The half-century of war and colonialism behind a favorite snack

DAKAR, Senegal—

Few people remember how spring rolls got to Senegal. Called nems in French, the fried snack’s golden-brown exterior is filled with glass noodles and ground meat or shrimp. They are Dakar’s go-to street food and beach snack, featured on most menus and served at every special event.

The story of Senegalese spring rolls goes back to 1947, when 14-year-old Jean Gomis boarded the SS Pasteur in the port of Saigon. He thought the ocean liner was paradise and grinned as he recalled the month-long journey from Vietnam to Senegal. Many of the families on the ship were like his. His Senegalese father, Emile Gomis, was a soldier in the French army, recruited from one French colony to serve in another.

His mother, Nguyen Thi Sau, was born in what is now Vietnam, and had defied society’s judgment by marrying a black man. While her husband was returning home after a long tour of duty, she was about to see the country where she would spend the rest of her life.

France sent more than 50,000 soldiers from African colonies to Southeast Asia in the decades leading up to its final defeat by Vietnamese liberation forces in 1954. Senegal was particularly well represented among the ranks. While the colonial infantry corps was drawn from many countries in West Africa, they became known collectively as the tirailleurs sénégalais, the Senegalese riflemen.

As many as 100 Vietnamese women moved to Dakar during the Indochina War as soldiers’ wives, according to Helene Ndoye Lame, the unofficial historian of this community. Lame can name 49 of them. Before weddings, she tells me, the Vietnamese women she knew would gather in one house and cook for two or three days, marinating pork, rolling spring rolls, and reciting poetry.

