had distilled the mindset perfectly. “These people are very short and very stupid,” the Goma-based guide, no taller than five feet himself, told me. “But, really, they know how to survive inside the forest.”

Many Mbuti agree at least that they are not meant for modern life. Unlike many of Africa’s relic hunter-gatherers, the Mbuti have largely avoided external pressure to abandon their traditional livelihoods, move to permanent settlements, and integrate into a 21st century society. In this sense, Congo’s state decrepitude and subsequent lack of development have worked to their advantage. In neighboring Tanzania, by contrast, authorities have pledged to “transform” the semi-nomadic, baboon-hunting Hadza. In Rwanda, where the government does not recognize ethnic groups in an effort to avoid divisions that led to genocide, Batwa pygmies are simply “Rwandans.” With Rwanda almost completely de-forested, Batwa can no longer hunt; most now live in government housing – often in remote, windswept settlements – and face some of the highest rates of poverty in the country.

In Congo, where a horrendous road network has kept Ituri Forest insulated from commercial logging and large-scale agriculture, the Mbuti are far less threatened. Despite being a protected forest, the Okapi Wildlife Reserve is not a national park, which means its Mbuti residents are allowed to hunt, provided their prey are not elephants, okapi, or other endangered animals. Several years back, Shaban told us during one of our fireside chats, the Mangubos had moved to the roadside at the encouragement of a local NGO, which gave them jerry cans, cooking pans, and seeds to take up farming. There, schools and health care were more accessible. Yet the arrangement turned out to be short lived. Not only was the sun too strong outside of the forest, but moving into town also upset the delicate, centuries-old balance of trade between the family and their Bantu neighbors. In particular, Shaban told us, many local farmers were upset that the Mangubos, who previously worked in their fields and exchanged bush meat for their crops, had begun planting on their own.

“The Bantus used greet us when we passed them on the street,” Shaban told us. “But after we started farming, they would just tell us to fuck off.”

HUNTED ANIMALS HAD TO BE CONSUMED IMMEDIATELY, AND THEREFORE SHARED

Despite the experiment with agriculture, the Mangubos are still most in their element after leaving their camp with nets and spears. The hunt, which took place on our second day with the family, was the most anticipated segment of our trip, in part because of its significance to the long-meditated discussion over mankind’s “state of nature.”

To early modern philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, humans were not inherently social, but entered into society at a later stage to achieve certain individual aims they could not get on their own. In Hobbes’ world, the state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short;” only in the face of universal quarrel did humans cede their natural liberty to a Leviathan, or state, that secured their right to life. To be fair, it is thought that Hobbes and other bearers of the liberal philosophical tradition did not view their accounts of the state of nature as historical truths, but “merely as hypothetical and conditional reasonings, fitter to illustrate the nature of things, than to show their true origin,” as Rousseau writes at the beginning of his Discourse on Inequality. Nonetheless, as the political scientist Francis Fukuyama argues in his 2011 book The Origins of Political Order, the importance of these writings to the development of Western political thought makes it fair to contrast them with the very different story that biology and anthropology have taught us about the nature of human origins. As Fukuyama writes, “there was never a period in human evolution when human beings existed as isolated individuals… It is in fact individualism and not sociability that developed over the course of human history.”

As Fukuyama explains, even man’s primate ancestors were hardwired with natural faculties that nurtured cooperative behavior. Key were the concepts of kin selection, in which individuals behave altruistically toward kin in proportion to the number of genes they share in common; and reciprocal altruism, in which unrelated individuals – faced with repeated interactions – learn to cooperate for mutual benefit. In the real “state of nature,” humans were family-based, living in bands of kin, much like the Mbuti today.

Rather than a modern state, groups were held in line by what the social anthropologist Ernest Gellner called the “tyranny of cousins,” under which, Fukuyama writes, “your social world was limited to the circles of relatives surrounding you, who determined what you did, whom you married, how you worshipped, and just about everything else in life.” Critical to this group orientation was the physical nature of the hunt. The logic is simple. Since man lacked a means of preserving meat, hunted animals had to be consumed immediately, and therefore shared.

True to form, the Mangubos’ hunt was nothing if not a group exercise. Setting off on a path behind the camp, we joined a procession of more than half the family’s adults. Stopping at a clearing in the thicket, we watched as the Mangubos gathered sticks and set a small fire: a ritual, we were told, meant to summon the ancestor spirits – who were considered to be active hunt participants, even though not physically present. From there, we trudged on before stopping again as Benard – on a rare break from the bamboo bong – carefully fastened a 20 foot net between two trees. Soon, a group of Mangubo women began to thrash into the brush and hoot like animals. The goal, we were told, was to scare the would-be prey into the net.

Three hours later, after the family had moved the net to several locations, a high-pitched wail alerted us that the hunters had a catch. Rushing toward the scene, we saw two men pinning down a duiker – a small forest antelope slightly larger than a fox. After a quick killing by machete to the jugular, we trekked back to the camp with the prey in a small basket. Within minutes Shaban had carefully skinned the animal, children were playing with its innards, and the head was roasting on the fire. Accustomed to the tastes of Westerners, the family reserved the leanest cuts for us. Later that evening, our last in Ituri Forest, we dined on tender steaks of duiker.

