A Nigerian photographer investigates the meaning of hair by visiting barber shops across West Africa.

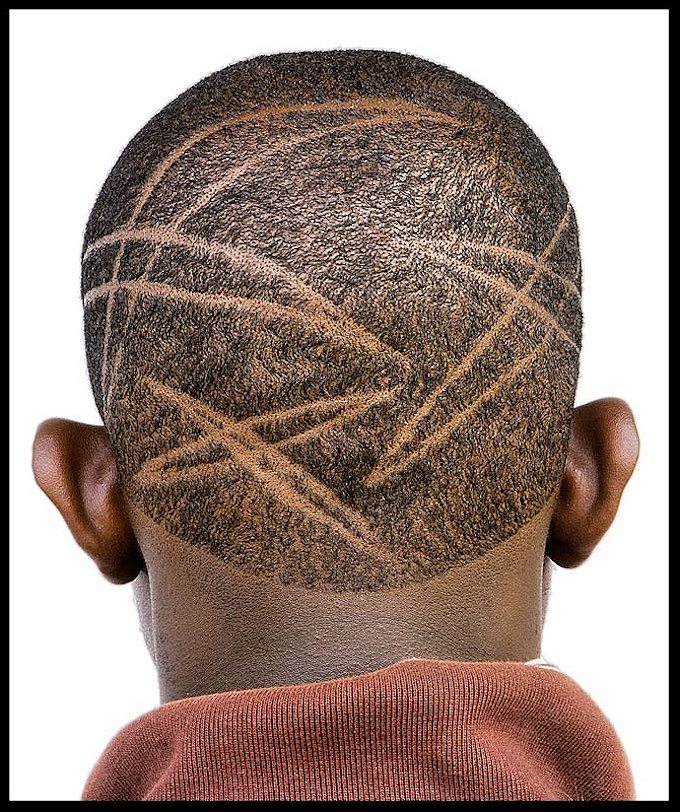

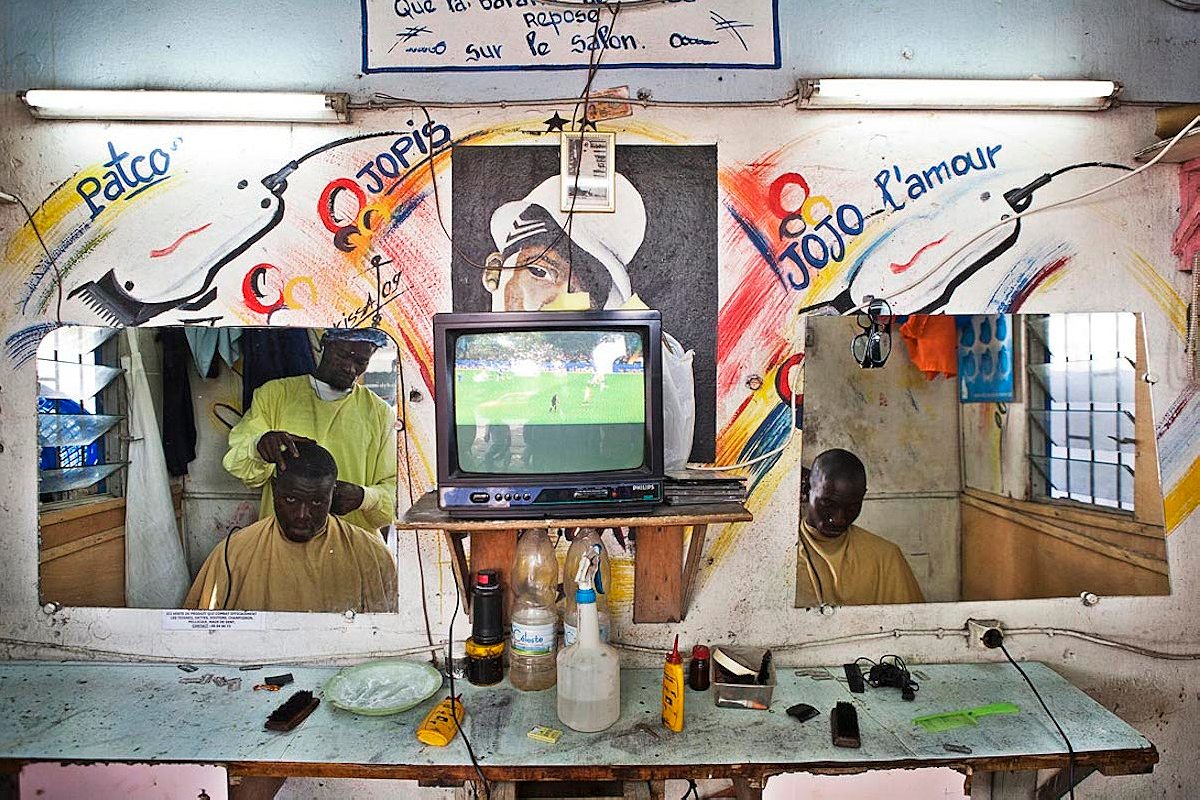

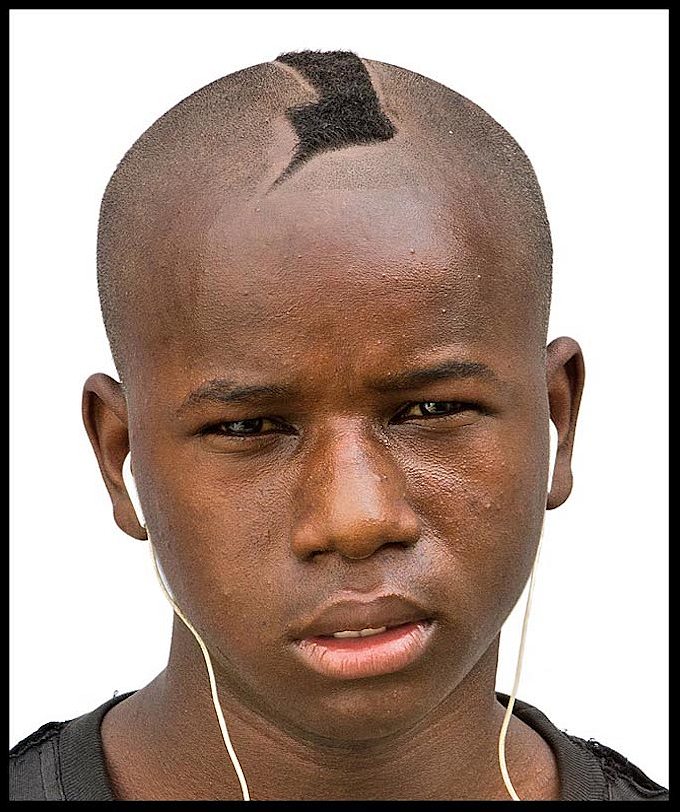

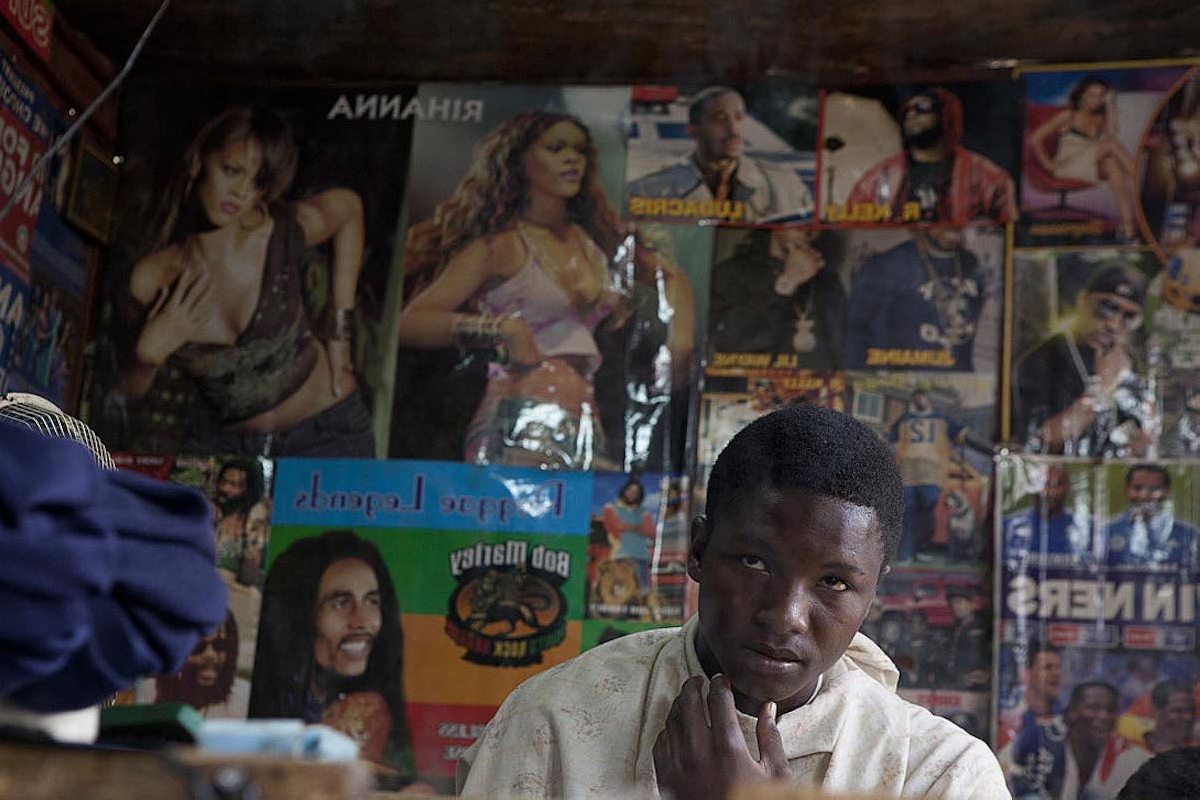

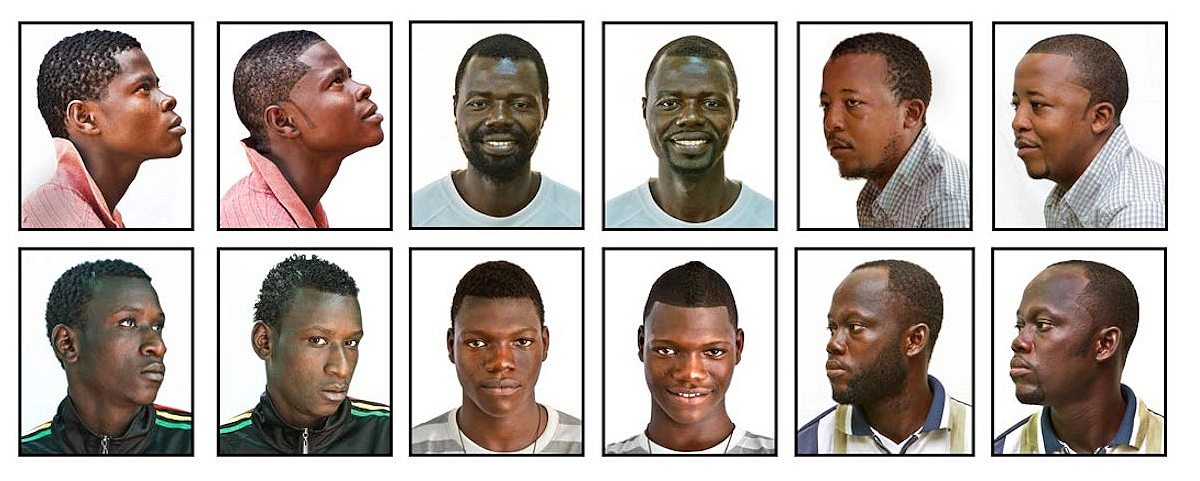

Andrew Esiebo hasn’t cut his hair since 2012 – the year he started the project “Pride.” Traveling to the urban centers of seven West African countries, the Nigerian photographer visited barber shops, investigating the meaning of hair within the local male communities. The deeper he delved into the subject, the more layers he found, as political, cultural and societal issues merged in these lively yet intimate spaces. And though it made it impossible for him to cut his hair, it gave way to a rich and nuanced portrait of modern Africa. “Pride,” a body of work of more than 100 photos, is broken into four sections: urban aesthetics, barbers, hairstyles and nuances. He spoke to Roads & Kingdoms from Lagos.