What it’s like to live with the Italian devotee of an African death cult in Brooklyn.

This house is full of ghosts, spirits, and the souls of ancestors; gods, ancient and immortal beings made of air. They live in every dusty corner, under the tables that host the many altars, in each squeaky crack of the wooden stairs and creak of the old chairs. They live in the kitchen, in the music room, in the bedroom where Joe Black—the first black pitcher to win the World Series, in 1952—had his first child.

They are older than this brownstone, older than Bed-Stuy, older than Brooklyn and New York City itself. There is a woman who lives in the garden. Nobody has seen her, but everybody knows she is there. Tiziana brought her here, and she will never leave.

The first time I set foot into the house, I was carrying two huge bags I had brought with me on a delayed flight back from Italy. Tiziana—the landlady that a friend of a friend put me in touch with, knowing I was looking for a place to stay for a few months—is fifty, but she looks younger. She has a head of curly hair that is midway between a lion’s mane and a blackberry bush, perpetually busy hands, and a fast way of talking. She was on the phone when she came to the door and let me crawl into my room. She excused herself and disappeared downstairs, in the kitchen, leaving me alone to snoop around the living room.

Everything seemed very old and very fragile. There were statues made of wood or porcelain, boxes full of jewelry, coins and keys, candles, flags, and cloths. There was an old trumpet—a gift, I later came to know, from one of the many maestros that spent time in these rooms—and a cello, broken in half by the excitement of one of the four cats that inhabit here. There are ornaments from other cultures and traditions: Native American medallions, Hindu holy pictures, an old European straw hat. Everything was piled together, but not in a messy way. There was a reason those things were there.

“What’s all this?” I asked Tiziana when she came back. “Altars,” she answered casually as she casually told me about the ghosts. I didn’t believe her. Every sound can be mistaken as the result of some paranormal activity: one of the cats that goes for a night run, a squirrel that nibbles the branches of a tree outside the window, the slamming of a door that does not shut well. It might be unsettling at first, but once I got used to it I found no reason to lose any sleep thinking about the spirits. Instead, I grew more interested in Tiziana’s religious rites, which occupied the larger part of her daily routine.

Tiziana is Italian, and a priestess of an ancient African religion called Ifà, but better known by the name of the tribe that follows it: the Yoruba, a group of about 25 million people from southeast Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. In the new world, the religion takes a number of names and different paths from the original African cult of the dead and spirits. In Brazil, it is called Candomblé or Umbanda; Lucumì in Cuba, Santeria in Puerto Rico. Every time the cult mixed with another belief, it found a way to integrate its vast set of gods, rituals, traditions, and prayers. Santeria and Candomblé have been profoundly influenced by Christianity, which was pressed on African slaves forced to leave their homeland by Spanish and Portuguese colonialists. Almost every Catholic saint has earned a place in the pantheistic cult, their images—and, according to believers, their essences—syncretizing with the African god Orisha. Yoruba is a way to travel back to one’s origins, finding the road back home.

