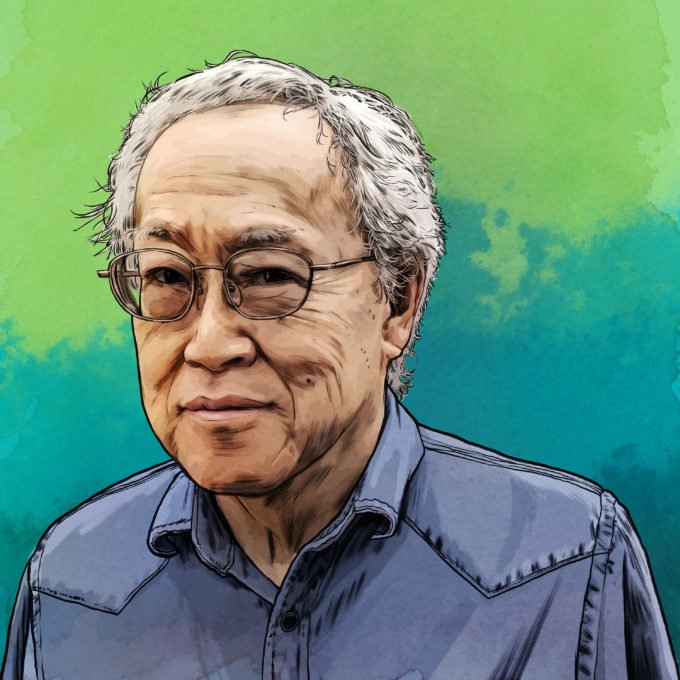

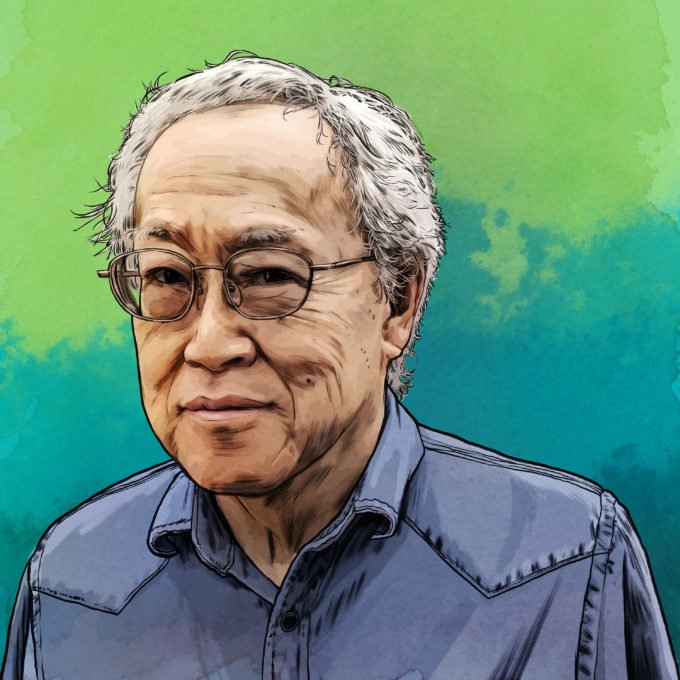

Yukio Iwamasa: Growing up in the Camps

Yukio Iwamasa spent half his childhood imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp. This is his story.

If you want to know the best thing about Gardena, in South Central Los Angeles, I’ll tell you. I think it’s Diana’s, a Mexican lunch counter with apocalyptically good machaca and fresh masa sold by the kilo. It’s especially good if you can meet Yukio Iwamasa there. Yukio, an artist and entrepreneur approaching his mid-80s, lives around the corner from Diana’s, in the house where he spent half his childhood, back when Gardena was a Japanese-American enclave filled with strawberry farms and Buddhist churches.

For this final episode from Los Angeles, though, I wanted to talk to Yukio about the other half of his childhood, the part where he and his family were imprisoned for being Japanese-Americans, locked away in Manzanar in the middle of the desert for four years during World War II. In its own grim way, it’s a distinctly American story. And it’s a personal story for me—Yukio is my father-in-law, the grandfather of my children. His testimony about life in the camps is important to hear—for them, for me, for any American who didn’t live through it.

The following is a condensed excerpt from our conversation. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: Let’s talk about before the war. You had grown up in Boyle Heights, right?