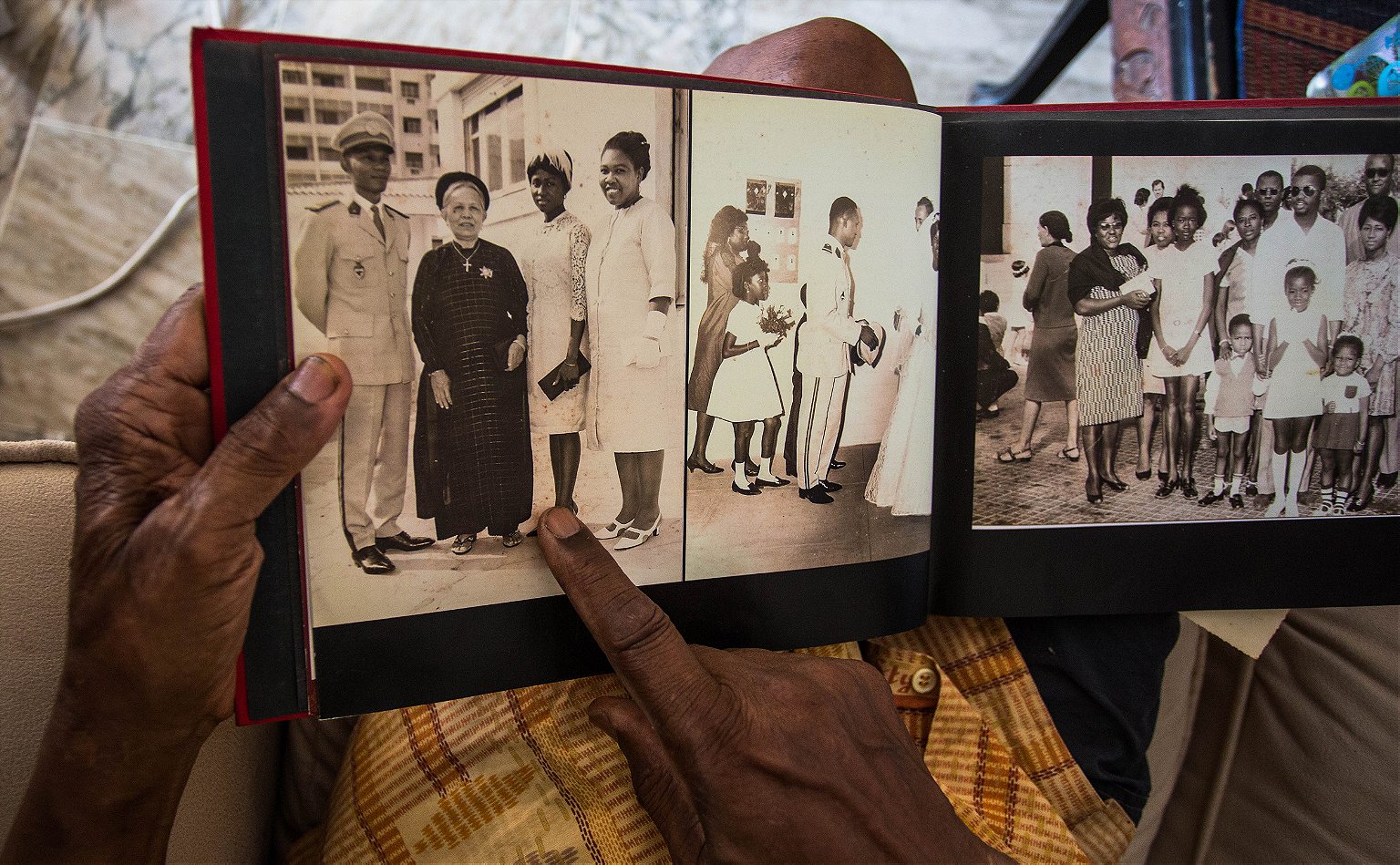

French culture was so dominant in both colonies at the time that many of the wives found that Senegal reminded them of home. Both places had French schools, bakeries, and architecture. “The ambiance was like in Vietnam,” says Jean Gomis, now 83. “I was in my milieu.” A retired army general, he is quick to laugh. In early photos, he stands tall and proud, handsome in his soldier’s uniform, next to his mother.

Merry Bey, a Senegalese writer and TV presenter, remembers her Vietnamese grandmother’s long silky hair. “I told my friends I had the most beautiful grandmother,” she says. Her grandmother wore only traditional Vietnamese clothing, which she made herself. On Sundays she and her friends would get together to cook and dance and sing songs from Vietnam.

But these families faced challenges too. Bey’s grandmother was rejected by the family until she learned the local language and converted to Islam. She never spoke about her past. “I saw that she suffered,” Bey says.

The women’s struggle in many cases was compounded by poverty. Their families were large, and a soldier’s wages under French rule were not. The women had to use what skills they had to make a living, and many did what they knew best. They set up stands in the pungent, crowded downtown food market, the marché Kermel, and they cooked.

Gomis’ mother taught him how to make a proper nem—moistening the rice paper just enough, and rolling it tight like a cigar before it dries up, then heating the oil—not too hot, not too cold—and making sure the rolls don’t touch. “In Vietnamese families, all the kids help cook,” he says. “It’s a great education.”

Though he joined the army before he turned 20, cooking has been a lifelong passion. On his rooftop in Dakar, he proudly showed me his potted collection of herbs. As he cooked for friends and family throughout the years, one young onlooker watched particularly closely. He would grow up to become Senegal’s best-known chef, Pierre Thiam.

“Uncle Jean was the only man I ever saw cook,” says Thiam, speaking over the phone from his home in New York, where he has lived since the 1980s making a career as an ambassador of Senegalese cuisine. His two cookbooks, Yolele! Recipes From the Heart of Senegal and Senegal: Modern Senegalese Recipes From the Source to the Bowl, enshrined the Vietnamese influence with recipes from Uncle Jean.

Thiam spent childhood summers with Gomis. “He was my great inspiration,” Thiam says. He loved the fresh salads his uncle used to make with mint and cilantro, the fried fish with lime, and his uncle’s pho.

Both cuisines make use of an intense umami flavor, Thiam says. Senegal’s national dish, thiéboudiènne, is a hearty mix of rice, fish, and vegetables stewed in tomato sauce and flavored with fermented fish and snails. When Thiam can’t find the fermented ingredients to make it in the U.S., he uses Vietnamese fish sauce instead.

Gomis is one of only three people left in Dakar who can speak, read, and write Vietnamese. Lame is another. Two hundred people used to come to the parties she would host for the Senegalese-Vietnamese families, but in recent years, she says, the community has gathered only for funerals. To her knowledge, only one of the original soldiers’ wives is still alive; she’s 92.

As the women who originally made nems have passed, methods have changed. “They’re not the same anymore,” Thiam says. “It’s night and day.” He often orders spring rolls when he returns to Dakar, hoping against odds that they will be as good as he remembers. But each time he is disappointed—today’s nems absorb too much oil, he says. They have lost their crisp.

Good Vietnamese food can still be found in the city, such as at Saveurs d’Asie, a takeout chain founded by the son of an immigrant. But it is the exception. Street nems, everyone told me, are woefully disappointing. So it was with great apprehension that I decided to try them.

Boubacar Diallo, 12, is my neighborhood spring roll seller. He mans one of the two-wheel carts that you see everywhere in the city. “How much for a nem?” I asked in French. He fished one out from a Tupperware container. It was still warm from being deep-fried on the grimy stove in his cart. He handed it over on a piece of newspaper spattered with grease, and I paid him 125 West African francs, about 20 cents.

The nem’s flaky, oily rice paper wrapper had the pockets of air that Thiam had warned me about—the sign of an unpracticed hand. But it tasted good. The meat inside looked edible, the noodles were glassy, and I even spotted bits of green, though I couldn’t identify the herb.

“I heard these are from Vietnam,” I ventured to Boubacar, gesturing at my half-eaten snack. He stared at me blankly. “What’s that?”