As a child, Marcio Pimenta wondered about the men working in the sugar cane fields near his home in eastern Brazil. Thirty years later, he decided to photograph them.

When I was 10 years old, I would cross the roads of the Recôncavo Baiano region of Eastern Brazil, traveling with my parents from the state of Bahia’s capital to a small farm where we used to spend weekends. Between January and March, the smell of burning in the sugar cane plantations indicated we were nearing our destination. As we would cross the beautiful Imperial Dom Pedro II Bridge, inaugurated by the Emperor himself, I would watch men, black with soot, cutting down or carrying large bundles of sugar cane. I had no idea who they were.

In January 2015 I returned to the region to visit my parents. Childhood memories came back as we traveled through the long stretch of land that skirts the Todos os Santos Bay, the second largest in the world. We crossed the imposing bridge and I gazed at the landscape contrasted between the green sugar cane to be harvested, and the grey soil where the burning had occurred. The men seemed to be the same ones I had observed in my childhood. I decided to meet them.

The Recôncavo is frozen in time. In many ways, it hasn’t changed much since thousands of slaves were brought from Africa to work in the lands of the new Portuguese colony. Many of the workers I met are their descendants. Some are quilombola—their ancestors were slaves who had escaped from the plantations and founded their own free settlements. Today, the working conditions of the sugar cane workers feel sadly similar to the exploitations of their ancestors.

It was on this land that sugar cane became one of the main pillars of the Brazilian economy. Today, the country is not only the greatest producer of cane, but it also ranks first worldwide for the production of ethanol. It’s increasingly conquering global markets with its biofuel industry and is also the leader in the production of two sugar cane by-products: sugar and a spirit called cachaça, the main ingredient for caipirinha, Brazil’s national cocktail.

When I first met the sugar cane workers, the earth was burning under my feet. It was 100°F but felt much hotter. On the ground, pieces of burnt sugar cane were being cut by three men. They welcomed the distraction; they had been cutting cane since five in the morning without a lunch break. “We earn by production, so it is better to continue working directly until 4p.m. After that we rest, and tomorrow we start again.”

Their work requires repetitive movement under the sun and heat, in the presence of soot, dust and smoke, for periods varying between eight and 12 hours. There are no fixed wages. They said they receive up to $30 per day, but to reach that amount, they need to cut down an average of 15 tons of sugar cane. This unsustainable rhythm often results in death due to exhaustion, cardiac arrest, strokes, pulmonary edema or digestive hemorrhage. Working there can also cause respiratory and muscular problems.

In the town of Cachoeira, I met Sergio da Conceição Rocha, a quiet man who offered to be my guide. Like many others, working in the cane fields had been his first option. He started cutting cane at 18, but asked to be transferred to another job a year later. “I couldn’t take it any longer,” he told me. For 11 years after that, he took care of preparing the land, planting and fumigation, all of which involved their own high health risks.

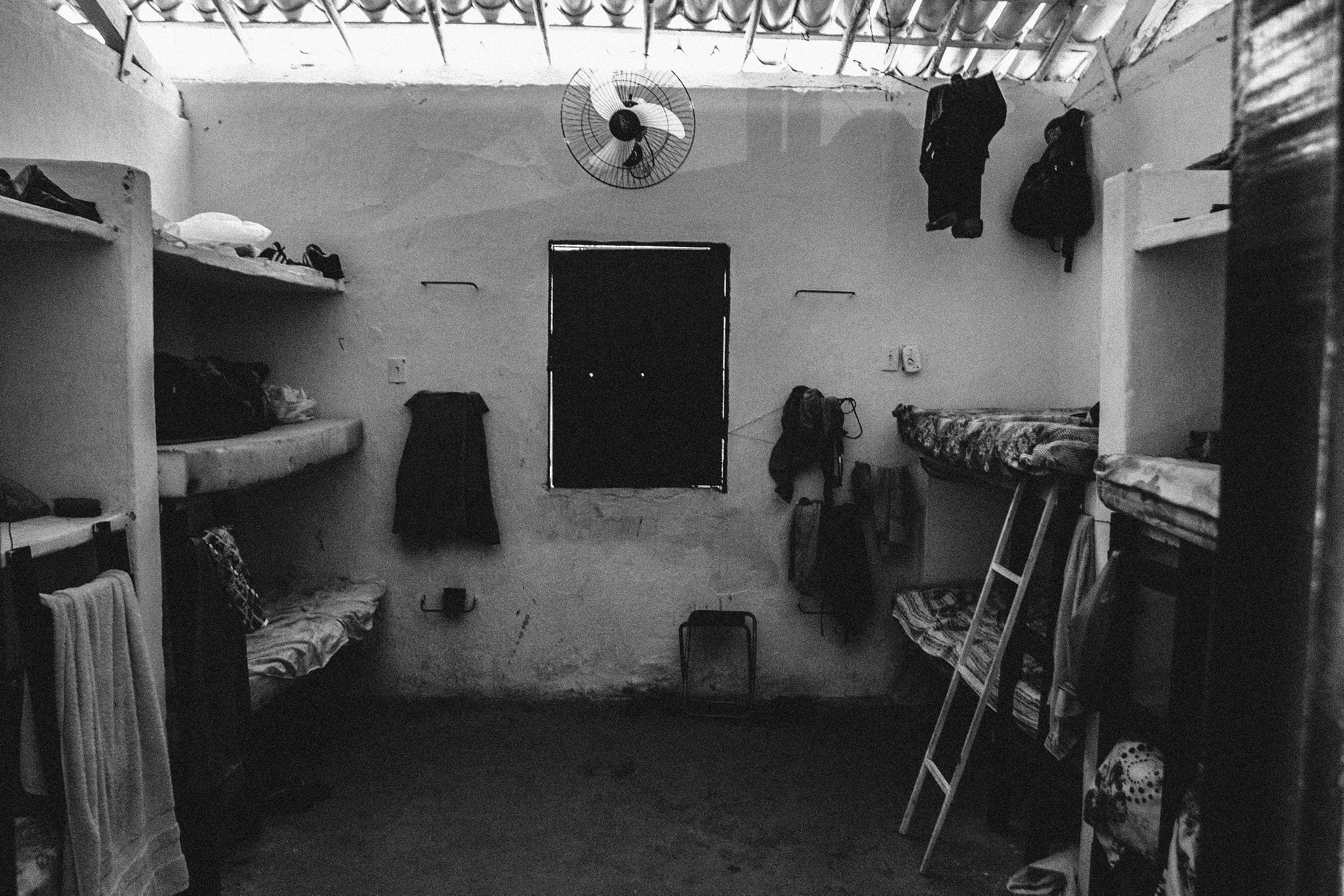

After getting married, he was pushed to look for another job by the low wages and health risks. Today, at 37, he works for himself as a construction worker. He took me to the lodgings where sugar cane workers live and we met his old coworkers. As we walked around, he told me he was surprised to see the living installations had improved. “But one thing doesn’t change,” another worker interrupted him: “the difficulty of living like this for a long time.”