In rural British Columbia, Catalyst Agri-Innovations Society is harnessing the power of poop.

Abbotsford, BRITISH COLUMBIA—

It takes no more than an Uber ride with the window down across Abbotsford, B.C. to notice that you are in Canada’s agricultural capital. The scent of Cedar and Spruce that envelops most of the Fraser Valley, the Southwestern region of British Columbia that neighbors Washington State, is overpowered by the farm smells of wheat, fresh grass and, especially, cow feed—in all parts of its cycle.

The odor of cow manure grows faint to new visitors after a few days, and some locals don’t detect it at all, but, despite living in the area for years, Chris Bush couldn’t leave it alone. That odor was a sign of a problem with local agriculture; one he wondered if he could fix.

Back then, he was an account manager losing interest in his job selling two-way radios at a regional telecom company. One night, trying to disconnect from work, he read a sidebar story in Popular Science Magazine about a farm in Vermont that made electricity from cow manure—the same dung he’d get a faint whiff of every morning on his drive to work. A lightbulb turned on in his mind.

“We have massive amounts of manure lying around, and our environment is suffering from it,” he says. “It seemed to me like there was a gigantic gap between what is being done and what’s possible here in Abbotsford.”

Bush was right. The chickens and cows of the province of British Columbia produce nearly three billion kilograms of manure every year: about enough to fill a full-sized American football stadium to its top. And Abbotsford, with its 25,000 cows and nine million chickens, produced far more waste than the city of 160,000 people could handle. Much of it would get shipped to the prairies as fertilizer or, worse, dumped in abundance on local crops and nearby rivers, filling the soil, air and water with methane: a compound that, liter for liter, traps 80 times more heat in our atmosphere than the carbon dioxide puffing from our car exhausts. Cow waste would even trickle down the Abbotsford aquifer and flow downstream towards Washington State at a rate that made American farmers complain about their up-north neighbors. Abbotsford had a manure problem, and Bush wanted to deal with it.

He wondered if there was a way to make good use of all that manure. It was a prescient thought: recycling on-site farm waste would only become a more relevant global challenge in the 15 years to come. The nitrogen fertilizer used by many farmers then and now—the kind that tripled global grain production over the last 50 years—continues to dwindle in its supply, even before supplies from Russia became squeezed by the war. Couple a worldwide fertilizer shortage with a supply chain still wobbly from the pandemic, and you get expensive and scarce food for plants and, in consequence, smaller crop sizes.

Bush was fascinated by how some small farms fermented their manure and transformed it into fertilizer, all while capturing the methane in the waste and using it to power their homes. But many of these farms did so in isolation. He wondered if he could find a way to scale the transformation of manure into gas and fertilizer, to serve many farms at once.

The key to his dream was something called a biogas plant, which is a network of oxygen-free tanks called anaerobic digesters that take in manure and ferment it at nearly 40 degrees Celsius for three to four weeks. The process replicates what happens in a cow’s third stomach: the manure separates into solid and gas. When that happens in the stomach of a cow, it farts. A biogas plant, in contrast, turns that gas into usable fuel and funnels it into the power grid. And as a bonus: the solid that remains is odorless and can be used as fertilizer for crops.

I’d tell people I want to power the city with cow poop, and they’d look at me like I was a nutjob. — Christopher Bush

Some farms in British Columbia were using small biogas plants, and the technology was particularly strong in Europe. But to do this on a grander scale, he would need to build an industrial-sized biogas plant. The price tag: around $6 million. He needed to win over his neighbors, some of whom were worried about the smell or traffic. More than anything, though, he needed investors, but the idea was so new in the mid-aughts that there wasn’t even terminology for the kind of zero-carbon farming he was contemplating.

“Back then nobody had the sexy language,” says Bush. “I’d tell people I want to power the city with cow poop, and they’d look at me like I was a nutjob.”

Still, Bush could not shake the idea. So, in the wake of the 2008 recession, he sold the family home and moved with his wife, eight-year-old twin boys and six-year-old daughter to East Abbotsford. With the remaining equity from his house, his entire savings of $500,000, and $4 million in research grants and investor money that he finally tracked down, he built a farm and a biogas plant, with the goal of powering community homes with Abbotsford’s abundance of manure.

“We had planned another baby, but went for the anaerobic digester instead… we even had a picture of it next to those of the kids on our fridge,” he says. “We put everything into this.”

Bush’s initial results, especially for an ex-telecom specialist, were auspicious. It took him barely two years to build a working biogas plant, capture energy from cow droppings and convert it to electricity. In 2010, his plant became the first in North America to extract gas from cow manure and sell it to utility from a farm—the 126th plant on earth to do so, he says with a grin.

