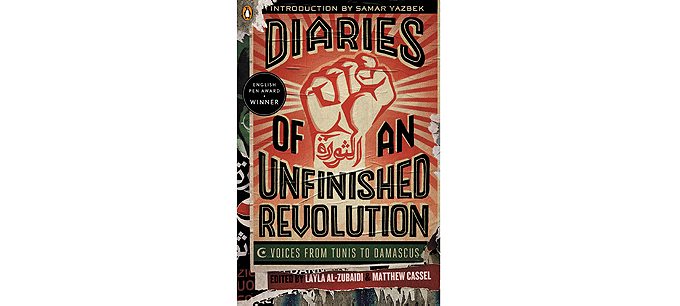

An unfinished revolution.

Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Books, a member of Penguin Random House Company, from Diaries of an Unfinished Revolution, edited by Layla Al-Zubaidi, Matthew Cassel, and Nemonie Craven Roderick. “Wishful Thinking” copyright (c) 2013 by Safa Al Ahmad.

‘I’m Saudi. I’m sorry.’ It’s a phrase uttered at every introduction in Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen, not so much in Libya. Whisper it to myself in Bahrain. As I walked into Amal’s house in Sanaa, my friend greeted me warmly and apologetically declared she was boycotting Saudi products. She burst out laughing: ‘Then I remembered I’d invited you over!’

The other guests were taking off their abayas, putting on make-up and relaxing after their long workday. ‘Why are you wearing all black? Go put on something colourful!’ Amal demanded of one of her friends. ‘Look in my closet!’

‘When will you have your own revolution so your government forgets about us?’ asked Nabila. ‘Do you need us to export some of our revolutionaries?’ joked Belqis.

Although said light-heartedly, the words dealt a heavy blow, hitting a raw nerve I have been nursing for a while. The women were jovial, laughing loudly and greeting each other with hugs and kisses. Then we all went quiet and stared at Amal’s newly acquired piece of art hanging on the wall of her majlis: a large painting of a little girl and a woman sitting sideways, each covered in a shroud. ‘It means we are buried alive from childhood,’ she said. ‘Take it down!’ shouted the women, ‘It’s too depressing to look at while chewing qat.’ It was chilling: a bland light blue background and the two females covered in white, like ghosts.

We sat on low cushions in Amal’s welcoming olive green living room, drinking milk tea, her cat purring from outside the window as it peered at us contently. I was trying not to swallow the qat, and just chew it instead. Holding a conversation while chewing is a talent I don’t possess. We talked about the state of the Yemeni revolution, electricity blackouts, sex or lack thereof. I felt at home. Then another question hit me: ‘So when will they allow women to drive?’ A reminder, I was not at home.

Even Yemen, one of the poorest countries in the region, is ahead of Saudi Arabia when it comes to women’s rights and civil society. Saudis often look down on Yemenis, see them as inferior. Sitting in a room full of intelligent, brave and independent Yemeni women talking about revolution, a real one happening on the streets, which ultimately toppled their dictator, it was evident they were decades ahead of us.

The entire Arab world was engaged in a collective uprising for its freedom and dignity and my countrymen and women were begging for scraps. Dancing around the edges of systemic problems facing the kingdom.

‘Close your abaya!’ shouted a short man in his signature short white thobe, bright blue shoes and white high socks. He looked more like a fat, overgrown child with a nappy beard than a grown man. I was easily two heads taller than him and felt a strong urge to swat him away, but he continued to buzz around me. ‘Close your abaya! I am from the Haya!’ he exploded, declaring the obvious, that he was from the detested religious police, pompously called ‘The Organization for the Prevention of Vice and the Promotion of Virtue’.

I gave him a look of disgust.

I was annoyed and confused. Why is this idiot following me? My abaya was not only closed but a bit too long and under it was a long white skirt and my hair was covered. Anger welled up, choked me, my hands started to shake, not from fear but repressed, bottled-up, festering anger. Saudi Arabia forces you to see yourself based on your gender. Living in Saudi is infantilizing.

It would have been a comic scene if it didn’t have possibly dire consequences.

I weighed my options between punching him in his expansive stomach, or continuing to ignore him. My anger grew as I walked. People I passed stared at me and then at something behind me. He was still in hot pursuit. It would have been a comic scene if it didn’t have possibly dire consequences. I walked into a make-up shop and pretended to buy something. He walked in and demanded the sales person not sell me anything. My face burned. ‘Do I look naked to you?’ I burst out. He looked at me blankly, through me. I wasn’t human to him, I was something to be despised, to be corralled, like sheep. Cover up and shut up. The so called ‘religious’ police did not deem me ‘appropriate’ and he had the power of the State, with which he could randomly humiliate and terrorize an entire population in the name of Islam.

‘Close your abaya,’ he barked again. He decided to call for back-up on his walkie talkie.

How advanced he was, using technology to enforce the most primitive of constraints. ‘I will not talk to you! Where is your guardian?’ he demanded averting his gaze from mine as I got into his face, shouting, ‘Where is your guardian? Who gave you the right to harass me?’

I was surrounded by three religious thugs with crackling walkie talkies and hovering security guards, a reminder of how fast things can go badly in Saudi Arabia for no other reason than expressing yourself, speak up and they will try to intimidate you, crush you. And if you are female – your appearance alone is enough to get you in trouble.

People around me froze, staring.

I went in search of a witness to the unwritten part of my history. Someone to explain, with more than a few pages, a monumental year in Saudi Arabia, when an uprising gripped the entire country. Abu Ali agreed to talk to me about his memories of 1979. He was a teenager then, but his affluent father had bought him a white Toyota Cressida. He used it to drive his friends to a big demonstration in Qatif. It was Ashoura and a revolution was taking place in neighbouring Iran. Spirits were high, and illegal flyers were stencilled and circulated to declare the uprising through Husainiyas and mosques in the city. ‘We had no clear leadership, some of the religious men tried to stop the demonstrations, and few supported it,’ said Abu Ali. It mirrored the current situation. We refused to say ‘down with a person or in support of another’, but ‘down with injustice and long live freedom’. But events were not organized, and within a short period the National Guard arrived and killed the first protester. Diesel was set ablaze in the streets by residents to stop their advance. Hundreds were arrested and tortured, many went into exile.

The situation was much more dangerous for the Saudi regime that year, for the uprising in the East coincided with another much more lethal Sunni uprising in the West and an attempted takeover of Mecca.

Both were brutally crushed. And history repeated itself like a broken record. Scratching a looped tune of loss and desire for freedom.

‘Why are you letting the youth commit your mistakes?’ I asked Abu Ali.

‘They believe we failed. They don’t want to learn from us. They are not only protesting against the government, but against the past as well.’

[Header photo: “Hustle & Bustle” (King Fahad Road in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) by Wajahat Mahmood]