How Zola Mahobe changed South African soccer forever.

On December 5th of last year, South Africans bade farewell to Nelson Mandela. In general the new republic’s founding father was remembered as a principled, but pragmatic political leader. Some media coverage, however, reduced him to a one-dimensional figure, at odds with the larger South African struggle. That Mandela advocated armed struggle and formed alliances with communists was conveniently downplayed by all sorts of political causes and personalities whose politics Mandela would have opposed while he was alive, but who now claimed him as one of their own. Mandela was also favorably compared to his former wife Winnie Madikizela. His time in prison, presented as character-building, was contrasted with her increasing radicalism and criminal actions in the 1980s. Most black South Africans, however, were not scandalized by Mandela’s one-time celebration of violent struggle or his communist leanings, or by Winnie’s complicated, but flawed, legacy, which was formed in a more compromising, violent outside. As Stephen Smith rightly concluded in the London Review of Books recently: “If any one person can stand in for the country, it’s surely Winnie, half ‘mother of the nation’ and half township gangsta, deeply ambiguous, scarred and disfigured by the struggle.” Most South Africans get this full, complicated understanding of their recent history.

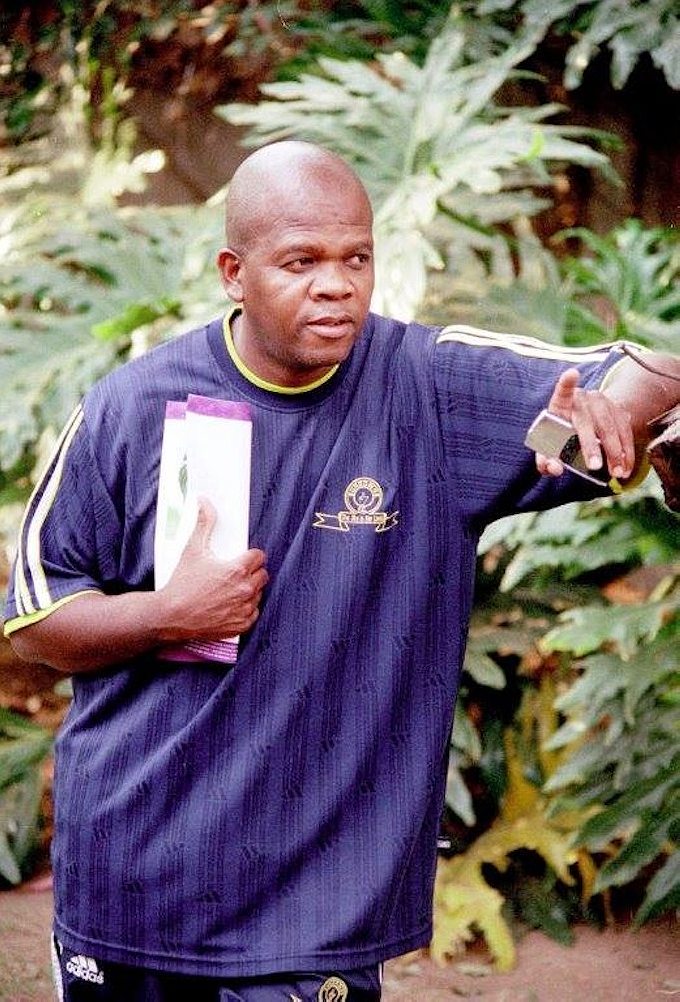

Zola Mahobe is another such complicated figure, part gangster, part hero. Mahobe, a legendary soccer club owner in South Africa during the 1980s, died nine days after Mandela. While his death quite rightly did not receive the same attention that Mandela’s did, his life was shaped by many of the same forces. For some, Mahobe was a symptom of what was wrong with South African professional soccer. Others viewed him (and still do) as a brilliant entrepreneur, a sort of Apartheid-era Robin Hood, and a visionary that would help reshape the dimensions of South African soccer.

