Three residents of Mexico City’s Casa Xochiquetzal talk about motherhood, love, loss, and freedom.

The big ochre house on the Plaza Torres Quintero, hidden away near the northern edge of Mexico City’s Centro Histórico, is filled with stories.

Not the stories of inquisitions and floods and ancient civilizations that stalk the area like ghosts, but the stories of 16 women, each a retired sex worker who has found herself without the support of family, without money, and, in many cases, without her health. Casa Xochiquetzal is named for the Aztec goddess of beauty and erotic love, and the women who live here face a triple taboo: they were sex workers, they’re poor, and they’re old.

Casa Xochiquetzal got its start in 2005 when a group of retired sex workers brought a proposal for the house to three well-known feminists: Marta Lamas, an anthropologist from the prestigious Universidad Autónoma de México; journalist Elena Poniatowska, and actress, singer, and playwright Jesusa Rodríguez.

Lamas, Poniatowska, and Rodriguez took that proposal on to then-Mayor (now President-elect) Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who allowed them to move into a space that had once been home to the Museo y Salón de la Fama, a gallery dedicated to Mexican sports and entertainment stars. Casa Xochiquetzal opened the following year.

I visited the house several times over the last few months, sitting on the sunny patio of the 18th-century house with women who were willing to share their stories.

Each woman’s story was unique. One spoke of her pets—stray dogs that had accompanied her through some of her most difficult times; the other spoke of poetry; another woman talked about her relationship with God and childhood memories. None of them spoke of the sex trade. Those are not the stories that define them.

The Dog Lover

Norma Ruiz—better known as Normota, or Big Norma—was born in 1953 in southeastern Mexico City, but grew up in Guadalajara. It was there, at the age of 20, that she met another of the house’s current residents. They would go together to cantinas and spend long nights out drinking beer, a habit that, over the years, led to alcoholism and addiction. Tall and outwardly cheerful, she describes herself as a strong woman, unafraid of death, despite a deep sadness that she’s been unable to fill ever since losing her mother at the age of five.

I have a recurring dream where I’m walking through a hole. On one side I see trees, on the other rocks, and in the distance a lot of water, but also dogs. I love dogs. I get to where they are and start to play with them.

There’s a park called San Fernando where I used to walk with my head down, sad, drinking wine, and this little dog, even if it was raining, wouldn’t leave my side.

One night I fed her and then decided to have a beer with a man in a car. The police arrested me and took me to jail, and I behind me, I could hear a lot of barking. It was my little dog who’d followed us all the way to the prison. The police officer turned me loose and said: ‘Take your dog and go.’ My dog kissed me and licked me—my little one, my Barbie. If it hadn’t been for her I would have been put away for 12 hours.

Someone killed my little dog. I found her still warm, with the noose they’d used to hang her. I stayed up all night [sometimes] drinking and [sometimes] not drinking and around four in the morning I dug a hole in the garden [in San Fernando]. I put her in a little sack and I put down flowers and that’s where my Barbie is. When I go to that park, she’s on one side and on the other mi Güero Bicicleta” (blonde bicycle), another dog that also loved me a lot. He had one blue eye and one white. I like to think I’m still with them.

The house has its rules. There are no pets allowed, for instance, not even for an animal-lover like Norma. The women share the household chores, taking turns to clean and cook meals for each other. Attendance at daily activities is mandatory, and the women make handicrafts—embroidery, dolls, papier-mâché—as a source of income.

The facility receives federal funding and oversight for hygiene and security. In addition to housing, public assistance covers each woman’s medical, psychological, and legal bills—there’s even money set aside for their funerals.

On one of the days I visited, it was Norma’s turn to cook: she made chicken with caramelized onions and rice, served with tall cups of pineapple juice. As we ate, the conversation turned to each woman’s homeland: Comalcalco in the southern state of Tabasco, Oaxaca, San Pedro de los Pinos right here in Mexico City—very different women with lives similarly shaped by their intensity, sometimes by loneliness, often by violence, and always by discrimination.

