Drinking Vodka, Making Pisco

Drinking Vodka, Making Pisco

Screwdrivers in Chile

Pacán sells his pisco in repurposed vodka bottles. His tasting room consists of an old barrel upon which he sets as many or as few samples as he sees fit, in glasses that are best not carefully examined. His house is dilapidated, his property is a mess, and he is known in the area as el pisquero loco (“the crazy pisco maker.”)

He also happens to make some of the best pisco in the Elquí Valley.

I went to the valley specifically for the alcohol. I’ve had my fair share of Pisco Sours over the years, and I wanted to learn more about the grape brandy that both Chile and Peru claim as their national spirit. Unfortunately, my job in a local hostel was seriously getting in the way of my distillery visits. The hostel was beautiful and charming, as promised, but my agreed-upon schedule of half-day shifts had somehow stretched into a full-time job for which I did not get paid.

Frustrating, to say the least. So when the crotchety pisquero down the road invited me to come see his distillation process, my coworker Jenny and I conspired to get out of our usual hostel duties to visit our neighbor.

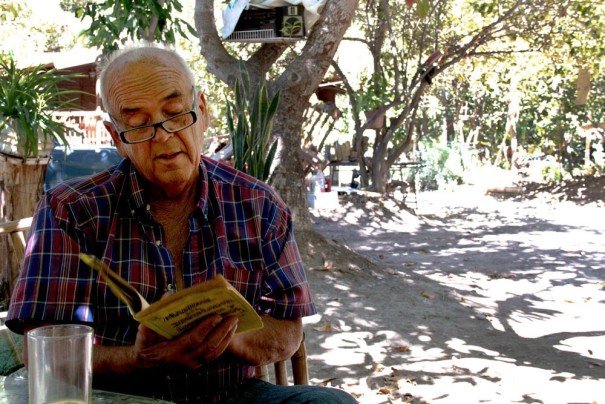

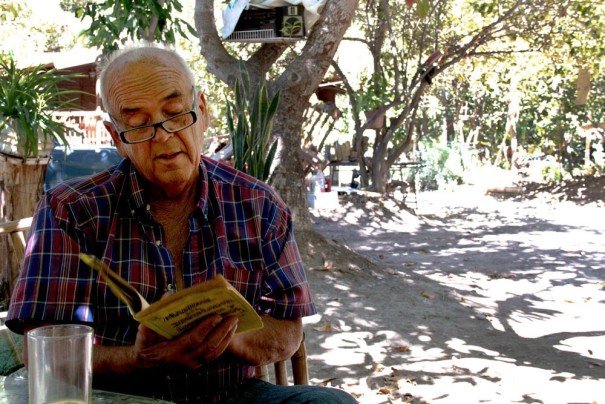

We arrived at Pacán’s place a little after noon. Our host was having a hard morning: his 94-year-old mother was in the hospital with a broken hip, and he was drowning his sorrows in some midday Screwdrivers. He poured glasses for Jenny and me, both decidedly light on the orange juice, and we drank vodka and chatted in Spanish until my head was spinning.

The portrait of Pacán’s life that I formed was built of small clues, casual asides. He’d had a wife once, a good job—there was even a mention of a son about my age. But now Pacán lived alone, selling a spirit he didn’t even drink himself to a thin trickle of tourists and imbibing unlikely quantities of vodka. I wanted to know more, but he was more interested in hearing about us: these wide-eyed young women with foreign accents and uncertain travel plans. “You’re very brave,” he said, over and over. “And very kind.”

After an hour or so we managed to convince Pacán to get started. The still, out of sight at the back of his property, was a mess of plastic drums, lumpy concrete, and blackened steel. It looked more likely to produce toxic waste than artisanal liquor. But I knew how good Pacán’s brandy was, and some minor aesthetic concerns were not enough to put me off.

Pacán began by setting his drink down and taking off his shirt, exposing his enormous and deeply tanned beer belly to the autumn sun. He opened the still’s boiling chamber and I shoveled out the pungent remains of the last batch’s mash, throwing them into the trash heap next to the still while Jenny hauled a fresh drum of fermenting grapes across the yard to take their place.

I resealed the chamber, tightening the nuts while Jenny filled the cooling chamber with water from a nearby stream and Pacán loaded a mixture of wood and garbage into the stove beneath. I cringed inwardly as I watched, but I was his guest and it was hardly my place to protest as the plastic coat hangers and grocery bags twisted in the flames.

The first liquid to come out of the still was cloudy and bright. The heads, as those first couple ounces are called, are seriously toxic, and Pacán poured them out into the dirt, then placed an empty wine bottle under the spout to collect the good stuff.

“And now?” Jenny asked.

“And now we wait,” Pacán said, and poured us more vodka.

By evening, Jenny and I had resorted to pouring our Screwdrivers out into the stream while Pacán wasn’t looking. It was bad enough that we’d left the hostel for the whole afternoon; we didn’t want to go back drunk, too. But his aggressive hospitality and bare stomach aside, Pacán had charmed us.

“Come back soon,” he told us when we finally left. And we did, stopping on our way out of the valley for a quick visit less than a week later. I hope it’s not the last.