But let me start from the beginning. I was in high school in Cape Town and a voracious consumer of soccer media when Mahobe first arrived on the soccer scene in 1985. Though white-dominated rugby ruled on Apartheid television as the state prioritized the sporting tastes of whites, the sole public channel also broadcasted highlights of the English First Division on the BBC’s famous “Match of the Day” program. Match of the Day played a significant part in forming black South Africans’ otherwise confusing devotion to English soccer. I would sit up late on school nights following the exploits of English teams in European competitions and of players with a South African connection, such as Richard Gough, Brian Stein and Gary Bailey. Through the BBC’s cameras, I became a lifelong Liverpool fan, but at the same time I was also developing an interest in local soccer.

HAVING BOUGHT THE COUNTRY’S TOP TALENT, MAHOBE SET ABOUT TURNING HIS PLAYERS INTO MEDIA STARS

Initially that was a challenge. South African soccer was a mess in the early 1980s. Banned by the game’s world governing body FIFA in 1976 (it took that long, yes), by the beginning of the 1980s there was no single national association and at least three local rival professional leagues in South Africa. There was the white-dominated NFL, which attracted aging British players much as the MLS does today, the black National Professional Soccer League (NPSL), and the Federation Professional League, which styled itself as “non-racial.” The first two often played friendlies against each other and eventually merged (the NPSL swallowed what was left of the NFL), while the third, consisting mostly of colored and Indian teams, remained “non-collaborationist.” In Cape Town there were big professional clubs, but Santos, Battswood and Glendale Athletic, the most popular clubs in the city, played in the Federation Professional League, and could not compete against the biggest of the NPSL clubs.

The NPSL had the best players. The league was on TV2 and TV3, the new TV channels the state created for “black languages” from 1982 onwards, and Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates, the two most popular clubs in the country played in it. Chiefs was founded by Kaizer Motaung, a plucky but unexceptionally talented midfielder who started his career at Pirates and later played for a few North American Soccer League clubs in the late 1960s. On his return to South Africa in 1970, Motaung shamelessly borrowed the logo as well as half of the name of his old club, Atlanta Chiefs (years later the name would be adopted by the Kaiser Chiefs, the indie rock band from Leeds, England) and half of Orlando Pirates’ players. By contrast, Orlando Pirates is the third oldest soccer club in South Africa—the oldest is the originally white Wits University—and their most famous fan was rumored to be Nelson Mandela, in prison on Robben Island through the 1970s and 1980s.

In the 1980s, the NPSL was becoming “multi-racial,” as it absorbed clubs from the old white league. Not surprisingly, when big sponsors (mostly white businessmen) started getting interested in the game, they went for the NPSL because of its large potential consumer and advertiser base. But the NPSL administrators were ineffective, beset by factionalism and doing little to improve playing facilities or the marketing of the game. Before long, the best clubs in the league (led by Chiefs and Pirates) led a palace coup against the NPSL to form the new, ambitious National Soccer League (NSL). Not surprisingly, other NPSL clubs and clubs from the old white league followed Chiefs and Pirates into the NSL. One of the first things the NSL did was announce they’d build a new “home” for South African soccer in Soweto. That eventually saw the construction of the 80,000-seat FNB Stadium in 1989; naming rights went to a local bank. That stadium would be razed in 2008 to build Soccer City, the 95,000-seater venue for Spain’s triumph in the 2010 World Cup final.

This instability and opportunism was consistent with the time. None of this soccer was recognized within FIFA’s international structures, and there was no national standard since there were four race-based amateur associations. But the soccer mergers also reflected the larger context for this period inside South Africa; that of “reform”—basically the Apartheid government, unable to exert total control and pressured from outside, allowed for laws to be relaxed. But this was also a criminal period for institutions in South Africa, including sports. Rugby and cricket, the most popular white sports, worked with the Apartheid state and business interests to break the international sports boycotts. A number of “rebel” cricket teams (Sri Lanka, West Indies, England and Australia) and rugby teams (the All Blacks) were enticed—with the use of cash inducements—to come and play against all-white national teams in South Africa.

Crucially, this was also the period when Zola Mahobe made a splash in local soccer.

Mahobe was from Soweto. After he finished school, he started with a small computer business, then a travel agency. He did pretty well, but he wasn’t outrageously rich. Mahobe was a consistent presence on the social scene since the mid-1970s, along with his pretty mistress Snowy Moshoeshoe, also from Soweto (he was married with children at the time). The two of them stood out. Mahobe was known as “Mr. Cool” and “Mr. Big Bucks” and cultivated this image with his flashy dress sense: afro, open neck shirts, rings and gold necklaces. Snowy, who was much younger (they met when she was finishing high school), came from modest means, but had a pronounced affection for shoes and imagined herself as a character in a Judith Krantz romance novel. It added to her mystique that she claimed to be related to the King of Lesotho.

