Dy Proeung built scale models of temples. When the Khmer Rouge took over, he had to hide his life’s work—and his identity.

Thousands of tourists flock to Siem Reap every day to visit Angkor Wat, piling into the temple complex with their cameras at the ready.

But down a quiet side-street in the center of town, there is a very different scene. Here, Cambodian architectural draftsman Dy Proeung lives with his daughter in a quiet, dusty house, its garden littered with miniature sculptures of the imposing temples tourists come to see.

At 82, he finds it increasingly hard to care for his miniatures and without adequate funding for repairs or restorations, they have fallen into disrepair. Exposed to the elements in his courtyard, they have gradually lost their details, eroding with time, rotting in the rain and cracking in the sun as tourists trickle in to see them for just $1.50.

But for Proeung, they are still treasures. He cuts a tiny figure, walking among his work in worn plastic sandals, his slim, sun-browned face cracking occasionally into a kind smile. To him, these sculptures are a reminder of an extraordinary life, a hard-won relic from a time when art flourished in Cambodia—before the Khmer Rouge installed a regime that made Proeung, as an artist and intellectual, a target for killing.

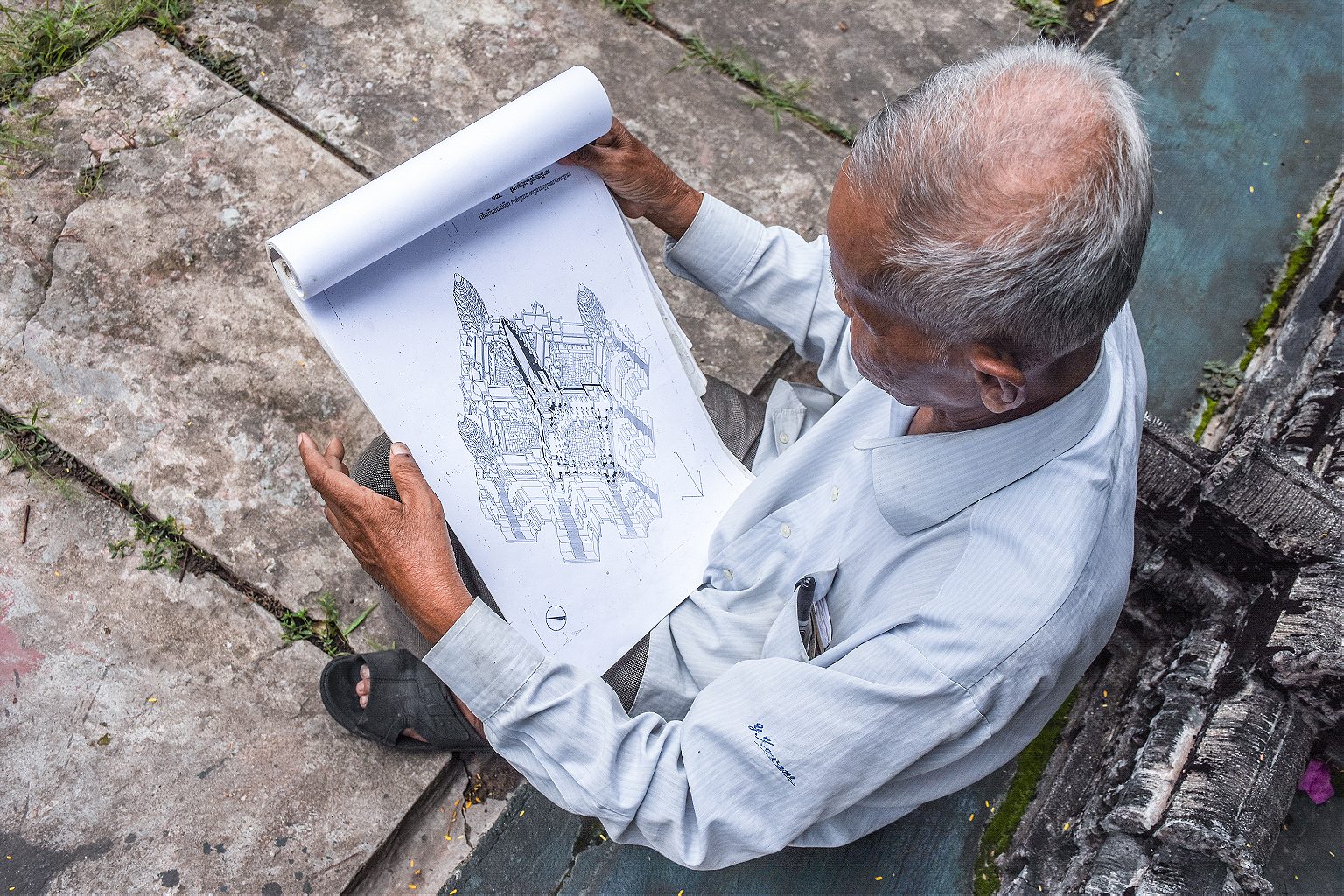

Before the Khmer Rouge, Dy Proeung worked as a draftsman for Conservation d’Ankor, a branch of the French research institute Ecole Francaise D’Extreme Orient (EFEO) designed to safeguard Cambodia’s temples.

He had always felt a pull towards the arts. Growing up in Phnom Penh—Cambodia’s capital, economic hub, and center of creative activity—Dy Proeng had dreamed of building.

“I wanted to be an architect even when I was a young boy,” he told me, taking a seat on a wooden cot under a sun-bleached tarpaulin and gesturing for me to join him.“Then as I grew up and learned more about Khmer architecture, I felt inspired to learn.”

After high school, he enrolled in the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh. He graduated in 1960 at the top of his class.

His copy of this book would become his greatest threat and greatest treasure in the years to come.

From 1967 to 1969, while on contract with Conservation d’Ankor, Dy Proeng lived in Siem Reap, the small town that has since become the center of Cambodia’s tourism industry. In those years, Dy Proeung was one of twenty draftsmen working at the organization’s survey office, directed by two French architects, Guy Nafilyan and Jacques Dumarcay.

“I felt in my heart that my work was not coming from me, like I was just a vehicle for it,” he says. “I believe I was reincarnated… born at the same time as Angkor Wat was built and reincarnated over history to work with the temples. My passion is very old.”

