A photographer’s longterm exploration of the little-known islands of Zanzibar.

Tourists have only been visiting Zanzibar since the late 1980s, but today, they already represent the biggest source of income for the archipelago located off the coast of Tanzania. Over 200,000 of them landed on the islands of Zanzibar last year—a 14% increase from 2013. The tourism board expects that number to grow exponentially as more and more people hear about its pristine sandy beaches and vibrant aquatic life. But New York-based French photographer Ania Gruca was interested in Zanzibar’s other face. “When I saw the Zanzibar that was sold to tourists, I asked myself how people lived in such a place,” she says. “What is the real Zanzibari identity outside of the tourist package?” Fascinated by the remoteness of the semi-autonomous territory, she embarked on a longterm project that took her deep inside the culture of a little-known place. She joined R&K from Nepal.

Roads & Kingdoms: Hi Ania, what are you doing in Nepal?

Ania Gruca: I’ve been here with the United Nations for two and a half months, working for an agency that provides services in reproductive health. It’s following the earthquake, I’m here with the humanitarian response. I started working in the PR department at the UN in New York this year, which followed up with a contract in Nepal. I go on missions that last a couple of months and I work on anything that touches visual communications. Next to that, I try to work on personal photography projects but it’s not always easy because I have a lot of work. I really want to find a balance doing this, rather than working odd photography jobs in New York. This is very close to what I’m interested in because it’s on the field.

R&K: Tell me about the first time you went to Zanzibar.

Gruca: The first time was in 2008. I was traveling in East Africa and covered a story in Kenya. I stopped in Zanzibar for a very short time, a few days, and I was fascinated and surprised by how stuck-in-time and remote everything looked. I didn’t fall in love with it, but there was something interesting about the fact that it’s relatively never talked about. It’s a very mythical place, and actually people often ask me whether Zanzibar really exists. I’ve been going back and forth between New York and Zanzibar for the past five years to work on this project.

R&K: So what exactly is Zanzibar like?

