One man keeps an ancient Islamic tradition alive in Brooklyn.

It’s 2 a.m. on a Saturday night when Mr. Muhammad Boota’s alarm goes off. As late-night revelers around New York shuffle home after last call at the bar, Boota is just getting started. He puts on a green shalwar kameez, ironed fastidiously by one of his daughters. Gold-lacquered vest? Check. Matching turban? Check. Dhol, the double-headed drum of his native Punjab? Check. A fifteen-minute drive in his Honda Civic takes Boota from his home in Coney Island to Foster Avenue in Midwood. He parks near the Makki Mosque and starts drumming.

For more than two decades, Boota has roamed the streets of Brooklyn during Ramadan, the Islamic holy month of daily fasting. Moving between various Muslim-dense neighborhoods, he marks the wake-up time for the pre-dawn meal that commences the fast. For fifteen minutes, he enlivens the footpaths of Foster Avenue with thumping drumbeats that he learned as a child, rendering New York the rather bewildered site of a tradition that spans the Muslim world, from Cairo to Kashmir.

In a religion that mandates five daily prayers, the role of the announcer has always been a central one. The tradition begins with Bilal ibn Rabah, Islam’s first muezzin, who called the earliest Muslims to prayer in the streets of Medina. The call to prayer (aadhan) has since flourished as an auditory rhythm of life in the Muslim world, marking the five times for worship everyday. Many visitors unfamiliar with the phenomenon find the recitation beautiful, almost ethereal. For Muslims living abroad, there are few sounds that can so swiftly transport them home.

During Ramadan, however, there is a need for an additional announcement that says, “Let’s eat!” instead of “Let’s pray!” Before the Islamic fast begins at dawn, believers are encouraged to wake up and have a meal to help them make it through the day without food. Given the more indulgent nature of this call, those who announce it, the musaharatis, have a more playful role than that of the muezzin. The daily call to prayer is announced from inside the mosque, wafting disembodied from the towers. It is a simple recitation, unaccompanied by music. The musaharatis, however, roam the streets armed with drums and tambourines. In Turkey, they wear Ottoman costumes. In South Asia, they are called sehar-khwans. They use dhols, larger and more sonorous than other drums. Some, like Boota, dress in an unmissable neon green.

“I’m not fasting,” he tells me in the evening, when I ask him what he would like to eat to break his fast. I am visiting him at his home in Coney Island for iftar, the evening Ramadan feast. His family has filled up a coffee table in the living room with enough food to feed twenty people; as it turns out, it’s just for the two of us. Boota tells me that his interest in drumming for Ramadan is not evangelical, but simply musical. “I came here [to the U.S.] because of music. I come from a family of drummers: my father and before him, my grandfather.”

Drumming at dawn is a very small part of Boota’s musical portfolio. He came from Pakistan to New York in 1992 as part of an entourage for the Brooklyn Mela, an annual summer festival in Midwood that celebrates Pakistan’s Independence Day. He stayed on, and has since performed at hundreds of festivals, weddings, showers, and more. He appears to be the Pakistani-American community’s go-to guy for injecting beloved kitsch to any celebration. And it’s not just the Pakistanis. “My Indian and Bengali fans love me even more!”

