A pre-history of techno, the sound of black Detroit.

It’s a hot May afternoon in Philip A. Hart Plaza, the open square at the heart of Detroit’s revitalized downtown. The seven interconnected towers of the Detroit Renaissance Center—an immense development built in the 1970s that failed to spark the urban renewal promised by its name—rise ominously in the background, like something out of science fiction. Young people mill about near the waterfront of the Detroit River, a lively contrast to Detroit’s perennial reputation as America’s most depressed major city. They’re here for the 17th annual Movement Music Festival, which, for, any American interested in underground dance music, is one of the most important events of the year.

Hart Plaza lies just a few blocks away from the original location of the Music Institute, which three decades ago managed to unite the city’s various party scenes into a single culture identified with the genre techno. Back then, the city’s urban core was a shell of its booming post-war self. Today, it’s becoming one of America’s coolest cities, with vibrant art and food scenes, a compelling narrative, and all the assorted problems of gentrification.

The concrete playground of Hart Plaza reflects all of Detroit’s recent history—boom, bust, rebirth—and is a fitting place to host America’s best dance party. For three days each spring, Movement fills six stages with hometown heroes and their numerous overseas disciples (last year, the pioneering German electronic music band, Kraftwerk, took the stage), and draws about 100,000 people over the course of the weekend. Yet despite the changes it both catalyzes and reflects in the city around it, Movement has stayed true to Detroit’s roots as a crucible for musical talent.

Like everything in Motor City, Detroit’s electronic music scene has its roots in the auto industry. The city’s population surged during the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when black workers from a hostile South came north to start new lives. Detroit was generally more welcoming and offered higher wages than other cities, yet racially discriminatory housing policies still forced black communities to concentrate in neighborhoods like Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, where they put down the early roots of Detroit music on Hastings and St. Antoine Streets.

The two areas became cultural hubs for people of all racial and economic backgrounds, rivaling New Orleans’ Bourbon Street with their extravagant nightlife and gambling cultures, all set to a soundtrack of blues and jazz. Most of the residents were of mixed-income, African-American descent, but the local “black and tan” venues entertained black and white audiences alike, one of the few instances of interracial socializing in a time when segregation was rampant. In Black Bottom, pianists like Big Maceo Merriweather, Charlie Spand, and Speckled Red played a danceable strain of blues called boogie-woogie, influenced by the surge of artists rushing in from the Mississippi Delta. The adjacent Paradise Valley played host to national jazz acts like Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Dizzy Gillespie. Though Detroit produced and hosted live music, a lack of recording facilities meant that many Detroit musicians had no choice but to relocate to Chicago.

Berry Gordy, who would go on to found Motown Records in 1959, first came to Detroit from Georgia in 1922 and received much of his early musical education in Black Bottom, where he was a regular at Joe’s Record Shop, owned by the influential producer Joe Von Battle. Following World War II, a second wave of migration brought a new generation of musicians to the city, even as the nationwide vogue for large-scale highway projects destroyed Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, bulldozed to make way for the Chrysler Freeway. Many residents were relocated to the Brewster-Douglass and Jeffries Housing Projects, which went on to produce several of Motown’s biggest artists.

Over the next 13 years, Motown became synonymous with Detroit soul, producing 110 Top 10 hits between 1959 and 1972. In those years, Motown was the highest-earning black business in America. But Detroit’s boom years came to a sudden, catastrophic halt as deindustrialization set in. After the riots of 1967 and a series of financial disputes with his songwriters, Gordy moved the label’s headquarters to Los Angeles in 1972: the end of an era in Detroit music.

The following decade is often overlooked in the story of Detroit’s music scene, but it was during the otherwise depressed 1970s that the foundations were laid for the birth of techno. Kids who grew up in those years heard regularly about godless communists overseas and robots coming to take their parents’ jobs at the auto plants. On the radio, a DJ named Charles Johnson, better known as The Electrifying Mojo, captured the city’s imagination with shows like “The Landing of the Mothership” and “Midnight Funk Association.”

Instead of churning out hits, the genre-bending program broke artists like Prince and The B-52’s, and played them alongside krautrock and Italo-disco, playing B-sides as often as hits. Johnson educated Detroit’s first wave of techno artists—musicians like Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, and Derrick May, known as the Belleville Three—with a curriculum of Motown and funk, soul and rock, new wave and punk. They lived in a musical and urban environment informed as much by the past as the future.

