In a nondescript chapel in a blue collar neighborhood rests the largest collection of relics outside the Vatican.

Just north of the Alleghany River from downtown Pittsburgh lies the unassuming working-class neighborhood of Troy Hill. Since its founding in 1833 by German immigrant farmers, the tiny, sloping cluster of drab multi-story homes has been a solidly low-key, blue collar, and off the radar affair. But at the center of the neighborhood, recessed on the little side road of Harper Street, sits what may be one of the most deceptively remarkable chapels in America, if not the world.

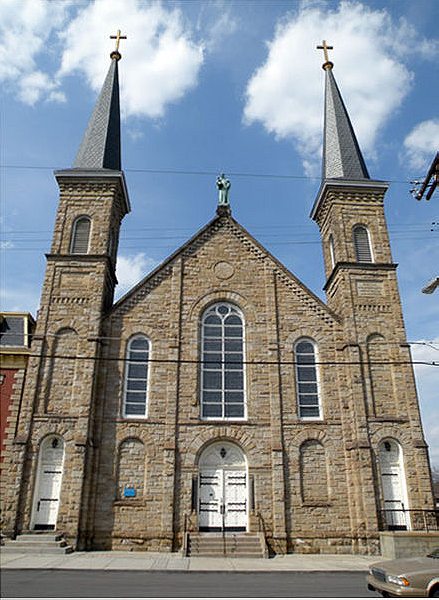

From the outside, St. Anthony’s Chapel doesn’t look like much—just two towers, grey-brown rough hewn stone, and a steeple rooftop like you’d find anywhere else in America. Inside, though, the church is sumptuousness incarnate—all life sized statues of Jesus’s procession to the crucifixion, rich carvings of golden and mahogany hues, and near-glowing murals. It’s not the décor that makes the place stand out, however. It’s the collection of relics, about 5,000 in total, the largest outside of the Vatican, that lie in reliquaries throughout.

The relics housed in St. Anthony’s are no trifling things, either. There’re no pieces of cloth that touched a piece of cloth that touched a saint or suspicious duplicates of saints’ pinky bones found elsewhere in the world. Almost all of the relics are first or second class, meaning they include saints’ body parts and possessions. The more popular relics include: 22 splinters of the True Cross; threads from the Virgin Mary’s veil; a cloak of St. Joseph; and bone fragments of all 12 apostles; the entire skeleton of St. Demetrius; the skulls of several older and newer (and thus lesser known) saints; and a molar once belonging to St. Anthony, the very tooth missing from his skull in Padua. All of the reliquaries are marked on the back with letters of ecclesiastic authenticity, verified long after the heyday of falsified relics.

It is, in other words, as close to the real deal as you’re going to get. Yet almost no one—not American Catholics and not even residents of Troy Hill—know much about the chapel and its reliquary, or how such a massive collection wound up in a little German immigrant neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

The story of the relics starts with the chapel’s founder, Father Suitbert Mollinger of Troy Hill’s Most Holy Name of Jesus Parish. Born into a wealthy family in Mechelen, Belgium, in 1828, Mollinger studied medicine in Italy and theology in Ghent before just sort of drifting to Troy Hill as a missionary in 1868. Within his lifetime, Mollinger gained a following throughout the northeast not as a relic hoarder, but as a miraculous medicine man, founding a small medical supply company and marketing a variety of kidney pills. He also took on a number of poor patients from all around the region, so many that Troy Hill was at one point known as the “Mecca of Invalids” and the trolley running up towards the neighborhood was nicknamed Mollinger’s Ambulance.

Just as he was gaining a near-cultic following, says Carole Brueckner, a lifelong parish member and the Chapel Committee Chairperson and Docent for the past several years, “he also had agents who were looking for these relics… back in Europe.” The 1870s were a great time of strife for Catholics. Between Giuseppe Garibaldi’s libertine unification of Italy and Otto von Bismarck’s Realpolitik Kulturkampf in Germany, churches left and right were being stripped for parts by the emergent states. This included, according to Brueckner, smashing reliquaries not to resell the relics but to use the gold and gems in their cases. For whatever reason, relics were something Mollinger cherished dearly, Brueckner says. “With all of this going on in Europe, he was able to acquire them and bring them to the United States and save them.” Just to house his growing collection, he built the Chapel in 1880 with his own family wealth, enlarging it in 1892.