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did you get started in documentary photography?

Andrew Esiebo: It was organic. Maybe it’s a reflection of what I’m interested in, but for me the key thing was to tell stories. There are a bunch of great photographers in Nigeria. The only difference is that not many of them do documentary work like me. Not many of them tackle the socially engaged issues I like to focus on. But overall, storytelling has been one of the things I enjoy doing the most. I want to be free. I don’t want to be confined to any kind of artistic or photographic practice. I have done editorial, worked on personal projects, worked with institutions, tried stuff on a conceptual level, collaborated with friends and colleagues on all kinds of photographic assignments, worked for NGOs, universities, I’ve done artistic residencies, workshops… But the key, again, is telling stories.

R&K: And when you started telling these stories, did you feel like your voice as a local photographer was unique? I mean, it used to be the case that Western photographers would often be the ones portraying the continent in the media…

Esiebo: Yes. This still happens today, but it’s changing. I’m a spontaneous person, so I respond to things that come to me. And I think the stories I tell are stories that resonate with me because of my cultural upbringing and my sensibility, so they are probably quite different from the ones told by someone coming from elsewhere. But it also depends on the market. Many of these Western guys who come to tell stories, they are influenced by what the media wants from them, so even if they have an interest in certain issues, if the media doesn’t, they sometimes get discouraged.

