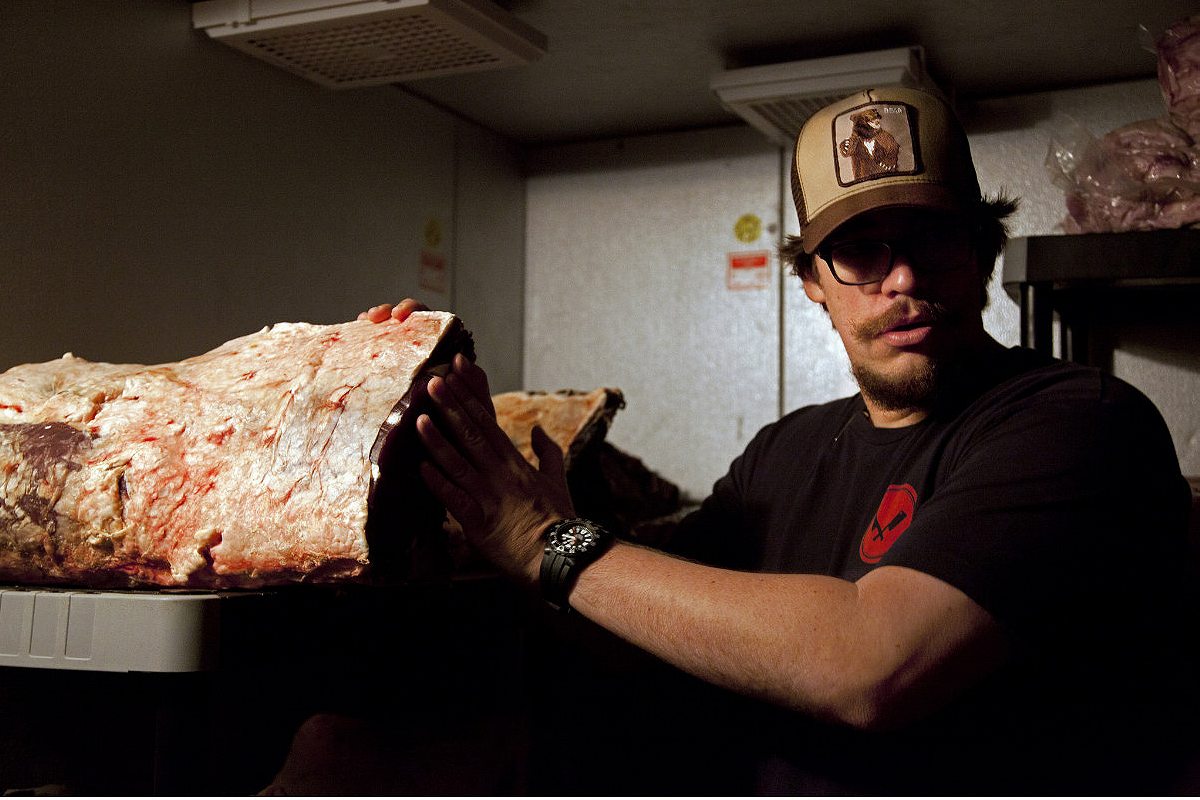

In the back room of a butcher shop in Lima, Renzo Garibaldi is doing things with meat that no one has ever seen or thought to do.

The most interesting things being done with meat in South America at this very moment aren’t happening in the beef temples of Buenos Aires. They’re not happening in the open pit asados of Mendoza or Salta or the parrillas of Uruguay or the churrascarías of Brazil. They’re happening in Peru, the country with the lowest meat-eating index in all of Latin America.

Specifically, they’re happening around a large table in a back room at Osso, a butcher shop on the outskirts of Lima, inland across the traffic clogged artery of Avenida Javier Prado and beyond the dusty brown hills in the residential district of La Molina. This is where butcher Renzo Garibaldi is doing things with meat that no one here or anywhere has ever seen or thought to do.

Six foot two with a shaggy goatee and a Paul Bunyan build, Garibaldi, the son of textile entrepreneurs, took a job at Sushi Samba while studying international business in Miami. When he moved back to Lima he enrolled in a culinary school and later took a job slicing fish at Costanera 700. He moved to the US to be a part of Gastón Acurio’s team at La Mar in San Francisco and while there, he took a class with master butcher Ryan Farr of 4505 Meats. Everything changed. He fell in love with meat. He became fascinated with the art of the cut and the anatomy of cows and pigs. He soon quit La Mar, landed an apprenticeship with Farr and immersed himself with some of the world’s best butchers. He moved to La Granja Baradieu in Gascogne, France for a stint with the Chapolard brothers to master charcuterie and pig butchery, then to New York to work with Joshua Applestone at Fleisher’s. Wanting to bring a touch of that meat culture home, he and his wife moved back to Lima and opened Osso in the upscale suburb in mid-2013.