Then, two days after a feast and pilgrimage of 12,000 faithful to celebrate the chapel’s growth, Mollinger died (a passing that earned a mention in the New York Times). His estate sold the chapel for $30,000 ($750,000 in modern dollars) to his congregation, and his kidney pills continued to sell at least until the 1920s, but the devotion heaped upon his chapel died with him.

Devotees to St. Anthony continued to make the journey, Brueckner says, but “the drawing point was Father Mollinger… People would flock just to see him in hopes that he could help them spiritually or even physically.” After his passing, most no longer had a reason to visit the chapel and the congregation struggled to raise the private funds or keep interest alive in the relics. By the 1970s the chapel had fallen into such disrepair that the diocese considered tearing it down, but relented when a small cadre of devotees from the parish stepped forward to raise funds and form a committee to renew and maintain it.

After restorations were completed between 1972 and 1978, one might have expected to see a rebirth at the chapel—a widespread promotion of its heritage and holdings to the world at large in hopes of drumming up support in the future. But that never happened. Sure, a few further projects made the relics more accessible, like an effort by two nuns to catalogue and verify every relic and publish their works. And knowledge of the chapel spread far enough that Brueckner says people continue to bring them newer relics—perhaps 200 of them—because the felt these items belonged in a place like the chapel. But beyond that there’s been no tourism rush and no mass recognition. “Within the community, not everybody even knows about it,” Brueckner says.

Part of that probably has to do with the very tempered American Catholic approach to relics. The spiritual basis for relic veneration (Brueckner would like to note that, although this is a common term, it is misleading, as it’s actually veneration of the saint through his or her relic) goes back to Acts 19:12. This biblical passage shows early Christians using the cloth of the apostle Paul in healing rituals. But the use of relics really kicked into gear in 787 when the Second Council of Nicaea declared every church ought to have a relic (although this conviction lapsed after Vatican II in the late 1960s).

In the Internet era people can buy their own fragments of papal bones for $350 a pop

But Americans never had the same fervor for relics as their European Catholic counterparts, given the original minority status of Catholicism in America and the lack of major shrines and indigenous saints early on, says Thomas Crughwell, author of 2014’s St. Peter’s Bones and the earlier Saints Preserved. “In general, the American Catholic approach to relics has been fairly low key,” Crughwell says. “Yes, there have been and still are pilgrimages to various shrines that have relics in the U.S., but they tend to be small scale. In my research, I’ve never found any relic in the U.S. held in particular reverence by American Catholics.” (It can’t help, either, that in the Internet era people can find and buy their own fragments of papal bones for $350 a pop, somewhat devaluing the mysticism of a reliquary.)

But even without holy significance, 5,000 beautifully displayed relics is still a trove worthy of sheer secular spectacle. So the lack of attention and awareness regarding St. Anthony’s probably has to do more with the very mellow approach of those who manage it. “We do advertise, but it’s not on the front page or anything,” Brueckner says. She details the full extent of what they’ve done to promote the Chapel: They put up a website to list all their special liturgies and weekly devotions to St. Anthony, got it listed in a catalogue of places to see in Pittsburgh, and put brochures at major events about ten years ago, and have kept that up.

It’s not that the chapel caretakers are lazy or apathetic. Quite the opposite, actually: They’re fervent and true believers, and as such they believe there’s no need to advertise because the people who need to find the relics will come. “People do come and I believe that it’s someone St. Anthony wants to be there,” Brueckner says. “When people enter the chapel… many of them feel a presence—something different. Something happens.”

She felt the spiritual power of the chapel herself many years ago when undergoing a personal challenge, hence her own deep faith in the pull and provisions of the chapel for those who need it. So this is how St. Anthony’s will remain: a thoroughly sanctified gem hidden away in a little splotch of the rust belt. Some will happen upon it, and some may even feel drawn to it. But as far as the community behind the chapel is concerned, it is simply there, and famous or not that is enough.

[Header image: Pittsburgh by Sakeeb Sabakka, used under CC BY 2.0]