The Poet

Marbella Aguilar Sosa, 61, spends at least a few hours most days working at one of the many street stalls in this area that sell dolls dressed in voluminous, shiny gowns, and tulle wings. She’s sensitive—as quick to tears as she is to a gentle, affable smile—artistic, and loves the movies. She’s lived in the Centro Histórico for many years and knows it intimately.

As a child growing up in Mexico City, she says she was always misunderstood and regularly bullied. Despite her life’s hardships, she’s proud to have provided her children with a chance to study. She says her son is a university professor and her daughter is a teacher and accountant. A third daughter had hoped to become a lawyer, but died of leukemia at 18.

All of us here are common, everyday people who have suffered, cried, laughed, and, above all, lived through some very difficult things. But life is beautiful.

My happiest moment was when I wrapped my arms for the first time around my son. I felt complete, happy. The father [didn’t want me to have the baby], and told me ‘The kid or me—choose.’ I said, ‘I’m having this kid, you were only the sperm donor,’ and I fought for him, tooth and nail. I’m a feminist up to a point. I know that women have rights and that we should fight not to be ruled by a man. A woman can get her children ahead, even if that means working as a prostitute. There are too many women in this situation—women are honored until they’re 12, and from 12 on, if there’s not enough money, she knows how to make some, enough to feed her children.

They say there’s good to remedy the bad. I had to sell everything I had to treat my daughter’s leukemia and I would have done more. I don’t regret anything. I learned to cook, iron, sweep, dust, but I also like to study. I completed high school in San Ildefonso [a once-prestigious prep school.