The primary operations here are the same as any other butcher shop. Glass cases are filled with different cuts of meat. There is an entire rack of house-made chorizos, with uniquely Peruvian flavors like anticuchero or rocoto pepper marmalade and ají limo. There are smoked porterhouses, pastrami, Duroc pork belly bacon, and pre-made burgers, plus a blackboard list of offerings for barrel ovens and caja chinas, like pancetta and pork shoulder. There’s also Kurobuta fat, Peruvian craft beers, bags of pork rinds, and even Kobe beef-infused treats for dogs.

Garibaldi and his team can often be seen behind the glass counter breaking down entire carcasses. Behind them another temperature controlled case stores the finer cuts, like the NY Strips of marbled wagyu from Snake River Farms, which he imports from Idaho, plus bone in rib-eyes and cowboy steaks. Then there is the meat locker full of large carcasses are hung from the ceiling, all in different stages of decomposition.

But it’s what’s happening in the back of Osso that has been capturing everyone’s attention. This is where for the past year Garibaldi has been holding clandestine dinners around a single large wooden table for no more than eight guests at a time.

As I enter the back room with a few friends, the table is already set with trays of charcuterie: duck rillete, roast beef, and salami. Behind the table is a wood-fired grill. It’s as raw and crude of a space for a tasting menu as I have ever seen. There’s not even silverware. Everything is eaten with your hands here.

Soon out comes a bowl of lardo, a soft mound of cured pork fat, which we scoop on to crackers. Next come chorizos, one of ají amarillo with huacatay, classic Peruvian flavors, and another made with maple syrup. Then sliders made with 30-day-aged beef and topped with gruyere. Ten minutes later Garibaldi wheels out a stand with a wooden bowl with a pile of chopped beef. He cracks open an egg and starts mixing this crude tartar tableside with onion, chives, and salt. An assistant of his scoops out servings into our hands right from the bowl.

All of this makes for a rousing start, but the real magic occurs when the meal moves to the grill. Cooking over live fire is irregular. Controlling the heat with the consistency he does is something few can do. Cut after perfectly cooked cut comes to us right off of a cutting board. The Wagyu short rib, seasoned with soy sauce and panela, is probably the best short rib I’ve ever tasted—the prefect combination of sugar, salt, fat, and smoke.

He follows with a porterhouse, an axe-handle rib eye, and a string of other imposing cuts that he’s carefully aged at Osso. This is where Garibaldi is moving the traditional grill master role into unchartered territory. They start at 30 days, then increase to 45 and 60. You can taste the collagen breaking down a little bit more with each cut, resulting in more nuanced flavors. Each is muskier and funkier than the last. He finishes some by holding them directly over the flames. Others he sits right in the charcoal and covers in ash. He moves on to a steak aged 120 days, and then, for the grand finale, a 160-day-old piece of Wagyu. Over the course of nearly six months of aging, natural enzymes in the protein break down and the carbohydrates are converted into sugar, so the flavors are richer and more concentrated. The sizzling beef smells like buttered popcorn. Every bite tastes of pure umami.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Osso was just supposed to be a butcher shop. He liked the idea of resurrecting serious butchery—a once dying art that just a decade ago was left for dead in most corners of the culinary world—in Peru in the way it was being done in Brooklyn and San Francisco. He’d follow the path of this emerging movement of sustainable, hormone-free meats and find ways to use every part of the animal. There would be six of them working, including his wife, Andrea, who handles all of the administration. They had the back room built and added the grill so he could just invite friends over to hang out. “I thought the meat I had that I didn’t sell beyond 21 days we would eat and maybe have a few beers.”

He casually mentioned he would do this to a few friends. Two of them were Gastón Acurio, the iconic Peruvian chef, and Mitsuharu Tsumara, of Nikkei restaurant Maido, and they took him seriously. Suddenly, three weeks after opening the shop, they began getting calls for reservations. They said they must have the wrong number. The calls kept coming. They would say, “But Gastón and Micha said you have this amazing place in back, no?” Finally they said they would put something together.

“We didn’t understand exactly what was happening and we weren’t prepared, but when someone like Gastón pushes you in this direction you have the responsibility to try,” he said.

They didn’t have silverware, so they decided diners would just eat with their hands. They didn’t have glasses so they borrowed some from his parent’s house. There was no intention of opening a restaurant.

Now there is a staff of 30 and they’ve done 230 dinners over the past year. Sometimes two per day. Curious eaters make the pilgrimage from all over of the world. A cast of Chilean soap opera stars flew here for one day just to eat in the back room. A group from Spain came after they overheard a waiter from El Cellar de Can Roca talking about it while they were eating there. The Peruvian cardinal even came. They are sold out at least two months in advance and that list keeps growing longer every day.

This brings us to Osso phase two, where things get even more interesting. Next door to the butcher shop, where the café Eggo used to stand, the butcher shop is being extended into a full-blown restaurant. The one table in the back of the butcher shop is still the heart of the operation, though they’ll now have 38 seats and a kitchen designed for zero waste, so everything that he butchers will be used.

They added the restaurant so they can accept walk-ins and serve a standard menu with some plates coming off the tasting menu, like the tartar or an asado de tira, or short rib, that has been smoked for four hours, cooked sous vide for 30 hours, and then finished by holding it directly over the flame.

