Les Manning’s stories of adventure in the Amazon were enough to land him a spot in the famed Explorer’s Club. But the stories weren’t really his.

The Explorer’s Club headquarters fill a five-story Jacobean townhouse on East 70th Street in Manhattan. The inside looks lifted from the opening scenes of an Indiana Jones movie: Wood panels, stuffed leopards snarling, mounted expedition flags, and photographs of triumphant explorers line the walls. Founded in 1904, the Club has twenty-six chapters all over the world. To become a full-fledged member, you must “carry out or assist in field science expeditions to study unknown or little known destinations or phenomena in order to gain knowledge for humankind.”

James Cameron is a member. So are Buzz Aldrin, Sally Ride, John Glenn, Neil Armstrong, and Neil deGrasse Tyson. Membership has its perks: access to grants and lectures, the opportunity to network with moneyed members who might want to fund your next trip to Timbuktu. Presumably you’re allowed to lounge around the club headquarters, but like most exclusive clubs, membership is about prestige. To earn a place at the Explorer’s Club means you’ve done something extraordinary.

There’s no such thing as nobility in the United States, but fame and notoriety come close. My grandfather, Donald Dea McGirk died in May 2012. At his funeral, my dad, Tim McGirk, who is a journalism lecturer at Berkeley and a former correspondent, told me something very peculiar: “Did I ever tell you your grandfather had an impostor? One of his friends—a guy named Les Manning—assumed his identity and used his stories to get into the Explorer’s Club.”

Don was a willing accomplice. He gave Les Manning his tales of adventure in the Amazonian rainforest so that Manning could join the Explorer’s Club. But why? I wanted to understand the man my grandfather was, what could be so important that he would opt out of his own life story and give it to another man?

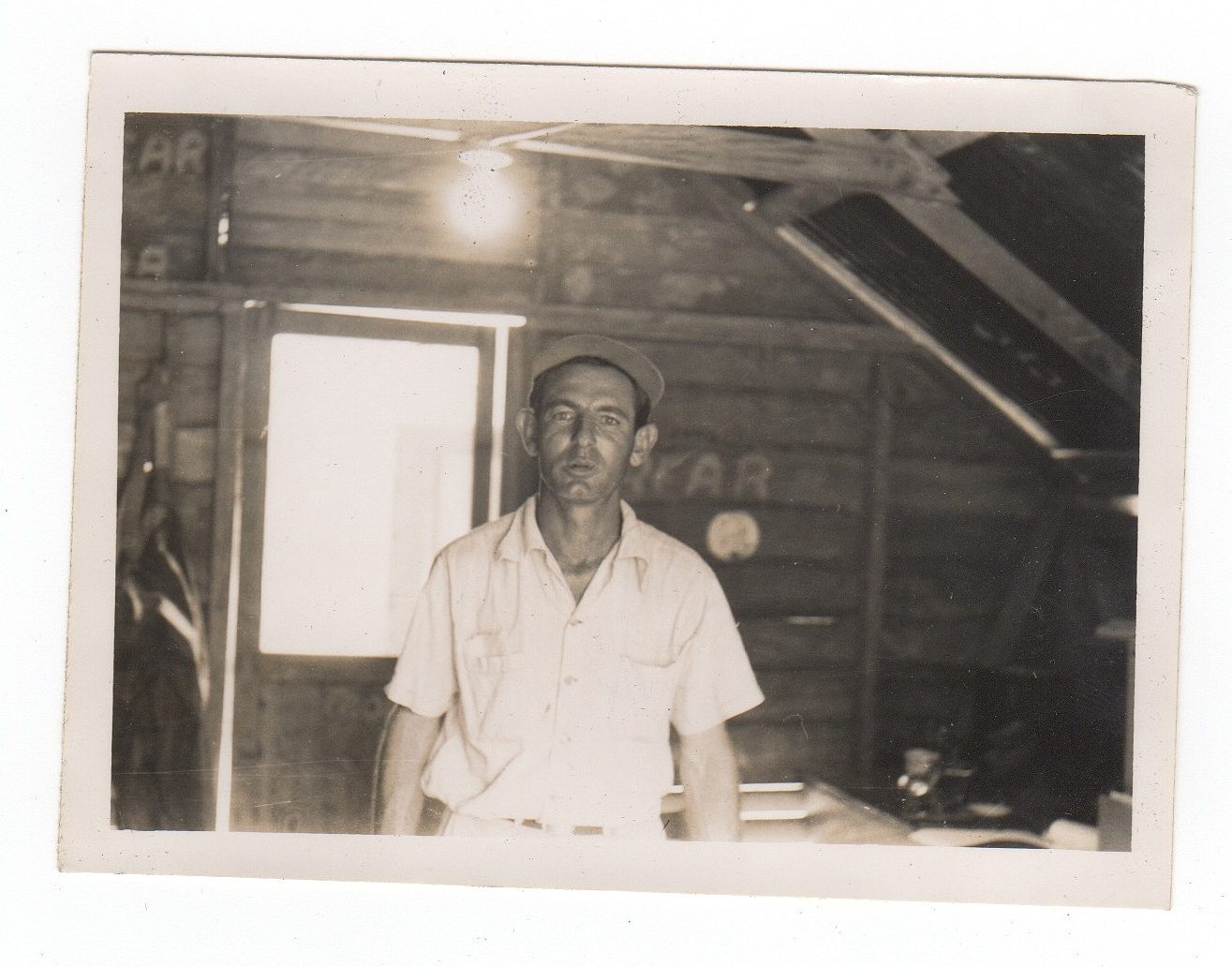

Don was a geologist, an oil finder who began his career in the Amazonian rainforest clutching a machete and a hand-cranked radio, and slashed his way into the upper echelons of the Texaco corporate hierarchy. He was born in 1917, in Huntington Beach, California, back when Huntington Beach was known as Smeltzer and California was a tough, destitute place. It was the end of the American Frontier, a hot wilderness populated with hardscrabble farmers, strange cults, real estate swindlers, and mad, desperate men who set off into the Mojave looking for gold or oil and rarely came back. His father was one of those hunters—a wildcatter, or an oilman who drilled holes all over Southern California.

Don took a more methodological approach: He studied petroleum geology at the University of California, Berkeley, and, after graduation, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, mere months before Japanese bombs struck Pearl Harbor.

Don commanded an artillery company and fought at Midway, and he refused to tell the family what he’d seen. For most men, World War II would have been enough adventure for a lifetime, but he craved more. He put in an application to what was then known as The Texas Company and received his first assignment in 1947—a jungle in the Putumayo-San Miguel region of Colombia.

The Texas Company (later renamed Texaco after its telegraph abbreviation) was like a combination of Goldman Sachs, Google, and what used to be known as Blackwater—a brainy, technologically sophisticated company that operated in the most exotic locations on earth. An entry-level position was coveted. There was good money to be made, and company men were considered a prestigious, swashbuckling bunch. The Texas Company held concessions, permission to hunt for and extract oil, in the most remote places on earth: the Arabian Peninsula, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Amazonian jungle.