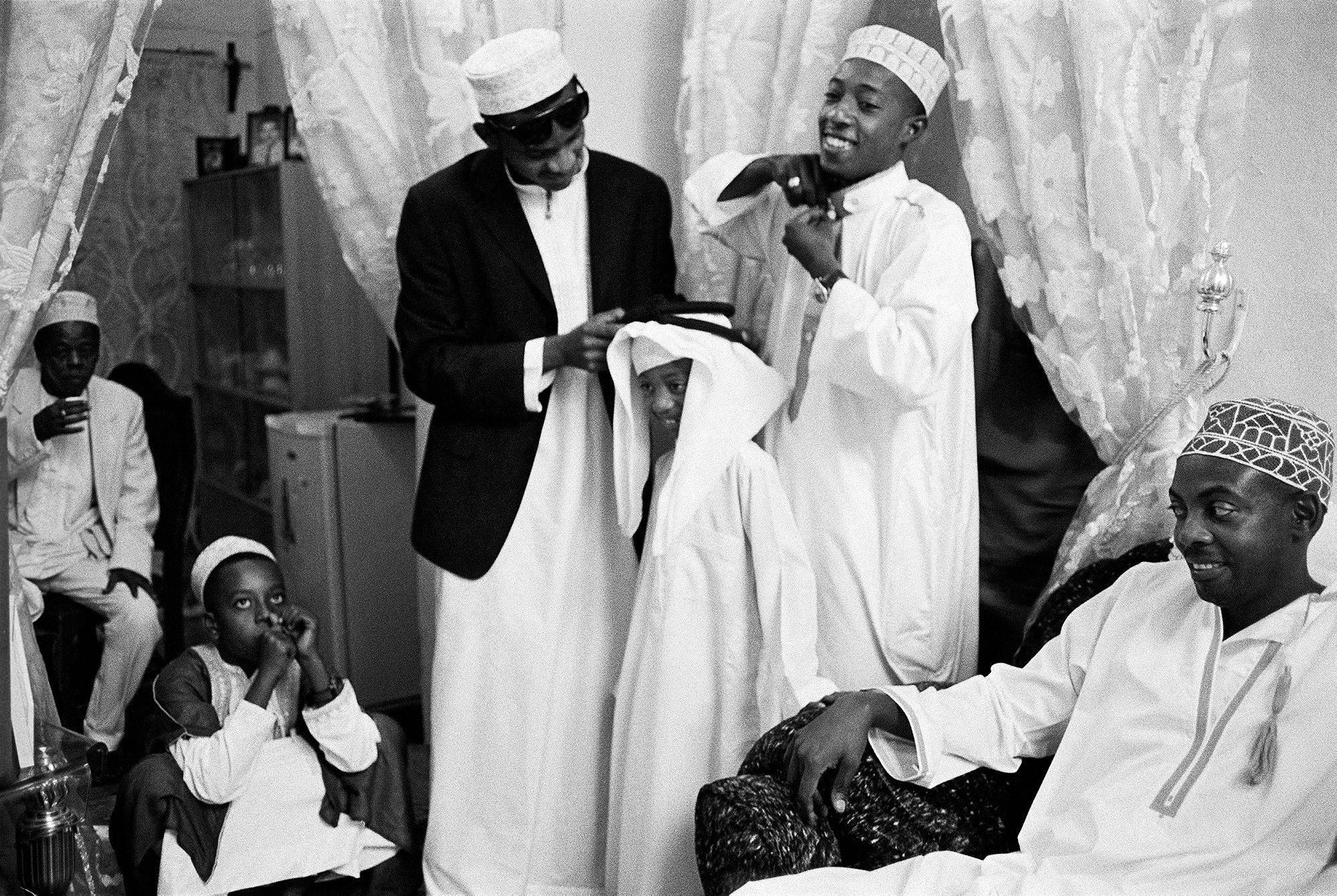

Gruca: It’s an archipelago that is politically attached to Tanzania, but it’s a semi-autonomous state. It went through several waves of immigration and has a multicultural identity based on Arab, Indian, African and European influences. About 95% of the population is Muslim. It’s also a country that is losing its cultural heritage because of globalization and the rise of very aggressive tourism.

R&K: At what point did you decide to start this project about Zanzibar?

Gruca: After my first trip, once I got home to New York, I started researching Zanzibar and I could not find anything apart from a couple of books about the revolution. There really isn’t much on contemporary Zanzibar. I thought I would go back with my backpack and I’d start a project there.

R&K: So you went back in 2010?