THE HISTORY OF OUR CONTINENT HAS BEEN TOLD BY NON-AFRICANS. NOW THAT WE HAVE THOSE TOOLS, I FEEL A RESPONSIBILITY TO FILL IN THAT GAP

R&K: How important is it for you to show your work outside of Nigeria?

Esiebo: For me, the location of where I show my work is not really important. What is important is to produce the work and tell those stories. Up until now, the history of our continent has been told by non-Africans. Now that we have those tools and those skills, I feel a responsibility to fill in that gap.

R&K: How does “Pride” help fill that gap?

Esiebo: The interesting thing about barber shops is that you find them in every nook and cranny of African cities. It’s what many of us see and ignore. But it’s a very important practice or feature of our city. It’s part of the urban aesthetics. Even the hairstyle is not just about fashion, it’s a form of expression. The barber shop itself plays a social role of bringing people from diverse walks of life together. It’s a local global space. If you look at the posters on the walls, some of them come from America, some show religious icons, some political icons… For example, you’ll find some shops that have posters of Osama Bin Laden and Gaddafi, celebrating them as their heroes. Barber shops have so many layers, and they have been ignored for so long. So I just thought looking at them was a good way to fill that gap.

R&K: How many countries did you go to?

Esiebo: I traveled to seven countries, but I focused on cities. One of the reasons for this was going back to the image you get from many African countries, always images that revolve around the rural communities, war, refugees, poverty… The urban space is a huge magnet for many people. Lagos for instance is where you have the biggest number of Nigerians living together. In Accra, in Abidjan, in Dakar, in Bamako, in Monrovia… I decided to create an alternative view of looking at that environment.

R&K: How did it work? Did you just walk around and go inside barber shops you found interesting?

Esiebo: I made some plans and relied on contacts, through institutions and through the help of colleagues and friends who are located in these countries. They pointed me to locations and I just went around by taxi, motorbike or just walking around, popping into barber shops. I would explain the purpose of the project and seek their collaboration, stay in their space, spend some time to study how they run their business.

R&K: Did they think it was strange?

Esiebo: They would not have been surprised if it was an American guy or Western guy asking to take photos. But for the first time, it was an African guy, so they were more suspicious. Some really understood the importance of the project and they said because I’m an African, they would go the extra mile to support me. I remember one guy telling me if I had been a white guy he wouldn’t have allowed me because he disliked white people and could not trust them. But for an African guy, he felt we were brothers and it was important for him to support me.

[CLIENTS] SAID THEIR HAIR WAS SOMETHING SPIRITUAL, SOMETHING PERSONAL, SO THEY CAN’T JUST GIVE THEIR HEAD TO ANY PERSON

R&K: You talk about a common pride that you found in all the barbers…

Esiebo: Yes. I think it comes from the fact that they transform people’s face. It makes them feel good. Every time I talked to barbers, they said they were proud of their job because it’s a craft that opened many doors for them. Through this craft they met many people, and they’ve been able to sustain their family. One guy I met said he was able to touch the head of the president. This common sense of pride was something that really interested me in the project.

R&K: Did you get your hair cut?

Esiebo: No, I have not been able to. It’s funny because normally I do cut my hair but since I began this project, I’ve been looking at my hair as more than hair. So I find it difficult to cut it now. I see it as something special. I started the project in 2012 and have not been able to cut my hair since. The feeling I have reminds me of what clients in the shops told me. They said their hair was something spiritual, something personal, so they can’t just give their head to any person. They need to find the right barber and the right person to touch their hair. Maybe I haven’t found that person yet. When I find that barber, I’m sure I’ll be ready to cut my hair.

R&K: How would you describe the atmosphere in the barber shops?

Esiebo: The barber shop is an open, public space. It’s lively in the sense that you meet all sorts of people. But it’s intimate in the sense that people get into conversations that they wouldn’t even have with their wives or their children.

R&K: Did you only photograph men?

Esiebo: Yes. First, what got me inspired was the encounter I had with this barber who said he was the barber of the president. Then, when I started the research about hair in Africa, I found out a lot of projects had been done around women. I just thought to add up to the body of work around hair, it would be nice to do something which is lacking. That’s why I focused on men. This also reinforced the idea of how hair can be used as a way of expressing masculinity.

“Pride” is on show at Tiwani Contemporary in London until February 8th, 2014. You can see more of Andrew Esiebo’s photographs here.