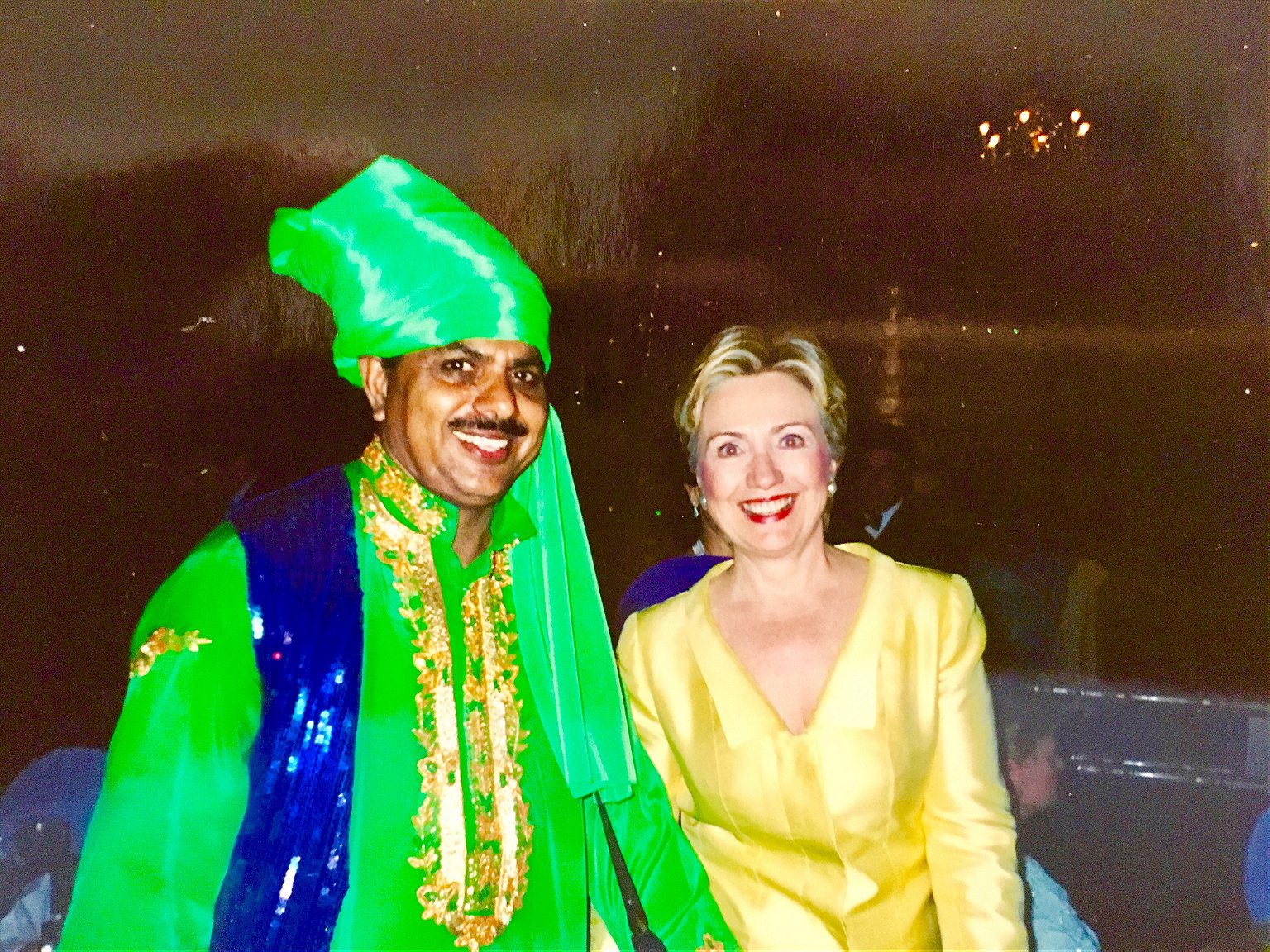

Soon, Boota’s domain stretched from the communal to the diplomatic. He’s performed at VIP events. He was invited to Washington, D.C. several times to receive Pakistani heads of state. Musharraf, Nawaz Sharif, Asif Zardari: name any relevant politician hailing from the motherland, and chances are Boota can furbish a photo from his iPhone of him shaking hands with them. My favorite one is of him with Hillary Clinton; it’s hard to tell who looks happier.

Drum aside, Boota is the classic immigrant; he hustled. Over the years, he has paid his dues in construction, working at gas pumps and as a security guard. He drove limousines for fifteen years. For a decade, he lived away from his family, sending money home and visiting whenever he could. Today, he lives with them on Coney Island: Boota, his wife, and his eight children. He impresses upon me his achievement using a metric of success often employed by immigrants: the earning potential of his offspring. “Two of my daughters are lawyers, another one is a dermatologist. My son’s an engineer.”

