An American lawyer-turned-photographer visits Guantánamo Bay’s residential and leisure spaces to explore the human experience of living there.

It was a Monday afternoon when Debi Cornwall landed in Guantánamo Bay. A guard checked her passport but didn’t stamp it–she was technically still on U.S. soil. After eight months of waiting and a thorough background check, she was finally set to start shooting her project “Gitmo At Home, Gitmo At Play.” She knew she would have limited access to prisoners, but she still wanted to tell the story of what she saw as an injustice: the one of men being held prisoners for years on end without formal arrest, without trial, without transparency and without conviction. But being on base, she also got to spend time with their captors, which broadened her perspective, and her project. She met with R&K in Brooklyn.

Roads & Kingdoms: This is your first photo project in a long time, why return to photography with a story on Guantánamo?

Debi Cornwall: I spent my career as a lawyer doing civil rights litigation on behalf of wrongly-convicted people across the United States. I wanted to look at some of the same questions but from a perspective that was less one of fighting for a cause than it was inviting people to look at what they might not have otherwise chosen to. Given that more than half of the remaining 149 prisoners in Guantánamo Bay were cleared for release years ago and there seems to be no real movement towards closing it, and that Guantánamo is this unseen mysterious place for Americans, it seemed like the perfect first project.

R&K: What were you expecting to see?

Cornwall: I wasn’t sure what to expect really, I had been to many prisons as a lawyer, but the experience of walking into the three prison facilities that I toured on my first trip and then a fourth on my next trip were very different from anything I’d experienced before. You don’t go through security, for example, when going to a prison on Guantánamo Bay, because the fact that you’re on the base means that you’ve already been cleared. There was a high level of tension and a large number of military escorts in addition to the one who was with me constantly throughout my stay there.

R&K: A lot of the visuals we see of Guantánamo are the same stock photos of barbed wire and orange jumpsuits. Your project is very different…

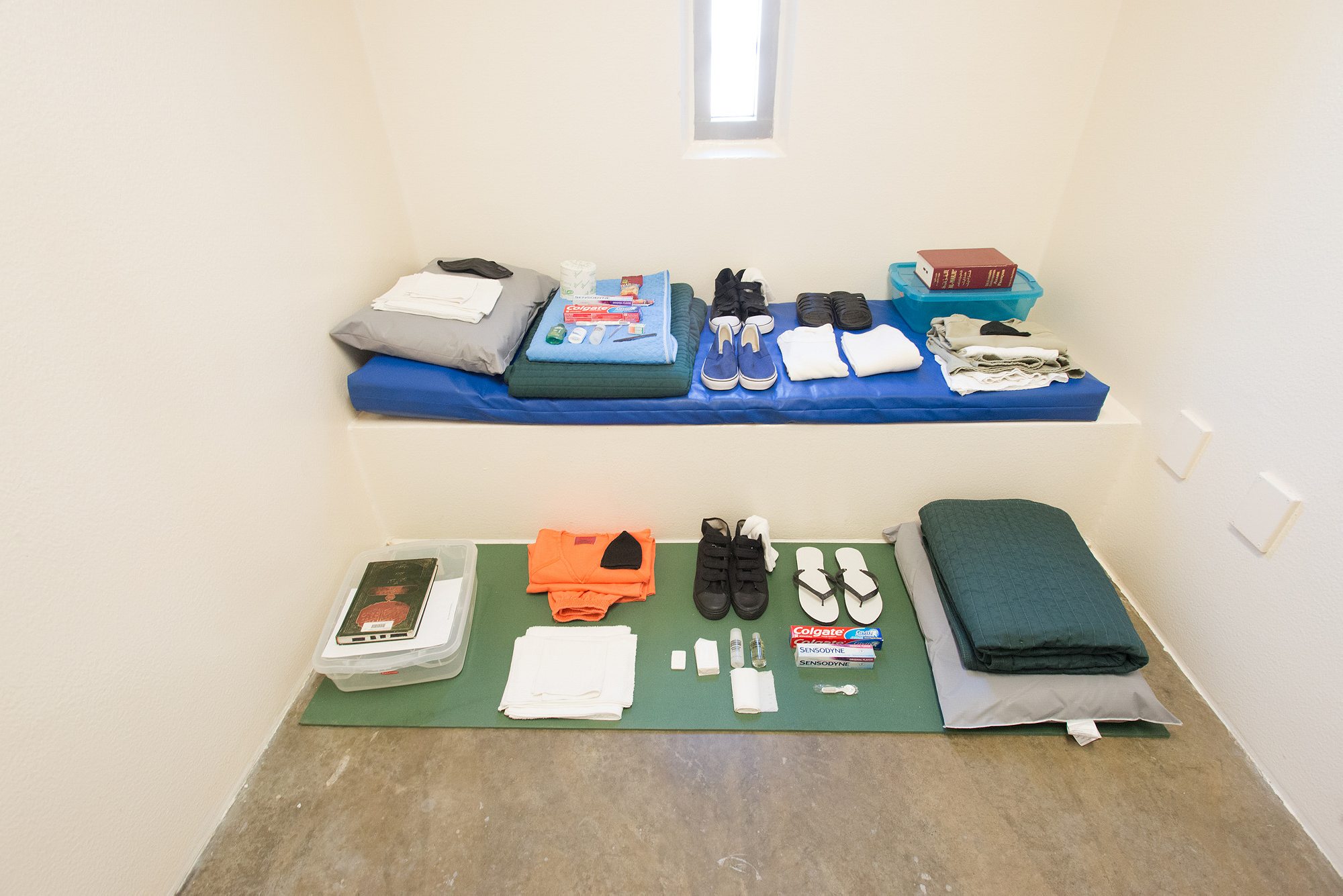

Cornwall: Exactly. I think we all have those pictures in our head. I wanted to look at it more metaphorically. So my strategy for “Gitmo At Home, Gitmo At Play” was to look at residential and leisure spaces for both detainees and guards as a window into the human experience of life there. Particularly because we’re not allowed to photograph anyone’s faces, and how do you tell any human experience without being able to photograph someone’s face?