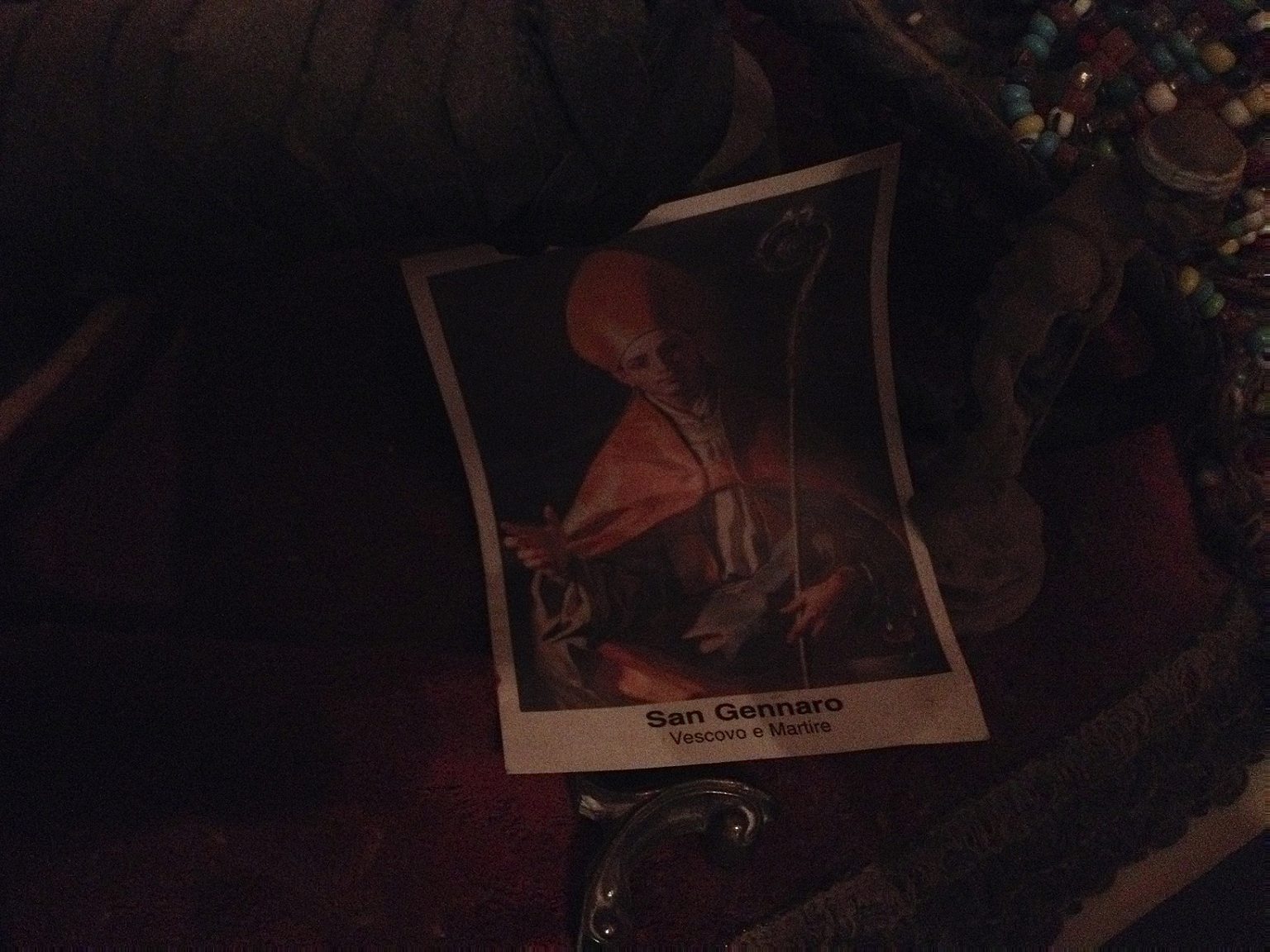

A vial of the saint’s desiccated 1,710-year-old blood is kept in a small container

Tiziana was eighteen when she left Sala Consilina—a small village in southern Italy, not far from Naples—in 1984, aiming for a new life in the United States and looking for the cult she had been reading about for years. Although she was raised in a liberal and secular environment, and not guided by the rules of a strict Roman Catholic education, she was nonetheless influenced by a strong religious tradition focused on the “mystery of faith” and a cult of saints responsible for miracles. In parts of Italy, this tradition has evolved very little from medieval fundamentalism. She was thirsty for spirituality and mysticism, and she firmly believed in magic.

To understand the profound Italian relationship with the magical aspects of faith, the cult of San Gennaro in Naples is instructive: a vial of the saint’s desiccated 1,710-year-old blood is kept in a small container, expected to liquefy every year before thousand of anxious devotees lest something terrible should occur. In 1980, the failure of the prophecy was considered the harbinger of the devastating Irpinia earthquake that killed 3,000 people. Or consider Father Pio of Pietralcina: millions of pilgrims in the far south of the Apulia region journey to witness the healing bestowed by the hands of the saint’s statue.

Or simply listen to stories about the many crying Madonnas, the exorcisms, and the unfathomable power of rites. Tiziana was fascinated by the opportunity to get closer to a cult that could bring Western monotheistic religions back to their pagan essence. She wanted to find magic so profoundly connected with nature that it has the ability to bend chance to the human will: to witch it, in the original sense of the word.

“This Earth is the place where the gods come to stay with us. There is no better one,” is among the first things Ekundayò, an old priestess from Barbados, taught Tiziana when she trained in her house in Harlem. Tiziana says it wasn’t easy for a young Italian woman to be accepted into an orthodox African house. “But Mama”—as she still calls her first spiritual mother—“had been told not to refuse a white student when she would come, and had been warned that it would be her last one. When I arrived she was very old. So she had me.”