In 1985 Mahobe bought the rights to a small soccer club, Mamelodi Sundowns, based in Mamelodi, a small dormitory township annexed to the capital Pretoria, an hour’s drive from central Johannesburg. The club was struggling in the NPSL and about to be relegated to the second division.

For Mahobe, owning a club was fulfilling a childhood dream. As he told a reporter for the Pretoria News in 2008: “My uncle, Harrison Selulu, owned a car and he was a Moroka Swallows fanatic. He used to take us with him to the games, but not to watch the match, only to watch over his car outside the stadium. We came up with a brilliant idea to follow him into the stadium and sneak out before the game ended. Fortunately it was never stolen.”

South African soccer’s center was Soweto, where the two biggest teams vied for supremacy. Kaizer Chiefs was known as the “Phefeni Boys” for a section of the township, while Pirates took its name from Orlando, Soweto’s oldest precinct. Cup finals were played at Orlando Stadium or in central Johannesburg. Mahobe himself started off as a Pirates supporter.

Mahobe decided to sign Sundowns up for the NSL in 1985, and promptly introduced a number of innovations, unheard of in South African soccer until then.

First, he began an aggressive policy of buying the best players from Chiefs and Pirates as well as other clubs around South Africa. Mahobe had them sign actual contracts (this was something new) and paid them massive salaries. Alex Shakaone, who worked as a media officer for Mahobe, remembered that professional players were being paid as little as “R300 or R200 a month”— the equivalent of between $110 and $160 at the time.

Having bought the country’s top talent, he set about turning his players into media stars. Before Mahobe, only players from Pirates and Chiefs were household names. Now Sundowns boasted the likes of Harold “Jazzy Queen” Legodi, Harris “TV4” Tshoeu, Sam “Eewie” Kambule and “Jan “Malombo” Lechaba and the Malawian Lovemore Chafunya.

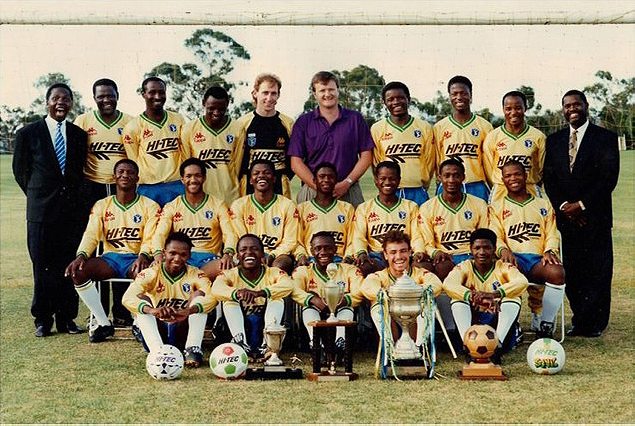

Mahobe outfitted the team in yellow jerseys and blue shorts and dubbed them “the Brazilians.”

Even Brazilians need a coach, and Mahobe decided Stanley “Screamer” Tshabalala, a former Orlando Pirates player, was the man for the job. Screamer had started his coaching career at Pirates in the late 1970s. Writing in an obituary in a Sunday paper after Mahobe passed away, Screamer remembered how Mahobe approached him: “He came looking for me specifically in Dobsonville (in Soweto) in 1984, when I was helping Blackpool. He gave me R50 000 (about US$40,000) to leave Blackpool—that was a lot of money back then.”

Mahobe’s appointment of Screamer was revolutionary. At the time white coaches more or less monopolized the top jobs in local professional soccer at the big clubs. Mahobe paid for Screamer to go on coaching clinics in Brazil and Italy.

Screamer introduced the team’s own playing style, known as “shoeshine and piano.” This didn’t amount to much in terms of tactics, but was about playing with style and humiliating an opponent. Even today, Sundowns are known as “Bafana Ba Style,” meaning “Boys with Style,” and the humiliating continues: in 2012, they set a South African record by beating Powerlines FC 24-0.

