Falconry is making a comeback in the United States and elsewhere. Inside the strange regulatory world of modern government-sanctioned bird-hunting.

Anatoly Tokar caught his first sparrowhawk on instinct. Spurred on by the birdsongs and tales from the bird markets of his hometown, Kiev, Ukraine, he had started trapping songbirds in the wild by age 12. When one day he saw a hawk swoop down on a calling bird he’d captured, he just decided to try slinging a bow net over it as well. As Tokar says, “that’s probably how [the invention of falconry] happened thousands of years ago: you just try it.” With no community of falconers in the Ukraine, he trained himself as a falconer using only scarce lore and a 10-page, 19th century Russian language manual on catching quail with sparrowhawks. When, later in life, Tokar became a herpetologist and moved to upstate New York, he expected to be similarly isolated in his raptorial concerns.

As it turns out, the United States government is also interested in falconry. It cares enough that in 2008 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a 64-page report with eight potential rules limiting the capture of wild peregrine falcon nestlings by falconers. (Of the alternatives, they settled on this: 116 nestling and first-years may be taken west of 100° West, including Alaska, and 36 first-years east of 100° West.) Among several hundred other pages of falconry-related legislation and regulation, federal and state authorities have required that hybridized raptors, cross-breeds of peregrines, sakers, gyrs, and others mixing and matching their best qualities to create super-birds, be flown with two radio transmitters affixed to their bodies, and that state-accredited Master falconers keep no more than three golden eagles. And various state agencies, like the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, care enough to monitor all of this, requiring that all falconers submit a yearly report on all the birds in their possession; all the birds bought, captured, released, lost, or killed (within ten days of an incident); and all their dispositions and falconry uses.

Falconry is an ancient sport, practiced by humans for between 3,000 and 12,000 years (depending on your choice of lore and evidence). In its medieval heyday, even English peasants kept sparrowhawks and goshawks; entire volumes, like the Boke of St. Albans, were composed on the types of birds permitted to the various classes of English society. And though it’s often associated with medieval Europe or the Central Asian steppe, the craft has a fair history in America, where immigrants brought falconry into the frontier in the 1800’s as a useful supplement to hunting. With the passage of time, however, it got harder to hunt by falcon. The social distinctions and values associated with falconry declined and disintegrated, and by the end of the 19th century the art of hawking had become an obscurity in much of the West. It became such a relic that, in the early 1930’s T.H. White, the Once and Future King author, trained himself to hunt with a goshawk using a 1619 manual, Bert’s Treatise of Hawks and Hunting, in a fit of medieval, primal fancy.

Within the past fifty years, though, falconry in America has bounced back, growing in visibility and popularity. You may not know it, but we are living in what is some are calling a golden age of American falconry, given the number of falconers, respect for American birds in the international falconry world, and popular awareness of the sport. Golden age might seem a tad exaggerated, but when compared to much of living memory, it’s a vast improvement. This rebound is not a retreat into the mythologized and idealized Middle Ages. Rather, it’s a fusion of the old hunter-naturalist ethos of the falconers who preserved the sport with environmentalism and conservation movements attempting to save the birds.

It started with the near-extinction of the peregrine falcon, long a favorite of falconers. Beginning in the 1950s, the increasing prevalence of DDT pesticides led directly to the thinning of peregrine eggshells, drastically decreasing the number of chicks successfully bred in the wild. By the 1970s, only 39 mating pairs of peregrines remained in the western U.S., according to some estimates. And many of those remaining were not exactly hearty and hale, much less ready and willing.

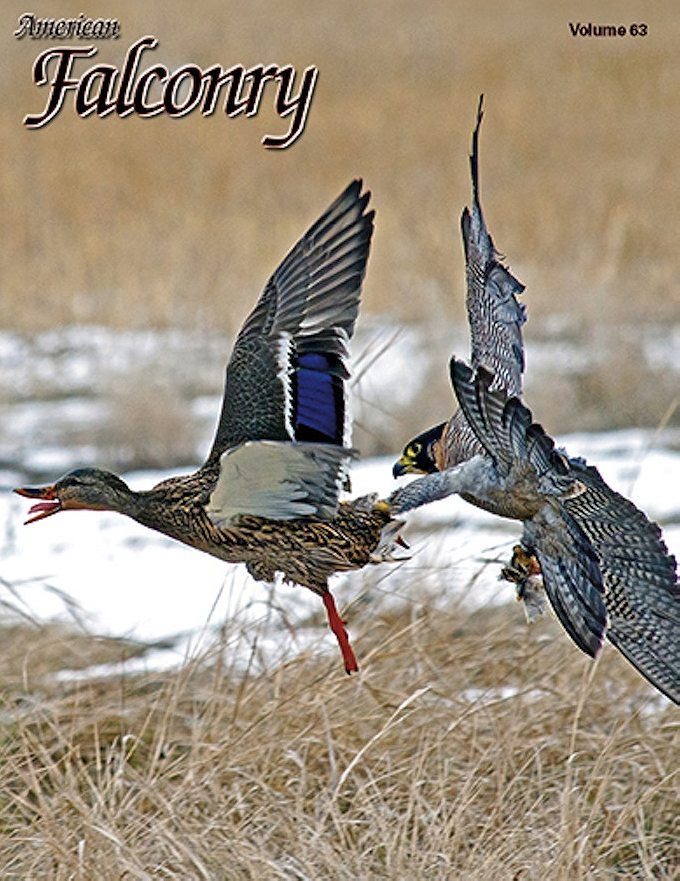

The decline of the bird was of little note to most of the public. The modern costs and commitments of falconry, far outweighing the poundage of meat brought in, meant that the birds were far less intertwined with American life than they had been in the frontier days. Between housing, food, transit, swivels, gloves, bells, leashes, jesses, lures, leatherworking tools, perches, hoods, telemetry equipment, and training, the modern falconer can expect to pay up to $9,000 in his/her first year of bird ownership, per bird. That’s to say nothing of the one hour daily training and nine hours weekly hunting per bird, minimum, as recommended by the trade magazine American Falconry.

