Photographer Valérie Couteron has spent 15 years taking intimate portraits of men and women who do jobs seen as “undesirable”.

In November of last year, a pregnant young woman working as a supermarket cashier in northern France was suffering from extreme pain in her stomach. She asked for a break but was ignored by her supervisors. As the pain grew worse, even her customers were worried. When she told these customers to checkout at a different register, she was told by management to stay seated, as this wasn’t her break time. In tears, she noticed blood on her chair. She had had a miscarriage.

The incident created a national wave of indignation. On his Facebook page, presidential candidate Manuel Valls called the incident “revolting,” and saw in it a sign of a “dehumanized” society. He called for a political agenda that would reintegrate respect in the workplace. Other candidates followed suit, and then moved on.

Photographer Valérie Couteron spent two years in a similar supermarket, getting to know the women who work there and their working conditions. As part of her 15-year-long investigation into how work impacts people’s lives, she photographed them and many other women and men with jobs seen as undesirable. She spoke to R&K from Paris.

Roads & Kingdoms: Your series about cashiers is part of a larger body of work called “Corps Oubliés” (Forgotten Bodies). Could you tell us more about it?

Valérie Couteron: I have been looking at the role of work in people’s lives since 1998. At that time, I started with black and white, documentary-style photography in French factories. I was documenting the life of the working class. I photographed 10 to 15 factories, and would take photos of men and women at their work stations, and of their work environment. Little by little, my practice evolved and I got into color photography and I started concentrating on portraits. After that, my third phase turned to other places of work, like this supermarket in La Défense, near Paris, where I went for nearly two years.

R&K: How did this work come about?

Couteron: I had been photographing workers in a slaughterhouse before that, and the idea to photograph cashiers came from an assignment from a newspaper. They asked me to take the portrait of a cashier. I stayed half a day and I thought it totally fit my body of work. I wanted to get to know these women more, spend time there and tell their stories.

R&K: So you continued taking pictures in that same supermarket?

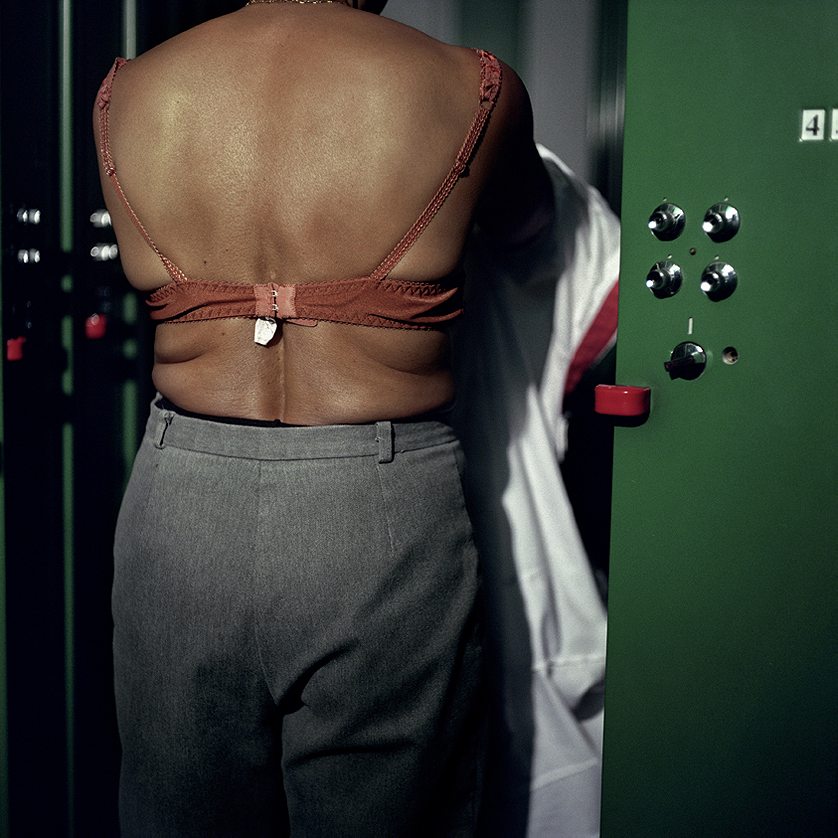

Couteron: Yes. After I photographed this one woman, I went through the process of getting authorization, which is always a bit complicated. This time, though, I was lucky. The supervisor was very nice and it actually went pretty fast. I got permission in just a few weeks. I would meet the women in the changing room there, which was in the basement without any sunlight and overall pretty depressing. I started out with portraits and made about 40 to 45. Some women refused, some were more difficult to meet up with than others, but in the end I was able build a strong series. I really wanted it to be an exchange between the person being photographed and me. The idea of photographing their backs came later. It wasn’t something I wanted to do at first, but the idea came little by little, by spending time with them in the changing room. I thought it was really interesting to see them leave this work uniform behind, a uniform that reduces them to workers, cashiers, who are behind a machine, typing all day, carrying heavy things, and being dehumanized. Taking off these uniforms, and seeing their skin, [seeing] their femininity reappear, I really thought it was quite beautiful. I wanted to photograph them as women, not just as cashiers.

R&K: How did they react to your requests?

Couteron: They were surprised because it’s rare for people to pay attention to them. But when I showed them my previous work, they easily understood what I wanted to do. They were mostly excited about it, about someone looking at them differently than just cashiers. Most of them time, they didn’t want to be shot in their work clothes. They asked me for a photo after work, outside, in their normal clothes. They would put makeup on and I would take that photo for them. Very few of them wanted to bring home a photo of them wearing their work uniform. Very few of them found this job fulfilling. They were mostly not doing it by choice, though some did say they were happy to do it because they saw a way of climbing the ladder.

