Rachel Williamson on the efforts of a group of artists and activists trying to restore an apartment from the golden age of Egyptian cinema.

In December 2012, engineer-turned-filmmaker Mamoon Azmy found himself dangling perilously from a first-floor ceiling beam, contemplating his good fortune. True, he was suspended five meters above an open-air market, but the fear of falling was overcome—somewhat, at least—by the fact that the floor of the apartment through which he’d just fallen was the place that spawned Egypt’s glorious cinematic past.

A few moments earlier, as the rest of the crew of volunteers battled dust and giant cockroaches in the other half of the twelve-room suite, Azmy, 32, was filming the early stages of restoring this derelict space, a former movie studio and office belonging to one of Egypt’s most powerful film families. He was capturing light shining through crumbling plaster onto honey-colored brick, the first beams of renovation after 50 years of neglect.

Then the floorboards broke under his feet. He tossed the camera to safety, and even as painful injury seemed inevitable, he thought: all good things in life require sacrifice. On this day, at least, no great sacrifice was required. Swinging his legs over the beam and back inside, he lived to film another day.

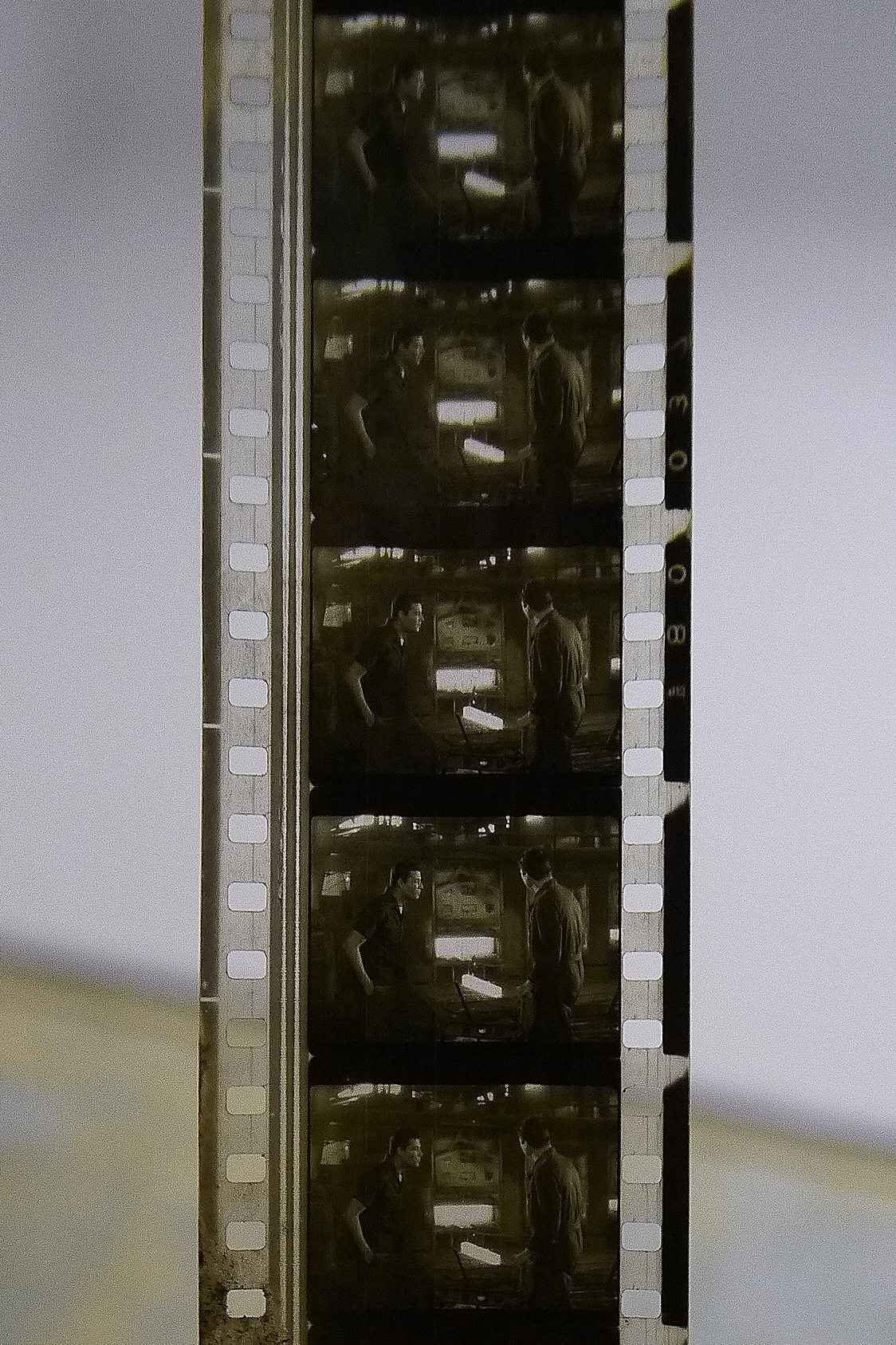

For years, Azmy and his artist and filmmaker friends had been lounging in the open-air cafe beneath the apartment, never realizing that above them was a trove of forgotten film reels and scripts from the earliest days of Alexandria’s cinematic history. Back then, he had no idea he would soon abandon a hated career as a heavy industry engineer and in order to help restore Egypt’s film history.