Texaco had been sending geologists to Colombia since the 1920s. Not all came back. There were promising signs of petroleum everywhere: oil seeps that drooled rainbows into streams and mysterious dead zones; quiet, empty holes in the jungle canopy where all the plant life had been killed off by leaking natural gas. Next door, in Venezuela, was the best evidence of all: Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon-Mobil) found a goliath oil field beneath Lake Maracaibo. Venezuelan oil was sour, meaning it was clogged with sulfur and more expensive to produce than the light, sweet Texan stuff that was so easy to turn into gasoline, or the oceans of Arabian crude that cost pennies a barrel to pull out of the ground. But demand for oil was growing, and oil wells don’t last forever. Texaco knew there was money to be made in Colombia. It was just a question of finding the oil.

Don’s concession was deep in the Amazonian jungle, in the Putumayo-San Miguel province, which lay along the Putumayo River, nestled close to the border with Ecuador. A story about the area described a pair of French missionaries who were sent into the jungle after a missing comrade. They found him when his shrunken head was offered for sale as a souvenir.

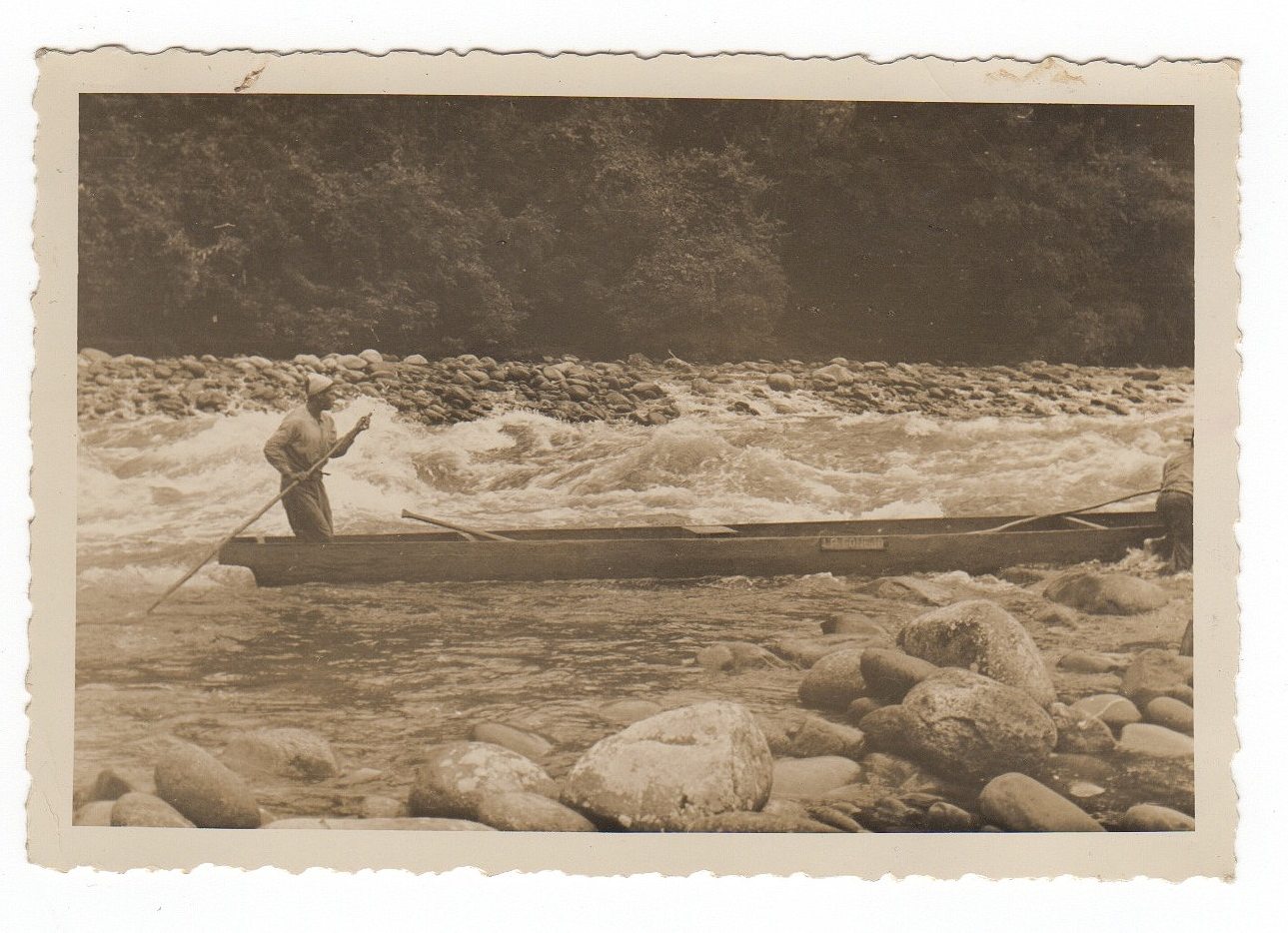

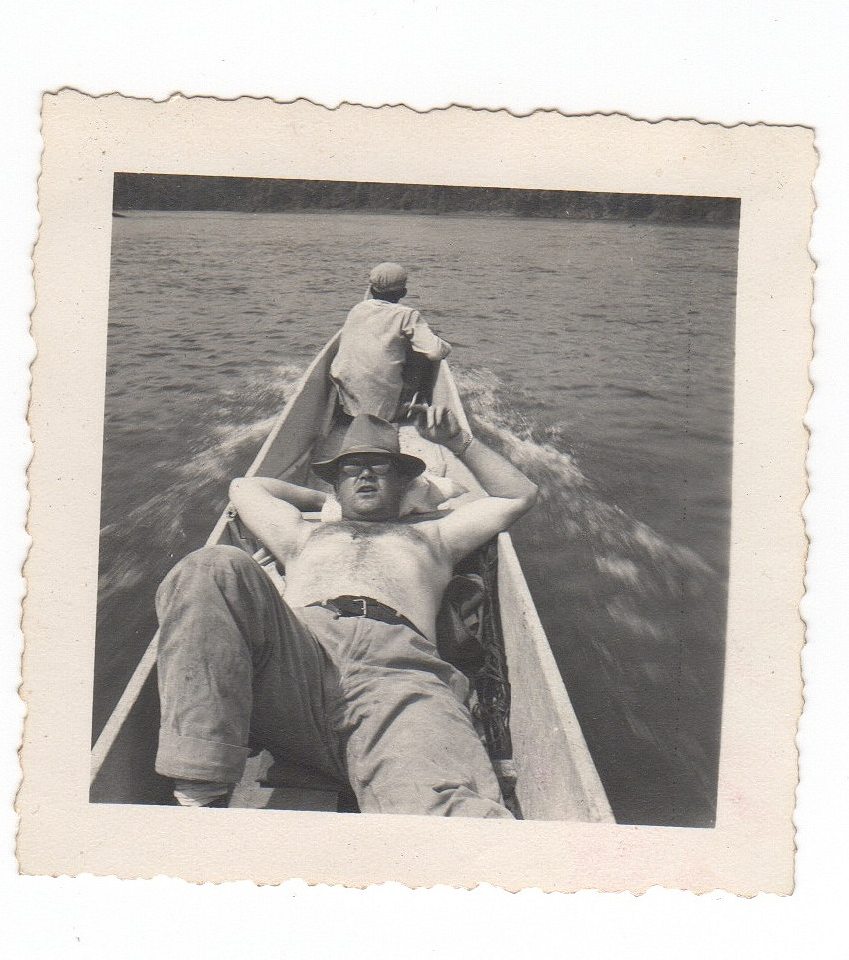

It was an inhospitable place. Don traveled to the closest town he could find and hired native guides to take him into the jungle. The only way in was by canoe. He piled his with dry goods, Scotch whisky, and ammunition and made his way up the shallow, rapid-filled river, its banks patrolled by jaguar and giant anacondas who were said to droop from branches that overhung the river and pluck men from passing canoes. The waters were clogged with caiman—dangerous aquatic reptiles that are closely related to alligators—snapping turtles, and piranha. If you dragged your hand in the muddy water to cool down, it might come back minus a finger.

By day it was dangerously hot and humid, so humid you could hardly tell if you had malaria or it was just the weather. The green smell of vegetation, of hot rot and the intoxicating bloom of jungle flowers, was so thick it was hard to breathe. At dusk, bats came streaming out of the canopy, millions of them, great formations like flocks of starling. As night fell, there was no relief from the heat and the sleepy daytime buzz of insects dialed up to a roar, and the underbrush exploded with crashes as heavy things forced their way through the vegetation, sentinel monkeys screeched and drumbeats echoed in the distance.

