Around 100,000 Sahrawis live as refugees in the Algerian desert, dreaming of the day Western Sahara will be theirs again.

Some call it Africa’s last colony. Western Sahara, annexed by Morocco shortly after Spanish colonists began to leave the region in 1975, has seen a large part of its population pushed out to a harsh corner of the desert across the border in Algeria.

Relegated to tents and mud houses, roughly 100,000 Sahrawis live as refugees in the neighboring country. They depend on humanitarian aid for everything and are separated from their homeland and relatives by the longest continuous minefield on Earth, a huge sand barrier called the Moroccan Wall. On this side, the Sahrawi rebel liberation movement called the Polisario Front is in charge.

But unemployment and growing disillusion that a referendum on independence promised by the United Nations 23 years ago will ever occur are pushing a growing number of young exiled Sahrawis into Islamic extremism. With its porous borders and vast stretches of sand, the region is fertile ground for carrying out attacks and kidnappings.

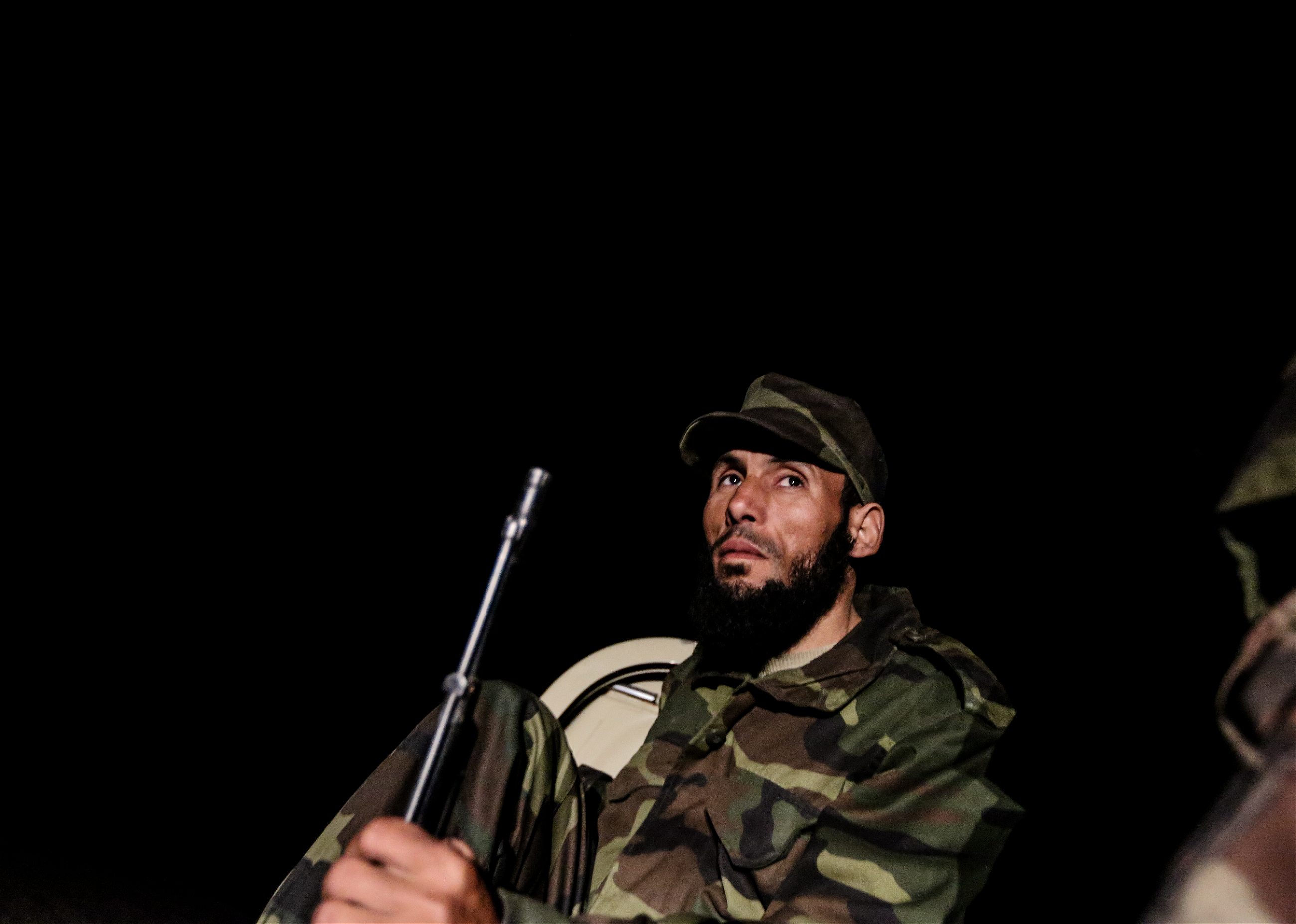

Today, the Polisario and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Army, are fighting on two fronts: one with Morocco, a conflict that seems without end, and another with the Islamic terrorists that threaten the fragile community and the stability of a region that, according to many analysts, could soon become a new theater of the global war against terrorism. This year, Polisario’s patience seems be running out.

I spent a few weeks with the Sahrawi People’s Liberation Army. From their army bases scattered around the desert where they conduct anti-terrorist patrols, military exercises, and parades, to the homes of families living as refugees in Algeria, I photographed an exiled population that, four decades on, still dreams of a nation of their own.