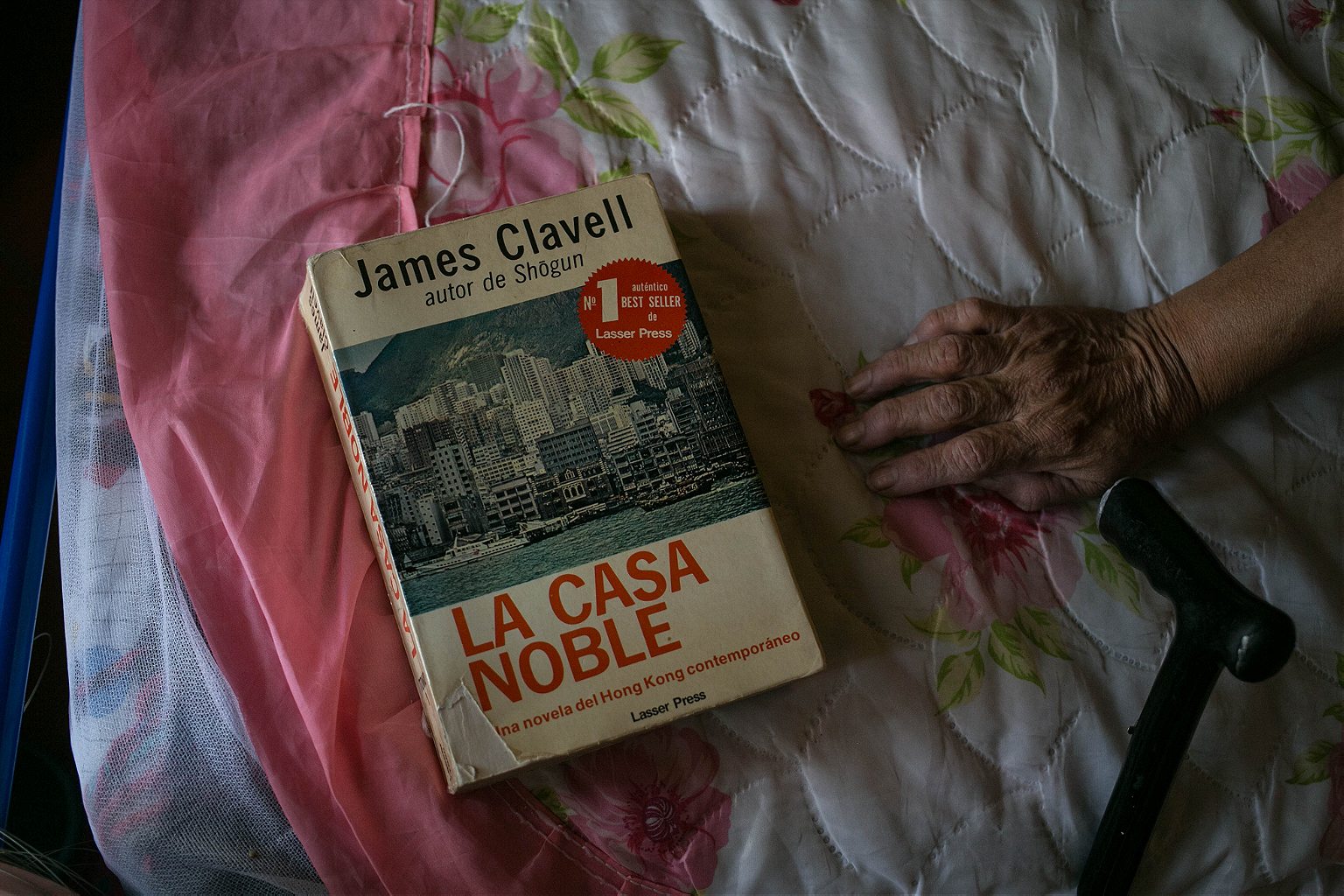

I prefer the company of a good book to watching television. I like the classics, like Cervantes, Tolstoy, and Rubén Darío. I’m fascinated by García Lorca.

I wrote a poem about sex work:

I am like a flower that grows in a swamp,

that everyone admires for her beauty and colors,

but nobody dares to touch

for fear of drowning in the silt that surrounds her.

In 2009, an organization called Semillas (Seeds) created the group Women of Xochiquetzal Fighting for Dignity, which continues to operate the house today. Despite the global media attention the house has received, it continues to face budget shortfalls. “Journalists come to take photos, to write articles, but most of them don’t come back,” says Jesica Vargas González, director of the house.

According to Vargas, in 2005, the city government awarded the women a 10-year, rent-free lease. Since that least ran out, she says, they’ve struggled to pay the bills. She and her four staffers regularly forgo their monthly salaries when funds are insufficient. During his presidential campaign, López Obrador traveled extensively throughout Mexico, but he has not returned to the Casa since its opening.

The Believer

On her 61st birthday in June, Juana Hernández Marcial, or Juanita, went out to buy fresh tortillas and then put on a figure-hugging red dress, to match her lips, and added a sunburst-shaped flower to her hair. Juana was born in the coastal state of Veracruz, recently became an evangelical Christian, and often breaks into song—particularly religious songs. She loves to tell stories from the Bible alongside stories from her own childhood: the two, at times, sometimes seem indistinguishable.

I have 35 pairs of shoes that my son sent me because he works at the [upscale department store] Palacio de Hierro but I don’t like this pair that much. They make me feel like all I’m missing is a broom to fly on, but he says they’re very nice. Things come to me from heaven, truly, after all I’ve suffered.

I came to Mexico City because my husband was a photographer. He was a travel agent, and he would leave the home drop the film and the cameras at the only pharmacy we had in the village. The years went by and the man kept coming. When we got married, he was 48 and I was 14. He was very handsome, Spanish, from Asturias. I saw him—God forgive me—as a kind of god. His car had these very thick wheels, and he carried two bottles of cognac, and he and my mother got drunk together and she said to me: ‘Okay, little girl, go with this man.’ I felt like I was in the clouds.

My husband would let me go out. He was a very good man. I loved to go to the disco. We had a person in the house who helped with the cleaning. He was gay and he loved to go around with me. I was an attractive girl, nice body, and he loved to brag about me with his friends, his boyfriends. We would go to the Zona Rosa (Mexico City’s gay district) where it was all gays, but I would have such a good time because I was like a doll, a little girl, only 16 years old.

I’m now getting ready to finish my studies in theology. I only have another eight months after three years of study, of staying up all night, of going hungry, of moving around by bus and metro. From the time I was a little girl I remember I’ve been inclined toward religion.

God loves everyone equally, gays and sex workers and thieves. He doesn’t want the sinner to die, he wants the sin to die. And the sex worker isn’t a sinner. I love and forgive everyone. I pray every day. I pray for the whole world. For the prostitutes and the gays and prisoners and people in the hospital and above all for the government so that God may guide them.