True to his own nicknames, Mahobe threw money around. Screamer remembers: “Mahobe was very generous and would always encourage us to tell him whenever we had financial problems, and he would just splash the cash.” High performing players were rewarded with new luxury cars and other expensive bonuses.

For many years afterwards, the South African soccer press and fans were still buzzing over the news that Mahobe had flown his entire 1986 Mainstay Cup winning squad, and their wives and girlfriends, on an all-expenses paid trip to London to watch the FA Cup final between Liverpool and Everton (Johannesburg-born Craig Johnson scored one of Liverpool’s goals in that 3-1 win). Mahobe also had plans to take his squad of “Brazilians” to Brazil, but could not obtain visas as Brazil boycotted South Africa. There were also rumors, never confirmed, that Mahobe—in contravention of the sports boycott—had organized “practice” games for his team with English clubs while there.

With Screamer at the helm, Mahobe’s team became a force in South African soccer. Between the money, the bonuses, the aggressive signing strategy and the “shoe-shine and piano”, it wasn’t long before Sundowns were challenging the hegemony of Chiefs and Pirates on the field. Between 1983 and 1990, Mamelodi Sundowns won four cup tournaments and three league titles. Mahobe had completely changed the model for running a South African soccer club, and the trophies hadn’t been slow in arriving.

Not for nothing was the team’s motto “The Sky’s the Limit.”

“WE DIDN’T KNOW WHERE THE MONEY WAS COMING FROM UNTIL A LATER STAGE, WHEN EVERYTHING BECAME CLEAR”

Journalist Lukanyo Mnyanda likens Mahobe’s achievements to those of Manchester City’s Abu Dhabi owners, who have propelled the club into the European elite in just a few short years through grand ambitions matched by vast spending. Siviwe Minyi is a friend of mine, and a Kaizer Chiefs supporter (he also grew up in a township in Cape Town). He told me: “I guess, had he carried on, Mamelodi Sundowns would be the team in South Africa, modeled along the lines of Real Madrid or Barcelona.”

This view is largely borne out by the facts. In the 1980s, the South African game (especially what became the NSL), was making a transition to the television age of big-money sponsorship deals. Before this, stadiums were dilapidated, the quality of officiating low and claims of match fixing were rife. Audrey Brown, now a broadcaster with the BBC and a Pirates fan, remembers how Mahobe’s purchase of Sundowns coincided with vast improvements in the match experience: Saturday afternoons in South Africa became more accessible, cleaned-up, “family-friendly spectacles”. “Soweto’s elite, bolstered by people moving from other parts of the country into areas like Hillbrow, Yeoville, Berea, Mayfair, went to these matches. They were places to be seen, unlike in the past when violence was a strong likelihood and no-one in their right minds would take their girlfriends, let alone their children to a stadium.”

On the cusp of the television rights boom and with Mahobe at the helm, Sundowns’ future looked rosy. But as Screamer wrote last December: “We didn’t know where the money was coming from until a later stage, when everything became clear.”

Mahobe, ever the flamboyant and generous bon vivant, gave little away with regards to where he was getting all his cash. He had established himself as a hugely popular figure: the sight of a black man of means being generous with his largesse was enough to make him a legend in the townships around Johannesburg and Pretoria.

The soccer writer Njabulo Ngidi was young when Mahobe was running Sundowns but vividly remembers stories his father, a die-hard Pirates fan, told him about Mahobe. “He was loved by soccer fans. Soccer is among a few things that brought a semblance of sanity in the lives of black people then.”

Mahobe was a man of extravagant tastes, and it was this that would prove to be his undoing. He owned a racehorse and was the first black member of the Newmarket Race Club in Johannesburg. He also owned a fleet of expensive cars and houses. In 1987 he wanted to buy a new Mercedes Benz. All that was needed was for his bank to make a direct transfer to the manufacturer. Usually, Mahobe’s transactions were handled by a trusted bank employee: none other than Ms. Snowy Moshoeshoe.