What would eventually make his plant special, he thought, was scale. Many biogas systems across the world already produced enough energy to sustain themselves. Bush had a grander idea: what if he eventually developed a biogas plant that could power an entire community? Arguably, no country needed this technology more than Canada, one of the top manure producing countries in the world, without a blueprint to dispose of it in an environmentally friendly way.

The investment was huge, but the finances appeared simple: he had to produce $2,500 of gas per day for six months to break even. Any profits would go toward funding his brainchild, the Catalyst Agri-Innovations Society: a consortium of people dedicated to advancing the environmental and economic sustainability of agriculture, hopefully one day based in a research and innovation center.

But his operation soon struggled: in the first 18 months, it averaged only $1,000 in profits per day. People were not buying the gas; machines would often break and need repair; and Bush, experimenting with cow, hog and chicken manure, was still far away from nailing the recipe for maximum gas production.

“Every month, I’d sell off a little more to my investor group to keep the plant going, and then when I ran out of shares to sell, I had to sell the plant. Financially, it was catastrophic for me… I was broken when it died.”

A former business partner bought the biogas plant from Bush in 2012, giving the then demoralized 40-year-old the chance to cleanly exit the farming world and start fresh. But Bush found himself unable to walk away from his goal: he figured his idea was the right one, but that it just needed better execution.

“I recognized I am an addict to this vision. I mean, I had already sold the house,” he says.

“It had become more important for me that the project worked than that economically I survived. We need this. The world needs this.”

Now, 15 years after reading the Popular Science Magazine sidebar, and ten years after losing much of his life’s savings, Bush remains at work, and the Catalyst Agri-Innovations Society is alive as a four-person operation.

On most days, Bush drives ten minutes westbound from the home he now rents with his wife to the Bakerview Farm Eco-dairy, a small dairy farm with a biogas plant that he and his team now use as a research headquarters. The parking lot there is full of families, gathered around the front-facing on-site ice cream shop.

“The front end is what pulls the people in. Us,” he says with a slight smile, “we work at the back end.”

Behind the ice cream shop is a modest-looking collection of barns engulfed in a scent of manure that penetrates even the hardened nostrils of any local Abbotsfordian. A blue-grey barn on the right houses 50 cows, each with a yellow name tag on their right ear. Colleen, Alexis, Daffodil and their contemporaries all face away from a dung-caked pit lined with a steel trough, which carries the fresh cow waste outside towards a network of bungalow-sized barns and trailers.

“You have to follow the poop to see the magic,” says Bush.

The eco-dairy is more eco than dairy: the buildings behind the cow barn hide the biggest active anaerobic digestion facility in all of Canada. Trailers propped up on two-foot stilts and packed with scientific equipment.

