A photographer’s odyssey to cover an escalating conflict.

As the large wooden boat pulled alongside the docks of Makha, a port city in Yemen, two four-wheel-drive pickups appeared, mounted with large Russian guns called duskhas pointed straight at us. This wasn’t quite the welcome I was hoping for. I thought—even the United Nations thought—that the Houthi rebels were not in Makha. I cursed under my breath—well, here goes—as I gathered my camera gear and prepared to disembark.

Welcome to Yemen.

In January, Yemen’s government fell to the Houthis, a predominately Shia Muslim group thought to be backed by Iran, though the group denies that it is taking orders from Tehran. This was viewed as a threat to Saudi Arabia and the neighboring Sunni states, which formed a coalition and began bombing campaigns in the capital, Sana’a, and Aden, a port city, where a resistance force was battling the Houthis. Shortly thereafter I started looked into ways to get into Yemen: I wanted to be among the first wave of reporters to cover the war.

My colleague Lindsey Snell, who works for Vocativ, was working on the visas. She was in touch with a fixer on the ground who was asking for extortive amounts of money to arrange our passage into the country. I was in Istanbul, using my connections with humanitarian groups and the U.N. to gain access in Yemen. Together we had been struggling for more than a week to make this happen.

The emails went back and forth. The only solution was to travel to Djibouti, from which humanitarian aid organizations were sending boats to Yemen. Unfortunately I couldn’t get reliable information on when the boats departed until I read about them in press releases long after. We talked about renting a boat, but that would be costly and tough to justify on my freelance wages. Conflicts these days are increasingly covered by freelance journalists and photographers like me, as big media outlets balk at the cost and danger of sending their own people.

Eventually we heard that the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) would be running flights from Djibouti to Sana’a. We boarded the red eye flight from Istanbul to Djibouti, packing our bags lightly. Djibouti is a small African country, once colonized by the French when foreign powers were staking out claims in the Horn of Africa. It is an expensive place to travel, largely because many foreign nations, including the United States, have military bases there. As I disembarked from my flight I could see drones parked in hangars on the edge of the tarmac.

BBC, Sky News, the L.A. Times, and the New York Times had already arrived. We waited in the airport for the flight to Sana’a, dozing on chairs. Over four hours passed and there was still no sign of our flight. Our morale dropped, and Candy Crush was no longer helping bide the time. Finally George, the WFP coordinator, announced that they could no longer take us.

I made inquiries to Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross to find an alternative solution. Finally, a Doctors Without Borders staff member broke it to me: Saudi Arabian officials were monitoring who was getting on flights or boats. If a journalist went along, the NGOs would be denied access to the country.

Saudi Arabia was cutting access to electricity, food, oil, gas, and medical supplies in Yemen. The strategy seemed to be to starve the population of some 26 million people until the people turned against the new Houthi government.

By now it was mid-May. We reported a few stories in Djibouti about the refugee crisis as we looked for other options to get into Yemen. Hundred of Yemenis who were American citizens trying to flee to the U.S. sat idly in a large warehouse on the docks, waiting for transport out of Djibouti. It was there that they told us they managed to jump on a large dhow boat from Yemen to Djibouti. The boat ride would be around 16 hours—a grueling 16 hours under the equatorial sun.

We started looking for a boat and soon found one that would be bringing cattle into Yemen. With my bad Arabic I asked if we could hitch a ride, and the boat captain agreed. Unfortunately Vocativ did not approve of the trip because of security risks. But while Lindsey faced the possibility of losing her job, I was just a freelancer stringing for them.

“Go,” Lindsey said. “Someone has to make it there.”

She gave me money to help pay for the trip, and I arranged the journey.

This is where things got complicated. I had promised an NGO that I would take media equipment and solar panels with me to Aden to help set up their center and teach media. The radio transmitter seemed a bit suspect to bring into a war zone, but I was confident I could pull it off. As I waited for the boat, I watched cows being hoisted up by crane into the dhow all through the night. Djibouti officials initially didn’t want me to board the boat and refused to stamp my passport on the way out, but they eventually relented.

Several Yemenis were taking the boat with me. Some had been staying in Obock, the refugee camp set up by Djiboutian authorities and U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. The camp lacked electricity, was scorching hot with searing dust clouds, and lacked facilities of all kinds. The Yemeni refugees told me they would rather go home and risk death in Yemen than stay at the camp.

As the crammed boat set sail, the Yemenis with me gave me qat to chew, saying it would make the long journey bearable. Qat is a highly addictive plant that grows in the Horn of Africa and that, when chewed, acts like an amphetamine stimulant. Men gather together in packs and chew for hours. Apparently it takes three hours to for it to kick in and you need a regular addiction to be able to reap the benefits. I chewed and chewed and developed a buzz not unlike drinking a pot of coffee. The Yemeni men waxed on about the myriad benefits of the drug: appetite suppression, weight loss, increased focus, and improved sex drive. We went on chewing.

