Inside the oldest and largest source of American-grown heart of palm.

The machete makes a zipping noise, followed by a loud crack. I try to guess what other U.S. industries are powered by guys with machetes. Probably not many.

Wailea Agricultural Group’s operation on the Big Island of Hawaii looks like a very small, lush lumberyard. Smooth logs are piled on the flatbeds of three John Deere Gators backed into a semi-circle against the packing shed. Beyond the gray metal walls, a sea of short, dark-green palm fronds flap under a clear morning sky, awaiting their fate by machete blow. My friend, who’s brought me to the farm in his Prius, arches a cynical eyebrow.

“You know, this is Hawaii’s new sustainable cash crop. Or, some people think so.”

A lot of Hawaiian farmers wonder what’s next after the final demise of pineapple and sugarcane. Del Monte harvested the last pineapple crop in 2008, Maui Land and Pineapple shut down in 2009, and Dole has moved all but a few acres in Oahu to Costa Rica, Thailand, and the Philippines. Just last December, Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company (HS&C) harvested their final crop and put the 36,000-acre parcel up for auction, closing the door on an industry that once brought over 300,000 immigrant laborers to the islands. Today’s profits are most easily reaped selling agricultural land to resorts and housing developments, but some small farmers don’t want to stop growing food; they just need to figure out which crops will let them earn a living.

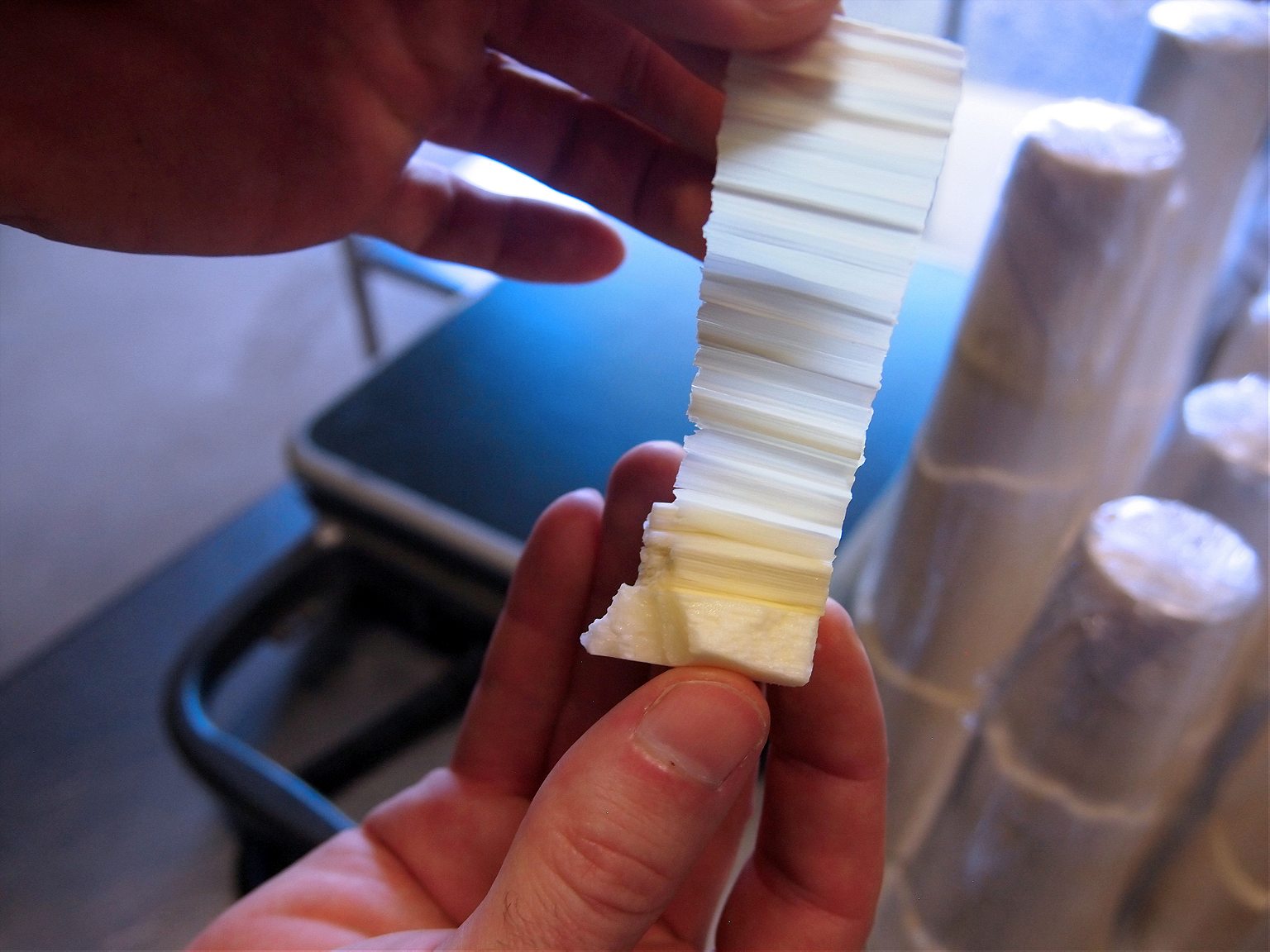

I watch as one man expertly zips the machete through the palm trunk, twisting to snap off the log’s outer sheath, which falls like parchment paper at his steel-toed shoe. He kicks the curl into a growing stack and picks a few sinewy strands off what’s left: the snowy white tube of the tree’s heart. He gingerly places this interior section aside on a stainless steel table before reaching for another log.

