In the far reaches of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic, the decaying compounds of brutal dictators reflect an era of corruption and greed that haunts the region today.

In the remote north of the Democratic Republic of Congo, in the tiny village of Kawele, sits the decrepit, melancholy palace of a dead tyrant. It’s not exactly a tourist draw, and yet here I am, waiting at the foot of a 2-mile-long road for someone to open a large set of metal gates. Before long the village head arrives, dressed in shorts and t-shirt. After I pay a $15 dollar fee, he unlocks the gates and invites me to follow him up the winding driveway.

The village consists of simple mud and thatch houses that jar awkwardly with the great generosity their one-time neighbour bestowed upon himself. The man who once lived next door was Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, the notorious dictator who ruled Zaire (now the DRC) between 1965 and 1997. The town from which I have just made the 15-minute journey is Gbadolite, the former president’s ancestral village.

This is the first of two once-lavish compounds I’ve come to explore—the other across the border in the Central African Republic, once home to Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa, who ruled and terrorized the country from 1966 to 1979. Both palaces reflect an era of corruption, greed, and brutality that reverberates in the two war-torn countries today.

In Kawele, where Mobutu and his family once luxuriated, the palace is now a ruin. The roof is long gone and only an exoskeleton remains. The swimming pool is empty, filthy, and cracked. Everything is weeds and smashed masonry. I amble through the debris accompanied by villagers, their flip-flops clacking as they stroll. At one time, servants would have carried champagne buckets and platters of chilled salmon. The panorama from the hill on which the palace is perched is stunning and the vegetation is steadily reclaiming this emblem of corruption.

In 1960, the year the DRC secured independence from Belgium, Gbadolite was an unremarkable village of 1,700 souls. If not for Mobutu, chances are it would have remained that way. It is situated in the DRC’s far north and enveloped in dense rainforest. It was never an obvious choice to be the beneficiary of generous attention from nation builders. Yet, Gbadolite’s most famous son had other plans, and they were mesmerizingly grand. Mobutu constructed two lavish palaces—one for hosting affairs of state and a private residence at Kawele, seven miles outside the town—and a village of Chinese pagodas. These shrines were stuffed with Italian marble, antique French furniture, Venetian chandeliers, expensive tapestries, and monogrammed silver cutlery. Fashionable chefs, Parisian patisserie, and Belgian mussels were flown in from the capital cities of Europe.

Gbadolite’s airstrip was extended to accommodate a Concorde, which Mobutu would charter from Air France. The cellars burst with thousands of bottles of pink champagne and vintage wine. It took almost 1,000 expensively uniformed staff to keep the palaces shipshape; guests included Pope John Paul II, Boutros Boutros Ghali, several French presidents, and a ‘who’s who’ of questionable businessmen. One Congolese politician has estimated that Mobutu spent up to $400 million on his Gbadolite palaces.

Mobutu heaped further largesse upon the town he created. He built a luxury hotel (owned by the Mobutu family) to house visiting dignitaries and a hydroelectric plant to supply Gbadolite with constant electricity. He established a Coca-Cola bottling factory as banks and other businesses rushed to set up branches in the town. As Mobutu’s reign continued and the DRC’s economy crumbled, Gbadolite thrived.

The town declined along with the dictator. By the mid-1990s Mobutu was sick with cancer and had more or less abandoned Kinshasa, the nation’s capital, to unreliable subordinates, preferring to spend his time in comfort in Gbadolite surrounded by his family. On top of decades of mismanagement, Mobutu’s steady withdrawal from public life helped create a vacuum into which stepped Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the leader of the rebellion against Mobutu. Bolstered by the support of Rwanda and Uganda, Kabila swept through Congo from the east, forced the Mobutu family into a Moroccan exile, and seized control of the country in 1997. Mobutu’s exit deprived Gbadolite of its raison d’être and sent the town into a sharp decline.

Eighteen years later Gbadolite still shows few signs of recovery. The palaces have been looted. Jean-Pierre Bemba, a Mobutuist rebel leader-turned-prime minister, took over the town in 1999 in a move welcomed by most of Gbadolite’s residents, who were eager for peace and a return to normalcy.

Nowadays foreign visitors can only visit Kawele; the larger palace is now an official military base housing thousands of Congolese soldiers. I was turned away by an apologetic private and sent to his colonel to seek permission to enter. The officer refused me access. Nevertheless, there are photographs taken in the early aughts, which testify to the extent of the devastation wrought there.