He won’t be using much charcoal, mostly eucalyptus, which has been growing in abundance in Peru since Franciscan friars planted it in the Andes in the 19th century. There’s also sustainably managed applewood, orange wood, and pasapailo, a native wood his supplier turned him on to.

Garibalidi takes Osso’s eco footprint seriously, but he also takes pleasure in less earnest aspects of the meat business. His favorite part of the restaurant is a picture of a sausage in the men’s bathroom. “So you’re peeing and you look up on the wall and it says ‘nice sausage.’”

A few days after opening the new restaurant, I meet up with Garibaldi. We drink beers and talk about the future of Osso. Another degustation is about to happen over on the other side in the back room and we join the guests waiting for the rest of their party to arrive. It’s BYOB in the back so one brought a bottle of wine and Garibaldi tells someone on the staff to put it in a fridge at 15 degrees Celsius. Another brings a cooler filled with bottles of beer and champagne.

Garibaldi wants it to be food you eat with your hands.

Garibaldi starts talking to them about golf, which he recently picked up. He says he goes to the course still wearing his flannel shirts and that the other golfers are probably afraid of him. He doesn’t give a shit. “I’m like a lumberjack golfer,” he says.

He has picked up other habits, too, and his natural curiosity pushes him to extremes. He mostly drank beer when the restaurant opened, but he has also gotten into wine lately because all of the guests keep bringing different bottles and insist he has a glass. “I’ve been getting into Super Tuscans. One day someone brought in an 86 Chateau Palmer.”

He’s careful not to make Osso a fine dining experience though. Even if someone brings in a $2,000 bottle of wine he wants it to still be food you eat with your hands.

The heart of the dining experience, the cuts of hyper-aged meats, is another part of the happy-accident narrative that defines Osso and Garibaldi. He didn’t learn anything about this from the Chapolard brothers or Applestone or other experimental butchers. It all happened here.

“After we opened we realized I was bad at handling inventories,” he tells me. “I thought I was going to sell 21-day-old meat and that was it.”

At times he over bought, so instead of throwing it out he just kept it in the coolers to see what happened. “People started to get excited about things that were 50 days old. I didn’t really think about the numbers then.”

Now he is thinking about the numbers. The longer this lower quality national meat isn’t eaten, the more the connective tissue is broken down and becomes something else.

“With meat that has been aged for 21 to 60 days there is a change, but it won’t blow you away,” he tells me. “At 150 days old it’s another story. At 200 days old it’s like the difference between a boxed wine and a 30-year-old Bordeaux. It’s so complex, so elegant to analyze.”

In the back other cuts are still waiting their right time. As is the cattle business here as a whole.

Beef has never been Peru’s strong point. There’s not a culture of eating prime cuts and most of the higher quality beef is imported, therefore expensive. Despite the country’s biodiversity, the barren coast and arid Andes lack the grasslands and the water to support large scale grazing. Therefore national cattle are of rather low quality compared with Peru’s more carnivorous neighbors like Chile and Argentina. Yet, within the various microclimates artisanal ranchers have potential to carve out a niche.

“Peru needs another one or two more years and the meat industry will explode,” he says. “We’ll start having people investing in long term cattle projects.”

Things are already happening. Most of them have some sort of Osso connection. In the jungle, there’s zebu, the hump-backed tropical cow from Southeast Asia that some ranchers are trying to develop. They need some help from the government to be able to move their product to the coast, but it should happen eventually. In another part of the jungle another group is breeding a cattle that eats the upper part of sugarcane plants, which are usually just tossed out. “The fat has a lot of character. A lot of flavor,” he tells me. “It’s intense. Aggressive. Very cool. Salty.”

They need about another year and a half before he’ll be able to get the meat regularly.

Culinary innovation has existed for as long as people have walked the Andes.

What’s so encouraging about Garibaldi’s future, and the country’s potential with meat in general, is how much Peruvians have already done with meat for so long with so little. No scrap has gone to waste. Slaves working on coastal plantations took the leftover bits from a butchered cow, such as the heart, and seasoned them, skewered them and continually marinated them so they taste as tender a filet mignon. Anticuchos are now a favorite Peruvian snack. Cow’s foot? Toss it in a soup until it’s rich and gelatinous. Guinea pig? Roast it, grill it, fry it, or turn it into a terrine. Throw out chicken blood? Fuck no. Season it and cook it and you’ll have sangrecita.

The country’s biodiversity seems to always be the topic of conversation here when it comes to food. You have tree resins that can be turned into gels and more naturally occurring fruits and freshwater fish than anywhere else on earth, but there’s a spirit of culinary innovation here too. It has existed for as long as humans have walked the Andes, from the Incas finding ways to freeze dry potatoes to expand their empire to Japanese chefs in the 70s tweaking how long citric acid should be doused over raw fish for ceviche. Osso isn’t just a butcher shop or a carnivore’s paradise. It’s another part of that story.

Osso Carnicería & Salumería

Calle Tahiti 175

La Molina, Lima, Peru

For Reservations: (51) 1368-1046