The palm heart, sawn into pieces and wrapped in clear plastic wrap, will be overnighted to high-end restaurants around Hawaii and mainland America, including to big name chefs like Alan Wong and Colin Hazama in Honolulu and Anita Lo in New York City.

Heart of palm is a vegetable delicacy in many ethnic cuisines. In Thailand, coconut hearts (yod-ma-prao-oon) are dressed in lime juice and peanuts or stewed in curries. In Brazil, the heart of Acai palm, better known for the purple superfood paste made from its fruit, is often tossed into fresh salads with avocado and lime. Native North Americans sometimes ate the heart of Florida’s state tree, the sabal palmetto, and canned heart of palm is eaten throughout the continental U.S., although the fresh version is largely unheard of. Even the heart of the date palm, with its yummy profusion of saccharine fruits, is sometimes consumed in northern Africa and the Middle East.

Mike Crowell, co-owner of Wailea Ag, waves us into the dimness of the packing shed. He’s got a grizzled gray beard and wears a baseball cap and sunglasses clipped to his collar. The metal walls cast blue shadows on his white t-shirt and the columns of palm hearts in shiny plastic wrap waiting to be packed.

Crowell and his partner, Lesley Hill, founded Wailea Ag in the early 1990s as a diversified farm specializing in exotic tropical fruits, flowers, and spices, a chef’s playground of flavors. He leans over a map of the 110-acre farm, color-coded according to crop, his brown finger flicking over gingers, heliconias, durians, citrus, and the palms. My cynical friend and I are actually visiting to see his rare fruit collection, but heart of palm is the farm’s economic core. Crowell’s 35 acres are the oldest and largest source of American-grown heart of palm.

Palm hearts started trickling into U.S. awareness as the expensive main ingredient for “Millionaire’s Salad.” The fresh dish was popular in the 1960s at restaurants frequented by the rich and famous, or at dinner parties where the host wanted to show off. Canned or jarred heart of palm became more widely available on supermarket shelves in the 1970s, when Costa Rica put in the first commercial-scale plantings, but fresh heart of palm is still a special order item; maybe not for millionaires, but for high-end chefs and sophisticated foodies.

Before we head into the orchard, Crowell grabs a six-inch-long stick for me to crunch. It’s mild, slightly sweet and yeasty, with a crisp, dense texture that’s somehow reminiscent of both jicama and mozzarella. The outer ring is firm, but the center is flakey. Crowell pinches it and pulls upward, unraveling the core into a thin, translucent paper accordion. Given time to grow, this would have become new palm fronds.

I glance through the open shed toward the field. A lone palm has escaped the machetes and towers a dozen feet over the rest. Mike follows my gaze and shrugs. “I guess we’re saving that one for later.”

The biggest challenge with growing Peach Palm is teaching people how to eat it

He describes his palm field like a savings account or rainy day fund. Unlike his other tropical crops, which are seasonal, heart of palm can be harvested at any time. If another crop fails because of rain or wind, he can harvest more palm. If demand is low, he can let the trees grow to harvest later. If he waits long enough, the trees also produce fatty orange fruits with a delicious nutty flavor. These fruits are what inspired German botanist Alexander von Humboldt to christen the tree the peach palm.

Known as pejibaye, pirijao, Peach Palm was a staple crop of the ancient Central Americans. They cooked its fruit like potatoes or brewed them into a fruity beer called chicha, and regularly ate its heart in fresh salads. They could harvest the heart frequently because, unlike coconut or date palms, peach palms grow in clumps of three to four trunks. Macheteing one stem not only doesn’t harm the tree, it encourages the growth of more suckers that can be harvested in just nine months. The trees are so resilient that Hill and Crowell don’t even use pesticides.

The biggest challenge with growing Peach Palm is teaching people how to eat it.

“There’s a lot of education involved because it’s a new crop,” Hill explains.

The result of the hours spent in hotel kitchens and with gourmet chefs is that heart of palm is now the darling of farm-to-table events around Hawaii and abroad. Colin Hazama, the Executive Chef at Royal Hawaiian in Waikiki, has been particularly innovative, blending heart of palm into chowder-like vichyssoise or pickling it and serving it with herb-infused butter and crackers.

The alternative veggie is even starting to appear at more low-key locales, like Tina’s Garden Thai Cuisine in Hilo. It’s my friends’ favorite restaurant, so we go in a big group and sit at several tables shoved together in a long, shot-gun room lined with ceramic fat ladies in Hawaiian-print swimming suits doing yoga.