Egypt is currently suffering maladies that seem far more acute than a lack of artistic opportunity.

Today, Azmy is the filmmaking coordinator of a group of young professionals and volunteers in Alexandria called the Gudran Association for Art and Development. Gudran is a coalition of artists from all disciplines whose core belief is that art is key to social transformation. The group believes that by taking art to the people—commissioning a street art project in Alexandria’s alleyways or turning an unused air-conditioning building into a recording studio—they can compel Egyptians to examine their lives and the world around them in a creative way.

It’s a sweet, if perhaps naïve, idea. Egypt is currently suffering maladies that seem far more acute than a lack of artistic opportunity. The media here is helping turn Egyptian against foreigner, Muslim against Muslim, and everyone against men with beards, otherwise known as Muslim Brothers and Salafis. Reported violence against women is rising. High youth unemployment (over one-third of Egyptians under 29 are out of work) is preventing young people from an Egyptian social necessity—marrying—and creating a legion of frustrated young men with too much time on their hands. Homelessness, especially among children and young women, is rising fast.

But problems that deep exist on many levels, and for the artists of Gudran, the root of at least some of what ails Egypt is social and intellectual claustrophobia. In Alexandria, they are hoping to preserve some of the city’s historic buildings as creative spaces for artists, instead of letting them be demolished to make room for shopping malls or apartment blocks. More space for artists means more art, which means a bigger audience to inspire to think about, and maybe act on, Egypt’s many challenges.

Alexandria was the birthplace of Egyptian film.