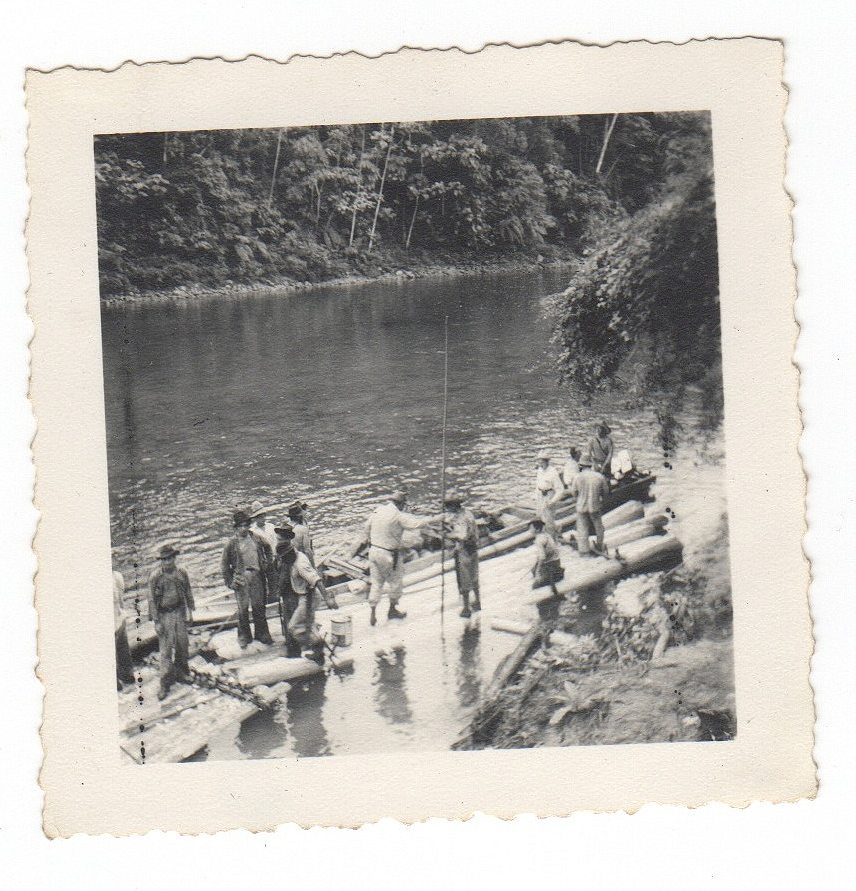

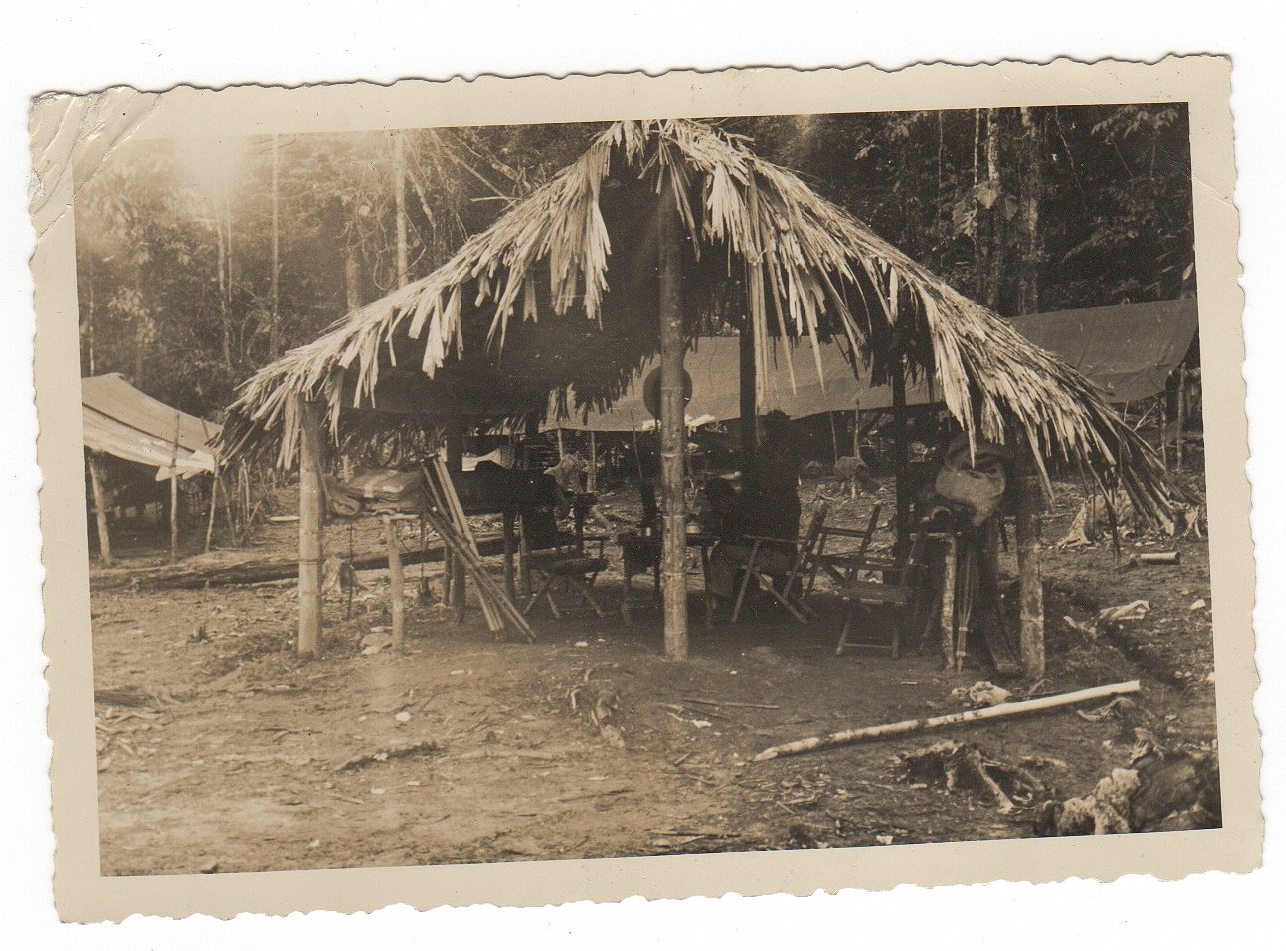

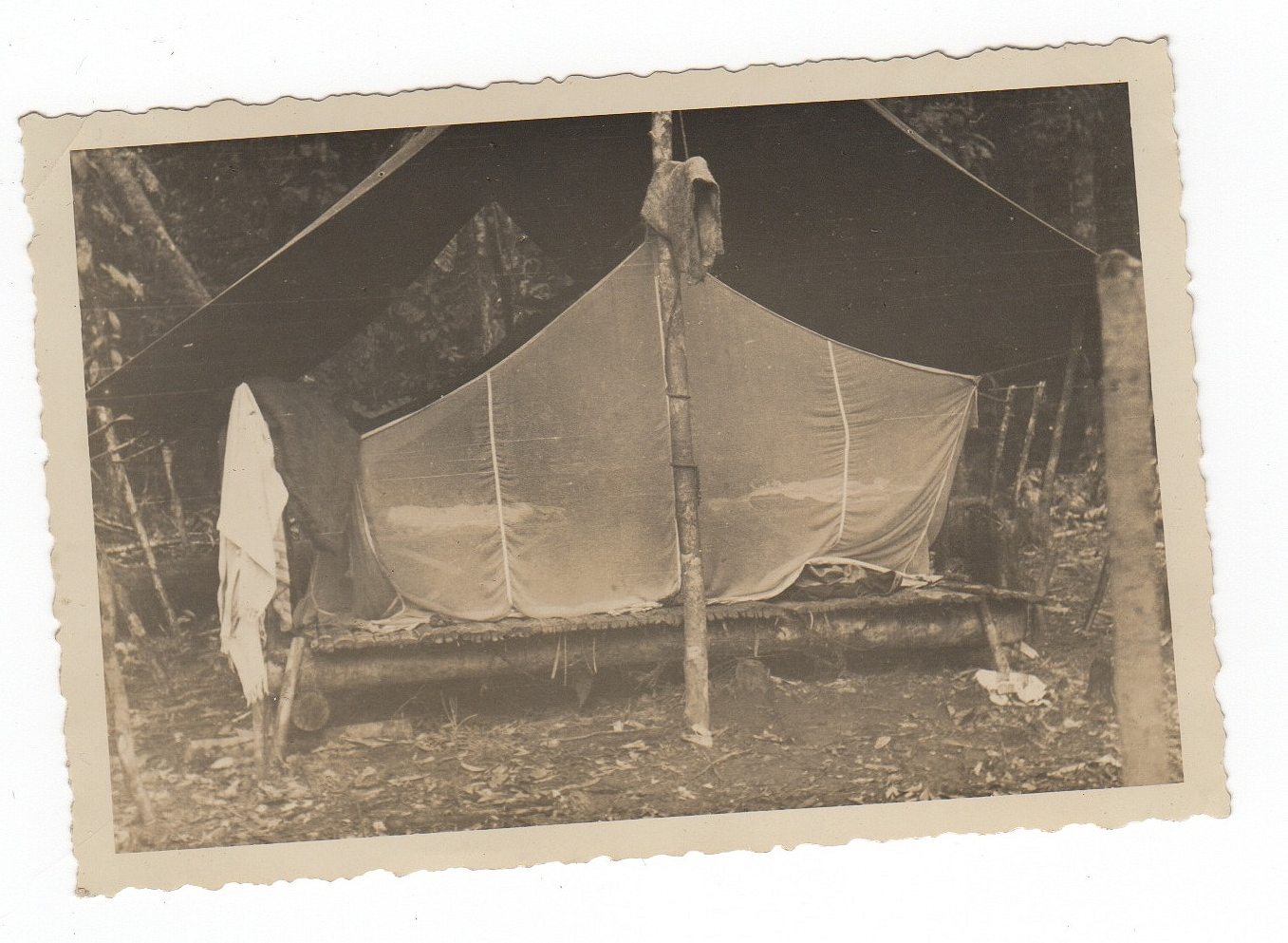

The camps were little more than outposts. Don would prowl the wilderness, surveying, the only American in a crew of laborers, trying to figure out the formations—the rocky skeleton that lay beneath the rolling green plant life above. If he found a particularly promising spot, he would summon a drill team by radio and they’d wildcat—drill a hole and grind down into the rock below.

Oil is typically found in a pocket that forms at the bottom of a geological basin, where light sedimentary rock and denser igneous rock meet. Don catalogued the grindings, keeping hefty ledgers of photos taken of the rock slivers, trying to assemble as accurate a picture of what was going on below as possible: How old was it? Were there fossils or, better yet, little bits of oil or natural gas? Digging for oil is like a gigantic three-dimensional game of Minesweeper. There’s considerable risk in drilling wildcats, but even a dry hole reveals valuable information about the surrounding area. Do you risk time, money, and the safety of your crew drilling another, or do you move on and risk missing a bonanza?