That day Snowy happened to be off work. That’s when the bank discovered something else. Mahobe and Moshoeshoe were lovers and had been defrauding the bank for four years to the tune of about $3 million—a vast sum in those days. The scheme was simple: Zola would put in requests for bank transfers—modest amounts at first and later larger sums—that Moshoeshoe would access from unsuspecting clients’ accounts. With that money, Mahobe bought himself lots of expensive things, including South Africa’s most exciting soccer club: Mamelodi Sundowns.

Moshoeshoe was arrested, while Mahobe went on the run to Botswana. When he was caught and brought back to South Africa one year later, Mahobe made up some excuses to the court about how he thought Moshoeshoe got the money from farms and properties sold in Lesotho by her royal relatives.

In 1989, a judge sentenced Mahobe to 16 years in prison. He only served five. Moshoeshoe, sentenced to 10 years, eventually served only four. Even as they were both in jail, the very public love story of Zola and Snowy continued. In 1991, Mahobe placed a notice in a local newspaper: “My Valentine Snowy, if you think there is anybody who loves you more than I do THINK AGAIN. Zola.” Snowy and Zola reunited after they both came out of prison. In 2010 Snowy died of cancer.

To fully appreciate Mahobe’s impact on South African soccer, you must follow the fortunes of Sundowns and their former owner after he was sent to jail. After Mahobe’s arrest, the club was handed over to the bank he defrauded, Standard Bank, who sold it to Abe and Solly Krok, two white Pretoria businessmen who were identical twins and always dressed alike. In one of those great South African ironies, the Kroks had made their fortune marketing and selling skin lightening creams to black people since the early 1960s. The Australian reported in 2009 that their products, used by one in three black South African woman, resulted in “irreversible and disfiguring skin damage among many users.” Later the creams were “pulled from the shelves and a key ingredient, hydroquinone, has since been banned by the US Food & Drug Administration after animal tests found it to be carcinogenic.” With Mahobe behind bars, Sundowns’ playing gear was now plastered with ads for the Kroks’ pharmaceutical products, such as Dettol, Disprin and HeMan. (In a further irony, the Kroks also later financed the construction of the Apartheid Museum to the south of Johannesburg as quid pro quo to securing a gaming license and build a casino next to the museum.)

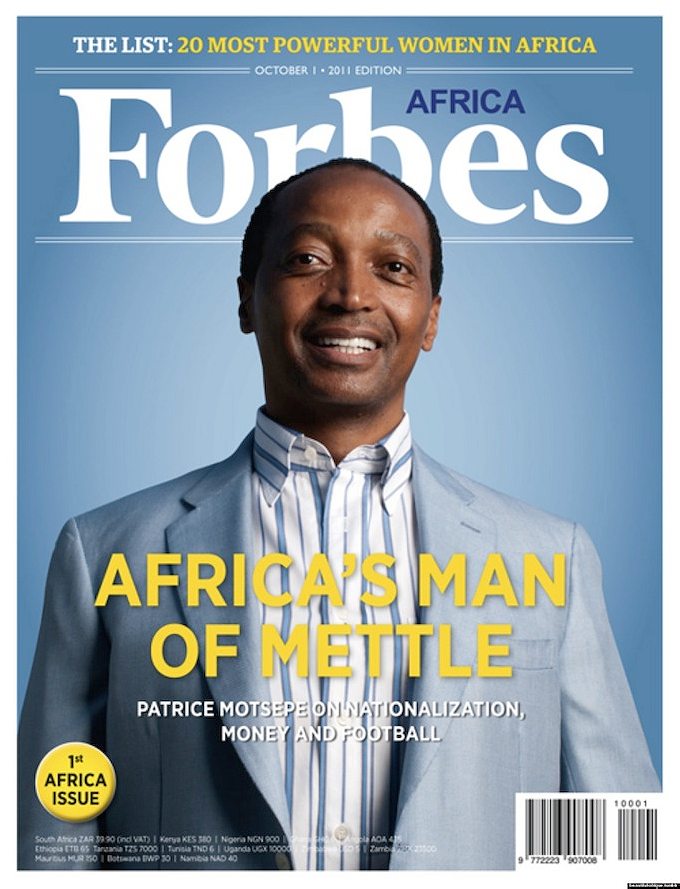

When Mahobe was released from prison, Sundowns fans clamored to have him back on the team as a director, but the Krok brothers said they could not “accommodate” him. The club grew and was eventually sold, in 2003, to Patrice Motsepe, a politically-connected businessman and the first black South African to be included on Forbes’ annual list of billionaires, where he has remained consistently for the past six years. Motsepe is the new South Africa’s version of an oligarch, with close ties to the ANC and huge mining interests.