R&K: That’s one of the things I was fascinated by in these photographs. I understood that it was probably a constraint and that you weren’t allowed to, but that gave an effect of dehumanizing this very clinical place and so it brought the question of who we are and why do we build these kinds of places?

Cornwall: Those are exactly the kinds of questions I’m hoping people will ask and it’s been really exciting for me to get the work out there into the world. Since the work first started being published, I’ve been contacted by former military personnel who’ve said “these photos capture my experience of the place, it’s a lonely, haunted place” but also by high school students doing term papers who want to talk about what it’s like to be there. And that’s really gratifying.

R&K: You had to show your photographs to get them cleared in order to publish them later. Do you think the military was surprised by the photos you took?

Cornwall: I think so. Each four-day media visit involved only two days of shooting. And at the end of each day, your chip is taken out of your digital camera and reviewed image by image by military personnel. Any image that violates any of the many, many regulations is either cropped or deleted. No faces, no surveillance mechanisms, no landscapes that show defensive positions… I think the reaction to my images on base was that they were not remarkable. You know, most journalists who go are looking for the iconic prison shots and I was not trying to do that.

R&K: You shot a lot of very American objects and symbols. What did it make you feel as an American to be there?

Cornwall: It was disorienting to see so many icons of “normal American life” in this place that did not feel normal or American. And that disconnect, that discomfort, is part of what I was trying to show in my pictures.

Everybody is counting the days until they can leave–although the prisoners don’t know that they’ll ever be able to

R&K: Can you describe your relationship with the people who escorted you? How close did you get to them?

Cornwall: It’s interesting that you ask that question. I’ve been there twice so far and my first visit coincided with the arrival of a new Public Affairs team from Florida. My most recent trip was near the very end of their deployment and so over the course of the eight days that I spent with this team, we really did get to know each other. You’re driving around the base with a 15-miles an hour speed limit, so you talk, you get to know each other, and I really appreciated that the people I met there opened their lives to me. It opened my eyes to the military experience, which frankly wasn’t something I’d thought much about. Now as I think about where the project could go from here, I’m reaching out to veterans who’ve been posted there to talk to them more about their experiences, to see if they’re willing to share snapshots that they’ve made on base because they’re an integral part of the story of the human experience there.

R&K: For me, the most surprising photos were the ones of the stadium and of the pool, I just didn’t imagine that soldiers could have a normal life there… I guess I didn’t think about it before.

Cornwall: I don’t think I did either and one of the first things that was said to me when I arrived on my was: “this is the best posting a soldier can have. There are so many fun things to do here.” So I said: “that’s my theme. Show me evidence of the fun and I will document it.”

R&K: And did you find it?

Cornwall: I found opportunities for fun, from the pools and the golf course to the open-air movie theater and the bowling alley. But when I was shown these spaces, they were empty, or people were turning away from the camera.

R&K: This is a project of contradictions: it’s a prison in a tropical paradise, and there’s the contrast between the lives of the prisoners and the lives of the soldiers.

Cornwall: That struck me as well. While you can never equate the experience of the prisoners with the guards, there is one point of human connection between them: nobody has chosen to live here. And for all of them, as far as I can tell, life is about order, it’s about routine, it’s about following the regulations and there’s a tedium of boredom for everybody. Everybody is counting the days until they can leave–although the prisoners don’t know that they’ll ever be able to.

R&K: Did you have any interactions with the prisoners?

Cornwall: On each prison tour, media is shown to empty spaces. There’s one opportunity for journalists to see prisoners and that is at a great distance through a two-way glass that is darkened. That was both something that didn’t fit into my project and also something that made me as a human being uncomfortable because it was all the more dehumanizing to be peering at human beings who didn’t know you were looking and had no choice in the matter.

R&K: Do you hope to get more access to prisoners?

Cornwall: I would love to be able to take portraits of prisoners while they are still there or after they have been released, and that is something that I’m exploring right now.

R&K: How did you feel in this new contemplative role? You were a photographer there, not a lawyer…

Cornwall: While the approach is completely different, both professions are about storytelling in the end. Just as I looked for facts as a lawyer that would tie a case together for a jury, I looked for images at Guantánamo that would be emblematic of a larger story about what is happening there. As a photographer, I’m still feeling out where to land between art and advocacy. I think one of the things we don’t do as lawyers is change people’s minds. It’s really not just lawyers, it’s anything any of us feel passionate about. We feel strongly and we fight and we yell and we try to out-argue the other side and on some fundamental level we’re not getting to the human truth of whatever the issue is when we do that. So as a photographer I’m more inclined to look at the reality for both sides and invite people to look in hopes that they might start seeing the issue from a new perspective. I’d like to start a new kind of conversation.

R&K: Have your feelings about Guantánamo changed?

Cornwall: I think what’s changed for me is becoming more curious about the experience of those who are posted there as guards. But ultimately I still believe there is an injustice happening in this place. And that for whatever its flaws, our criminal justice system has the capacity to process these cases and it’s critically important that we live up to our standards of justice, particularly in cases like September 11th. It feels as though our fear has taken over our ideals.