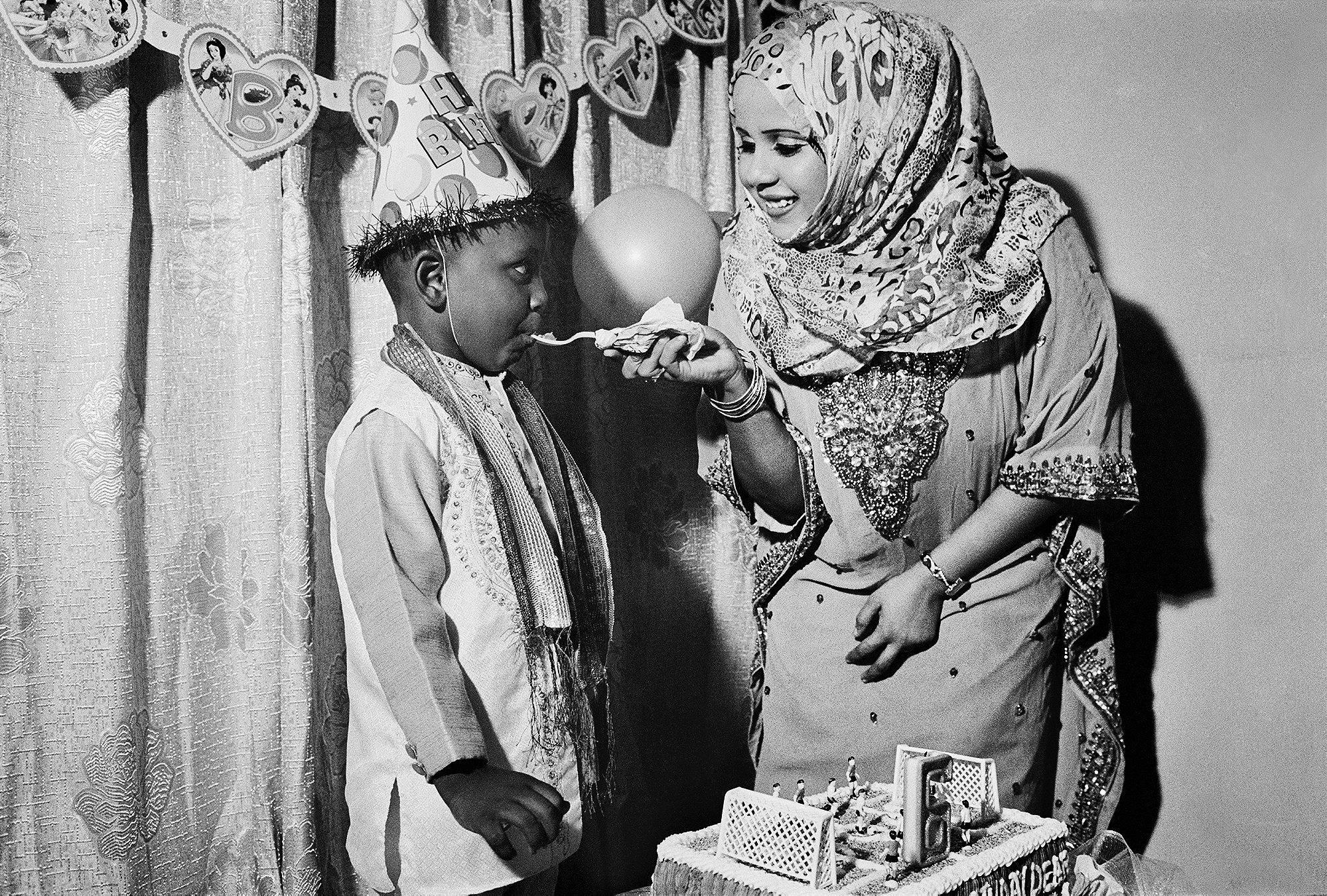

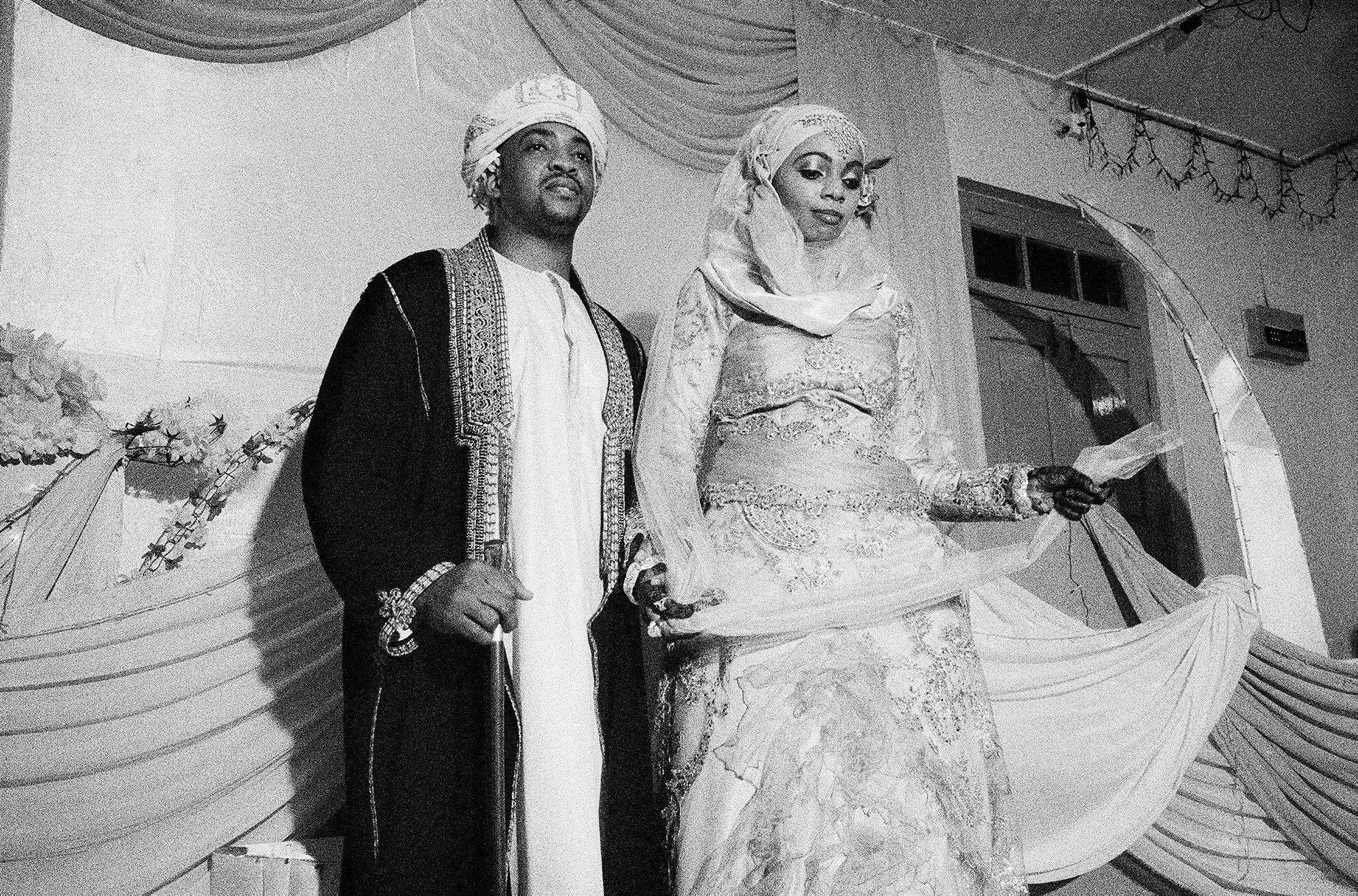

Gruca: Yes, I went back for three months. I told myself that I would first look at the youth of Zanzibar. I contacted an organization that put me in touch with a group of young people. Out of the 25 that I met, four of them volunteered to help me: two girls and two boys. I told them that I wanted to understand the culture of Zanzibar, so they took me everywhere. Little by little, I entered their family circle, they brought me to their schools, I met their professors. Then I attended celebrations, I went to weddings, and it was really a snowball effect. I went everywhere. I started approaching people in the streets, namely a group of young people who were homeless, and women who lived in sober houses. I went to a Koranic school and a professor there took me to his village. It became a constellation of contacts and of events that enabled me to spend time with people of different classes and different backgrounds.

R&K: Is that how you approached all your trips there?

Gruca: I shoot everything on film, so after this trip I went back to the US to look at and to digest the work. I went back four months later for the presidential elections. It was a really important time politically; the elections were very peaceful compared to the violence of 2005. It was also an important trip personally because that’s when I really felt like I had a life there. I started speaking Swahili much more easily and I felt really free in my movements and in my photography. I also gave a photo class, which enabled me to integrate even more with students who really became accomplices in the work and in the exploration of Zanzibar.

R&K: When did you realize the breadth of this project?

Gruca: Actually I never really thought of the length of this project. Instead I always saw myself in the present. Every time I come back from Zanzibar, I take a good look at the work to see if I need more material. For now the answer has been yes.