Between Independence in 1953 and the rise of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, Cambodia’s arts scene flourished. Dy Proeung was just one of many passionate creatives drawn in those days to exploring Cambodian identity through the culture of the ancient Khmer dynasties.

Khmer rock and roll became popular, new art galleries displaying modern paintings and sculptures filled with references to traditional Khmer motifs popped up in Phnom Penh, local fashion blended contemporary western design with Khmer tradition, and the New Khmer Architecture movement, spearheaded by celebrated architect Vann Molyvann, dusted the country with progressive buildings, characterized by the innovative use of materials, attention to airflow and shade, sparing use of ornamentation, and visual and structural references to traditional Cambodian construction techniques. Like many nations emerging into the post-colonial world, Cambodian architects looked turned toward the international avant garde to inform their reinterpretation of an ancient past.

Dy Proeung’s most significant work at the time was his involvement in the restoration at Angkor Wat. He worked with four other draftsmen and a team of specialists on a detailed survey of the temple complex, drawing architectural floor plans and elevations, the results of which were recorded in a book of monographs published by Guy Nafilyan in 1969.

His copy of this book would become his greatest threat and greatest treasure in the years to come.

The Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), or “Khmer Rouge,” rose to power in the early 1970s. They first emerged as a counterweight to the capitalist, US-backed Khmer Republic Regime, which had overthrown the monarchy installed by King Sihanouk following Cambodia’s independence from France. By 1973 they controlled 85 percent of the country. Two years later, they took Phom Penh and controlled it all. The regime immediately set its sights on the quick and systematic destruction of Cambodia’s burgeoning creative culture.

Within days of taking power, the new regime forced millions of people from the cities into rural labor camps. Over the years, millions more lost their lives and much of Cambodia’s cultural heritage was destroyed. Cambodian architecture also suffered, with many ancient buildings falling into disrepair or destroyed during regime-led raids for resources.

Religious sites and historical treasures were wrecked as the slaughter spun out of control. The Khmer Rouge dubbed 1975 as “Year Zero” and set about constructing a rural, classless society, transforming Cambodia into a nation of traditional rural peasants, referred to as the “old people.” Intellectuals, artists, and elites were seen as “new people,” an impure threat to communist control.

Dy Proeng knew that, given his education and work, he would have no chance of survival under the new regime. Shortly after the Khmer Rouge rose to power, he set about hiding his identity.