Don sliced the man’s thigh open and sucked out the poison

Camp life was torture: hard, meticulous work at a rickety desk, while sweat dripped from his brow and bugs dive-bombed any exposed flesh. He was airdropped supplies. On his first run, Don opened the crate from the quartermaster in Bogota and discovered that all there was to eat for the next two months were cans of pickled pig’s hooves. (When he returned to the city, he grabbed the quartermaster by his lapels and slammed him into a wall.) Not only were there giant anacondas lurking, there was a fearsome thing the locals called “el veinticuatro” (the twenty-four), a nasty snake whose venom would kill within twenty-four hours. One of the native bearers was nipped. Don, who had dealt with rattlesnakes at his father’s California gun club, sliced the man’s thigh open and sucked out the poison.

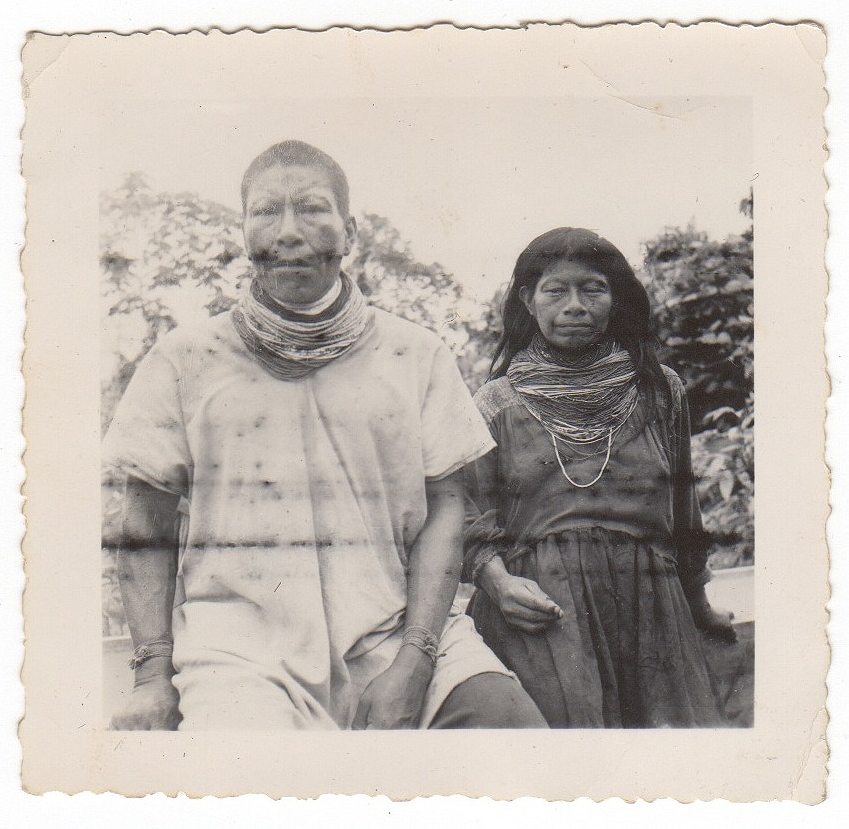

One day, while roaming through the jungle, Don ran into a tribe of brightly painted warriors: the Cofán. It was an amicable meeting. Don dazzled the chieftain with his hand-cranked radio that spat bright blue sparks. They agreed to trade: Don handed over steel implements and strike-anywhere matches in exchange for safe passage for the Texas Company and its subsidiaries. They sealed the deal by slicing each other’s palms open and smearing their blood together. For days the tribesmen cranked the radio, mesmerized by the ghostly sounds of music, while Don explored their territory. It’s not clear whether the happy exchange ever factored into later, more successful oil operations in Cofán territory (or the Ecuadorian government’s $19 billion judgment against Texaco for allegedly polluting Cofán lands and the ongoing litigation that Chevron inherited), or whether the Cofán had any idea what the sulfurous fluid the men were so obsessed with was. But for now The Texas Company and its allies were allowed to keep exploring. Don received a ceremonial headdress, a blowgun, and a bag of darts that hung in his hallway for years. The tribe’s shaman also offered him a mug of hallucinogen-laced sludge called ayahuasca, but Don turned that down, saying he preferred Scotch or a nice glass of beer.

When Don’s good friend and fellow geologist Les Manning repeated the story of the journey into Cofán territory at the Explorer’s Club of New York, he always accepted the ayahuasca.

They say taking ayahuasca is like letting the film sputtering before your eyes stay too long in front of the projector bulb—reality droops, bubbles, and melts. Time ends. Identity slides between people like fluid spilling from an over-filled cup. Age and muddled memories do that too. In 1950, just before he applied to the Explorer’s Club, Manning asked Don for permission to use his stories: “You’ll never use em, Mac,” he said. “Give them to me.”

Don donated his body to science. We’re not a religious family, so our ceremony was mostly improvised. There weren’t any guests, just my mom, dad, brother and I, the few remaining McGirks. We planted a pomegranate tree and said our goodbyes. It seemed appropriate for Don to finally put down roots after a life spent flying around the world.

When I returned home from the memorial, I phoned my father and demanded further information. How did you know Don was a willing participant? The impersonation of my grandfather was one of my Grandma Jeanne’s favorite cocktail party quips, he replied, and “on one occasion in Madrid, in the late 1960s,” Manning came to visit and he believed he “heard Dad and Les joking about it, long after the fact.”

I wanted to know more. So I read up on Colombian history and about Texaco. Dad offered to help, and wrote to the Explorer’s Club asking for information about Les Manning. There wasn’t much, just a copy of his application, which they scanned and sent back to us. Manning applied to the Club on June 2, 1950. On his application, which was approved, he was asked to list “[e]xpeditions directed, accompanied or financed whole or in part, with dates, and Applicant’s position or occupation on same and scope of exploration and results obtained.”

He wrote:

From June 1947 until June 1949 I was employed as a reconnaissance and field geologist for the Texas Petroleum Company in Putumayo-San Miguel jungle area of southern Colombia, South America. During that time I was the leader of a commission consisting of 30 to 40 native laborers and mule-men and one Colombian surveyor. I was the only American in the party… A great deal of the time I was mapping areas in dense, totally unexplored jungles. We reached my various camps by the use of native canoes as far as the turbulent streams would permit, and from there we would travel often for many days, on mule-back, through trails that were cut by men with machetes. On many occasions I encountered and stayed with Indians to whom the white race was totally unknown.

According to hand-written records, several men sponsored Manning’s membership, including a “Frank P. Lotestein,” which was probably a typo for the great geologist Frank B. Notestein. Notestein was hired in Colombia as a consultant and, according to my Grandma Jeanne, was a mentor to my grandfather.

It seemed plausible. And the more I thought about this story, the more I realized how little I actually knew about my Don. I didn’t know what came after his great jungle expedition. When we lived in Madrid and New Delhi, where my parents were stationed as foreign correspondents, my grandparents lived in London, and we would often visit. They had a mansion flat overlooking Sloane Square, in a building with an elevator with accordion doors and a dial you turned to choose your floor, and a doorman who didn’t like me. Their apartment had creaking wooden floors and hot pipes in the bathroom that would warm towels, and a human-sized statue of the Buddha they picked up in Hong Kong that sat on a rocking pedestal and at night seemed to sway of its own accord, as if it were guarding the passageway out of the guestrooms. We would spend hours sitting with them in the sitting room beneath a beautiful pair of framed feather headdresses, chatting. But it was always about our lives or the people they knew, and never about theirs. It was my fault. I never dared to ask. Don was gruff and glib, and tended to snarl at me. I wanted to be just like him.

