The Syrian cartoonists who live and die by their pens.

Akram Raslan’s illustrations from Syria tend to take place in a country with a cloudless sky. A white circle is used to frame the action, which often features President Bashar al-Assad with enormous ears and a pickle for a nose. It’s an irrepressibly homey framing device that draws the viewer into horrorscapes of bloody corpses, devastated cities, and venomous animals. It’s jarring, like a nightmare infecting an innocent scene.

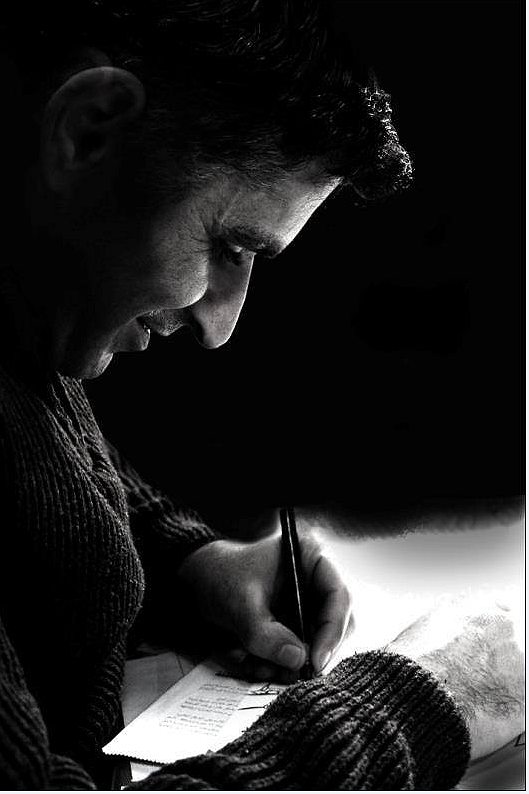

In October 2015, Raslan was confirmed to have been killed by Syrian police. A pseudonymous fellow prisoner said that Raslan died in a prison hospital, possibly after torture. It had been three years since he was first taken into custody and four since the Syrian civil war began. Raslan had been one of Syria’s best-known cartoonists before the war began. His colorful, almost optimistic scenes mocking corruption and senselessness set his work apart from his colleagues’.

Syrian cartoonists, such as the world-famous Ali Farzat, a classically trained artist with a leonine beard and mantle full of awards, made their mark with pen-and-ink drawings relying deeply on puns and requiring a bit of meditation on the work from the reader. Raslan’s style was more straightforward, almost insidious.

Both Raslan and Farzat had been arrested by the Syrian government in 2011 for their anti-establishment work. Farzat had had his hands broken by masked gunmen in 2011, making headlines around the world, but perhaps his age or international fame helped him escape with what he was told was “just a warning.” Raslan was less fortunate, having been last seen bedridden in a hospital in the northern Syrian city of Hama in 2012. He was captured shortly after the initial, optimistic waves of protest against the regime swept the city.

“That guy is fucking brave,” says Waseem Marzouki, a Syrian artist and animator, from his home in Doha, Qatar. He speaks of his colleague as though he were still alive. “I hope my English is good enough to tell you how brave he is.” Compared with Ali Farzat, who was a graduate of Syria’s best fine arts school and had connections within the Syrian state, Raslan was just a “normal guy” with a pen, Marzouki says. “You can’t judge his technique. You can’t compare it with his bravery.”

Marzouki does not use the word lightly. “Syria is currently one of the most dangerous places in the world to work as a journalist,” says Jason Stern of the Committee to Protect Journalists, who had been following Raslan’s case. Stern’s task has not been an easy one. “Since [Raslan’s] arrest, there’s been basically zero information about him.” There were reports that Raslan was executed after an unrecorded trial in 2013, but little definitive proof. The Raslan family did not want to accept the man’s death for two years, but independent Damascus-based publication Our Syria published confirmed reports in September. “We probably will not get any definitive proof” of what happened to Raslan, Stern says. But Stern goes along with many journalists throughout the region who accept that Raslan was killed and tortured in a Syrian prison system that Stern labels “nothing short of horrific.”

There is something both tragic and frustrating when someone such as Raslan is killed in a conflict like the war in Syria, which often seems to take place in a context beyond understanding. Researchers like those at Bellingcat, a citizen journalism publication, or writers like at Our Syria can do a remarkable job bringing information to the world, but it is in many ways the role of a cartoonist to bring emotive weight to events as enormous as the Syrian civil war. Raslan’s darkly humorous, almost sarcastic drawings showed the violence from the perspective of someone who dared to have optimism. Raslan’s sunny skies don’t just mock the Assad government that still gainfully employs a minister of tourism, they mock the optimism that many Syrians had in the moments before gunshots cracked through an anti-government protest on March 15, 2011.

Even before the war broke out, Raslan had made a name for himself for what Stern calls a “constant willingness to push those red lines” in Syrian society. He learned from the example of Farzat, who had received death threats from Saddam Hussein, awards from the Netherlands, and reportedly even laughs from Assad himself. Raslan also came from a peculiarly Middle Eastern school of artistic argument that altered techniques borrowed from French cartoonists in order to fit a Syrian political scene.