Gbadolite, which seems to owe both everything and nothing to the former president, is fossilized in 1997. Building projects remain unfinished while cranes and other machinery rust. The Coca Cola factory has packed up and the state-of-the-art equipment sits idly. There are more carcasses of motor vehicles dotted around the town than working cars on the increasingly potholed roads. It strikes me as masochistic that Gbadolite’s inhabitants have not simply pulled down these physical reminders of a more thriving time.

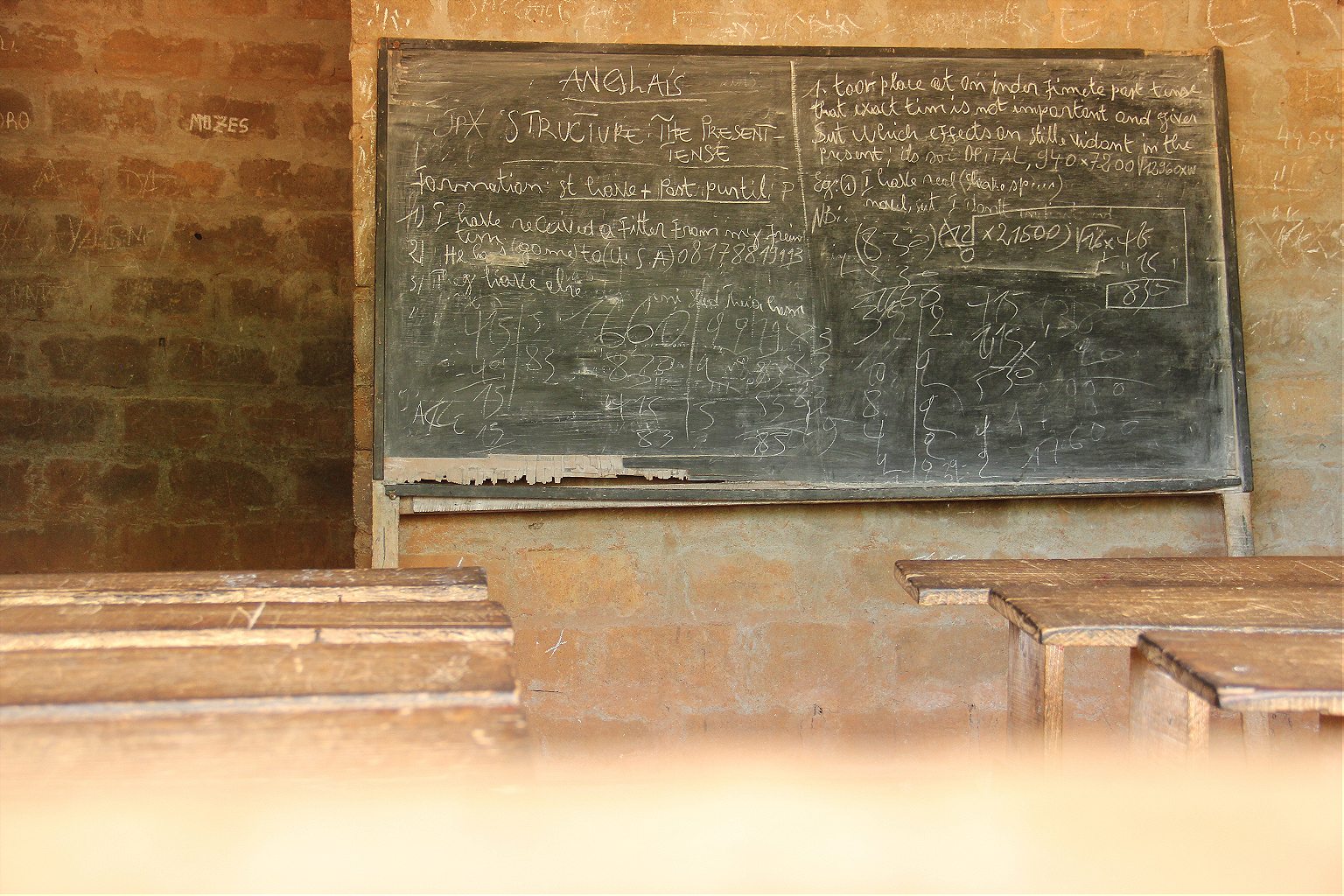

Wandering along Gbadolite’s main thoroughfare I see two stone hulks that were supposed to serve as the headquarters for the water ministry and a company belonging to the presidential family. Neither has been completed nor had a day’s work done on it since Mobutu sulked off to Morocco. They serve a function, however; the bottom floor of each edifice has been appropriated by schoolchildren. Wooden desks and blackboards are arranged in an orderly fashion in the lower rooms. Children in neatly pressed white shirts pack themselves tightly into these unfurnished caves.