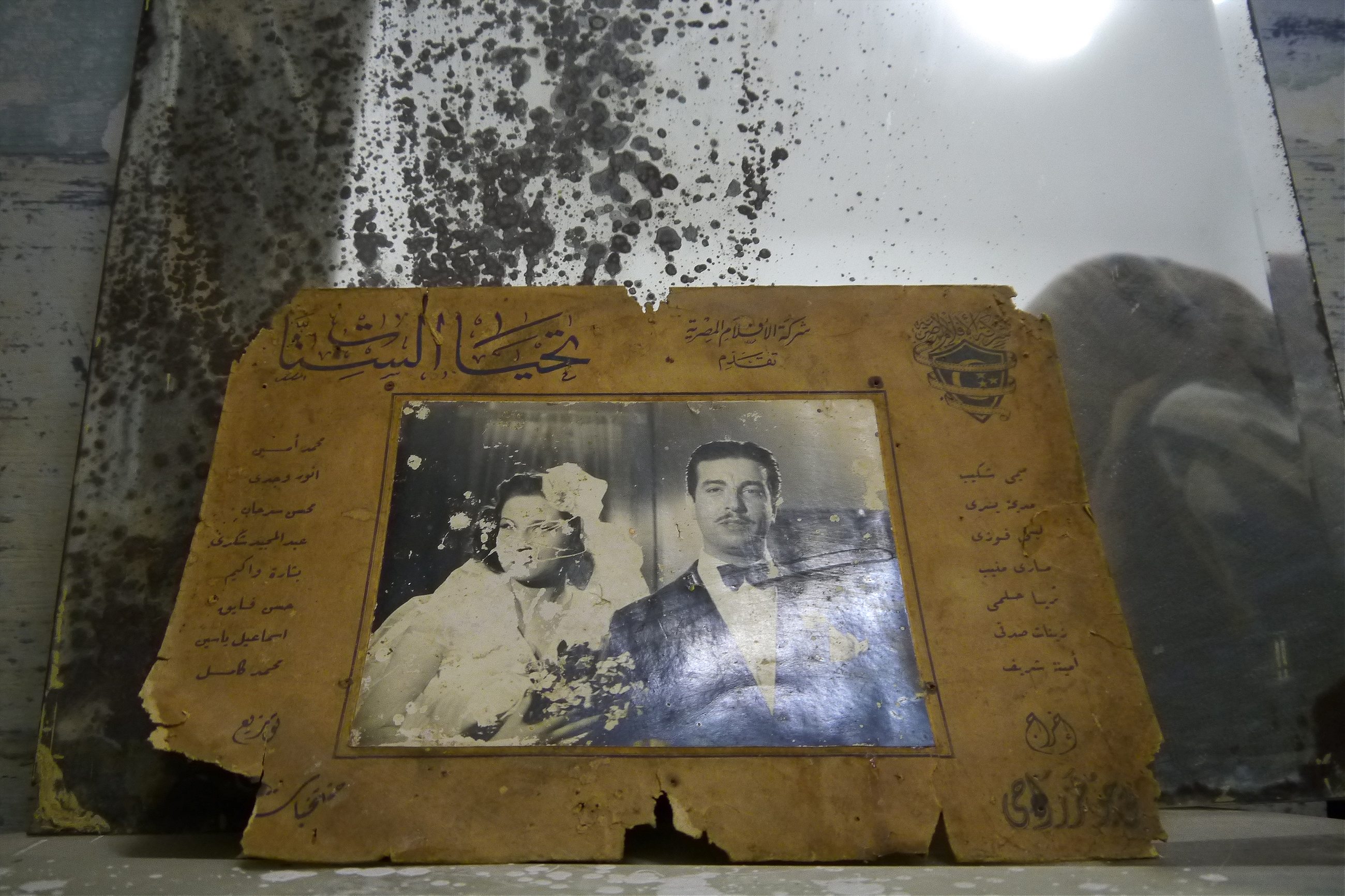

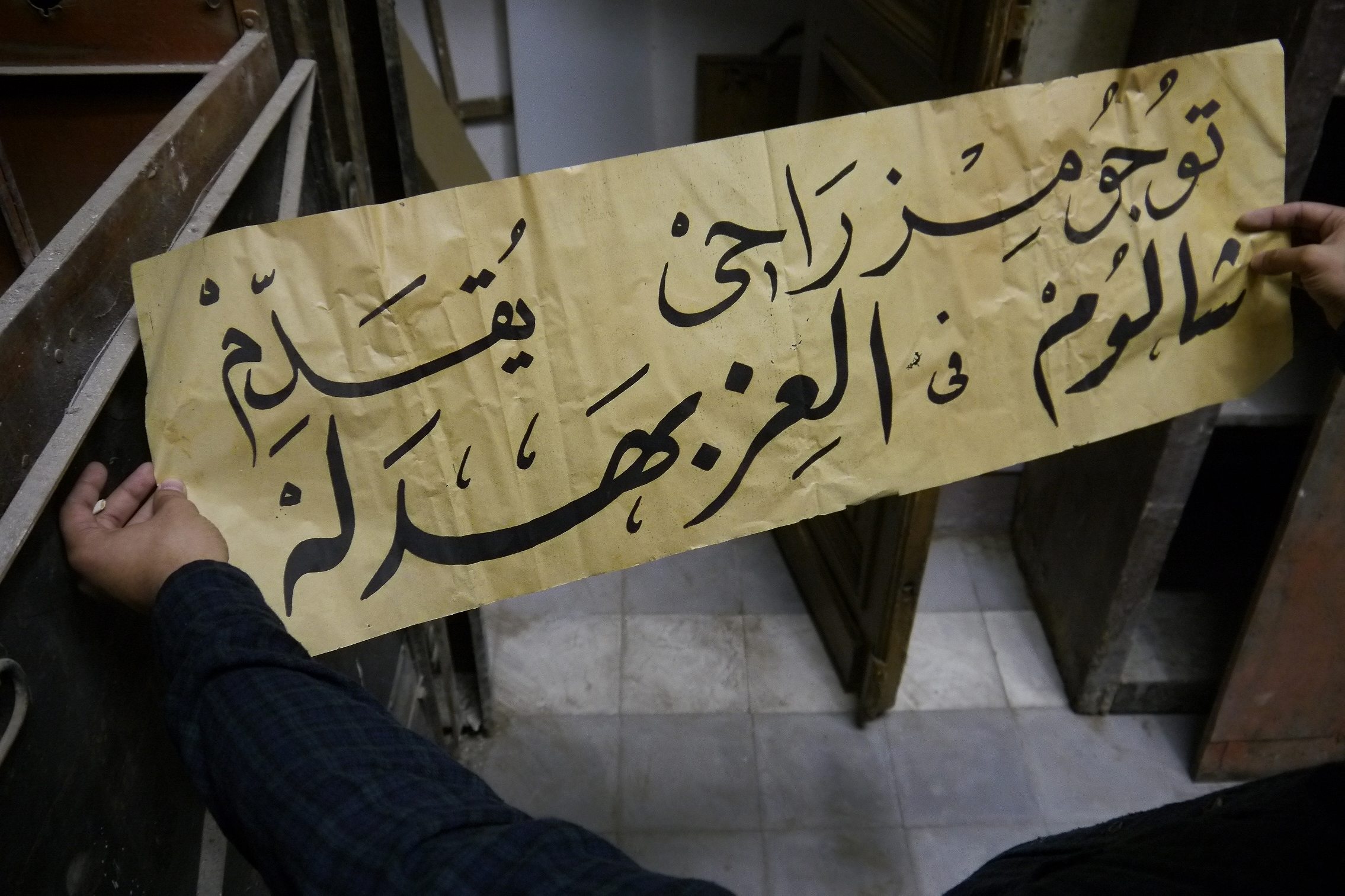

Gudran’s latest project is Wekalet Behna, the 12-room apartment once at the glitzy heart of Egypt’s cinema industry. Armenian immigrant Rashid Behna was the driving force behind the launch of Behna Brothers, a 1930’s movie production company that later became a major film distributor. The family used film as a conduit to money, fame, and an entrée into cosmopolitan Alexandria society.