Don retired from Texaco in 1984, and in 1998 my grandparents moved from London to Santa Cruz, California, which is the closest thing we have to an ancestral homeland. Don started losing his memory. Soon after they arrived he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and spent his final years in bad decline.

I mentioned my grandfather’s death and described what little I knew about him in a column I write. A geologist named Denise Mills contacted me. She’d grown up in the same South American oil camps where Don had been scouting for oil. Her father, Jack Mills, was alive and wanted to talk about life in the camps.

In his correspondence, Jack Mills’s description of my grandfather sounded identical to Les Manning’s application story. Denise also mentioned a story her mother told about home life in the capital city, Bogota: “[M]y dad and your grandfather I suspect were in the jungle when Colombia’s favored presidential candidate was assassinated in the main square… My mom was alone at home with my oldest sister who was only 5 or 7 months old at the time… [She described] running through the streets of Bogota carrying my older sister to the safe haven of my boss’s house, with threat of sniper fire and burglary.” Jack and my grandfather were stuck in the jungle listening on the radio as Bogota burned. This had to have been El Bogotazo—the bloody riots that broke out in Colombia’s capital city after the assassination of presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on April 9, 1948. This meant that my grandfather was in the jungle the same time Les Manning claimed to be.

I wanted to expose the impostor, but my dad balked. He’d talked to my Grandma Jeanne about Les Manning, and remembered how much she adored him.

“Tread really carefully, Jamie,” he told me. “Mom loved Les.”

I decided it was time to return to California. I flew out to San Jose, California, to access two crucial sources of information: the Texaco Archives, which were acquired in 2001 along with the rest of the company by the Chevron Corporation and stashed in the company’s headquarters in San Ramon, and my Grandma Jeanne, who lived in Santa Cruz.

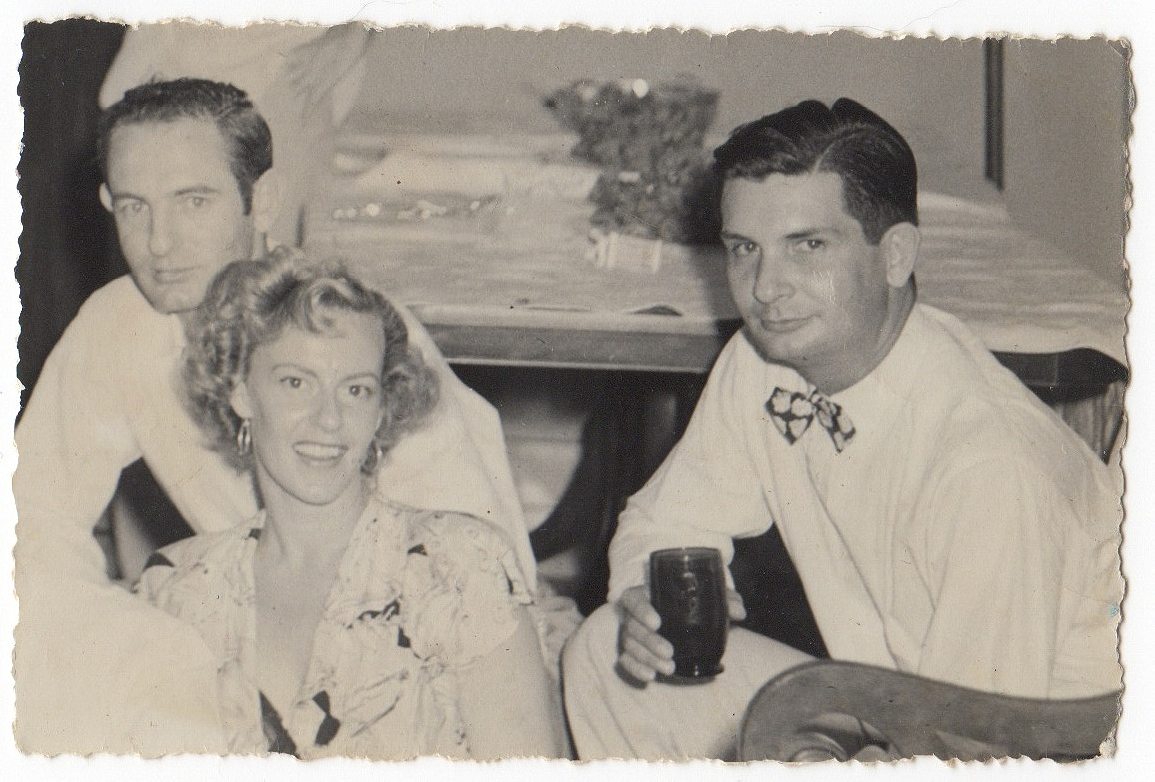

Jeanne went to high school in Los Angeles with my grandfather. They had been pen pals during the war. She worked for United Fruit, teaching English to the sons and daughters of expatriate workers in Costa Rica and Panama. Don wrote her a telegram before he headed down to Bogota: “Want to find out whether my hair falls out or turns gray?” he asked her. They eloped and were married in Panama City in 1947. Next stop was Bogota, Colombia. While Don was in the jungle, Jeanne entertained the hordes of Texaco engineers, geologists, roughnecks, and roustabouts traipsing through, and forged connections with the Colombian upper crust that controlled access to the oil concessions.

Jeanne lit up when I asked her about Les Manning. Manning was her partner in crime. He often worked with Don as a geologist. When Manning came home from the camps without Don, he would keep her company, and the two would frolic around Bogota. His hair was dark blond, she said, and he wore boiled white shirts—stiff crisp cotton worn in the style of James Bond or Fred Astaire—with their sleeves rolled up to show off his arms and their necks unbuttoned scandalously deep to better show off his signature: a tiger’s tooth necklace. He claimed that a shaman who changed from a tiger to a man as he crept through the jungle at night had given him the tooth. There are no tigers in South America, except in the circus, and it was said to be a local beast, so the tooth probably belonged to a jaguar. Jeanne got a tiger’s tooth necklace to match Manning’s. She showed me. It was yellow with age, curved like a scimitar’s blade, and about as long as my pinkie finger.