Through the 1970s, funk dominated Detroit’s airwaves, a marriage of jazz, R&B, and soul that favored rhythm over melody. The introduction of strings to the mix of brass, piano, and the standard rock instrumentation of drum kits and guitars transformed funk into disco, while new technologies allowed music venues to replace live bands with so-called disc jockeys—an entirely new (and cheaper) kind of performer. Dub music and Jamaican sound system culture had already transformed record-playing into creative performance. Innovations like slip-cueing and beat-matching, developed in New York in the late ‘60s, had introduced musicians to the concept of mixing a continuous flow of music for the dance floor. But it wasn’t until the ‘70s that Detroit’s aspiring musicians started trading their guitars for turntables.

Disco’s reign would be short-lived. The rock-oriented music industry had no space for a musical scene that would render its stars obsolete; they had even less space for a genre built by and for the city’s black, latinx, and queer communities. Though disco died a premature death, the genre set the stage for modern dance music, putting DJs in the spotlight for the first time. This vital period served as a bridge between Detroit’s Motown era and the birth of techno, best exemplified by the work of Ken Collier, a local DJ popular in the LGBTQ community.

Detroit house DJ Alton Miller says listening to Collier’s music “changed my life. At this time, disco was ‘dead’ so he was playing what we called ‘progressive music.’ […] It was still acoustic but things started to become a little more electronic.” In a time before the internet, young people had limited opportunities to hear new music and dance, so a rising crop of Detroit DJs like Delano Smith, Stacey Hale, and Felton Howard provided a space for exploration and a respite from the daily struggles of life in an increasingly depressed city.

Though Collier garnered an international reputation, Detroit’s authorities suppressed the city’s emergent dance music culture through both violent policing that targeted minority communities and bureaucratic indifference. Nonetheless, Detroit continued to turn out innovative sounds at club venues like Bookie’s, Taboo, The Downstairs Pub, Tremors, Cheeks, L’uomo and pretty much anyplace that could host a crowd and power a set of turntables, from local high schools to YMCAs. A community of DJs emerged, driven as much by competition as camaraderie. DJ Psycho of Detroit Techno Militia remembers growing up in the neighboring city of Flint and driving over to Detroit when “Plastikman was calling himself Richie Rich and Moby was performing at a bowling alley.” It was, he remembers, a city bursting with talent. “You could walk down the street and feel it.”

Cheeks played host to a particularly influential DJ named Jeff Mills, whose rapid-fire style churned through piles of disco records, often up to 70 per hour, mixing their rhythmic intros in quick succession to produce the sound we now recognize as techno. Mills would go on to become a founding member of Underground Resistance, a music collective which came to prominence as part of Detroit’s second wave of techno. These DJs fused an uncompromized sound with a DIY approach that sidestepped mainstream record labels, a conscious rejection of Motown’s hit-seeking formula. Unlike modern dance music, Underground Resistance was explicitly political in its lyrics, liner notes, and shows, influenced by the inner-city recession of the Reagan Era.

Economic and societal pressures were built into the psyche of Detroit techno from the first. Motown had left nearly a decade earlier, and while Detroit remained a city of music lovers, it no longer had the economy to incubate an artistic community on its own. The city ran instead on a spirit of self-reliance—the famous Detroit Hustle—which extended into the experience of finding music in the first place.

While at Movement last year, I met up with Ted Krisko of Ataxia, a longtime Detroit musician and promoter. We sat in the lobby of one of downtown Detroit’s new boutique hotels as Krisko talked about the hidden world of DIY techno in the second-wave era. “People would call the infoline and it would give you instructions of where to get a map to the party,” he said. “So instead of it being you call the infoline and get the address to the party, you were still rerouted and challenged and in a sense, vetted.” Krisko’s generation of musicians valued experimentation and a futuristic sound while creating a home for people on the fringes of society.

While musicians were informed by their stark surroundings, they were also, ultimately, optimistic; techno was not some dystopian reaction to the celebratory sounds of disco and Motown. Richard Davies, who began producing music after returning from the Vietnam War, coined the term techno by lifting it from The Third Wave, a book by renowned futurologist Alvin Toffler, which describes a future of “techno-rebels” who embrace technology rather than fearing it.