After 16 hours we reached port and were greeted by the Houthis driving the two pickup trucks with duskhas. Slight fear hit me, but I was used to this. I’ve covered conflicts in Somalia, Sudan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Syria. I’d met rebels, warlords, smugglers, and thieves. I can handle this, I thought to myself. The Houthis went through all my bags; they were concerned about the solar panels and the radio transmitter. I could hear them mutter. I smiled and gave a stupid look. The best rule at times like this is to play dumb, be genuinely friendly, even if the aggressors are angry, shake their hand and greet them. No one wants a smart ass.

Some Houthis with AK-47s accused me of being a supporter of the ousted President

We went to the customs office. The Governor of Makha was on his way; the people were muttering about how a foreigner made it across the sea. My Arabic isn’t great, but I had contacts in Aden and Sana’a. They were adamant that the radio transmitter was for the resistance force in Aden and not for a radio station that locals needed to use.

I heard the click of chambering a bullet. Some Houthis with AK-47s accused me of being a supporter of the ousted President Abd Rabbuh Mansur al-Hadi, in exile in Saudi Arabia since January.

“Now why would I do that?” I said. “This is not my country. I came here to tell your story.”

The Houthis agreed to let me go, but not until I showed them papers that proved I had permission to be in Yemen. Our fixer in Sana’a had prepared papers for Lindsey and me, but had mistakenly written that I was Austrian and not Australian.

They inquired about Lindsey’s whereabouts, and asked why there was a spelling mistake. The letter was addressed to the Yemeni Consulate in Turkey. They wanted it addressed to them. We went back and forth, questions and answers. They asked for some kind of travel letter, and I had no idea where I was supposed to get this.

The guards sent me to the office of a port custom officer called Nasser. I was to stay in his office under house arrest until the mess was sorted. The Houthis took my cameras and laptops, but allowed me to keep my iPhone. Nasser was not a Houthi, he was a civilian who had somehow managed to still hold onto his job as the Houthis took over Makha. He was friendly and spoke decent English. He offered me qat. I was hungry and I decided to be friendly with Nasser. After all, he could be a good source of information and might help me out of my predicament. And most importantly he had the Wi-Fi password.

Once I got online, I contacted as many people as I thought might be able to sort all this out. It wasn’t going to be easy, mostly because I was in a warzone and the rules and requirements were changing by the minute. I did what I could and sat chewing qat with Nasser and friends. They put a Houthi minder on me in case I might try to escape. The minder chewed his qat and sat in the corner unbothered, even when I got up and headed outside to walk around the port. He knew that even if I wanted to flee it would be difficult to negotiate a boat or bus ride.

Nasser was replaced by a man named Abdul Rahim, who told me about the days before the civil war and the famous coffee in Makha. I would have killed for some coffee. There was no food in the port and I would have to wait for it to be brought to me. The Houthis later brought me a stale Iranian chocolate sponge cake and more qat. Dinner was replaced by qat. It began to hurt when I chewed and I wasn’t feeling anything. Eventually I lay down on a dirty mattress and fell fast asleep.

In the morning I was hopeful that my contacts had sorted out something for me. Nasser came back with some Makha coffee. The prices had tripled, but he wanted to make sure I tasted the coffee that makes the place famous. He handed it to me in in a glass jar.

I ate lunch (and chewed more qat) with the Houthis. I needed to convince them to let me go, even if it meant leaving the gear behind. The Houthis believed I was planning to take the equipment to a port in Aden controlled by the resistance force loyal the Hadi, the ousted president.

I got in touch with my fixer; he wanted a ludicrous amount of money to collect me from the port, and he wanted this money upfront. The last few times we’d given him money upfront, he did not return it. I had some money on me but I wasn’t interested in parting with it. I told him that he would have to pick me up first, and I would give him half when he arrived and half when I was delivered to Sana’a. The Houthi agreed that my fixer could come get me. I had another day, they said, otherwise I’d be on a boat back to Djibouti.

