Coffee can be ground by machines. Soups can be blended in a processor. But rotis should always be made by hand.

Twice a week or so for the past few months, I’ve returned home to my flat in London and switched on a large machine that rests on a counter top next to my gas hob. Minutes later, soft, warm, and perfectly round roti glides silently out in the bottom tray.

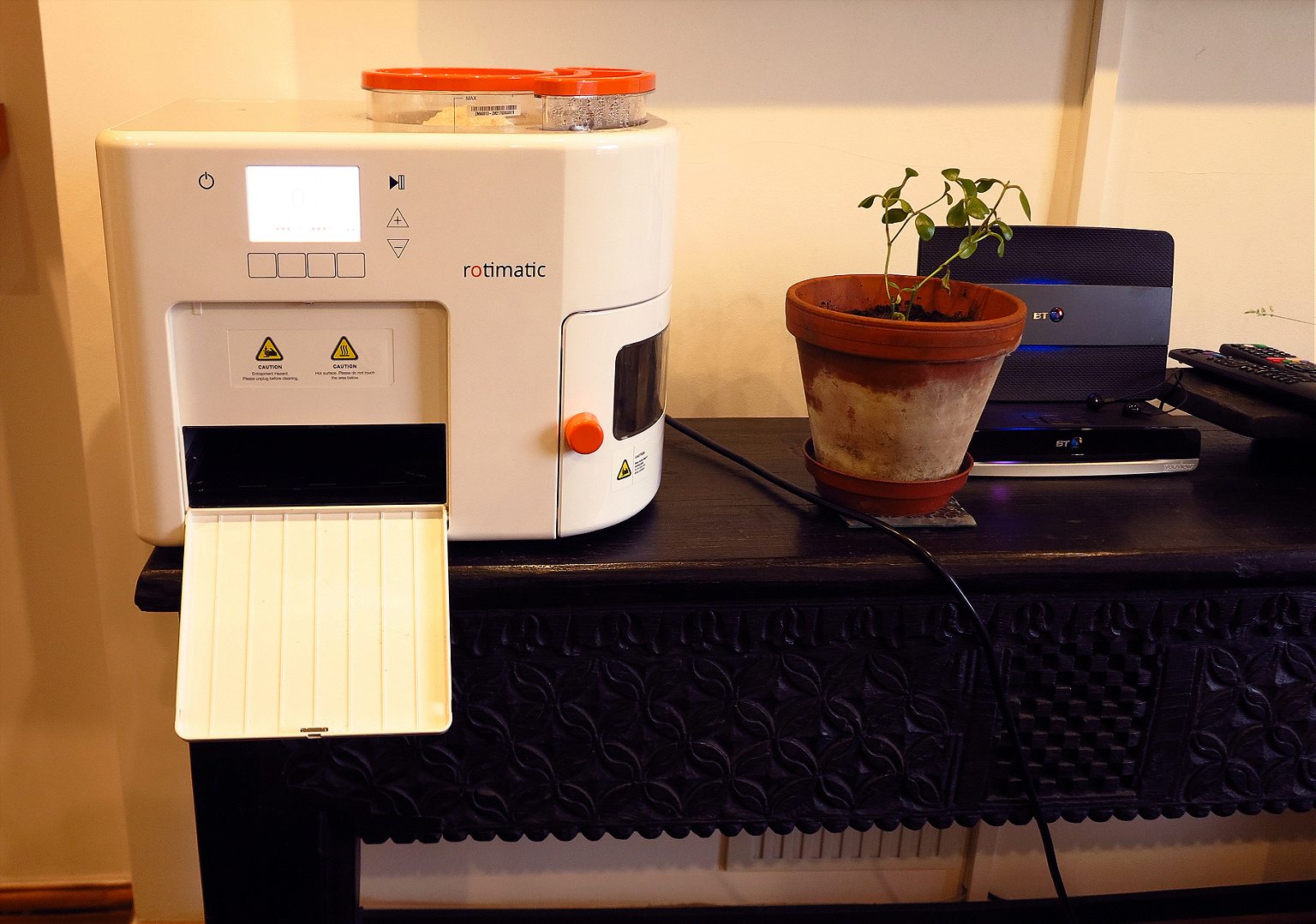

Last year, I’d decided to borrow a “Rotimatic,” the latest appliance that added to the soundtrack in my kitchen, accompanying the humming refrigerator, the ping of my microwave, and the crescendoing dishwasher during its rinse and drain cycles.

The Rotimatic, which took eight years to develop, made its first appearance on the market in the early summer of 2017 with a luxurious price tag of US$999. Bulky and white, around the same size of a large microwave, it weighs about 44 lbs and plainly contradicts the notion that the devices of the future will be smaller and more aesthetically pleasing than those of the present.

First-time users are asked to download an app and connect the internet-enabled machine to the web (the machine is self-learning and, over time, can adjust to different flours and oils). It also produces an impeccable—if small—roti with just slightly more effort than it takes to charge a cell phone.

