By staging the stories of child refugees, a photographer gives a new perspective to an old issue.

I first came across Patrick Willocq’s work a few years ago at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the south of France. His stunning project “I am Walé Respect Me” completely changed my mind about staged photography, which I had generally been adverse to until then. In the Ekonda tribe of the Democratic Republic of Congo, tradition dictates that women spend years in seclusion following the birth of their first child. Willocq asked young mothers to recreate the dreams they had during this time. The results—fanciful images of wooden trucks and women riding giants hogs—are breathtaking, and much more powerful than any documentary work on the subject could be.

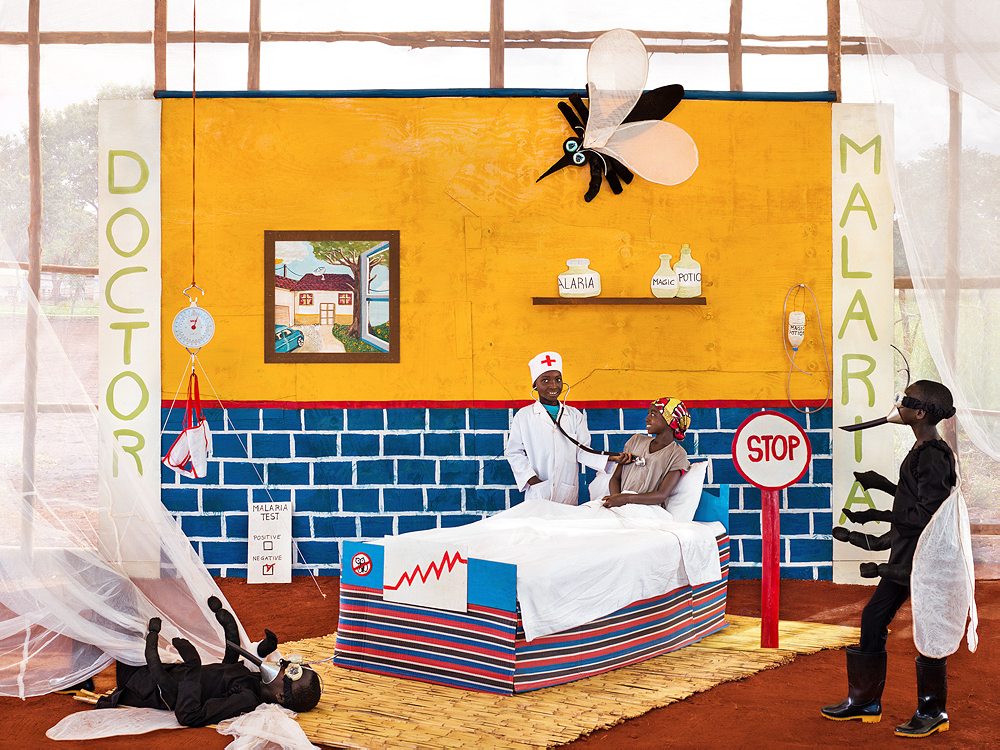

Earlier this year, Willocq created a new body of work in his now-signature style. “The Art of Survival” features child refugees from Syria and Burundi in scenes recreated from their lives. With this technique, Willocq provides an entirely new perspective on one of the most photographed topics of the year. He talked to R&K from Ghana.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did the “Art of Survival” project come together?

Patrick Willocq: Save the Children was looking to create something different by giving freedom to an artist to document what it’s like to be a child refugee. They approached a few photographers and requested pitches and I got selected. I really wanted kids to be involved in the process, and I think this is what they liked about my proposal.

R&K: Why were you interested in applying for this project?

Willocq: My work has always been about giving a voice to the people I work with, and so when I saw this, I thought I would be a good match for the needs of Save the Children. I thought that through participatory photography, I would be able to involve the kids in the process and have them interact with the stage and the sets. Having them act out their own stories is really what I wanted to do. Before applying, I googled “children refugees.” I knew what the result of the search would be, but I was still shocked to see it: it’s all the same stereotypical images of kids looking sad, dirty, with torn clothes. I really wanted to bring some humanity back to these kids, and give them the opportunity to be kids again.