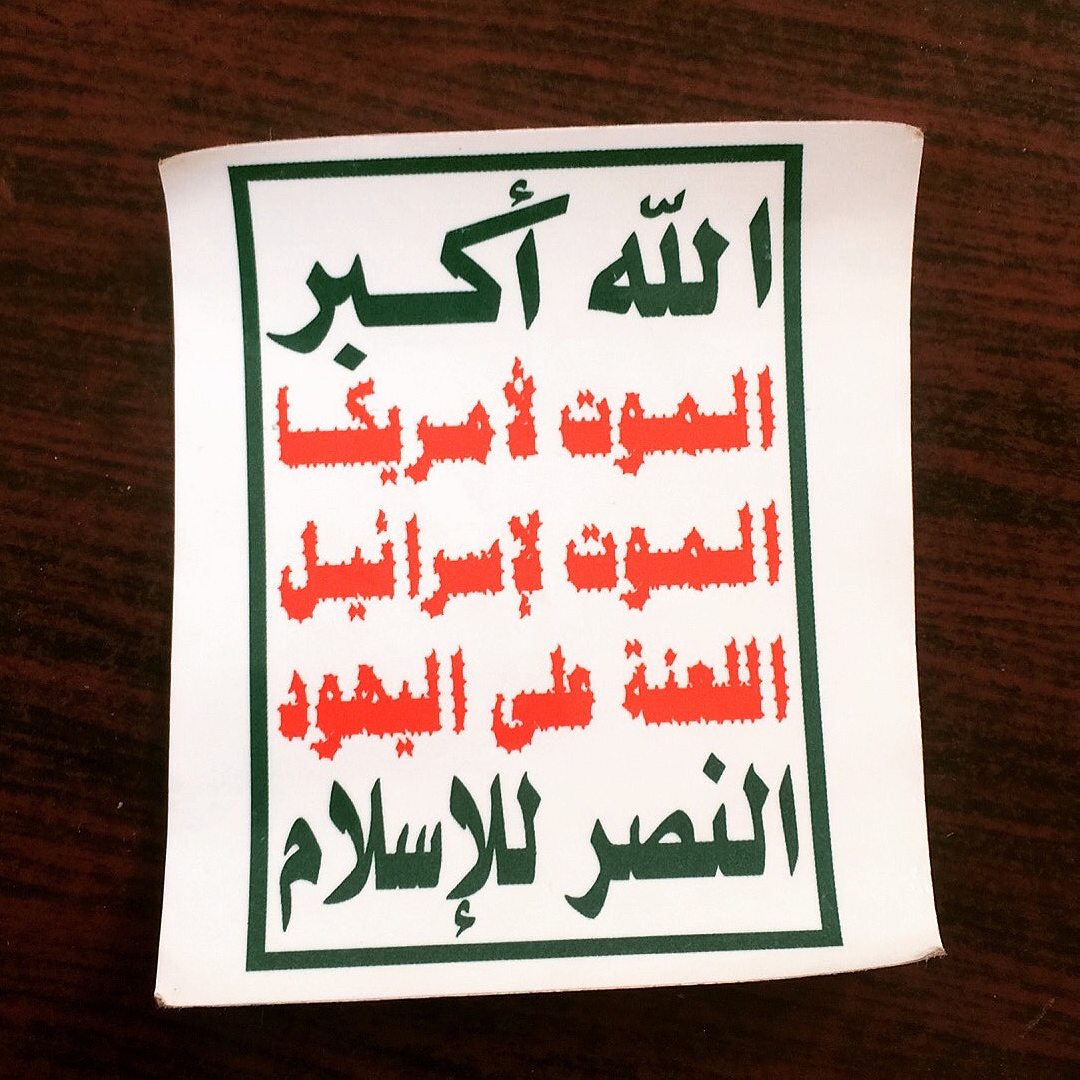

There was more qat. By then I had no interest in chewing qat, but it was a good chance to converse with a learn more about the Houthis. All of the fighters guarding the port were young, from 16 to 24, most were uneducated and unmarried. I answered their questions about life in the West with my rusty Arabic. Oddly, the Houthi who showed the most interest in America wore a shirt featuring the movement’s official motto, “God is great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse the Jews, Islam is number one.” He told me he would like to visit America. Maybe not while wearing that shirt. As a souvenir of my visit he gave me twenty stickers with the same slogan.

After the third day it appeared my fixer had abandoned me for not giving him the money up front. The Houthi commander shrugged and said that my fixer was “a bad man.” There was a short discussion among the men and soon enough I was on a boat back to Djibouti.

The governor paid for the trip. I would be on a ship with about two hundred refugees. I was given my cameras back and boarded the crowded boat. Most of the refugees were U.S. citizens, like Sharaff al-Mahdi, a young Yemeni-American who grew up in Cincinnati. All the refugees were welcoming, and they gave me bottles of water and soda for the long ride. Qat was offered, I accepted: It was going to be a long trip.

We talked about life in Yemen. It was hard times. There was little electricity, sometimes just an hour or two every three days, and gas and fuel was at a minimum. People waited in long lines. The Houthis were distrustful of the Sunnis and many had migrated out of fear of violence. ISIS and al-Qaida were blocking most of the roads between Sana’a and Aden. But most were fleeing because of the random Saudi bombing. Sharaff translated for me. He was a great kid, and his family had sent him to the U.S. in hopes of getting a job and to help bring the rest of them to the States. He hadn’t showered for weeks, but he was jovial; the refugees all used humor to lift their spirits.

After a rocky 17-hour boat ride I could finally see the shores of Djibouti. I was drenched in sweat, and glad to be back. I wished Sharaff all the best with the U.S., and hoped that he’d make it.

Cover image: Franco Pecchio