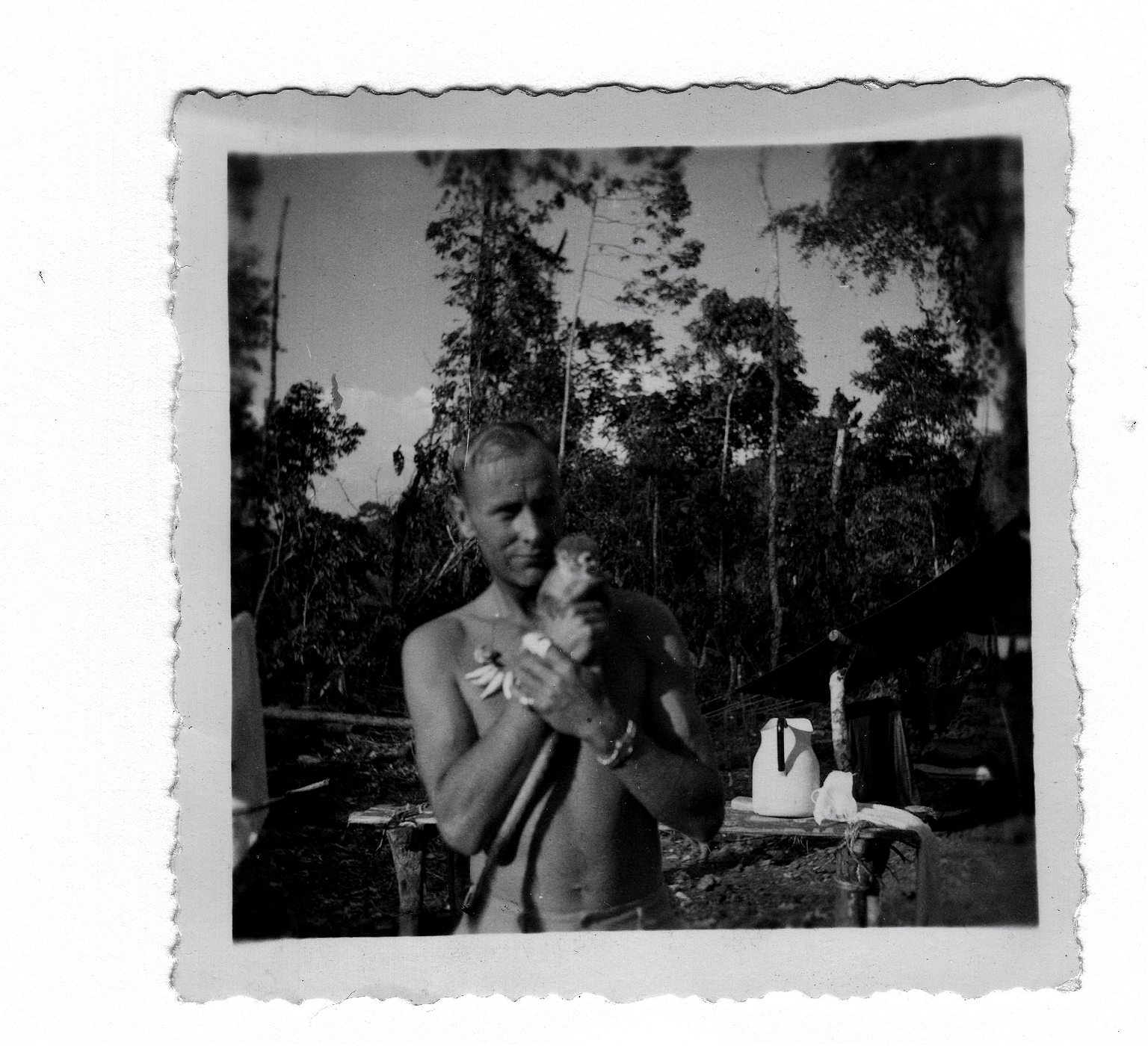

Manning was a wild companion. In a drunken frenzy, he once got himself arrested for driving cattle through downtown Bogota. During his brief stay in jail, Manning charmed the local prostitutes, and they would all call out his name as he strode through the streets. He traveled with a tiny monkey that perched on his shoulder or hid in his trouser pockets. At inopportune moments—such as while walking with Jeanne through a swank department store—the creature would squirm and wriggle out of his pants to delight or horrify whomever he was with.

Manning traveled the world accumulating Masters degrees

Like a surprising number of the men working for the great American oil companies, Manning was gay. “Many engineers were homosexual,” said Jeanne. “While Don was in the jungle surveying I would stay with the gay boys and take care of them.” Groups of engineers would roll in and out of the camps, looking for someone to confide in and take them out. Colombian machismo dictates that so long as you don’t admit to being gay (and Manning had a sort of live-in girlfriend, according to my father), it doesn’t really matter. As a geologist who went into the jungle, Manning was plenty macho. Bogota was a great place to be gay—a glamorous, young, suddenly rich city filled with political intrigue, corruption, and all the parties that such things tend to bring. Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin set to a cumber beat.

Manning was the most glamorous, witty, and entertaining of them all. “A great friend to us both,” Jeanne said. He didn’t have a sinister bone in his body. The way Jeanne described him made him seem almost vulnerable.

Jeanne was a skilled conversationalist, always eager to extract what she called a person’s “case history.” The sophisticated Manning eventually gave the young McGirks his own: Born Basil Exshaw, he was the illegitimate son of a British lord and a French actress (or perhaps a mere entertainer—that much was never clear). Due to “family circumstances,” he was adopted by an American family and later, at the age of twenty, charmed his way into the good graces of an American general. The general had “enganche,” said Jeanne, mimicking a claw. He set Les Manning (as he had decided to call himself) up with a job at Texaco and willed him a trust fund with a tricky stipulation: He was only allowed to draw from it on the condition that the money was used to further his education. So Manning traveled the world accumulating Masters degrees.

Jeanne didn’t witness the exchange. She said heard about it from Manning afterwards. I couldn’t verify what type of geologist Manning was or if he was even a geologist at all. Maybe Manning and Don overlapped the way Don and Jack Mills did, and they encountered the Cofán together, but I don’t think so. Not all geologists slash their way through the jungle looking for oil the way Don did. Manning had Don’s permission to use the stories. Assuming they were Don’s to give. What was going on?

There was no trace of Manning in the Chevron archives.

There were sixteen references to Donald Dea McGirk. They mentioned the birth of my father in 1952, Don and Jeanne’s first vacation (they stopped in Barbados en route to Don’s mother’s house in Stockton, California), and Don’s gradual ascent up the corporate ladder at Texaco. He ended his career near the top, as managing director of Texaco Orient. There were photographs, and even a brief obituary the year he died.

We found a single reference to Les Manning in the archives of the Taft School in Connecticut. He returned to academia after being accepted by the Explorer’s Club, only this time he was a teacher instead of a student. He rekindled the name “Basil” and later became the Beezer, a beloved teacher at the Taft School.