Cartoons came to Syria at the end of the 1800s along with cheap print and a global consciousness. This era, often called by its French name of fin de siècle (“turn of the century”) was a time of discovery and opportunity, as marked by the fantastically illustrated stories of Jules Verne. Surreal and humorous depictions of the contemporaries were not only imported from France. Molla Nasreddin, a modernist Azeri magazine that mocked Muslim clerics and feckless bureaucrats, was also popular in Damascus and Aleppo. French-speaking Syrian and Lebanese artists replaced the broad satire they found in foreign publications with sharper fare. Al-Dabbour, based in Beirut, was founded in 1922 to take local politicians down a peg or two. Many socialist groups took to the new format, finding its crude imagery and cruel jokes fitting for a message of disdain for the global order.

That is not to say that the only role of cartoonists was to poke at the state. “Comics in a variety of forms—dissident and conservative in political perspectives—have been a mainstay on the Arab press,” says Jonathan Guyer, a fellow at the Institute of Current World Affairs based in Cairo who studies Middle Eastern cartoons. Guyer points to 1930s-era magazines like Al-Fokahathat mix both Cairo-centric jokes about arranged marriages with a “jokes of the world” section that includes an assortment of obviously copied illustrations.

But by the end of World War II, a sort of global satirical medium became understood. French weekly newspaper Le Canard enchaîné became a gold standard, mixing investigative journalism with cartoons mocking the rich and well-connected. Le Canard enchaîné inspired many aspirational cartoonists in the 1970s. Two Frenchmen took the illustrations and scrapped the investigations, founding Charlie Hebdo, the satirical newspaper at the center of a deadly attack by Islamic extremists earlier this year. A thousand miles away, a Syrian began to draw at state-owned daily Tishreen.

Ali Farzat was the golden child of Syria’s cartoons. Beginning his career at the government-controlled newspaper Tishreen in the 1970s, Farzat’s work won awards and was syndicated as an authentic voice from the Middle East in the French paper of record, Le Monde. As Syria found its footing after the Cold War, Farzat was given permission to publish his own periodical, Al-Domari, in early 2001. It was the first independent publication in Baathist Syria.

Al-Domari lasted two years before it was closed by Assad’s government. It was cut so quickly that Farzat saw the writing on the wall. He continued to work in Syria, but by 2007 Farzat gave interviews warning that “the regime is in need of total reform and change.” That same year, Waseem Marzouki graduated from Damascus University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. His final project, a retelling of Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, came to the censors’ attention because “Ali” is a traditionally Shiite name. They feared that Marzouki was using the medieval legend to criticize the Assad government’s alliances with Shiite powers Hezbollah and Iran. He wasn’t allowed to present the project and soon left Syria for graduate school in California.

WE SHOULD HAVE MENTIONED OUR NAMES, WE SHOULD HAVE BEEN HALF AS BRAVE AS HE WAS. BUT WE DECIDED TO BE SCARED AND AFRAID

Marzouki was abroad when the civil war broke out, even as it began in his hometown of Daraa. He was in touch with artist friends—though not Raslan—on how to operate in the violent climate. Work was shared and critiqued via professional networks, reliant on trust. “I don’t think there was a cartoonist or comic artist with the regime,” remembers Marzouki. “That would be a disaster for us.”

These cartoonists, then, operate in a liminal space. They publish their work for a global audience, but many cannot sign their art for safety reasons. According to Marzouki, “it is a public art, not just an art for your enjoyment.” Citing Facebook outlets like Comic4Syria, he notes that “very few of these online publications had signed work. We should have mentioned our names, we should have been half as brave as he was. But we decided to be scared and afraid. Something might have happened to us and to our families.”

Raslan was one of many Arab cartoonists who had, in Guyer’s words, “cultivated diverse global followings.” Many of these cartoonists took advantage of Facebook to share and trade their works, intellectual property be damned. These artists used social media less to go viral or to make a fortune and more to get arguments that established magazines would never publish out into the world.

