Food accounts for 13% of cities’ carbon emissions every year. But a small league of C40 Good Food Cities, from New York to Quezon City, is hoping to change that.

BROOKLYN, New York –

Little about the culinary center serving New York’s Health + Hospitals agency evokes a home kitchen. Hair-netted cooks mix the ingredients for salsa verde in white bins the size of babies’ bathtubs. A row of combi ovens, gleaming and tall, roast hundreds of sweet plantains at a time. Nearby, a 200-gallon water bath chills reduced-oxygen packets of just-steamed yellow-and-white “sunshine” rice, preserving their freshness.

And yet, the 15,000 meals prepared daily inside this yellow brick building in Brooklyn to supply New York City’s 11 public hospitals and four nursing homes are meant to provide the same succor as a get-well bowl of homemade soup lovingly proffered by Mom on a sick day home from school. When plotting out menus, “What we wanted to do was say, what comfort foods would our patients enjoy?” says the center’s corporate chef, Philip DeMaiolo, who gets a little wistful when he remembers the pastina in brodo his mother used to cook him when he had a cold. “They’re lying in a bed, they don’t choose when the nurse comes in to take blood or measure their blood pressure,” he says. “We want them to at least be satisfied with what they’ve chosen to eat.”

Increasingly over the last two years, New York’s hospital patients are choosing some of the 25 plant-based meals DeMaiolo and his staff of 30 chefs and cooks have painstakingly devised. And it’s not just about replicating that home cooked meal. Rather, it’s part of a years-long calculated effort to reduce New York City’s food-based carbon footprint by 33 percent by 2030. Behind that goal is a nonprofit network of 96 global mayors called C40 Cities (so named back in 2006 when membership was just 40 cities). C40’s mayors commit to a science-based approach to limiting global heating while building healthy, equitable, resilient communities. Under that broader umbrella is the 55-city-strong Food Systems Network, which work together to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by improving food policies. A smaller subset of those 55 are part of C40’s Good Food Cities Accelerator program

To date, sixteen cities, including Copenhagen, Milan, Quezon City, Seoul, and New York, have joined the Accelerator. With urban populations consuming 70 percent of the world’s food, and animal-centric diets responsible for as much as 20 percent of a city’s total carbon emissions, Accelerator mayors recognize they can make a transformative change by tackling issues around what we eat. They’ve signed a pledge to improve our planet’s health by procuring and promoting more plant-based foods, using what’s known as the Planetary Health Diet devised by the EAT-Lancet Commission as a baseline. In this metric, meat and dairy take up a much smaller portion of a plate than perhaps has been traditional in some cultures. Cities also agree to cut their food waste in half from a 2015 baseline. In the process, they aim to improve the health and wellbeing of their most vulnerable residents. “The kind of programs that have most success within cities, and have been replicated most around the globe, are the ones that hit the climate, health, and inequity angles at the same time,” says Stefania Amato, C40’s head of food strategy.

As a requirement to be a member, C40 cities “have written climate action plans that address how they’re going to achieve a 1.5-degree C future,” explains Zachary Tofias, C40’s director of food and waste. Accelerator cities develop strategies with residents, businesses, and public institutions to make plant-based eating and reduced food waste more achievable for everyone. Some have amped up their composting efforts and compelled their agencies to cut back on the purchase of animal-sourced products, which can account for 75 percent of a city’s food-based emissions. They report their progress every year, using a data framework devised by the Carbon Disclosure Project. Finally, C40 checks this data to ensure cities have decreased the volume of the highest-emitting food groups in their purchasing, and reports are publicly shared.

Since different cities have different procurement policies and different mayoral priorities, there’s variation in strategy among Accelerator signatories. The city of Lima has helped build over 1,800 “bio-gardens” to make hyper-local produce available to its citizens. Since 2008, New York has required its 11 agencies to serve a plant protein for lunch and dinner at least once a week. But its food- based efforts in schools and hospitals—the largest public municipal systems of their kind in the U.S., each serving around one million students or patients per year—are where it has so far shined.

New York City children are now served culturally relevant, plant-based meals cooked from scratch every Friday, with more plant-powered options offered throughout the week; they also learn about the importance of healthy diets through school garden programs and visits to farmers’ markets. “Changing behaviors—that’s what this work is all about,” says Kate MacKenzie, executive director of the Mayor’s Office of Food Policy.

At Health + Hospitals, plant-based meals are offered as the primary option, and about 50 percent of in-patients are now opting for these plant-based meals during their stay—significantly more than in 2021, when the agency’s plant-centric initiative began in earnest. In 2023 alone, Health + Hospitals served more than 783,000 plant-based meals. Though there were previously vegetable-based options on the menu, says DeMaiolo, “It’s very easy to steam vegetables and call it plant based. But the thing is, people don’t enjoy them, and then you’re wasting food.” He says patient education has been a big part of the program’s success.

Every day, lunch and dinner menus feature a plant-based chef’s special and a plant-based alternative. Animal-sourced dishes turn up further down the menu. That daily special could be Puerto Rican sancocho, where plantains, garbanzos, pumpkin, and corn replace pork in a vegetable broth; or red curry tofu; or jerk mushrooms with collard greens and beans. “It’s a very diverse, cultural-type menu,” DeMaiolo says. That too is by design. Over 60 percent of patients served at NYC’s public hospitals are Hispanic or Latinx, 15 percent are Black, about six percent are Asian. Each patient has deeply held and diverse memories of what comfort food looks, smells, and tastes like to them.