R&K: How have you seen Zanzibar change?

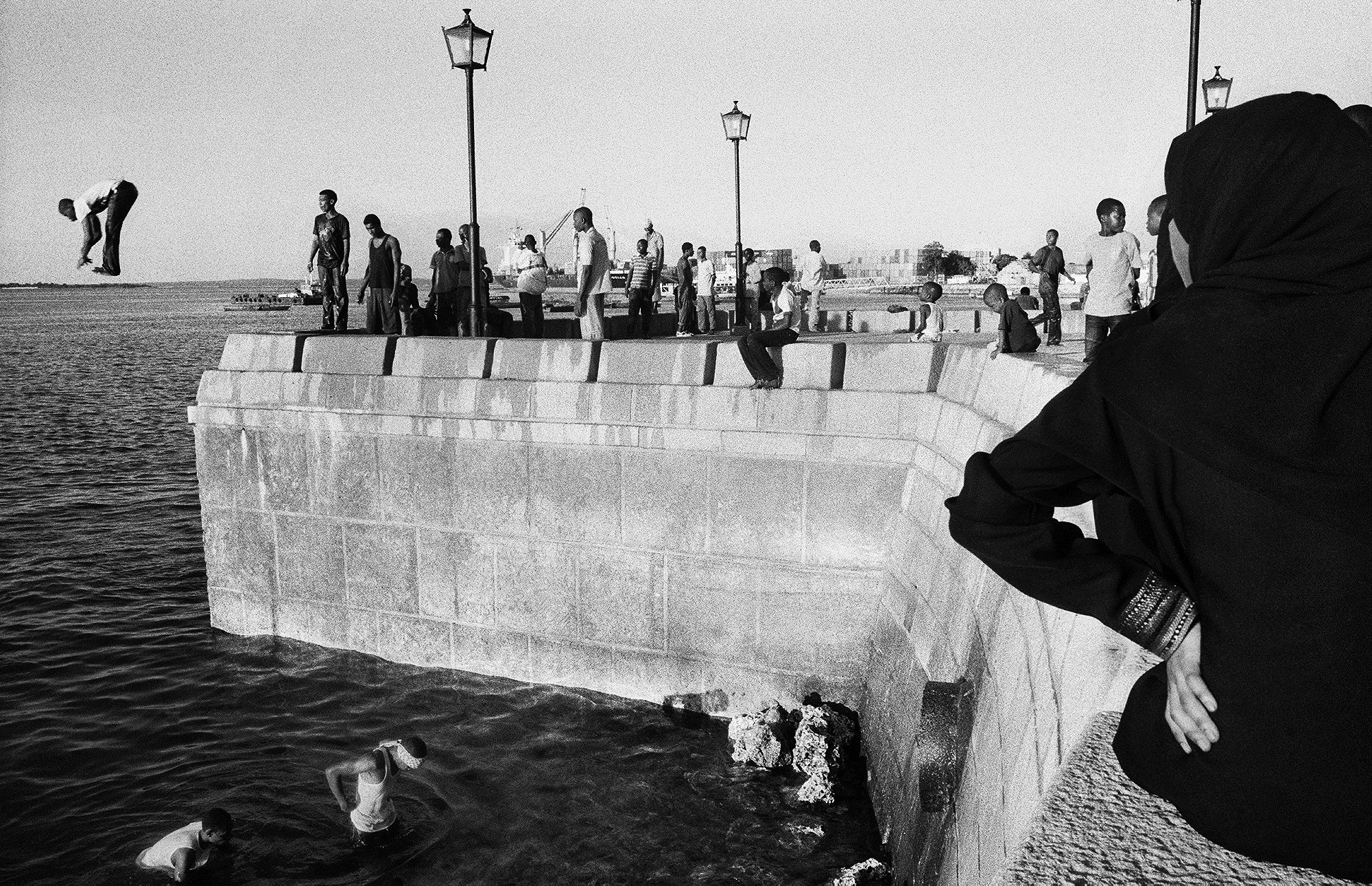

Gruca: Over the past five years, it has completely transformed itself. The impact of tourism has been huge. A middle-class has emerged, hotels have been built, the youth emancipated itself thanks in part to social media. Zanzibar really opened up to the outside world. However, the problems are still the same: it’s a divided society. One part is getting richer while the other stays behind. When you look at the upcoming elections, there is a fear that violence will erupt because there is a lot of dissatisfaction. Basically Zanzibar is modernizing, but in a really bad way.

R&K: Were you also looking at that in your project?

Gruca: My work really focuses on the traditional society, and on women actually. The Zanzibari woman is quite discreet and shy, and as Islam tightens in the country, I really tried to photograph all these women who are hidden away from much of public life.

R&K: What were some of the strongest moments for you during this project?

Gruca: I spent a night on a fishing boat with six fishermen who introduced me to the women who cultivate seaweed. That night on the boat was unforgettable. They were fishing in the dark in the middle of nowhere. I found myself in one man’s family in Pemba, which is the twin island of Zanzibar, for Ramadan. It was extraordinary. I was also invited to one wedding where I was taken from one room to the next, or I spent nights with young people who live in the streets. I had a lot of extraordinary adventures. Though I’ve kept in touch with a lot of the people I photographed, there isn’t a clear continuity in my photos. I have moved around so much and met so many families that I have many, many stories. Some characters come and go, others stay around for years.

R&K: You spent a lot of time with young people throughout the project, have their prospects changed over the past five years?

Gruca: When you look at the opportunities they have, there still aren’t many. It hasn’t changed much. Wealthy families have access to education and better jobs. Universities have been built, but their access is still very limited, same with private and international schools. There really are two worlds and the separation between the two worlds, I think, has been getting stronger. This is a personal opinion based on my observations, I wouldn’t want to be seen as a Zanzibar expert because I am a photographer. I try to see the most that I can but I’m not researching the country as a sociologist or an anthropologist would be. I do want to be careful to not make broad statements, because very few things have been written about Zanzibar and I really believe that Zanzibaris are the ones who can tell their own story.

