A photographer traveled throughout Papua New Guinea documenting various forms of violence towards women, and some of the men responsible.

Vlad Sokhin is a big Russian with a penchant for understatement, which could explain why he says he’s comfortable working in Port Moresby, one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Sure, he’s been held at gunpoint a few times, but it hasn’t stopped him from coming back to Papua New Guinea nearly a dozen times in the last couple of years. First on his own and then with the help of the UN and other organizations, he traveled throughout the country documenting various forms of violence towards women (“meri” in the local language) and some of the men responsible. His first book, Crying Meri, will be released in October 2014. He joined R&K from Dili, East Timor.

Roads & Kingdoms: What brought you to Papua New Guinea?

Vlad Sokhin: I had read reports about the very high level of violence against women there. Not only domestic violence, but also street violence, sexual violence, sorcery-related violence [in case of an unexpected death in a village, residents often accuse a woman of sorcery, usually a relative of the dead person, and torture her, forcing her to confess that she is a witch]… I was shocked. I decided to go and see what I could do as a documentary photographer. I pitched the story to several magazines but it seemed no one was interested. I went anyway. I got some material, photos and stories, and submitted this work for the FotoEvidence Book Award, where I was a finalist. I didn’t win, but someone from the UN saw my work and the OHCHR office in Papua New Guinea asked me if I was interested in collaborating. So I returned and started working with them and a lot of different organizations like UN agencies, NGOs, charities… They were calling me all the time by that point, so I made Port Moresby my base.

R&K: Why were you interested in documenting violence against women?

Sokhin: I think, for me, it was… Papua New Guinea, if you hear of this country, people imagine traditional tribes, beautiful masks, dances, festivals… Which is all there, it’s true. But no one talks about the other side of life, the one that is horrible for the women of the country.

Once, [the victim] couldn’t talk to me because my driver was from the clan that had accused her of sorcery

R&K: What is it like working in Papua New Guinea?

Sokhin: When you read about Port Moresby, everyone says it’s one of the most dangerous cities in the world. People talk about famous raskols, which is how the criminals call themselves, and how you can’t travel at night, you can’t use public transportation, you can’t trust taxi drivers, and all this blah blah blah. So of course, when I went there I was a bit frightened. I almost didn’t know anyone. But in reality, it isn’t that bad today. There were a lot of improvements recently. Still, you cannot walk around at night and settlement areas are dangerous even during the day. But maybe because I know the place and learned the local language, Tok Pisin, I feel confident here now. But I’m also a big huge Russian man, so that might play a part. There were some attempts on me, people tried to steal my camera a couple of times using guns and all this stuff, but I mean so far it was never very, very serious.

R&K: And precisely, as a man, how were you able to gain these women’s trust?

Sokhin: I always tried to approach women through local advocates, counsellors, or staff of NGOs, so people trusted me and my camera. There were also many situations where I could have taken pictures but didn’t, because I didn’t want anyone to think I was taking advantage of them. You understand, some of these people were in shock, so even if they said yes at the time or if they signed a consent form, it didn’t mean anything. So sometimes I had to come back. Once, I was traveling in the Highlands and there was a recent sorcery attack on a young woman. She agreed to meet me but was still hiding, so I hired a vehicle and we met in this really remote place on the side of the road. She was with her brother and when he saw my driver, he said they couldn’t talk to me because the driver was from the clan that had accused her of sorcery. So despite the long road and the heaps of money I paid to get there, I had to apologize and arranged to come back. There’s a lot of sensitive things that sometimes as a foreigner you don’t know. It’s not an easy country to work in.

There are more than 800 languages in Papua New Guinea. Of course, that’s difficult to manage

R&K: You mentioned the many types of violence against women you encountered. Are these all present in the book?

Sokhin: I put everything together to show the different angles of the violence. And there is more. There are the young girls forced to become sex workers in brothels by their families or by captors. There are maternity health issues, with the rate of infant mortality being very high. Many women die not because of a lack of medication or facilities, but because they are neglected. For example, a heavily pregnant woman could have to walk for two days to go to a health center and if she gives birth on the way and her husband isn’t with her, she can die. So I was working on different assignments with different organizations, trying to understand where this violence comes from. Another part of the book will be my personal, visual diary. I travel a lot so I write in diaries, and also I got an instant camera because people always ask me to give them photographs. I used that camera for me too and these images in my sketchbook became a part of the project themselves. It will show people who are interested what was going on in my head while I was working on this.

R&K: In the description of your project, it says that this level of violence is normally only experienced in war zones. Why do you think that is?

Sokhin: That’s a quote from Médecins Sans Frontières. They operate clinics in the country and they have victims and survivors coming in every day, lots of them. Maybe it’s because of the tribal culture. In the Highlands, people are warriors and there are tribal wars. You can see people everywhere walking with these bush knives, and in some areas, people still use bows and arrows… It’s their everyday life. So when people born in this culture of warriors come to big cities looking for a job, they bring that with them. In coastal areas, people are mostly peaceful, they’re fishermen and hunters. But the mixing creates a clash of cultures. There are more than 800 languages in Papua New Guinea, it’s a country full of diversity. Of course, that’s difficult to manage. So maybe that’s one explanation. But there are probably many, like the very fast development of the country. You know, these people lived under very different circumstances 100 years ago, but now international companies have come in, and maybe the development is just too fast. As you said though, I’m not a UN expert, so these are all explanations I’ve heard people talk about.