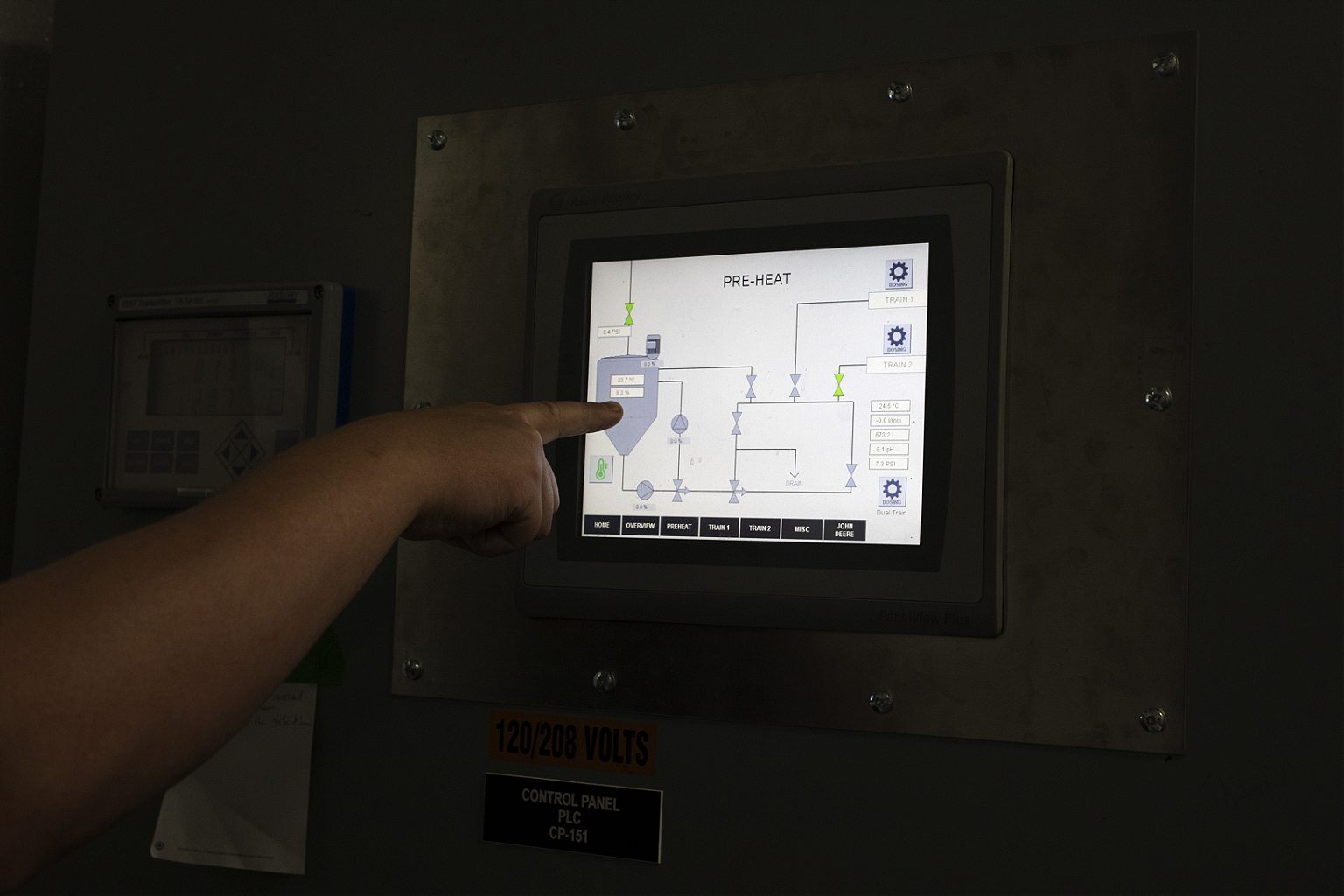

Those trailers contain $5M CAD ($3.8M USD) worth of equipment: 15 half-liter bottles connected to a chromatograph and monitor, eight 20-liter vats kept inside cupboards, two cylindrical 400-liter anaerobic digesters lining the walls, and six 1500-liter digesters kept inside a 38-degree fermentation room in the back. In its own barn is one big horizontal 85,000-liter digester that Bush calls Bertha.

Each container is filled with a fermenting, charcoal-colored manure mixture—roughly three parts cow, chicken and hog excrement, and one-part industrial food processing waste—Bush calls it poop soup.

The machines take 25 days to digest the mix and funnel its gas into the utility grid. Ultimately the gas powers 1000 homes and businesses across the province. The manure, meanwhile, after it gets stripped of its methane, becomes environmentally-friendly fertilizer for nearby crops.

Bush is no longer solo on his mission to make waste less wasteful: he has teamed up with James Irwin, a serial entrepreneur, bio-chemist and CEO of the agricultural research corporation Point 3 Biotech Corp. Before joining forces with Bush, Irwin used anaerobic digestion on microalgae to extract astaxanthin, an antioxidant with a red pigment that he yielded so purely it would sometimes come out as purple.

“A few people said, hey, you’re like the Walter White of Precision Agriculture,” says Irwin, “because of the blue meth, or whatever. I don’t know—I’ve never watched the show.”

Irwin had also used anaerobic digestion on microalgae to make biodiesel, and later to convert fats from agricultural waste into renewable natural gas. Bush wondered if the scientist’s expertise in collecting usable gas from organic materials would complement his own goals. So, they became business partners.

“Chris is the visionary at Catalyst, and I bring the research,” says Irwin. “He is building the car, and I’m assembling the pieces.”

The team expanded again in the last three years by hiring lab technician Travis Scott, and principal investigator Suman Adhikary, then a Concordia master’s graduate and previously a lecturer at Sonargaon University in Bangladesh. Adhikary’s job, complex in application, sounds simple in theory: create the best manure recipe for gas production.

“Now we try a bunch of recipes to put in the digesters,” says Adhikary. “Sometimes it’s half-chicken with 20 percent cow and hog. Sometimes it’s less chicken, because too much chicken manure produces enough ammonia to inhibit methane production. Sometimes it’s mostly cow… we’re still tinkering.”

Adhikary and the team iterate their mixture based on their own findings and the outcomes that emerge from European plants. Bush has traveled overseas to consult with his Swedish and German counterparts about their own mixtures of choice, and is closely following new work from Germany that uses green hydrogen to convert carbon dioxide into methane and increase the overall gas yield from digesters.

While Catalyst primarily uses the plant for research, it is still performing much better than Bush’s first iteration.

“It’s simple: more gas, more money, and this plant is making $5,000 a day,” he says.

“Financially, though, we still haven’t recovered from 2012.”

The final part of Bush’s vision requires a little collaboration with the neighbors. The team at Catalyst has an idea of converting their demonstrative research project into a community-scale manure management initiative, in which they would have large community biogas plants built to digest and ferment manure of several local farms. The plants would be co-owned: Catalyst would be responsible for their maintenance and upgrades, while the farmers would operate the machine. Bush figures such partnerships would be win-win-wins: farmers who face increasing pressure to restrict their environmental damage would receive professional help in mitigating their footprint, Catalyst would grow its business and, ultimately, Mother Nature would benefit, too.