R&K: Working with children can be very challenging. Did you have any experience before this project?

Willocq: No, but I get along with kids well, generally speaking. Some of these kids have gone through horrific stories and horrific experiences, but they are still kids and they still hope to be kids. Through the project, I really wanted to empower them physically.

R&K: Tell me about your process working with them.

Willocq: Save the Children organized workshops with me and the kids. We played games and I showed them my previous pictures and they got really excited about them, so we bonded that way. We chatted in group sessions, so some kids spoke more than others. But the kids that were more silent at the beginning slowly began speaking a little bit more. There was one little girl though who actually didn’t say anything at all. A tutor told me that she had lost both her parents and all her family members. Another child actually gave me a drawing, and that gave me an idea and I asked the kids to draw things for me. One of my images, the one of Walaa where you see the bombs that are flying, is a visual representation of two drawings she made for me. She actually just gave me a drawing one day, and I asked her: “draw me how your life was before.” She went back to drawing and she was really proud I was interested in her art. We had a dialogue that way and I decided to recreate the drawings in one photograph.

R&K: The sets you built are very intricate. Were you using materials found inside the camps?

Willocq: Paint and fabric we brought from outside the camp, but the rest, yes. I wanted to use the symbol of this place physically as a canvas for children to express themselves. That was the idea. But it was really a participatory process. In Lebanon we even worked with someone who made curtains. He had been a refugee for two or three years and he really was happy to do this craft from his previous life for us. The project gave a confidence boost to kids and to adults we were able to work with.

R&K: In a way, this project is much more than just a photo series, it’s about the experience of making it.

Willocq: Yes. The shooting process lasts around 45 minutes, let’s say, but it takes hours of working together, of building together, of exchanging, painting, drawing, etc. It’s a whole process. It was very hard to leave at the end, both for them and for us, because we had created something together. Sometimes I say that their life in a refugee camp is in black and white, and suddenly their life became color. And you could see it on their faces. One dad came to see me and said that us working with his child was making a huge difference. He said he was happy, like before back at home. It was very rewarding for everyone.

R&K: What were your relationships like with the parents of these kids? Were they involved in the project itself?

Willocq: Some of them were. One parent was our translator and coordinator on site. Another one in Lebanon, she was also a painter, another one was a tailor, so yes, they were involved based on their skills and what they could contribute to the project.

R&K: How did the experience change your opinions on refugees?

Willocq: I knew the stereotypes. I was confronted with them years ago with my Congo work. I always tried to show a different image of the country. I’m very skeptical about the stereotypes that are perpetuated by the media. Very, very skeptical, because I know they’re not true. I knew that I would find other things than what the media is showing, I knew that I would find real kids there. This project was my first big assignment with an NGO and so there’s a cause associated with it, it’s not just an artistic project. They’re using the images in their efforts with decisions makers, politicians, the U.N., so I see that this work is potentially useful and can potentially help people, and I feel a responsibility toward that. I don’t want to fail them.

R&K: What do you think the future of these children looks like?

Willocq: Most of them are still in the camps in which I met them. In Lebanon, Syria was just opposite the mountain behind us. Their country was right there, but I have no idea when they can expect the conflict to end. And then in Burundi, we just don’t know. There were resettlements to another camp because the one [we were in] was too crowded, so I hope it’s more comfortable with less people, and has easier access to some vital services.

R&K: It’s fascinating to see that you’re looking at the very same issues the rest of the media is looking at, and yet you’re able to achieve wildly different results.

Willocq: Yes, I think that’s the idea. That’s what I enjoy. I think it’s so fulfilling, rewarding, and it’s important to move away from stereotypes, because when you look at refugees, what’s happening through Europe, people don’t consider them as humans. But hey, this could happen to you, this could happen to me, this could happen to anyone. It’s total hypocrisy. That’s what I wanted to do, humanize the stories, show them as kids with hopes and dreams and fears and everything. There are so many other causes, so many other people that need to be shown differently, with a fresh visual interpretation of their situation. I’m really keen to carry on.