R&K: It’s interesting to note that you take photos at the workplace, but never of the people actually doing their job.

Couteron: Yes. I started by photographing men and women behind their machines. But then I decided to extract them from that, just during the time of a photo, and I would either photograph them after work, or during their break. I find it interesting because the workplace is very present, even though it’s not seen.

R&K: People you photographed who worked on an assembly line could only leave their station for two, three minutes. How did you get the shot you wanted?

Couteron: Yes, that was in a sardine cannery in western France. I wasn’t really welcome there; management didn’t want me to stay very long. Each person would need to be substituted while they were photographed. They would splash a bit of water on their bloody aprons and they would follow me to a corner where we could have a real exchange. Even if it was quick, it could be very intense. For the cashiers, though, I did have much more time to meet them and really speak to them before taking their pictures.

R&K: Why are you interested in photographing issues relating to work?

Couteron: I think my interest comes from my background. My grandfather worked in a factory and I started this body of work by taking photos in the same factory he had worked in many years before. Work is something I wanted to investigate because we spend a huge part of our lives doing it. And specifically, I wanted to look at the people whose jobs make them invisible, people who aren’t represented, people who we don’t talk about. I find them brave. I wanted to pay attention to them. I’m not really trying to denounce anything. I want to tell their stories and go beyond their professional activity to show them as men and women, as humans who are often sidelined by society. The role of work in a person’s life is obviously not a new topic. From the beginning of the century, photographers have looked at the lives of men and women, and work has therefore become an inevitable topic. In fact, when I started photographing, I had in mind the images of August Sander, the German photographer who documented society under the Weimar Republic. His project, portraits of men in the 20th century, was to present different occupations, and not to look at the man behind those occupations. I wanted to document the working class. I veered towards people who for the most part had no qualifications, and who have difficult and low paying jobs. I find that photography can raise awareness, raise questions on the role this type of work occupies in society.

R&K: Speaking of which, let’s move on to the hotel housekeeper series.

Couteron: I met someone who knew someone who could connect me with two hotels in Paris. The series was all done at Hotel Costes, which is a luxury hotel. There, I spent time with these women, whom I photographed in the rooms before they started cleaning them. The idea came pretty quickly when I saw them working. I don’t usually work with diptychs but I thought it was interesting to see the rooms before they’re made perfect again. It said a lot about their work and though we don’t see them working, I thought it was stronger to imagine looking at the room they were in charge of cleaning.

R&K: Especially considering how dramatic these rooms are.

Couteron: Yes, the decorator wasn’t very happy about this series by the way. But yes, this décor is very specific, very dark, with deep reds and velvet, and they’re dressed in black. It’s a particular kind of atmosphere. The two images resonate well together, especially questioning the passing of time. Time is counted and closely monitored; they have between 25 and 30 minutes for occupied rooms and 45 minutes for check-in rooms.

R&K: A lot of your photos depict women. Is that a conscious decision?

Couteron: Yes, it’s true there are a lot of women. The cashiers were women, the housekeepers were women, in the slaughterhouse there were men, too. In my current project I’m also photographing women. Am I a feminist? It’s in my work, I express myself through my work. These women move me because they often have a double role: in addition to these difficult jobs, they take care of the kids, they work at home. Most of the time they are the ones running the household. There are quite a few women I photographed that were separated [from their spouse]. Often the husbands weren’t very present financially or physically, so they were alone and I found them beautiful and brave. Maybe it’s an homage to them in some way. But also, it’s what I want to photograph, it comes from my heart, and my head, and my stomach.

R&K: What would you say these women have in common?

Couteron: They’re all very different, actually, because what I’m trying to show is that each one of them has her story, her personality, her background. What they have in common, though, is hard work, routine, jobs that they didn’t necessarily choose. So, maybe courage. Some have told me they were taking these jobs temporarily, that they wouldn’t stay, but often they do end up staying for 10, 15 years. And do they ask themselves where the time went? A lot of them don’t have the luxury. They are in the urgency of today. It does raise this question of meaning, the meaning of work, of life. Why do I do this? How should I do this? Do I do it well? Am I heard? Not really.

R&K: For 15 years you photographed this theme. Where did it take you?

Couteron: It really depended on the access I could get, but I traveled throughout the country: a glass factory in Chalon-sur-Saône, where I did documentary and portrait work, in Brittany for the slaughterhouse. I sometimes used assignments from editors to meet people and ask to photograph their workplaces. I was often turned down when asking to shoot places. People were scared, I don’t know why, I guess to show what really happens in these places, or to show that their employees might not be very happy. I had many refusals in the food industry especially. But there are positive stories, too. Not long ago I was contacted by a cigar factory I had photographed in 2000 and that had closed. It’s becoming an art space next year. They had no archives of the factory; I was the only one who had documented what they did there, so I was happy to contribute to the memory of that place.

R&K: That brings up an important point, which is that many of these jobs are disappearing and French factories are closing.

Couteron: Yes. These are jobs that might disappear completely. I went three times to an Armor-Lux factory in Brittany. On my first visit there were between 100 and 120 workers in manufacturing. Ten years later, there were only 35 left. It’s a workshop that will be closed in a few years. All the manufacturing will be done in Turkey, or somewhere else where labor is cheaper.

R&K: France is nearing the end of a presidential campaign. How do you feel when you hear politicians making all these promises about factories not shutting down and protecting workers?

Couteron: It’s pathetic. It’s true that people use them for votes. All of a sudden everyone is visiting factories and speaking to the working class, but no one really cares. I think it’s fake, and it’s a shame. I find this sad. And sometimes people will fall for it, and will think that one candidate listens to them more than others. They are just demagogues. And when they start with this kind of speech, I don’t listen.

This interview has been translated from French by the author.