We order almost the entire menu, including about five dishes featuring peach palm. We start with the heart of palm salad: blanched, crinkle-cut wedges over cucumber laced with lime juice, peanuts, fresh passion fruit, and mint, before demolishing a plate of the palm heart nut rolls, rice-paper spring rolls stuffed with heart of palm, creamy peach palm fruits, and sweet chili sauce.

Last, we order two Thai curries, medleys of fresh Hawaiian vegetables drowning in fatty coconut milk and spices. The heart of palm has the texture of potato and tastes slightly sweet, like an artichoke heart.

“Actually, the coconut heart of palm is sweeter,” Padina “Tina” Wu tells me later, over the phone. “But is more difficult to find, because when you get the heart of coconut you have to cut down one tree, so that’s why mostly we use peach palm.”

Wu opened her restaurant focusing on healthy, Thai-inspired cuisine in 2005. She hadn’t been open long when a close friend of Crowell and Hill’s, John Mood, came to pitch the excess palm stems he couldn’t sell to the mainland.

“Is there anything creative you can do?’” Tina says that Mood asked her. Open to the challenge, she did a little research. Over the phone she reads me the nutrition stats: in 100 grams, heart of palm has only 28 calories, no cholesterol, and lots of potassium.

“They’re really good for your body, so right there I just decided ‘How to make it yummy?’ Because lots of people like to eat healthy food but lots of people complain that healthy food doesn’t taste good.”

It’s better than a hamburger

In addition to curries and salad, Wu serves heart of palm in Thai-style burritos and pizza, soup with lemon grass, and even smoothies with coconut milk and honey. But her favorite recipe is really simple: grilled heart of palm.

“Sooooo good,” Wu enthuses. “You don’t need meat. With butter or just little bit of water, they’re good themselves. You can smell sweetness when you’re grilling them.”

Hill agrees that grilling is best. “If you take the stem and you put it on the grill, cut it into rounds and get grill marks on it, it’s better than a hamburger. It becomes very tender; it’s tender already, but it brings out the carbohydrates so it gets even sweeter.”

Barbecued is how she first fell in love with eating palm hearts. In the early 1990s, a Brazilian Ph.D. candidate, Charles R. Clement, came to study at the University of Hilo. He’d planted an experimental peach palm plot on the property of their friend, John Mood. On the weekends, Mood and Clement would sit with Crowell and Hill, drinking beer and waiting while the caramel aroma emerged from the barbecuing palm heart.

“And Charles would say, “When are you guys gonna start growing this?’ We said ‘It’s a little weird cutting hearts out of palm trees,’” Hill laughs at the memory. “But then he showed us the numbers.”

“What numbers?” I ask. “Oh, what we could possibly make off a crop, how many trees per acre, how many pounds you can harvest. We thought ‘Wow, it’s gotta be fun to make money at farming. Before then, we’d done tropical fruits and tropical flowers and nursery; it’s pretty hard to make a buck off of those.”

It’s the agricultural enigma of Hawaii: even with luxurious tropical produce, farmers struggle. The current market price of heart of palm, $9 per pound wholesale, is a tempting prospect.

But no crop will ever reach the scale or economic sway that pineapple or sugar once held over the islands. Even fresh heart of palm’s small, high-end market is threatened by competitors in the growing industries in Ecuador and Costa Rica.

Is heart of palm really Hawaii’s new sustainable cash crop? Can it save Hawaii’s farmers? Hesitantly, I dial +55. I’ve never called the middle of the Amazonian Rainforest before. Charles R. Clement picks up the phone. He’s now a researcher at the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas de Amazonia, in Manaus, Brazil. He’s blunt about his role in developing Hawaii’s peach palm industry.

“I had to apply to the U.S.D.A. to get some money, and the U.S.D.A. said we’re only going to help you get money if you create a market,” he explains. He says that by the late 1980s, when he arrived, U.S.D.A. researchers were already looking for new crops to give Hawaii’s out-of-work pineapple and sugar growers. Clement quickly realized that the key to peach palm’s Hawaii success is the state’s ethnic diversity and plethora of cuisines already familiar with using palm hearts. “Through the various different chefs, and ethnic groups, and all the culinary groups have you, all kinds of different uses were essentially invented.”

I ask Clement whether fresh Hawaiian heart of palm will someday be available on supermarket shelves on the mainland. He doesn’t think any Hawaiian crop will ever become available outside of Hawaii again.

Instead, he foresees people planting small plots of special gourmet products for the local markets. “There’s pineapple so sweet you’d think that you’d actually broken into a beehive, just wonderful sweet,” he says. There’s also things like coffee, and chocolate, and the citrus, herbs, and spices that Crowell and Hill grow in addition to peach palm.

The cash that can be earned from such crops is modest, but it’s what the few farmers left want to do anyway: grow good food for Hawaii.