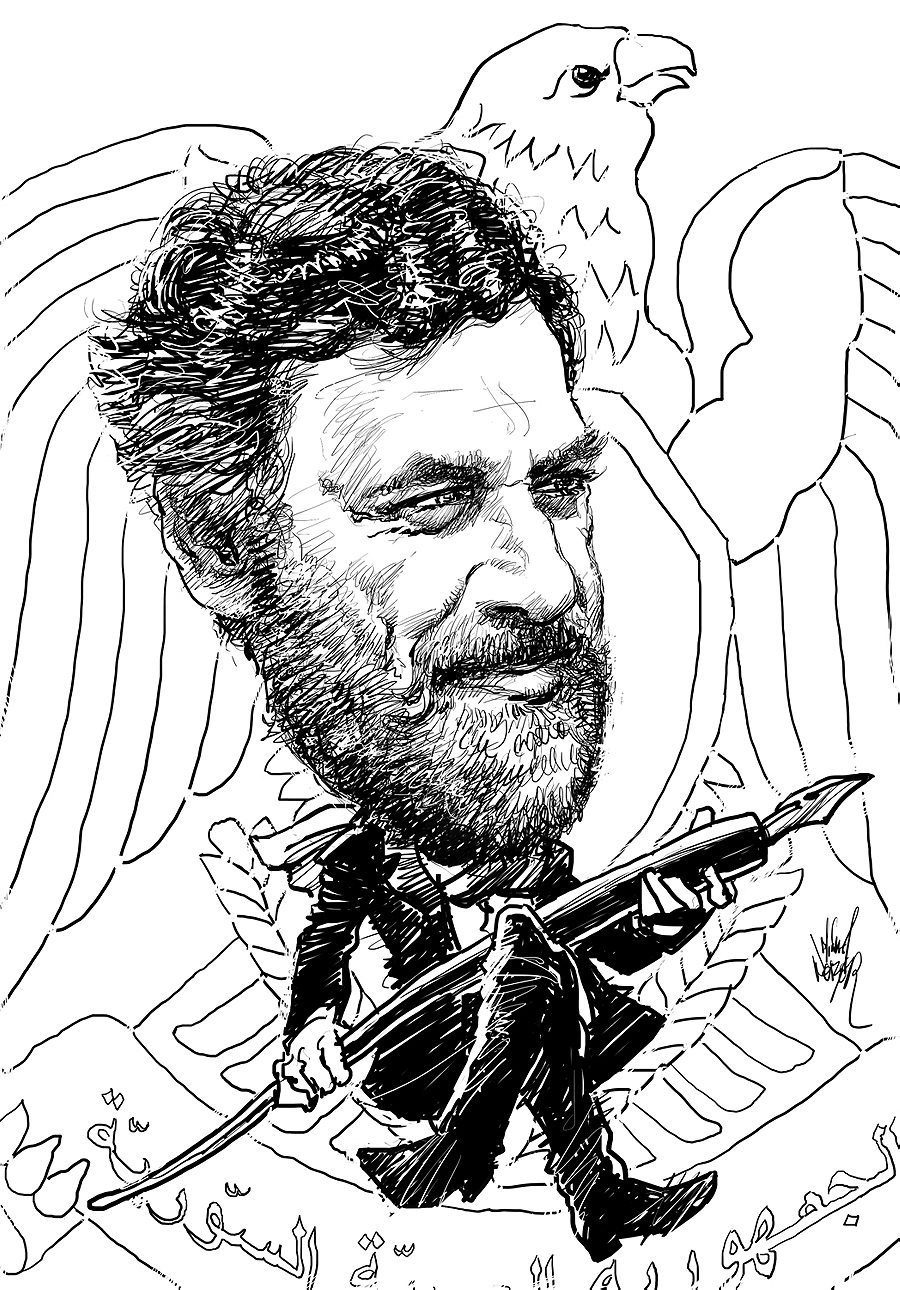

Most Syrian artists, according to Marzouki, thought that the violence would be over soon, “that it would be quick like Egypt or Tunisia.” More than four years later, Marzouki is still waiting, and it is too late for Akram Raslan. When Raslan was killed, the world gave back. On Oct. 18, Our Syria brought a satirical journal named Akram Raslan into the world. Its first issue featured Raslan’s signature over a simple red dot on the cover. Sixteen cartoonists and one journalist, mostly from Syria but also from Jordan, Palestine, and Egypt, contributed to the publication. Most of the illustrations either mourned Raslan himself or reveled in the power of a cartoonist’s pen. (The issue can be read online in PDF form, hosted by Souriatna.)

The periodical seems at first like a slapdash mix. It is clearly intended to be printed out and read by hand, or maybe shared at a coffeehouse or Pages, the Syrian bookstore in exile in Istanbul. On the other hand, the sheer vitality of the work begs to be shared online. Arresting images of Raslan wearing a crown of pencils or as a writing instrument-cum-Superman can be saved with a simple screen capture.

Raslan may have been able to flee Syria like millions of his countrymen. Ali Farzat is now based in Kuwait and countless others have found homes in Turkey, Jordan, or even France. Raslan remained in Hama, Syria, where—as the periodical bearing his name puts it—he died a martyr while being tortured.

Marzouki only began speaking publicly after his family was able to leave Syria. However, many Syrians abroad are still under pressure in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan. “The only safe place is Europe now for Syrians,” he says, before remembering Europeans’ growing hostility toward refugees in response to the Nov. 13 attacks in Paris. “So now it looks like there is no safe place.”

Any haven would be too late for Akram Raslan, whose name now graces a magazine that acts as a eulogy. It is a haunting toast to a man who, a year into the Syrian civil war, seemed so sure of his ability to bring change to his country. Few changes since his death have been for the better, and it is hard even for an optimist to imagine Raslan’s pristine blue skies showing up again anytime soon over Syria.

Cover image: A cartoon by Akram Raslan. Courtesy of Akram Raslan Magazine.