In 1988, Virgin UK released Techno! The New Sound of Detroit, a compilation disc that introduced techno to a UK audience already familiar with the squelching basslines of acid house. Since then, techno has proliferated across Europe, raising whole new questions about commercialism and class in a style of music built by outsiders in a city on the brink of economic collapse.

For the lay listener, techno became a catchall term for electronic dance music, the dreaded EDM primarily associated with white, privileged clubbers, and totally disconnected from its roots in the racial and sexual minority communities of a working-class city. It’s an obvious problem at mainstream transnational cash-grabs like Electric Daisy Carnival and Ultra Music Festival, but even underground music stalwarts like the online publication Resident Advisor sorely lack in representation of female, LGBTQ, and POC DJs. Though artists and collectives like Discwoman, Tuskegee Music, GHE20G0TH1K, and The Black Madonna—the latter declared Mixmag’s DJ of the Year for 2016—have done a great deal to bring different faces into the spotlight, cultural appropriation is as much a problem in the world of electronic music as it is in every other sector of the American culture industry.

One particularly egregious example was an EP titled Born out of Cheapness and Frustration Volume One, issued posthumously by one Ellis de Havilland of Gary, Indiana. Bunker Records’ press release described a troubled “genius” who died in poverty from heroin addiction. The music’s not bad; it also wasn’t made by Ellis de Havilland. Ellis de Havilland, in fact, does not exist: he’s a fictional alter ego for Perseus Traxx, a European producer who falsified a back story as a cynical marketing ploy, charged with all sorts of assumptions about race and class.

Since those first years, Movement has gone from a free event to a paid one, passing through the hands of several directors along the way. Despite changes in leadership, Movement still plays an important role in the narrative of Detroit Rising, which is also the story of Detroit Gentrifying. Hart Plaza itself is now the centerpiece of one of Detroit’s many “revitalized” neighborhoods. As in similar urban zones across the U.S., rising rents have driven out a predominantly middle-class economy, replacing local businesses with high-end establishments and luxury apartments—the early stages of the trend that turned former underground capitals like New York, London, and Tokyo into velvet-rope and bottle-service cities. Growing electronic music scenes in Asia, Africa, and South America show promise, though most investment in those regions goes to venues that cater to the developing world’s growing elite.

MOVEMENT TODAY MORE STRONGLY REFLECTS A GENTRIFYING DETROIT THAN ITS WORKING-CLASS ROOTS

“At one point in time,” says Ted Krisko, “hand-to-hand flyering was how people found out about the party, which was much riskier. There was a far more intricate element of danger. […] I can’t speak for everyone, but for Detroit, the rave appeal had all of these elements of rebellion.” Walking through the festival grounds, rebellion appears to be in short supply.

A three-day pass costs $155, which is cheaper than most commercial events but out of sync with the economic realities of techno’s origins and of a city where 40 percent of the population still lives below the poverty line. “When festivals were free at Hart Plaza, more people were likely to wander downtown to people-watch and sample the offerings,” says local journalist Desiree Cooper. Sadly, she says, that’s no longer as common as it once was. Movement’s crowd and artist lineup are still noticeably more inclusive than your typical EDM festival, and Detroit’s club culture is still largely-artist driven, but still, Movement today more strongly reflects a gentrifying Detroit than its working-class roots.