In many ways, Boota is now the well-settled achiever of the American Dream, sitting in a house that he owns, surrounded by successful children that still defer to him when he calls out. “I sometimes think I never left Pakistan,” he tells me. “We eat the same food, we speak the same language; everything is just the way it was.” His son brings in water for me and his daughters regularly pass by to check if their father wants anything else to eat. A dozen grandchildren run and scream in the front yard, likely on a communal sugar high from the fruit chaat and juices served during iftar. Forget the white picket fence and 2.5 kids. A house by the beach on Coney Island and eight well-mannered children is what Boota’s talking about.

He has learned to restrict himself to a handful of neighborhoods that are almost exclusively Muslim

I am curious how he has managed, for twenty years, to drum away in New York before the crack of dawn. Big cities are remarkable in how much strange behavior they let their residents get away with, but a pre-dawn session with the dhol seems like pushing the envelope. I ask Boota if he has run into issues. He tells me that he has learned, over time, to restrict himself to a handful of neighborhoods that are almost exclusively Muslim. He has also lowered the frequency of his excursions. He doesn’t follow a strict schedule, but drums, on average, two times a week during Ramadan. And for every detractor and noise complainant, there seem to be a dozen who admire the role he plays in their small community. “People appreciate it,” he tells me, “ because this is a part of our culture that no one knows about.”

The tradition is indeed an oddly well-kept secret. Even as a Muslim, I only learned of it this Ramadan and began searching for stories from around the world; of the Christian musaharati waking up his Muslim neighbors in Acre: the two thousand Turks that roam the streets of Istanbul during Ramadan: and our very own Boota, chronicled by the New York Times in 2010. You can even buy a remarkable children’s storybook telling the story of Najma, a young Istanbulite who wants to be the world’s first female musaharati. The Amazon blurb for the book asks, “Will [Najma] have what it takes to be the drummer girl of her dreams?”

Traditions are frequently our attempts to romanticize the banalities of yesterday. The practical becomes the whimsical. In Istanbul, the drummers are partly incentivized by a need to make up for lost income since very few people schedule Ramadan weddings, their major source of income during the rest of the year. In Boota’s native Pakistan, the tradition gained ground mainly in small villages, where loudspeakers and sirens did not appear until a few decades ago. People in Punjabi towns like Talagang still remember a time when the Ramadan drummer was as essential to the fast as the guy who delivered water to each household.

But the prosaic origin of a tradition doesn’t make it any less special. Salted cod, a beloved Mediterranean staple, was the practical invention of a pre-lapsarian world where people had not yet nailed down the mechanics of refrigeration. Tell that to my husband’s Portuguese family, and they’ll grace you with one offended look before going back to eating their bacalhau. And so, although everyone has smartphones in Pakistan now, intuitive little things that can wake you up multiple times a night should you wish, this doesn’t diminish a tradition that has survived hundreds of years, be it in Talagang or Istanbul or Coney Island.

In Pakistan, the tradition takes on its own distinctive meaning. During dinner, Boota acknowledges the stigma that continues to attach itself to the Punjabi term, mirasee, colloquially used to describe singers, dancers, and musicians like him. The term stems from the Arabic word, miras, which can be translated as “heritage.” Historically, the mirasees in North Indian villages were the genealogists, the keepers of the family tree, the bards. Today, while mirasees still form an integral part of festivities in the country, the term has mutated into denigrating slang that connotes a lack of class. The Ramadan drummer serves to remind people of the connection between the sacred act of fasting and the country’s miras.

After dinner, Boota steps out of the house to see me off. A hush falls over the platoon of children in the front yard at the sight of their grandfather, a thriving Coney Island incarnation of the Pakistani patriarch. He is wearing his brightest costume, the neon green, which, one shade darker and several shades calmer, could be the color of the Pakistani flag. “When people see me,” he tells me as I leave, “they see Pakistan through me. I try to make sure they only see good things.”