Once switched on, the Rotimatic grunts and whirs loudly for six minutes as it warms up. The robot feeds a small amount of flour, water, and oil, housed in three separate containers, into a mixing chamber. The ingredients are rolled into a perfectly circular pellet of dough, flattened into a disc the size of my hand, and cooked in an oven. The finished product glides silently out in a tray like a letterbox.

Under optimal conditions, a Rotimatic can roll out one roti every two minutes, though, in reality, the combination of a clogged flour pump, too-sticky dough, or an insufficiently round pellet can derail the entire process. When that happens, an alarm like a smoke detector goes off and the display flashes an alert. The effect on users is to first instill a sense of bemusement, quickly followed by mild annoyance on realizing the Rotimatic adds to an ever increasing list of smart gadgets that already emit alarms or alerts. Isaac Asimov may have been describing a Rotimatic when he wrote in 1964 that “robots will neither be common nor very good in 2014, but they will be in existence.”

***

My father left Pakistan for Scotland in 1962; my mother followed a decade later. In my home in Glasgow in the 1980s, rotis were as ubiquitous as bottles of Irn Bru and fish suppers. Our fridge always contained a metal bowl with some freshly prepared dough wrapped in clingfilm. I could judge its age by the darkening color of its edges, where my mother’s hands had pulled out a piece to use for dinner. I knew it was fresh when I could see her fingerprints on the dough’s surface.

If she was in a good mood, she would turn the roti into a phulkah, flipping it out of the tawa—a concave frying pan ubiquitous in South Asian kitchens—and throwing it on an open flame, where it would blow up to the size of a small balloon. As a teenager, I knew if I wanted a snack, there was always a roti to be found, wrapped in a tea towel in a basket on the counter. When visitors came over, they were asked not if they had eaten lunch or dinner, but “Roti kha li?” (Have you had roti?).

The humble roti, also called a chapati, is the primary staple starch for hundreds of millions of Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis, consumed, in one form or another, at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Rolled into layers and shallow fried with ghee or oil, the roti becomes a paratha, served as a hearty breakfast with spiced eggs, fiery pickles and cool, sour yogurt. Deep fried, the roti becomes a decadent puri, golden and light and filled with a cloud of steam.

Billions of rotis are packed into metal tiffin carriers and dispatched to workplaces throughout the sub-continent every day, where they’re eaten with pickles and simple dishes of stewed or dry-fried vegetables. In the evenings, street markets in cities like Lahore and Ahmedabad are busy with street vendors pulling tandoori rotis from the guts of clay ovens, or rolling out immense, delicate rumali rotis, made from a mixture of atta (wheat flour) and more elastic maida (or refined flour, introduced from Central Asia with the arrival of Islam in the 12th century), and cooking them on a broad iron dome heated with coals. Any wedding or temple meal will invariably end with guests using flatbread—be it leavened naan or stacks of simple rotis—to marshal food around their plates and wipe up the last remaining drops of gravy.

Rotis have also played their part in the political life of the Subcontinent. In the months preceding the Uprising of 1857—an event known in British history as the Sepoy Mutiny, and in India as the First War for Independence—the mysterious distribution of rotis by an elaborate network of watchman and couriers spooked the paranoid British. More than a century later in 1970, when the socialist candidate Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto ran for election in Pakistan, his campaign slogan promised “Roti, kapada aur makaan” (food, clothing, and shelter) for all. Four years later, a popular film of the same name flatly blamed prime minister Indira Gandhi for the hunger, joblessness, and graft that gripped India.

By then, rotis had long since made their way out of South Asia and into the diets of any place with an Indian diaspora, from Singapore to Dubai to Trinidad. The 1.5 million soldiers of the Indian army that served the British empire in Europe, Asia, and Africa during World War I received rations of flour, which they cooked into rotis using mess tins suspended over small fires. In 1916, the 129th Baluchis regiment in Rangoon briefly went on strike when rations of flour ran out. During the Blitz, evacuees from London were sheltered in the Scottish port of Nairn where Indian soldiers fed them rotis, naan, and curry, a style of cooking that had been introduced to the British isles well over a century earlier. The redirection of natural resources from India to feed frontline British troops during World War II also contributed to the famine that devastated the state of Bengal from 1943-44 when over 2.1 million people died due to starvation and disease.

For a generation of South Asian men who came alone to the UK in the ‘40s and ‘50s after the cataclysms of war and empire, South Asian food was initially hard to find.

For a generation of South Asian men who came alone to the UK in the ‘40s and ‘50s after the cataclysms of war and empire, South Asian food was initially hard to find. Groups of men who had never used a stove found themselves sharing houses or apartments. They almost always sought a flatmate who could prepare a meal. He would be given a discount on rent if he agreed to prepare rotis and curries for dinner each evening.