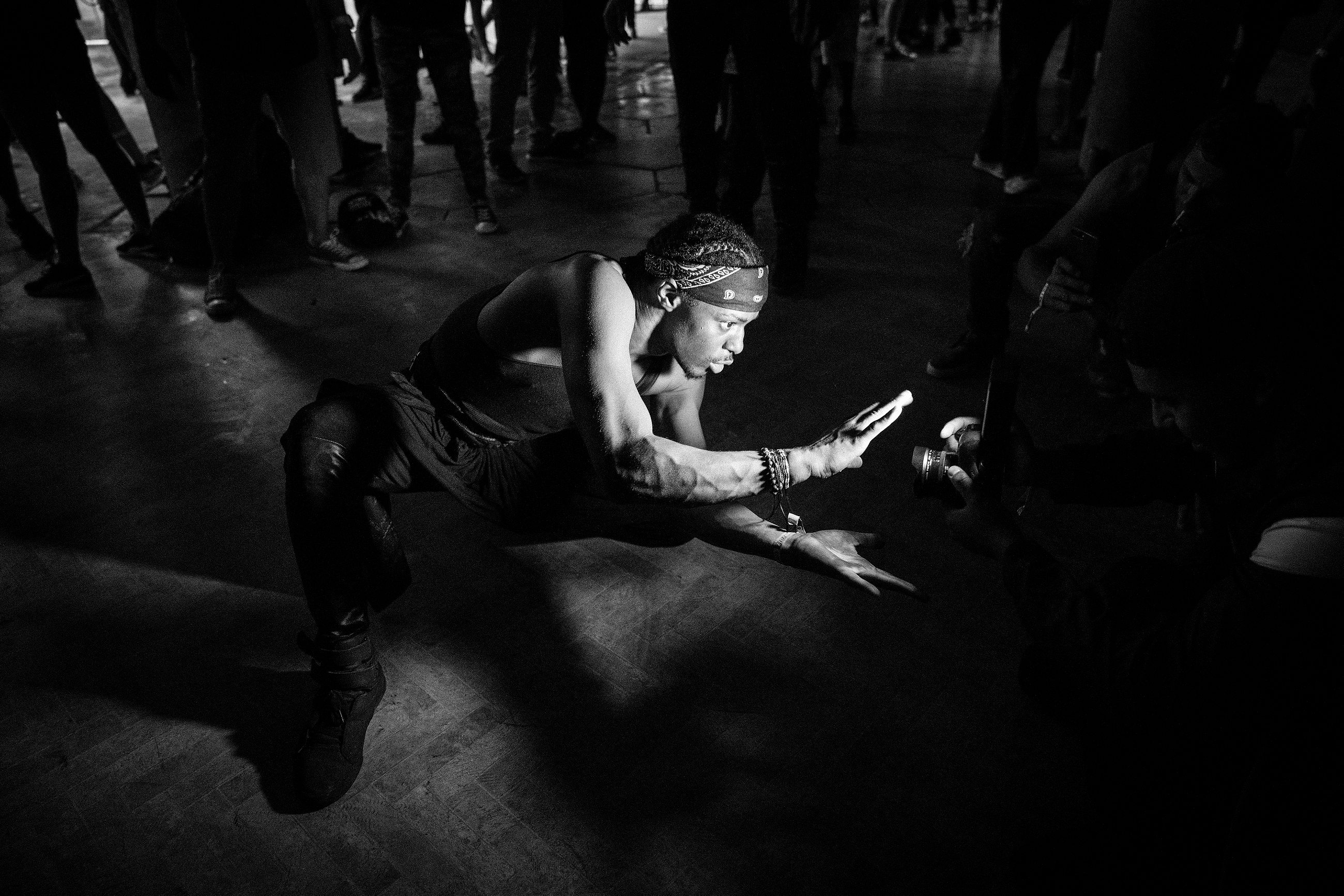

But EDM fans looking for a deeper sound are also fresh blood for Detroit techno and the wider culture of clubbing, creating a mix of faces that harkens back to the spirit of Black Bottom and techno’s early, vibrant roots. “We’re at a brink of a renaissance,” says Krisko. “There’s a huge appeal for quality vinyl DJs that have eclectic styles and are supportive of the origins of club culture: minorities, queers, misfits. There’s a pushback from a more authentic perspective. Artists have started bearing the flag for a return to the spiritual experience of creating energy on the dancefloor, playing music that provokes. [Audiences] still have that innate desire to go dance.”

Prior to the festival, I met local musician and producer Haz Mat at Cass Café in the historic Cass Corridor, a neighborhood known for its artistic community that’s currently experiencing its own gentrification-related growing pains. Despite rising rents placing new strains on local musicians, Haz Mat is optimistic about his city’s techno community. “It started here. So, you could come here and get a pure strain of what techno is. The founders of techno are still alive. You could get that right from the tap here in Detroit.”

“This is a place where you could come be a part of the culture,” he says, “and the world comes here to get that.”