Manning’s obituary in the Taft Papyrus (dated November 22, 1985) adds exciting, if improbable, detail to his life: He piloted a B-17 during the war and was an intelligence officer for General Patton. After the war, he spent his time “exploring the jungles of the Upper Amazon, where he and his partner were the only white men. Before his time in South America was cut short by malaria, Beezer had made the largest oil discoveries on the continent. Ultimately he was elected to the Explorer’s Club for his findings.”

After exploring the Amazon, the Beezer spent twenty-three years teaching Spanish as a faculty member at Taft and another ten organizing the archives and looking after a residence hall. It seems unlikely to me that this Manning’s patron was the Gen. George S. Patton. Patton died in 1945, and although Jeanne couldn’t remember the patron’s name, she did remember that he lived in the same Upper East Side apartment building as the mother of one her expatriate friends. There was no trace of Gen. Patton having ever lived there.

Manning’s claim to have made the largest oil discovery on the continent was also wrong. The largest discovery in South America in Manning’s day was made by Royal Dutch Shell in 1914 in Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, long before McGirk and Manning arrived. But I don’t think these stories are evidence that Manning was further inflating his credentials. What could he have gained from these outrageous claims?

I think the Beezer’s teenaged elegist flubbed his stories, either that or after decades of being shared by Taft students and without Google, Manning’s stories had swollen without his help.

I also like to think that Manning’s unnamed white partner, unmentioned in his Explorer’s Club application, was a secret thank you addressed to my Grandpa Don.

It was a benign conspiracy. But why?

Don was the real explorer. By now the evidence was clear: the Cofán headdress hanging in the hall; the way he’d worked his way up the corporate ladder afterwards; Manning’s hyperbolic obituary… Don had to have been the real explorer. I have no doubt about it.

But the Beezer’s application story did have one thing going for it. To get into the Explorer’s Club you need sponsors, and Les Manning had more than the required two. If Don’s mentor Frank B. Notestein was one of them—I’m assuming there was a typo and he was—then what happened was hardly a secret; it was a benign conspiracy. But why?

As I read the archived newsletters at the Chevron Archives, I was struck by the tone. Corporate newsletters nowadays are slick and professional, their content dry and heavily vetted. The old Texaco newsletters read like a high school yearbook. It was sweet, filled with anecdotes about parties (I found details of my grandparents’ Halloween costumes and a play my grandmother directed). But it wasn’t an accurate reflection of expatriate life; there was no mention of the horrifying political violence Denise Mills described or any of the other hardships they faced. There was a reason why Don and Manning caroused when they came home from the camps.

Colombia was rough duty. I asked Grandma Jeanne if she remembered the riots that Denise mentioned, partly because I wanted to confirm the dates they lived in Colombia. At the time Jeanne was a teacher. She remembered a toddler whose parents couldn’t be reached, and how she had to take him home after the school was evacuated. “He was too scared to say anything,” she said. “He just stayed quiet.” The Bogotazo riots left the city burning for days and touched off a horrific decade-long civil war known as La Violencia. Oil camps were sacked, pipelines were blown up, and there were frequent kidnappings and murders.

I was coming to the end of my stay in Santa Cruz. My dad and I joined my grandmother for a last round of cocktails before takeoff. I wasn’t sure what I felt. Clearly Manning had permission to appropriate the McGirk family legacy. My dad had thought about the exchange too: “Don never had much truck for fancy clubs [like the Explorer’s Club] and gladly let Les, who did, borrow them as his own,” he told me. “The rascal [Manning] cheekily admitted to Dad” what he was planning to do, he said. “I think Dad was always a little pleased… at least Manning was telling them with panache, and that their shared adventures told in Manning’s voice were good enough to captivate the other explorers.”

It was a cute story and had an aesthetic symmetry to it: Don the grizzled Marine let a glamorous leading-man type assume the starring role in his life’s story to thumb his nose at the stuffed shirts in New York City, which was where the executive headquarters of Texaco were at the time (in the Chrysler Building). But something nagged. Don was drinker and an adventurer but he was no renegade. I couldn’t imagine Don pulling in a bunch of co-conspirators, powerful, influential men, just so Manning could sit around the Explorer’s Club slurping martinis and spinning yarns.

I tried to imagine what had been omitted. And kept returning to the perky tone of those Texaco newsletters I’d read in the Chevron Archives. They reminded me of the way my dad described his assignments for TIME. He never let on how dangerous they were. But once in a while something would leak out. The time he was pinned down by mortar fire in a ravine in Afghanistan. The time he looked up and saw a drone quietly circling him, deciding whether to strike.

Don let Manning use his stories. But there had to have been more to it than fun and games. Expatriate communities are small and interdependent, almost like families. I experienced it firsthand among the foreign correspondents in India. There were scrapes and freak-outs; and an unwritten code that demanded they help one another, even if someone had scooped your story or stolen your most promising prospect for a mistress or worst of all hogged the fax machine while you were under deadline. When a Financial Times correspondent’s son was kidnapped while trekking in Kashmir, the entire community flew up there for support. I think Manning needed help and Don came to his rescue.

Manning was in his forties in Bogota, and by the sound of it he had just begun his career as a geologist when he met my grandparents. Maybe Manning did come down with malaria like his obituary said (Don certainly did), or the violence got to him; or maybe Manning just wasn’t a good geologist (Chevron does not allow researchers to look at human resources records). But whatever happened, I think Manning wanted to come home. The Explorer’s Club could have been a way for Manning to save face with his benefactor and give him access to new opportunities. That he didn’t budge from Taft after thirty-three years suggests, at the very least, that his exploring days were over.

As Don began to lose his memory to Alzheimer’s, he stuck yellow Post-its on the things that were important to him. He tagged the two headdresses that hung in his hallway. There was a single word written on the note: Confán. After learning about Les Manning I wondered whether it was a last attempt to claw back his life’s great adventure or if it were garbled bit of code like the one Manning might have transmitted through his obituary to Don.

I tried to ask Jeanne one last time about Manning before I returned home. “Don and I cared about him very much,” she said. “He was a good friend. We loved him dearly.” What happened to my grandfather’s stories didn’t matter; what mattered was the friendship she, Don, and Manning nurtured for decades. In a way, for having endured Colombia alongside the McGirks, Manning was as much of a family member as I was.

Jeanne died in July 2013. To the end, she laughed as she remembered her time with Manning. We dug through hundreds of fading snapshots of her life with Don. I had recently married (Jeanne gave us her rings) and moved from New York City to the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, and this delighted her. “This will be the beginning of your own adventures,” she told me. As she lay dying, Jeanne spoke to my wife Amy: “Promise me you’ll take care of him,” she said before she slipped away.

Don and Mannings’ relationship remains a mystery. But Manning does seem more benign than not. Jeanne saw her relationship with Don reflected in my relationship with Amy, but having gotten to know her better as I wrote this story only made her death harder to endure.

I suppose it doesn’t matter why Don gave his stories away. Stories are containers created after the fact. They don’t belong to anyone.