My father was 16 when he arrived in Glasgow, the city that built the ships that fed the British empire. He returned to Pakistan every few years for a break and taste of home. On one such trip, he met and married my mother who had grown up in a succession of colonial homes maintained by cooks, domestic helpers, and gardeners. She arrived in Glasgow in 1970, unable to make so much as an omelet. My father taught her how to make rotis and curries. Two years later, I was born in the working-class neighborhood of Pollockshields.

In the late 1980s, my grandfather came to live with us for the last ten years of his life. After the partition of India in 1947, he had spent his adult life in my father’s town, Mian Channu, northeast of Multan, in central Pakistan. A simple man who enjoyed cinema and music, his demands were equally modest. He was also eccentric; he wore a Turkish fez and a cravat. “Mujhe bus ek tuk chahiay” (All I need is one roti), he would say, holding out one open palm.

***

I moved to London after graduation in 1997 to pursue a career in journalism. In 2008, I moved to the Gulf region of the Middle East for seven years, arriving in Abu Dhabi, where I helped launch a daily newspaper, and later moving to Doha, where I worked for Al Jazeera. Abu Dhabi and Doha, major cities in oil-rich Gulf states, are home to millions of Filipinos, Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis who work as day laborers on construction sites, in retail, and as domestic help, often in harsh conditions where unscrupulous and unregulated employers hold their passports to keep them from leaving. They are transported from their poor, ramshackle neighborhoods into futuristic city centers each morning to work eight-hour shifts in residential areas like The Pearl in Doha (“The most glamorous address in the Middle East”) or museums like the Louvre Abu Dhabi (“See Humanity in a new light”). On hot summer evenings, when the humid air is still, workers can be heard late into the night, drilling, sawing and hammering stubborn pieces of steel into place.

In Doha, where foreigners overwhelmingly outnumber citizens, Germans went hunting for chocolates by Baker’s or Nussbeiser’s, Filipinos traded cans of Red Horse beer, Jordanians obsessed about kanafah, and Brits complained about the lack of English bacon. Here, South Asians generally have an easier time finding the flavors of home. Most of the time, I would meet friends for dinner in Msheireb, an old neighborhood of narrow streets lined with mosques and cheap barbers situated behind the city’s oldest souq. From Msheireb’s tangle of old, low-rise buildings, Doha’s glass and steel skyscrapers resembled a distant utopia.

On Friday evenings, hundreds of Qatar’s construction workers visit Msheirib after midday prayers and sit on strips of grass or pavements, drinking spiced tea for one riyal (25 cents). Many eat parathas (25 cents) stuffed with cheese, smearing them with sugar or honey to make a simple dessert. At Lamazani restaurant, I would sit on plastic chairs and eat freshly made roti and chicken kebabs next to the shop that sold the chickens, alive. At a restaurant called Khosh Kebab, I asked the owner if the kitchen could prepare something for a vegetarian friend. He impatiently told me they served only kebabs and rotis. “If you want anything else,” he told me, “go somewhere else.”

Finding good rotis is not quite so easy in the West, and time constraints mean young British South Asians now rarely cook them at home. Like pizza dough and ready-to-bake puff pastry, roti, parathas, and naan have been staples of frozen foods aisles in South Asian grocers and British supermarkets for at least a decade. Brands like Taj Foods and Shana Foods sell rotis and parathas assembled in India and shipped to the UK. Young British South Asians once mopped up their curries with white bread. Now they open their freezers and reach for packets from Nishaan and Ashoka.

In the last decade we’ve grown accustomed to admiring handmade strips of tagliatelle emerging from chrome-plated pasta makers or rustic loaves of focaccia emerging from the oven, the color of dusty soil, drenched in sea salt and olive oil, aromatic with rosemary. Yet even with the recent appearance of Indian fine dining in cities like London and New York, roti is still just something your mother makes with an old metal bowl, a rolling pin, and a frying pan blackened with use. On South Asian cooking shows, chefs grind spices and fuss over curries. No one rolls dough into rotis. In South Asian restaurants, rotis are often cruelly found at the bottom of the menu. Bread and pasta have gone gourmet, but cooking roti is still unjustly viewed as an act as simple as pouring a glass of water.

By offering convenience and automation, the Rotimatic won’t dispel the notion that anyone can cook a flatbread. While the machine has enough settings to cater to individual tastes, each roti emerges with the same size and consistency. Coffee can be ground by machines. Soups can be blended in a processor. Breads should always be made by hand. I imagine many Rotimatics will end up in cupboards already filled with unwanted bread-makers.

On a recent evening, I stood contemplating what to eat for dinner and started to fill the Rotimatic’s chambers. Instead, I dumped the flour in a metal bowl and added water and salt. I rolled the dough into a misshapen square and cooked it in a frying pan. When I was finished, my kitchen counter was smeared with flour and the roti was dense at one end, tissue thin at the other. I lowered it onto an open flame and watched it slowly expand. I ate half, wrapped the remainder into a tea towel, and placed it in a basket on the dining table.