Dignity Is a Small Price to Pay for a Story

Dignity Is a Small Price to Pay for a Story

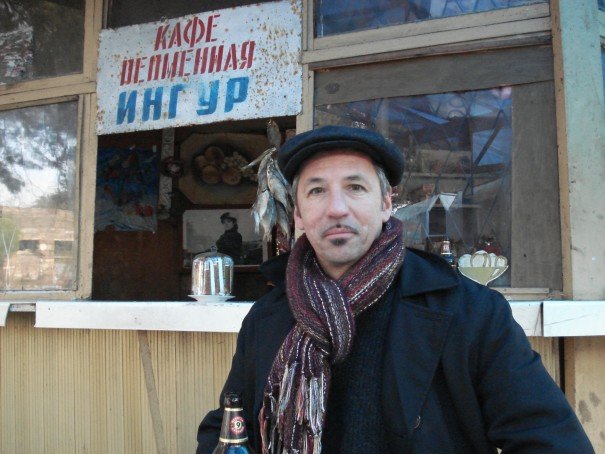

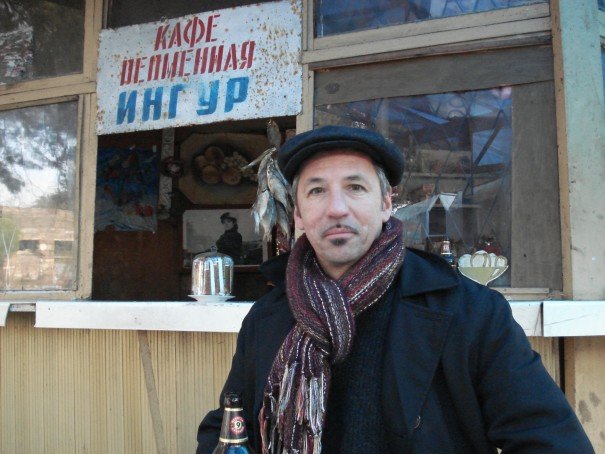

Chacha in Gali

I was in Georgia’s breakaway territory of Abkhazia for a story about the language rights of the Georgian population. Children were being taught in Russian and not their native language and I needed to talk to the minister of education, but she had evaded me for three days. Without comment from the ministry I had no story, and nobody to pay the expenses I chalked up. I really needed this story.

I left the capital city of Sukhumi’s gloomy December drizzle despondent, but not defeated. I had one last shot: Beso, the one person who could fix this for me. I just had to head to Gali, a purgatorial dominion of Georgians living in an apartheid state. Some 98 percent of Gali’s population are ethnic Georgians, but they only hold marginal positions in the administration and police force and are not allowed to vote. Beso, a Georgian, is an extremely resourceful and well-connected guy. He picked me up with his brother-in-law and took me straight to the house of the district’s education chairman. I waited in the car while Beso explained the situation from across a wooden fence to the Abkhaz official, who was wearing baggy, gray work clothes and muddy rubber galoshes. The body language did not look good.

“He said he cannot give you an interview without permission from Sukhumi, but he’ll say hi,” Beso said.

The education chairman, Daur, was leaning on a shovel and offered me a handshake without a smile. His front yard was an orchard of persimmon trees, the ripe yellow-orange fruits a fine contrast to the gunmetal sky. “Nice persimmons,” I said. “Do you make chacha from these?” While the Georgians and Abkhaz have property and political differences, one thing they share besides the word for moonshine is the tradition of hospitality. Daur glanced up at his fruit, then at me, and dragon exhaled through his nose. He opened his gate and invited us in.

Daur apologized for not having more to offer us. His wife, he explained, was visiting a relative. Daur arranged a basket of stale bread, a plate of stinky cheese, a bowl of sliced persimmons, and a second-hand plastic liter bottle of chacha on a table covered in a plastic table cloth with a cherry motif. He filled our glasses and made a toast to our gathering and we knocked them back. It wasn’t bad stuff. More toasts from the standard checklist followed—to peace, to our wives, to children, to friendship and so on—but I was the only one matching Daur, who was becoming more fraternal after each toast. Beso’s brother-in-law was absolved from partaking because he was our driver, while Beso carefully slowed down until he was just sipping.

At one point, Daur and I became Vakhtanguri brothers, which is the ritual of draining your glasses with your arms linked. This is followed by a kiss on each cheek. Then he invited me to his office the next morning for an interview. There was lots of love at that table. Things, I thought, were going quite well. I recall leaning over to Beso and remarking how drunk Daur was getting. “Ha! Ha! Isn’t that funny?”

When I opened my eyes I saw a ceiling and two children looking down at me, mystified by a drunken foreigner lying on their kitchen floor. This display of bad manners was definitely not good; horrific, actually. Where was I? “Sorry,” I said, then blacked out again. The next time I opened my eyes I was on a couch in a living room with a family around me watching television. Who are these people? What time is it? What day is it? I sat up, brushed my thighs and smiled. “Hi, I’m Paul.”

Beso had dropped me off at Zura’s house. Zura had fleeced me for what was supposed to be a loan of a couple hundred bucks a year earlier. He used that money to buy a very old Niva, which enabled him to get a job with an international aid organization. Zura said he would give me a ride to Daur’s office but first I had to help him push start his Niva, which could only be done with the gear in reverse. Hungover and cotton-mouthed, I helped him push that heap of iron along the muddy, pot-holed street for an hour until he gave up and found somebody with a tractor to pull him.

I was waiting for Daur outside his office when he came in. He had shaved and changed his work clothes for a rumpled green suit and black loafers. “How are you?” I asked. “Been better,” he said. “And you?” He unlocked his door and invited me to sit next to his desk. He eased into his seat and said with a shrug, “I can’t give you an interview. I still don’t have permission from Sokhumi.” The agony of defeat sunk deep and pinned my shoulders down to my knees. I was too dehydrated to cry, too weak to beg. “But I’ll call them now and get it,” he said smiling.

And that is how I got my story.