Arguably the most depressing site in Gbadolite is Motel Nzekele, the hotel that opened in 1979 and once played host to world leaders and captains of industry. It is now in a state of disrepair. It is still owned by the Mobutu family, although staff members are not sure exactly which family member is the proprietor, or where they live—Europe? America? Morocco? Kinshasa? Nobody seems to know for sure. The shelves of the kitsch bar hold dust rather than bottles. The swimming pool is bare and grubby. The cinema can no longer project a film or seat viewers. Perhaps the gloomiest thing about Nzekele is the missing patrons.

One afternoon local doctors meet here for a seminar, but during three other visits I run into only the skeleton staff that maintains the hotel. One employee, Barthelemy, a restless and animated man, is nostalgic, like many citizens of Gbadolite. He mostly misses being busy, having something to do.

As we sit alone in the poorly lit bar, he leaps up, grabbing a now obsolete telephone in the corner, and waxes lyrical about the years he spent running around following the whims of presidents, heiresses, and businesspeople. He reminisces fondly about their demands for food and booze from every part of the world, at all hours. “We ran out of everything. It was terrible but magnificent. Magnificent! There were cars everywhere, money everywhere, and work everywhere.” He sighs. “Now, there is nothing. Life has changed.”

Considering Gbadolite’s decay, I find it strange that the Mobutu family is still revered and that the town’s anger is strictly reserved for those who replaced him. One of Mobutu’s numerous sons represents Gbadolite in the national parliament, having won several elections in landslides. Locals blame their ills on the politics of faraway Kinshasa and the Kabila family. (Laurent- Désiré was succeeded by his son Joseph in 2001).

The town’s residents feel that they have been punished by the country’s leaders for the town’s association with Mobutu and then Bemba (who currently languishes in The Hague, awaiting trial for crimes against humanity and war crimes). The people of Gbadolite discuss the president and the mayor he appointed to govern the town with a mixture of disinterest and contempt. “We have been abandoned,” is a common refrain.

One of Gbadolite’s few growth industries in recent years has been in aid work. The U.N.’s refugee agency has set up a major office in the town and been kept busy by the many thousands of Central Africans who have crossed into the DRC, escaping interreligious bloodletting in the Central African Republic (CAR). About a quarter of the nearly 100,000 Central Africans who have sought refuge in the Congo have been housed in a couple of tarpaulin cities near the town. The violence to Gbadolite’s north has put further pressures on an area that is reliant on the CAR for most of its imports because of the poor logistics networks in the Congolese interior.

Several hundred miles west of Gbadolite sits Bangui, the traumatised capital of the CAR. The city has been the setting for horrifying sectarian fighting since a mainly Muslim rebel alliance, the Seleka, tore through the country in late 2012 and deposed the president, Francois Bozize, in March 2013. Nine months later the anti-balaka, a coalition of militias, poured into Bangui in the early hours to drive out the Seleka and reclaim the CAR for the Christian majority. As the Seleka’s fighters either died or ran away, the anti-balaka’s objectives swiftly evolved from repelling the militants to cleansing the country of all its Muslims. They nearly succeeded and 18 months later Bangui is only beginning the process of tentatively piecing itself back together.

It has had a uniquely dreadful couple of years, but the CAR has long been a benighted expanse of land, described by one international NGO as “virtually a phantom state.” A good deal of responsibility for its misfortune can be laid at the feet of Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa, who took power in 1966 after ousting David Dacko in a military coup.

During the 1970s Bokassa upgraded his position first to President for Life and then Marshal of the Republic, but still he wasn’t satisfied. In 1977 he decided to stage what might well rank as Africa’s most megalomaniacal post-colonial event and was duly indulged by his patron, France, which provided $22 million for his coronation. After proclaiming himself the Emperor of Central Africa, he and his guests set to work on 24,000 bottles of Moët & Chandon and 4,000 bottles of Château Mouton-Rothschild and Château Lafite Rothschild.