“That way, farmers don’t have to go into it blindly and risk building a biogas plant by themselves—I know what that’s like,” says Bush. “Here, we’d both share the risk and the reward.”

It’s easy to get local farmers and businesses to buy into small-scale collaborations, like collecting grains from local breweries to feed cows, which Bush does regularly. But the bigger ideas, like powering your home with gas from animal waste, or convincing a farmer to build a multi-million-dollar anaerobic digester on their farm, tend not to be as easily adopted. Resistance to change is the biggest hurdle Bush’s ideas continue to face.

“When it comes to innovations in agriculture, the potential users need to be sure whatever is new is bulletproof before they make a move,” says Mike Manion, an executive in residence with agri-business accelerator IAFBC Agri business accelerator. “Change, without years of investigation and proof that it works, can make farmers fearful.”

But the province’s farming industry, according to experts, is in dire need of fixing. The Canadian federal government announced in July it was looking for ways to cut fertilizer emissions by 30 per cent by 2030. Local fertilizer is already running low. The pandemic and extreme weather of the last few years, which included record-breaking forest fires and destructive floods, compromised common supply chains with the prairies and California, and made fertilizer prices in the province skyrocket, says Lenore Newman, Director of the Food and Agriculture Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley.

“As a result, we’re in unprecedented territory in food loss in B.C. and in Canada: last winter, across the province, we had no lettuce on our shelves,” she says. “The only way we can ensure there is food security here is to produce domestically, more intensively and year-round.”

For those reasons, using local waste to grow more crops without spewing methane into the air could become paramount. Couple that with a provincial renewable gas subsidy program for B.C. residents to power their homes with biogas, and it would seem that the technology’s moment has arrived.

“At all levels of new farming tech, it takes that sort of government push to see progress,” says Manion.

“I keep trying to encourage Chris, because his ideas were about 15 years ahead of the curve, and now the environment is different out there… people just might start paying more attention to his work.”

Manion sees the immediate importance of in-house manure fermentation: making one’s own fertilizer can help protect against global supply issues. But there are still only three working digesters in all of B.C. For the technology to become mainstream, it must first become cheaper, and adopted by more trailblazers. If the research efforts at Catalyst lead to installing more industrial-sized, trusted, affordable biogas plants on nearby farms, it could open the floodgates.

“We need solutions to make home-grown fertilizer,” he says. “Agriculture is at a precipice—a turning point—and they might just be at the forefront of it.”

Thirty minutes inland from Abbotsford and the Bakerview eco-dairy, in the mountainside agricultural city of Chilliwack, is a massive construction site that is slowly developing the largest biogas plant in Canada. Once ready, the plant is expected to produce enough energy from manure to power approximately 4,000 homes, and also to recover nine million gallons of water per year from manure remnants via reverse osmosis and mineral rebalancing. Once operational, it will dwarf Bush’s research facility in gas production.

The $40-million CAD ($30.5M USD) project was just an idea in George Dick’s mind back in 2008, when the entrepreneur and dairy farmer at Dicklands Farms came across a magazine article about Bush’s own biogas project.

“I thought, where did this guy come from? We have the same idea!,” says Dick. “And he’s going through with it.”

Dick paid close attention to Bush’s trailblazing attempt to build a plant in the early 2010s, and witnessed the project’s first iteration bleed money and go out of business.

“I saw Chris fail… it was such a new technology and we knew even less about it then than we do now,” says Dick. “Someone had to take those first steps forward, even if they were risky.”

After a decade of research, fundraising and building, Dick is now months away from seeing his own years-long project come to life: the Dicklands Farms biogas plant is expected to be up and running by April 2023. If the plant functions as expected, it may be Dick, and not Bush, that will be remembered as the father of biogas in British Columbia, and possibly in Canada.

“The early bird gets the worm, but the second mouse gets the cheese,” says Bush. “Sometimes that’s the price of going first.”

But to Bush, a successful outcome at Dicklands Farms would feel like a win nonetheless. He wants he and his partners at Catalyst to pioneer research into biogas farming and scale their own operation, but more than anything, he wants his city’s manure problem to be solved. Whether he is the face of the movement, or the shoulders on which another innovator will stand, he longs to see the vision that pulled him away from his regular life materialize.

Besides, he says, the stakes are higher than personal glory.

“More than anything, this is about a mission: powering the world and solving one of the grand challenges of humanity,” he says.

“I’ll be the guy to lead it, or I’ll be a soldier on somebody else’s team. Either way, I’m calling this my life’s work.”

Any sustainable food game-changers on your radar? Nominate them for the Food Planet Prize.