Alexandria was the birthplace of Egyptian film. Immigrants with close ties to their home countries imported new ideas and film equipment to the city, and popular Egyptian singers and stage actors, particularly women, jumped onto the new craze. Cinema historian Ahmed el-Hadari said in an interview with Alex Cinema that women like Aziza Amir leveraged their admirers to fund edgy, new ideas, such as long feature films, that male producers and actors wouldn’t risk doing.

In 1961 the socialist Nasser regime nationalized the business.

But the wealth and status the Behnas craved and eventually attained was also the family’s downfall. In 1961, after the company became the biggest film distributor in the Arab world, the socialist Nasser regime nationalized the business. In 1978, heir Basile Behna began a legal fight that didn’t end until 2010, when the family finally won back the keys to the Alexandrian apartment.

After forty years of neglect, the restoration job, which began in December 2011, was daunting. But everything was ready by the March 15 launch—almost. Up a flight of worn marble stairs from the Ali El-Hendy cafe, there is now no sign of the foot-long rats Azmy says infested the apartment, or the giant black cockroaches that amazed even an exterminator sent by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Instead, Gudran program manager Abdalla Diaf says the group continues to find treasured artifacts from a bygone era. In an old desk drawer, they found copper stamps for making movie posters, displaced long ago by computers and printers; in a wooden box, they discovered the acids early producers used to fade a scene to black.

“We found an incomplete copy of El Hanem (The Lady),” Diaf says. “I don’t think this film remains in Egypt.” They didn’t even know what they had on their hands until they brought in an old projector that could screen the old 35mm films.

Diaf has been working with Gudran since 2004. Sauntering into the interview with aviator sunglasses and a two-inch afro, Diaf looks every inch the activist-artist. But he’s not the kind of activist that shouts his message from a stage on Tahrir Square. His message—and Gudran’s—is one of “festive resistance,” an idea creeping into protest movements around the world. Festive resistance, according to Diaf, is partly the artistic credo of pushing people to question their certainties and partly the idea that social change can come from artistic protest. Basile Behna met Diaf at a party in 2006, and in 2011 convinced him Gudran should take on the restoration work at the apartment. Behna shared the view that art and culture is the “only way” to change a society, and he especially liked the idea of festive resistance.

“If we demonstrate against the government the police will arrest all of us,” Diaf says. Instead, Gudran went to a neglected fishing district of Alexandria called El Max. They reinvigorated the village by developing the local arts and craft sector. “We changed the point of view of the local authorities to not destroy the area,” Diaf says.

Diaf sees the Behna project as another way Gudran can effect social change, this time via the independent filmmakers who will use half of the apartment as a studio. There are two goals. First, rescuing and old building and giving it new use. Second, supporting independent filmmakers.

Ahmed Hassan is head of Save Alex, the organization dedicated to preserving heritage buildings in Alexandria. He says the Behna project will be a model for how Egypt can reuse and readapt these buildings to contemporary use, without bulldozing the history they represent. Alexandria “has a very long history and is well known for its richness and cosmopolitan society,” Hassan says. The city’s history as a social melting pot is displayed in these buildings.

But since the 1952 Nasserite revolution, the country has become less tolerant and less appreciative of diversity, Hassan says, which is why encouraging independent and thought-provoking filmmaking is crucial. Ahmed Nabil, a filmmaker and exhibitions specialist at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, says Egypt’s independent films tend to favor more liberal and modern ideas about society. The Behna project opened just as Alexandrian film was taking off again, with the first feature-length film to be made in the city, The Mice Room, debuting at the Dubai Film Festival in December.

Back at the apartment, Amzy remembers the first time he ventured inside its light, airy corridors. It was the end of 2012 and for 35 minutes he had stood spellbound admiring the light and decorations coming through the tall windows. The room was closed up and dirty, and he’d been asked if he wanted to use his engineering skills, learned through a job he loathed, to restore it.

Initially he resisted, but the aesthetics of the place changed his mind. The project was too important, the subject too beautiful to turn down. “I decided, it’s my pleasure to work again as an engineer in a place like this.” If you’re going to build a new Egypt, after all, you’re going to need engineers and filmmakers alike.