Ekundayò always gently pushed Tiziana to rejoin Christianity, in agreement with the Yoruba principle of returning to one’s own origins, but eventually the older woman taught her how to find a new way to shape her spirituality. “I didn’t know Catholicism,” Tiziana explains. “I wanted to achieve spiritual balance, wherever that was. That was my destiny.”

Destiny is the basic concept of Ifà. It represents the raison d’être of every human being. Tiziana’s destiny was to follow Ekundayò’s guidance for four years, just to see her spiritual mother die at ninety—before finishing Tiziana’s training. It had been four years of study and self-examination, constant questioning, ferocious self-awareness, and a strong dedication to understanding this faith.

After that, Tiziana moved to another teacher: Rosa Bamgbosé, a Puerto Rican woman who lives in the South Bronx. The death of Ekundayò propelled Tiziana forward and in less than a year she was ready to be initiated as a Santera of Obatala, the Father of the Gods. After a year as a novitiate—372 days in which she had to be almost completely isolated from the world in order to concentrate on her studies—she was ready to officiate and perform the rituals that characterize the cult: sacred healing, worship of the dead and gods, and, especially, divining.

Divination is the way to talk to the spirit world. Sixteen cowry shells thrown on a mat give the priest a pattern to read the god’s words. “I may feel the dead sometimes,” Tiziana says. “But I can’t speak directly with the gods, so I have to use the mat to ask them what to do.” The divination system is extremely complex and takes years to learn properly. It is connected to poetry through a collection of parables that are interpreted in accordance with the way the cowries fall, “Like a mental dance,” Tiziana says. After the rite, some gifts are usually required to influence the course of fate and to offer thanks for the grace received. This is not that far from the offers of money and valuables made to the images of Catholic saints along an Italian procession. The gifts in an Ifà ceremony are always material: cloth, food, drinks that can be found in African markets around the city, and offerings of fresh meat that can be shared with the devotees. In Yoruba, the will of the gods is not fixed; their grace can be invoked, the gods can be appeased.

Tiziana loves music: the streets of southern Italy are filled with music with Arabian, Spanish, and Middle Eastern roots. The Taranta dance, from Apulia; the Tarantella, from Calabria; the Tammurriata, from Campania; the guttural singing from Sardinia and Sicily: each one shares similarities with forms of possession recognized in Ifà. These songs were chants of fertility, so-called pagan prayers. Among the devotees of Ifà, music is the medium for the gods to enter into the human body. They come riding the rhythm and push the priest into a dancing trance, then speak and move and feel through the priest, a vector of their mortal craving.

Every morning, Tiziana prays in the intimate space of her room, makes her offerings, and sometimes addresses the altars scattered around the house, which is where the dead live. Mama lies in a cloth bundle on a tin plate in the kitchen; Tiziana’s mother is in a porcelain pot on the floor by the door; Orisha, together with the other gods, is just outside my room. They have their favorite things with them. Their essence is believed to exist both immortally in the spirit world and on Earth, compelled by their constant will to return to the physical realm.

I saw the crowd parting, making room for the priestess

I have been living in this house for several months now, and I still don’t believe in the existence or power of the ghosts and the spirits that supposedly are my roommates and interfere with my day by day life. I lose my keys? The spirits must have misplaced them. I cannot sleep? They are keeping me awake. I cannot work? They are distracting me. Even if things go well, somehow the credit goes to the ghosts of the house. But I still cannot see them as Tiziana sees them, and the rationality I carry within me—as other Italians carry their faith—makes me skeptical. But this does not necessarily mean that they are not here.

One afternoon this spring, I met Tiziana on a very busy street in the Bronx. She wanted me to taste some cocina criolla, one of the many ways you can make good use of a chicken after sacrificing it. I started to tell her about how I missed my subway stop, found myself in a slightly scary area, and almost had to run to get out of harm’s way.

“Don’t worry,” she said, showing me the half-dozen colorful beaded necklaces she had on, covering an escapulario of Saint Michael. “As long as I have these, nothing bad could happen to us anywhere.” I am sure it was my imagination, but as she started walking ahead of me, I saw the crowd parting, making room for the priestess to go through.