R&K: When looking at the future of the country, you’ve mentioned potentially violent elections and growing inequalities, are you pessimistic about what’s to come?

Gruca: I don’t personally see a favorable evolution right now. I don’t see it at all. There was violence during Ramadan two years ago, there was this acid attack on tourists, there’s a French couple that was assassinated in 2014. Tourism is growing as a whole, but the country can’t rely entirely on that. The political situation is very complicated. I will have a better sense of the atmosphere when I’ll be there this month, but from the outside, and judging from all my previous trips, I am not very optimistic.

R&K: What are some of the problems that come with a tourism-based economy?

Gruca: A whole coast has been taken over by hotels, which really creates a schism between the villages and the seaside. In certain places there is even a wall or at least very limited access to the water. You’ll have places where a hotel has running water and electricity and the village next to it has nothing. Zanzibar could very well become a touristic destination, where local families will be displaced and forced to survive with nothing. Again, this is my personal perception. I don’t see what the government is doing about it. A lot of NGOs have been working to bring water and solar energy to villages, but there’s so much to do and the government is very corrupt, in part because of tourism.

R&K: What is the one thing that keeps you coming back to this place?

Gruca: There is this woman, I’ve known her for four years now. She always asks my friends in Zanzibar how I’m doing. When I’m there, I go and see her and we chat. This woman bakes and sells bread, but she’s also an activist at the opposition party. For me, that’s what Zanzibar is about. I’ll meet an electrician in the street one afternoon, and that evening I’ll run into him at a Madrasa filming Koranic prayers. It’s an archipelago with more than one million people but it still feels like a village. And I feel like I have the opportunity to meet very different people every day, which really illustrates the richness of this place.