Yukio Iwamasa: Yeah, that would take me to the age of just after kindergarten, so that would’ve been first grade. My memory isn’t really substantial enough to tell you any stories about that except that I remember the FBI agents coming to our house one night dismantling the short-wave radio without asking for permission or anything else. It was a sudden intrusion that even I, as a kindergartner, recognized as a severe offense.

Thornburgh: So this was before the war, and Boyle Heights at that point was also kind of a mixed neighborhood. It was kind of Latino and Japanese-American.

Iwamasa: And Jewish.

Thornburgh: That’s right. So, you were around kindergarten and all of the pre-war hype and hysteria is really getting into full motion, and the first memory you have of what would eventually overtake your lives was FBI agents coming into your house?

Iwamasa: Often we get into conversations with other people, friends about what our first memories are and what they’re composed of, and that was one element that stands out.

Thornburgh: So that’s not just your first memory of the troubles and the incarceration and all of that. It’s one of your first memories of anything.

Iwamasa: Yeah. I find it difficult to separate and distinguish the two.

Thornburgh: That was your earliest childhood and marked completely by all of this stress and trauma of what was going on.

Iwamasa: Yeah. But that was right after Pearl Harbor, so it’s not pre-war, but the other [memory] is watching my folks sell off all of the household goods in one night, about five or six days prior to our evacuation. They sold off the car, the furniture, and everything else in the house. And I do remember the vultures that came to our house, knowing that we were stuck and we had to sell and clear off everything that we owned because our parents could only take what the could carry. You can imagine if you had to do that today in your house, or anybody else for that matter, no matter how rich or poor, where you’re having to dump everything, and your neighbors know this, and they’re offering you the lowest, lowest possible price for your valuable goods, your things that you hold dear. And for some reason, even though someone who is five or six years old is not really thinking about financial things, that was kind of a stand-out in my mind.

Thornburgh: You could tell that they were just getting endlessly screwed by their own neighbors, who knew exactly that they were in a vulnerable position, and therefore came to take all of the goods they could.

Iwamasa: Right. One of the things that occurred to me a little bit later on is when I heard about what the Jews went through in Germany when they were instructed by German soldiers to get on the train and that everything would be okay, and that they were being protected by this act. Those people accepted the word of the German soldiers got on the train. Whatever trepidations they may have had, at least they were trusting enough to get on the train, and the parallel that I find is that our parents didn’t have any guarantees that they were going to come back. They didn’t have any idea of how long they were going to be gone. They had no idea of whether the government would have evil intentions, and so there was, I think, a critical moment in time when that trust was passed on to the government. That was, I think, an exceedingly large decision that any person would make. You can imagine if you were told to get on a train right now today for your own good, that the government was doing this master plan to protect you from harm, and all you had to do was get on the train and they would take care of you, I don’t know if you could hand over that amount of trust.

I don’t know how many people would rebel and go into armed conflict. But our people very quietly went on the train, and they were not able to come back until four years later.

Our people very quietly went on the train, and they were not able to come back until four years later.

Thornburgh: None of these camps was a place you actually wanted to be, but Manzanar is a particularly infamous location. That’s the camp that you guys were sent to. Describe where it is, what it looks like.

Iwamasa: There’s a stretch of land, if you go skiing at Mammoth Mountain from Los Angeles, there’s a stretch of land prior to going up into the mountains on the low, flat plain, which is adjacent to Death Valley. There was, I think a B-24 bomber air strip on one side of the highway, and on this flat line, this just below Mount Whitney, really a desert with very, very little growth of sage brush. Anyway, they laid out barracks for about 10,000 people, and it was broken up into segments of 32 blocks, each having about 20 sub-barracks, and what we wound up in, our family, was a 20-by-20 foot space and we shared that with two families, or there were two families there, so in essence there were about eight people living in a 20-by-20 space for the first year or so. Meals were served three times a day on time and if you were late, you missed the meal. But one of the interesting things that happened in this arrangement is that during meal times, the families would not eat together. The kids would join their peers and leave their families because that was more fun for them, and the family structure started to fall apart because the father of the family didn’t have the control over his family. Kids were running off independent, on their own, being silly, or whatever, and playing.

So part of the family dynamics got a pretty good hit there, and so that, I think changed the way a lot of Japanese-American teenagers grew up due to that particular impact on their daily schedule. Small as it may seem, it was, I think, pretty significant.