Less than two years later Bokassa would personally participate in the torture and murder of protesting schoolchildren within the walls of Bangui’s notorious Ngaragba prison. This outrage proved a tipping point and finally exhausted France’s patience. In September 1979, while Bokassa was out of the country, French commandos swooped in to reinstall Dacko.

At Bokassa’s two most lavish residences—Villa Kolongo and Villa Berengo—French soldiers found pornographic videos, diamonds, mutilated corpses in freezers, and the bones of victims who had been thrown to pet crocodiles. In the mid-1980s Bokassa voluntarily returned home to face trial and was given a death sentence, which was later commuted. He was released after seven years and died unremarkably in 1996.

A week or so after leaving Gbadolite, I head out of Bangui in a battered yellow taxi on the 50-mile journey to Berengo, the village of Bokassa’s birth and the site of his imperial court. It is an arduous and unsettling day, due both to continuing tension in this recovering country and the suspicion the CAR authorities display toward foreigners who ask questions about their former emperor. Stopped at a roadblock on the way out of Bangui and interrogated by the police—“You are not Central African,” “Why do you want to visit Berengo?,” “Are you a journalist?”—I was returned to the central police station to request permission for my visit.

After the police headquarters sends me to the tourism ministry, several hours later—now holding a letter of authorization signed by the ministry’s director of cabinet—I am back at the same roadblock. With much reluctance an unsmiling policeman lifts the metal bar for my taxi and we are sent on our way with a warning about the consequences of taking photographs at Berengo.

Several miles from Berengo I negotiate another police post. There, the commander insists I pay for two of his gun-toting underlings to accompany me the rest of the way—$20 per cop, for my own security. Upon arrival at Bokassa’s palace my bodyguards immediately withdraw camera phones and snap away. Perhaps foolishly, I do the same.

Originally a private farm, Berengo expanded to house factories—cocoa and coffee—and other family-owned businesses. Bokassa built an airport, separate residences for himself and the Empress Catherine, individual apartments for his advisers, and lodgings for the ministers of empire. Long gone, however, are the days when Berengo was watched over by an Imperial Guard of 1,000 men.

Soldiers are still on duty here, but they are not the well-equipped, Israeli-trained troops that shielded the paranoid emperor from assassins. Instead, they are ragtag, unarmed, and unthreatening. The first thing I notice after the enormous statue of Berengo’s founder are these young men in filthy shorts and t-shirts who sit listlessly in the decrepit buildings.

Berengo’s role in the CAR’s recent conflagration has been peculiar and unhappy. These “soldiers”—Christian villagers desperate for a wage—joined the Seleka at the beginning of the rebellion and were sent for training at Berengo, which was earmarked to become a military academy. Their Muslim confreres fled to the lawless north long ago.

Now, as Christians who signed up to what is seen as an invading Muslim army, their prospects in post-conflict CAR are not promising. They are stuck at Berengo until they are incorporated into a national army. Nobody knows when that might happen. Until it does, these lost boys must simply wait and make sure to catch enough rats and snakes to stay alive. Berengo’s chef du village, who shows me around the court, does not hate these Seleka recruits. He does not even blame them. Pity is what he feels. They have been left to rot by duplicitous superiors, he claims, and only cause any trouble when they get hungry and go hunting for food in his village.

The surrounding greenery has consumed most of the buildings. Those that are accessible have been looted and strewn with graffiti. Bokassa’s tomb is a tacky structure of bathroom tiling and corrugated iron. The tiny chief refers in a deferential half-whisper to “l’ex-emperor Jean Bedel Bokassa” several times a sentence while his village wilts beyond the high walls.

One final obstacle awaits me as I leave Berengo: The chef du poste has arrived and mans the roadblock at the limits of Bangui. An underling hauls me into the chief’s office.

He instructs me to show him more than 500 photographs on my camera while the offending memory card digs uncomfortably into the sole of my right foot. Visibly irritated not to have found incriminating images, the chief nonetheless confiscates my camera and summons me to a meeting with the head of the immigration police at 8 a.m. the next morning. He now insists it is illegal to take any photographs in the CAR.

After a fraught night’s sleep in my hotel, I wait at the office in central Bangui. The director is an hour late and his employees fill the time insisting that I am in a great deal of trouble. At 9 a.m. an urbane man in an expensive suit sweeps into the office; the officers promptly offer salutes. The man is uninterested in me and unimpressed by his subordinates, and he dismisses the case before him with a bored flick of his wrist. I’m free to leave, and the next day I cross the river back into the relatively welcoming arms of the Democratic Republic of Congo.