Motsepe has tried to bring back the Mahobe glory days. He signed Katlego Mphela, a player remembered for his 2009 freekick goal, from 25 yards out, against Spain in the 2009 Confederations Cup. Motsepe also signed a number of top coaches, who all failed at the club: Henri Michel (after he took Cote d’Ivoire to the 2006 World Cup), the great Bulgaria and Barcelona forward Hristo Stoichkov, and former Dutch international Johan Neeskens. The latter had to be personally rescued by Motsepe when a group of Sundowns fans blamed him for the team’s poor form in 2012 and attacked him after a match.

It was Motsepe who brought Mahobe back in from the cold. Some reports during his post-prison years listed Mahobe as a “silent director” in the club and he was spotted at matches even offering his opinion to journalists about Sundowns’ changing form. In December 2013, Motsepe told the national broadcaster that the club “will be eternally grateful to Mahobe,” who, he said, had “laid the foundation for the development and success of Sundowns.”

Motsepe’s statement may appear to be merely polite, but what is striking about all this is how Mahobe is remembered among ordinary people, the admiration retained for him, despite his crimes. When he died, the South African Broadcast Corporation (SABC) described Mahobe’s passing as “a loss for the South African sports fraternity” and credited him “for transforming the Brazilians into one of the biggest clubs in the country.” This time around Shakaone spoke slowly and seemed genuine when he compared Mahobe’s actions to people actively resisting Apartheid.

Lukanyo Mnyanda remembers Mahobe’s virtues overshadowed his vices in the public eye. “I don’t remember any big sense of outrage when his scheme was exposed. The adults around me were more interested in the glamour aspect of the whole story and the daring nature of the crime, rather than great moral judgments.”

Some fans in the townships felt that as Mahobe stole from rich whites, his crimes weren’t irredeemable. South African soccer fans, then as now mostly black, venerated Mahobe. For them, he was a self-made man, who had achieved fame and fortune despite Apartheid. One commenter on a soccer website dubbed Mahobe “the black Robin Hood” and some Sundowns supporters prefer him to Motsepe, the archetypal black billionaire of the post-Apartheid period. Ngidi told me that to his father, Mahobe was “someone who was taking money away from the racist government to his people who were marginalized.”

In this view, Mahobe has come to represent a kind of black autonomy during Apartheid. Siviwe Minyi described Mahobe as “a black man who was not shy in leading a soccer brand based in a township. Although this was not unique, he was different. He had a business-like approach to this. It is no wonder that when we speak of Mahobe, we speak of him as a hero. Very few of us take the seat of judgment when a conversation about Mahobe emerges.”

But Mahobe is also seen as an exemplar of another legacy of South African football dating back to the 1980s: that of the deep-seated corruption and malaise in the local game. That some of the greatest steps forward in South African soccer culture came about as a result of a bank heist is an irony too tough for some to swallow.

In some ways, Mahobe merely reflected the times, and he laid the foundation for the success Sundowns have enjoyed down the years. The club dominated South African soccer for most of the 1990s and is still one of the “big three”. Sundowns’ greatest owner is dead, but the story of the club and his role in its meteoric rise may turn out to be more illuminating for how we understand South African sports and society than what we learn from the neat binaries presented by movies like Invictus.

Broadcaster Audrey Brown articulates more clearly why the fascination with Mahobe and Moshoeshoe’s actions: “I think Zola and Snowy—sophisticates—were a reflection of this confident, surging elite who knew that apartheid was being forced to capitulate by black people who—all over and all the time—were refusing to accept white authority. When news of their fraud broke, there was very little unease about the illegality of it.” She continues: “South Africa as a modern state is predicated on illegality and theft and things like stealing from white owned shops or selling through ‘the back door’ were long established practices in Johannesburg. So Zola and Snowy were just taking it to another level. Not that this wasn’t contested: I remember huge arguments within my social circles about whether or not this should be applauded or not. The feeling was that this was wrong, but so what? It was another defeat for the ‘regime’.”