Those who had stuck by the craft into the 1960s were a small band motivated less by hunting for sustenance and flight tricks than by a deep love of the birds and their behavior. Tokar and his mentors like Ed Pitcher and Steve Chindgren don’t like the idea of training birds to do aerial gymnastics, or going out with the goal of catching a set amount of game. Instead, for them their love of falcons is all about observing their behavior, pampering them as little as possible, and watching them grow into their instincts. Chasing this connection with nature, they sink their lives into the birds: Lars Sego, a breeder in New Mexico, got his first bird around age 8, after practicing with a chicken he’d perched on his arm in a jess and hood, watching it jump onto bugs. Tokar himself is currently flying seven falcons and six hawks.

At the same time as these naturalist bird fanciers were getting worried about the decline of the peregrine, environmentalists had started to float the idea of conducting large-scale wildlife conservation programs. Eventually, the two parties collided and the apostles of falconry joined forces with conservationist Tom Cade of Cornell University to found the Peregrine Fund. Over thirty years of collaboration between the falconers and biologists, using the keepers’ captive stock and scientists’ know-how to breed back wild mating pairs, the Fund became one of the most wildly successful conservation projects ever. By the time the campaign succeeded in 1999 in removing the Peregrine from the Endangered Species List (which the Fund predated), the falconer-scientist alliance had pioneered tactics to be used in rehabilitating other bird populations, raised the profile of the once obscure falconers, and brought a number of environmentalists and biologists into the sport, increasing the number of falconers in the nation and the visibility and ambition of the craft.

The growth of falconry, combined with concern over species like the peregrine and golden and bald eagles, led inevitably to governmental regulation. The first federal legislation appeared in 1972, when a treaty with Mexico set federal law on raptor possession and use. By 1976, the government had worked out comprehensive legislation for the sport of falconry. Chiefly, this was about issuing licenses to monitor and control the levels of falconry and wild bird capture in the world. As a result, we know that there are approximately 5,000 active falconry licenses in America (563 in California, although the rough and woodsy Wyoming, Idaho, Alaska, New Mexico, and South Dakota have the most falconers per capita). Bob Collins, the archivist at the Peregrine Fund, suspects that only 3,000 of these licensees keep and fly birds, but even then that represents a doubling of the number of falconers since tracking began.

In creating a licensing scheme, the 49 states allowing falconry (Hawaii, D.C. and the territories do not permit the practice) had to develop competency tests, study materials, and gradations and regulations on the number and type of falcons one could keep with varied levels of experience. Essentially, they were tasked with building the infrastructure of a medieval craft guild.

Here’s what they came up with. According to federal regulation, one may choose to become an Apprentice falconer at age 12 (with parental permission) and may possess one bird so long as it is not a bald, white-tailed, golden, or Steller’s sea eagle; an American swallow-tailed kite; a Swainson’s or ferruginous hawk, a prairie or peregrine falcon; a northern harrier; or a flammulated, burrowing, or short-eared owl. The Apprentice must study for at least two years under a General or Master Falconer, whose permit he/she must receive to advance to the next level. One can become a General Falconer by age 13. The Generals are allowed to keep up to three birds, so long as they are not eagles, and must study for five years under the guidance of a Master. When the Master consents and the state permits, the General becomes a newly minted Master Falconer with the ability to keep up to five wild birds, three golden eagles, and an unlimited number of captive-bred hawks, falcons, or owls. All may take two birds from the wild annually.

Many of these restrictions are entirely modern. Having a Master level allows the government to prevent anyone without a high level of training and respect for birds from launching an abatement venture, in which falcons are used to scare birds off of airfields and prevent collisions between jet engines and seagulls. (Many abatement services are based in California, accounting for the prevalence of falconry licenses in that state, although their technicians do not always adhere to the lofty and sentimental ethos of modern falconers. They train their birds, for instance, to just go out and chase seagulls in a set, artificial field rather than helping them to realize their natural hunting instincts.) And limiting the types of birds one can take at separate levels helps to protect populations. Meanwhile the impetus this creates to report one’s aviary yearly helps the government ensure that no hybrids—breeders in America have developed a specialty in popular, fast saker/peregrine/gyrfalcon mixes—escape into the wild.

The root vocabulary of these modern regulations—bird take, Master Falconer, jesses and hoods—are remnants of archaic falconry. Governmental and private conservation and protection of falcons have been exceptionally successful. They’ve saved falconers, their craft, and their charges. And they’ve given new life and a new audience to the art, not just in the U.S. but in the UK as well. Most days, at least a handful of families from all around the countryside trek out to the Millet’s Farm Falconry Center, one of those quiet bastions of desperately maintained English rural tradition half an hour southwest of Oxford, to watch trainers trot out their birds and put on flying shows. Owls, hawks, and the ever-popular hulking vultures flit about the yard, chasing scraps of meat and showing how high they can go. And the falconers tell the rapt audience about conservation, heritage, and the natural value and beauty of the birds. But no matter the success of this and many similar falconry centers in America, modern falconry still feels a bit like a burlesque: a clash of the mythic and the modern, all under the hawkish regulatory eye of the federal government.