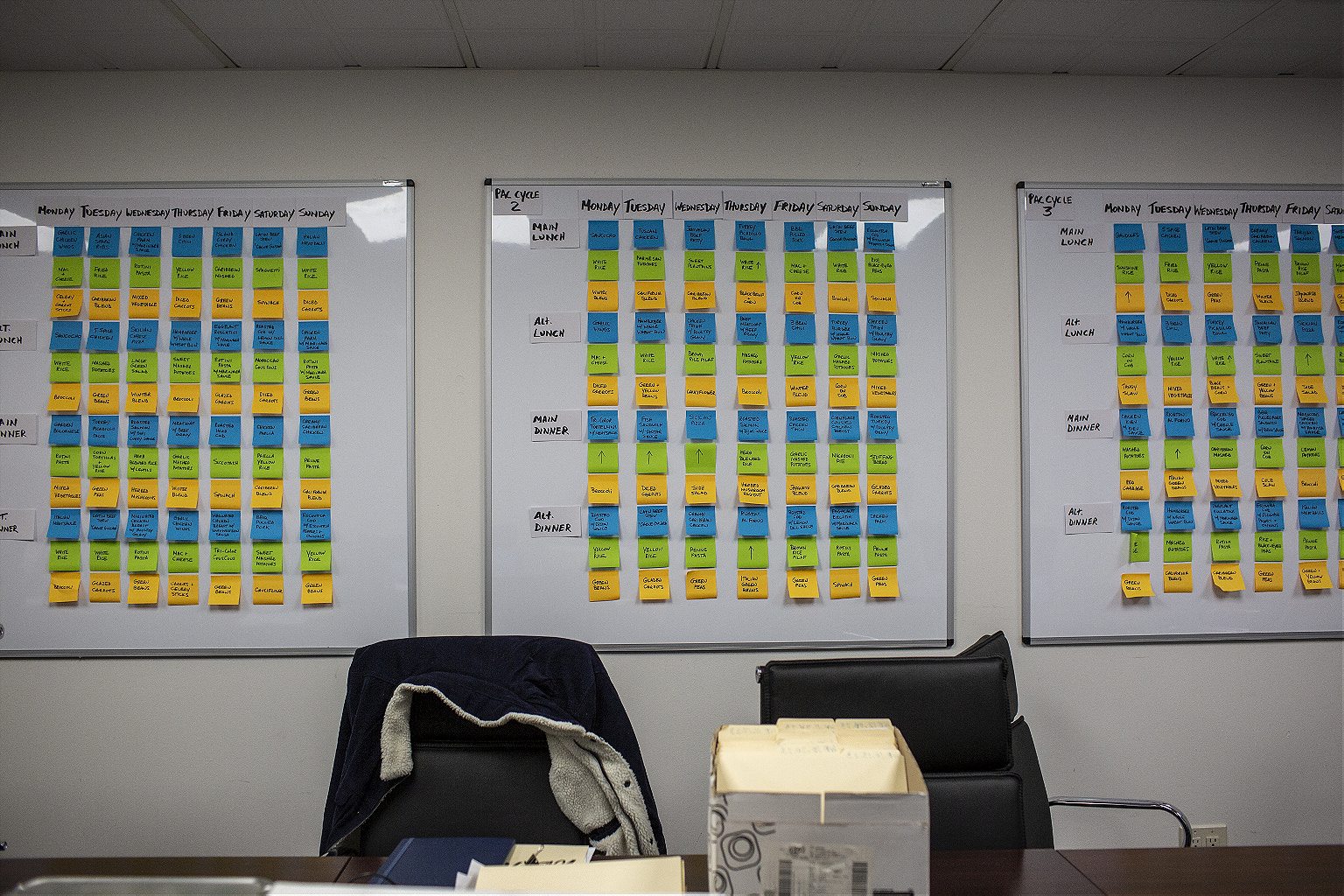

Patients are visited by food service associates who break down what’s on offer. “They’ll go, ‘Mrs. Smith, tomorrow’s chef’s special is mushroom stroganoff over rotelli pasta,’ and they’ll explain exactly what’s in it to you,” says DeMaiolo. After the meal, the associate returns to the patient for feedback. “If a new dish is too spicy, I can turn that spice down. Then I’ll run it as a special again, see if that improves its rating,” says DeMaiolo. He considers any dish that scores 80 percent approval a homerun and adds it to the rotation.

This sort of innovation, attention to small details, and getting things just right befits a program in a city that was one of the founders of C40 back in 2006. “They’ve been a leader in a wide variety of the activities that we’ve undertaken,” says Tofias. This is the sort of tenacity necessary to participate in the organization, since C40’s approach is not to do the projects themselves, but rather to “support the sharing of good ideas that can help raise ambition and give confidence to mayors that they’re on the right track,” says Tofias. With a 90 percent overall approval rating for the plant-based meals New York’s Health + Hospitals are serving, and with even more plant-based meals about to come on the menu in other agencies, the city is well on track.