A CHILD OF THE MODERN WORLD, I COULD NEVER LIVE LIKE AN MBUTI. BUT FOR A MOMENT THERE, IT FELT WORTH TRYING

As we sat around the fire that night, I couldn’t help but dwell on the contrast between the highly social Mbuti world and the war torn-Congo around us. From our taste of Mbuti home life, it wasn’t hard to see how bands of kin, kept in line by Gellner’s tyranny of cousins, had lasted for tens of thousands of years as the dominant form of social organization. Life on the Mangubo compound, unlike the world outside the jungle, was both peaceful and egalitarian. Though stuck together in the same band since birth, none of the Mangubo children quarreled; despite Shaban’s status as chief, he was no better off than his siblings, and didn’t appear to hold coercive power. Unlike much of rural Africa that I had seen, where women are visibly second class, forced to till the land while their husbands sit under trees getting drunk on homemade alcohol, it was clear the Mangubo wives were respected. A child of the modern world, I could never live like an Mbuti. But for a moment there, it felt worth trying.

With the smoking, drumming, and dancing in full swing, my mind drifted to an article by the geographer Jared Diamond that I’d read – along with Fukuyama’s book – in preparation for our trip. In the piece, titled “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,” Diamond argues that the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture – long considered a fundamental driver of human progress – was actually a colossal blunder. According to Diamond, the advent of agriculture led to poor nutrition, due to the adoption of a less varied diet; intermittent famine, due to reliance on crops that periodically failed; epidemic disease, which emerged from the crowding permitted by farming societies; and a remarkable loss of leisure (in a rich forest, feeding oneself by hunting and gathering, as evident by the Mangubos’ lazy days around the fire, doesn’t actually take up that much time). Perhaps most importantly – particularly in the context of the Congo – agriculture also formed the basis for social stratification and, ultimately, war.

“Hunter-gatherers have little or no stored food, and no concentrated food source, like an orchard or a herd of cows,” Diamond writes. “Therefore, there can be no kings, no class of social parasites who grow fat on food seized from others. Only in a farming population could a healthy, non-producing elite set itself above the disease ridden masses.”

For all the challenges of the Mangubos’ forest life, I started to think that Diamond might have been right.

MORGAN’S MEN THEN DID WHAT NO OCCUPYING ARMY HAD DONE BEFORE: HARM THE ANIMALS

The news arrived on a Monday morning, nine days after we’d left Epulu and eight days after we’d safely departed Congo. Our trip back was a bit rougher than our ride in: delayed by a flat tire, and then by engine troubles, we spent a night in Kamaliro’s hometown of Beni, a reasonably functioning city of 100,000 a few hours from the Ugandan border. Still, we managed to avoid the instability we’d all read about and each made it home in one piece: Dan and Chris to Washington, Nelson to his home in Goma, and myself to the tidy Rwandan capital, Kigali. It was there that I received an email from Kamaliro.

“Hello jon! How are you?” he wrote (either his English was better than he’d led us to believe or someone else had composed the message). “I want to inform you that the Okapi sation of Epulu was been attaked by rebels yestarday. An occasionnel correspondant inform that Six okapi are kiled by Morgan, the rebel comender. I dont know the nomber of gard park who was died in this attak. If i receive the confirmation, i will inform you. Regards, Kamaliro your driver.”

As days passed, and I checked in with Emmanuel, Nelson, and OCP staff, the details of Morgan’s attack became clearer. At 5:00am on a Sunday morning, a group of 35 naked fighters attacked and overpowered a small group of armed rangers stationed outside the project headquarters. Under the “protection” of a local witchdoctor, Morgan’s men proceeded to kill six people – including two rangers – loot and burn the Congolese wildlife authority offices, and kidnap several locals: men to carry their spoils and women and girls to use as sex slaves. According to some reports, the fighters burned two of their victims alive before feasting on the charred left leg of one of them. To add insult, Morgan’s men then did what no occupying army had ever done before: harm the project’s flagship animals. By the time they fled into the forest, the rebels had killed 14 of the 15 ambassador okapi; the 15th died a few days later, after Congolese troops arrived to re-take the village. The soldiers, poorly disciplined and underpaid, then went on a rampage of their own, looting the charred project offices and raiding abandoned homes inside the town.

The attack, which occurred when Mapilanga and his deputy were out of town, was a particularly grisly chapter in the new wave of militarized poaching that has recently surged across Africa. Morgan, I learned, had made big money off the ivory trade and didn’t appreciate efforts of the project to thwart his men from killing elephants. According to Rosmarie Ruf, OCP co-founder, Morgan had threatened Epulu three months before, but his men never came.

As news of the attack set in, I tried not to imagine what might have happened if we were present. Instead, I thought of the Mangubos. At home inside the forest, they hadn’t directly experienced the attack. Still, the project’s near destruction will affect them moving forward. Though the family survives largely by trading game meat, several Mangubos were employed by the OCP to care for the now dead okapi. As tourists, we injected about $70 into the family coffers – a modest sum by Western standards, but money that clearly helped. Following the attack, it’s unclear when visitors might return. Although OCP staff have vowed to continue the project, rebuilding will take time and money, and little can be done with Morgan still on the loose. Authorities nearly nabbed him in August, after he was captured by a rival militia, which offered to turn him in for $10,000. Morgan, however, beat the government to the ransom, bought his freedom for $20,000 and snuck off into the night.

Thinking back to the Mangubos, I wondered if the attack had surprised them. Or, maybe, given that they seem to know everything that is happening in the forest, they had known this was coming, too.

Then I remembered the drawing. Sitting around the fire one afternoon, I had asked Wendo, a boy of about ten, if I could look though his primary school notebook. Flipping through its pages, I came across an image drawn in blue and black pen. In it, a machine gun toting stick figure stood on top of an okapi, engaged in a firefight with another cartoon man. It wasn’t an exact representation of Morgan’s attack, but it struck me as eerily similar. Conjured from a boy’s imagination, it was probably just a coincidence. But news of the attack made me wish Wendo had told me something about the picture. Struck by the image, I had actually called him over to the fire. But Wendo was particularly shy. When I pointed to the drawing, he scampered off, embarrassed.