This country has a lot of heroes, female and male, that work in very dangerous environments

R&K: And it doesn’t help that a lot of these perpetrators aren’t brought to justice…

Sokhin: Yes, the justice system doesn’t work very well. In some areas, police are undertrained and under-resourced – and if a woman asks for help, policemen will say: “OK we’ll come to catch the perpetrator if you pay for gas.” I worked with the police, and sometimes it’s true that they spent all the amount of gasoline they received that month and so they can’t do anything. But of course, corruption is also a big thing in the country so it might also be because of that. It’s hard to say. I’m not Papua New Guinean, I’m not permanently living there, so that’s just my observation. And it’s not that everyone is violent. I met a lot of men who respect their wives, a lot of human rights defenders, women advocates working together to stop the violence, a lot of survivors speaking out and trying to change things… So I think it’s the wrong approach to blame someone, it’s better to think: what can I do to help?

R&K: What has been done so far?

Sokhin: There were many changes in the recent years. The government is working to address this issue. They recently passed the Family Protection Bill, which finally criminalizes domestic violence. They repealed the Sorcery Act, that old law that said if someone was accused of sorcery, their perpetrators won’t be prosecuted. Prime Minister Peter O’Neill apologized publicly to all the women for not doing much, so things are changing. This country has a lot of heroes, female and male, that work in very dangerous environments. They are targets of violence themselves and their families too, especially if they work with sorcery-related violence, which is a very complex issue. And there have been victims already, some activists have been killed. One was beheaded last year, because if you help victims of sorcery, people will think that you are a witch too. But despite everything, some people are doing a lot of good things. My hope is that significant changes will come. I really want to see Papua New Guinea become a violence-free country.

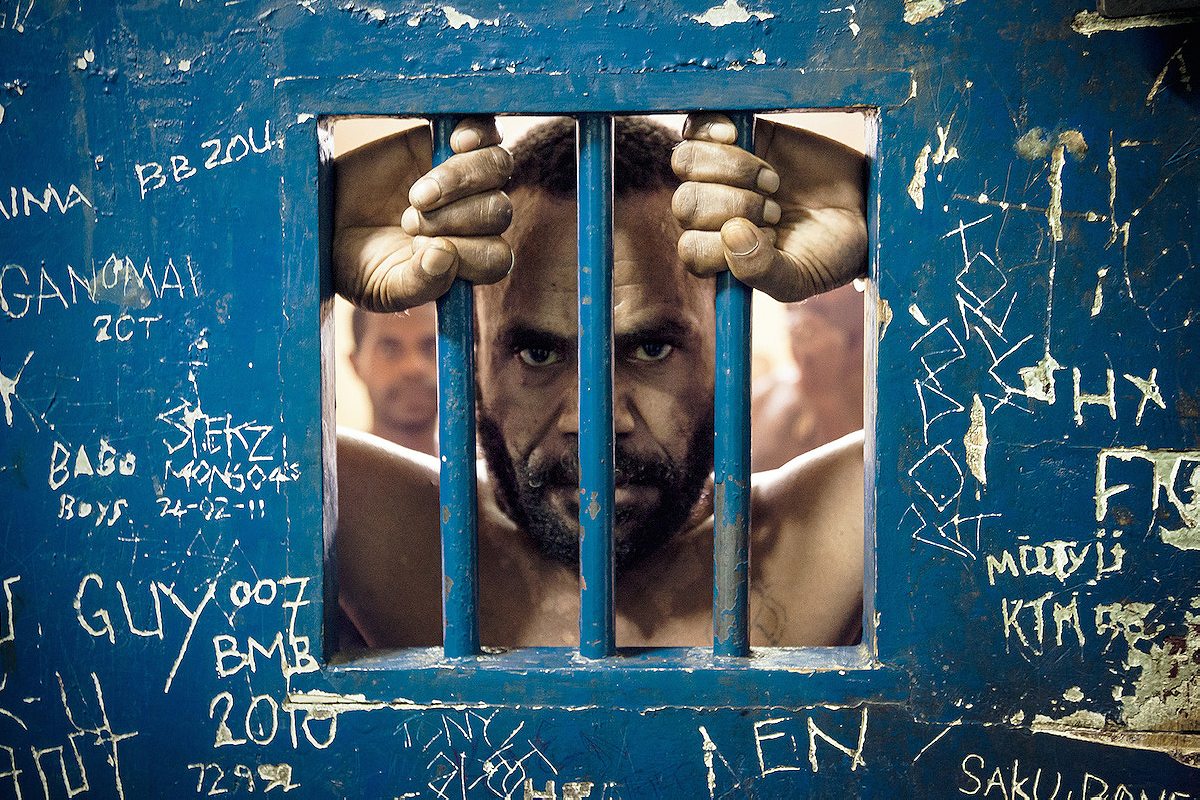

R&K: You spent time with the police and inside prisons. Why was it important to show the perpetrators?

Sokhin: I wanted to see the other side, to talk to them and understand what was in their head. I came to one prison and the policeman who was with me said: “this is a photographer, he’s looking for people who abused their wives or raped or killed a woman…” No one said anything. Then the policeman locked me in the corridor between the cells and he left. I was there alone, and all these men started saying: “take my picture, I killed my wife.” It was a bit scary being there, they were trying to touch me through the bars and grab my camera… It was an interesting situation. And as I was going from one cell to another just talking to people, collecting their stories, I was shocked to see how they talked about their crimes, they talked with a kind of bravery. Lately though, I looked at these men in another light while I was covering police brutality for the UN. These people haven’t been found guilty by a court, so they should be treated well, at least before they are found guilty. That doesn’t happen. There are so many things happening there that shouldn’t happen, so it’s the whole country whose system doesn’t work well.

You can pre-order “Crying Meri” here.