“Some of the soldiers had been watching me, climbing up in the trees near my house and looking over the walls,” he says. “I knew the Party would probably come to my home to raid it eventually, so one night I took all my drawings and architectural documents and buried them far from the house.”

Rather than destroy his life’s work, he hid every piece of evidence of his past in the ground, sneaking out in the dead of the night. Had he worked in the daytime he would have be caught.

“In the end they never came to interrogate me so I was lucky. I knew that if they had come, and if I had not had the chance to bury my work, they would have slit my throat,” he tells me, stopping to draw his thumb across his neck like the blade of a knife. “Like this, with the sharp edge of a palm branch.”

I was never scared because I had this secret to keep me going

Their biggest secret hidden, Proeung and his family became farmers for the Pol Pot regime. Like all other Cambodians in those years, they were put to work, made to wear the same black costume, and forced to renounce all money, schooling, private property, religion, and any sense of individual identity, which included all forms of culture beyond the strictly enforced notions of “purity” imposed by the state. Even children were forced to labor in the fields or become soldiers.

Working conditions were harsh, hours long, and punishments for failing to comply were extreme.

Once, tasked to look after cows in a field near his house, Proeung’s attention wandered. One of his charges strayed into a party-owned field and started eating the crops. The local Khmer Rouge soldiers arrested Proeung, but before he could be punished, his brother-in-law—a doctor forced to work under the regime in another part of the country—found out about his arrest and intervened on his behalf.

“Usually, if this happens the person responsible will be arrested for punishment or executed. But I was lucky,” he said. “During the Khmer Rouge, you could get in trouble for anything because they just wanted to kill. “If I had done something seriously wrong, no-one could have saved me.”

Despite those horrors, Proeung does not remember feeling frightened during the four years of Khmer Rouge rule.“Because of my passion for art I felt very strong inside,” he says. “I was never scared because I had this secret to keep me going.”

When Pol Pot’s regime fell toppled in January 1979, Proeung dug up his book and his drawings, his photos and memories, and got to work. He had survived one of the most notorious genocides in history. Most of his fellow architects had not been so lucky.

An estimated 1.7 million Cambodians lost their lives under the Khmer Rouge, many of them intellectuals, professionals, artists, and allies or employees of the old regime. This amounts to almost one in five people living in Cambodia at the time.

With the fall of the regime, Proeung took on a new role as a chief within his community, overseeing infrastructure development and guiding major decisions within the community. For three years he juggled his ill-paid public role with his old occupation, developing drawings and plans from the survey work that occupied his time prior to the Khmer Rouge.

Using the plans he’d buried years before, he started miniature reconstructions of all four temples–Angkor Wat, Bayon, Ta Keo, and Bantaey Srey–that he had worked on in what by then felt like a previous life. The process took him six years.

“I made these because I wanted to preserve my knowledge for the next generation of Cambodians,” says Proeung.

The to-scale models each spanned several square meters and varied in height according to their life-size equivalents, as low as 30 centimeters (12 inches) tall in some places, more than a meter (3.2 feet) in others. He painstakingly designed each structure using cement and giant hand-made moulds, most of them now crumbling and moss-covered at the back of his garden.

Not long after finishing his sculptures in 1994—the culmination of years of secrets and careful planning—a British soldier came to his home to ask about his work as an architectural draftsman, which he’d heard about through the grapevine. Once at Dy Proeng’s house, he saw the sculptures. The soldier eventually introduced Dy Proeng to King Sihanouk, the monarch who had governed immediately after independence (he was later exiled to Beijing, where he died in 2012). Together, they helped Dy Proeng organize an exhibition in Phnom Penh.

“I felt such a deep feeling when [he] talked to me,” he remembers. “So excited and happy… I always dreamt that I would meet him [one day] and my dream became true.”

Proeung ended up making a gift of the Angkor Wat miniature to King Sihanouk for his birthday. Impressed by his work, the King personally requested that he pass on his knowledge to the next generation of Cambodians.

“Since that time, I have been teaching according to what the King asked me to do,” says Proeung. “He advised for the young boys and girls to try to learn traditional architecture because this is the culture of Cambodia, it has to continue to be passed down. It is our heritage.”

Thirty years after he first started making his miniatures, Dy Proeng is still teaching and creating small sculptures and reliefs of Siem Reap’s temple complexes to sell to travelers passing through.

He smiles, taking one of the carvings in his gnarled hands. “It was my destiny to do this job.”