Thornburgh: When I met your father, he was already quite old and he was not the figure that he used to be, but from everything that I’ve heard about him, from you and your brothers, this was an imposing person for whom this thing that you’re talking about—losing control of the family—must have been particularly challenging. I don’t know if that’s specific to your family or across Japanese-American families, but the whole thing seems an entire drama of powerlessness. On some level, that must hit the guys in a very specific way.

Iwamasa: Yeah, the concept of powerlessness pervades from top to bottom, from young to old. I can’t speak for him because he has his own legacy of being away from his father, who migrated to the US when he was a teen. He didn’t have a father figure or authority figure. But in my case, the psychological effect that it had on me is our people—Japanese-Americans—all those people that were in camp who look like me, were essentially powerless, without pride. Because if you think about slogans like, “Give me liberty or give me death,” and you watch all of the Hollywood movies about how heroes don’t kneel, but would rather fight and die than be subjugated.

The deep underlying psychological impression I got is that my people weren’t worthy, didn’t have the guts, and were inferior, lacking in moral courage.

That kind of underlying message or concept went completely against what we were experiencing ourselves as a people, so the bottom line assessment that I took—this is the deep underlying psychological impression—is that my people weren’t worthy, didn’t have the guts, and were inferior, lacking in moral courage. Maybe that was a sensible thing to do but it was not something to be proud of, to be going along with a really dirty, evil scheme. That we would do that just to survive…

Thornburgh: I mean, that’s brutal for that to be the way that you look around at yourself and your family. It’s painful to hear. I’m sorry.. I’m in full tears mode. It’s not for you to make me feel better but I think the combination of me knowing you as long as I have and having the love and respect that I do for you, and just to hear these things… we know the history, but I think there is a large part that’s missing when you really actually dig into it, and it’s one of the reasons why I was also a little hesitant to ask you to talk about this because I know this is not something that you talk about often.

Iwamasa: This doesn’t hurt me. It actually gives me incentive to recapture some of the things that are almost forgotten, even in my own mind almost forgotten.

Thornburgh: One of the things that I had heard about because you had mentioned being in a 20-by-20 barracks with two families, was that to this day there is a preserved cellar in one of those barracks at Manzanar Historic Site.

Iwamasa: That’s an interesting story. I don’t remember visiting the remains, but I do remember when the cellar was created. Our parents and a few other parents thought that it would be important and valuable for kids to retain literary capabilities in Japanese language, so they would be teaching the alphabet and some basic stories, but in essence, it was a grade school for first through fifth or sixth graders. The hitch was the government forbade teaching and promoting things in Japanese. There were specific regulations that would’ve gotten our parents arrested had the authorities found out that some parents were actually teaching, had the audacity and the nerve to teach Japanese language against the dictates of the government or the management.

Thornburgh: So these families got together and dug out a cellar by hand essentially in secrecy in order to create an environment where the kids could learn Japanese language because the adults would’ve been arrested if they were seen teaching them how to write and read Japanese.

Iwamasa: Right, so it was a subterranean room. I’m not sure how big it was, maybe 10-by-10, about that size. Essentially one small classroom that was hidden from the authorities.

Thornburgh: And this was underneath your barrack?

Iwamasa: Yeah, our barrack and the neighbor’s barrack. I was surprised to find out that the authorities somehow found it after we left and memorialized it. They’re maintaining it. I’d have to go and see for myself, but I’m been told that it’s been kept.

Between the camps and the draft, I spent ten years involuntarily in the care of a hostile government.

Thornburgh: That’s incredible. There’s not much that could speak more directly to the perseverance under those circumstances to dig out your own damn classroom in the desert sand and to do it under penalty of arrest.

Iwamasa: It took me a while even into middle age before I started to realize that there were other implications. Very subtle, profound, but hidden, that I had to do a little but of self psychoanalysis in order to understand some of these things that had impacted my psyche.

Thornburgh: Like what?

Yukio Iwamasa: The idea that a Japanese-American could become a world ranking scientist or a world ranking politician… that our ethnic group could produce the equivalent of the top minds in the world seemed [impossible]. The thing is, if you live among these people day to day, and we’ve all been leveled so that the top guys are making $22 a month and let’s say laborers are making $17 a month. There was nothing to distinguish or to exhibit the brain power or the the brilliance or the skills or the talents of these people. We were just generally flattened so that it was a gray mass of a really undistinguished people.

Thornburgh: How did you deal with that?

Iwamasa: I guess I accepted a lot of mediocrity in my life that I shouldn’t have. Someone should have kicked me in the ass and told me, “Hey, look higher,” because my mind has been distorted by that camp experience.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.