Participants in street soccer’s Homeless World Cup may not resemble the hair gelled superstars that played in Brazil last summer. But as Martin Fritz Huber discovered on the sidelines in Santiago, no home doesn’t equal no talent.

It’s the opening match of the 2014 street soccer Homeless World Cup, and Team Chile is not being a very gracious host. They’re up 13-0 against Argentina and aren’t yet finished inflicting chagrin on their neighbors to the east. The Chilean players all have compact, powerful builds, and seem ideally proportioned to excel at a game where it pays to have a low center of gravity. As they knock the ball around in front of the Argentinian goal, they look so adept at maintaining possession that the whole thing feels like a drill, or the sadistic behavior of a predator toying with its prey.

Eventually, a Chilean player drives a shot past the opposing goalie—score: 14-0—and Argentina gets the chance to go on the offensive for a few seconds. From the stands, fans cry “Chi-chi-chi, le-le-le. VIVA Chile!” When the game ends at 16-0, the crowd is on their feet, as they were when they belted out the words to La Canción National before kickoff. At the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Chile was one penalty away from knocking out Brazil, and it’s hard to imagine that that team ever received an ovation like this.

The Chilean homeless men’s squad is one of 54 teams from 42 countries who, in October, participated in the 12th annual Homeless World Cup—a street soccer tournament for those on the opposite end of the social spectrum as the hardbodied, profusely gelled celebrities who played last summer in Brazil. In order to participate here, all players must either be—or have recently been—homeless in their own country, seeking asylum in another, or earning a living as a street newspaper vendor.

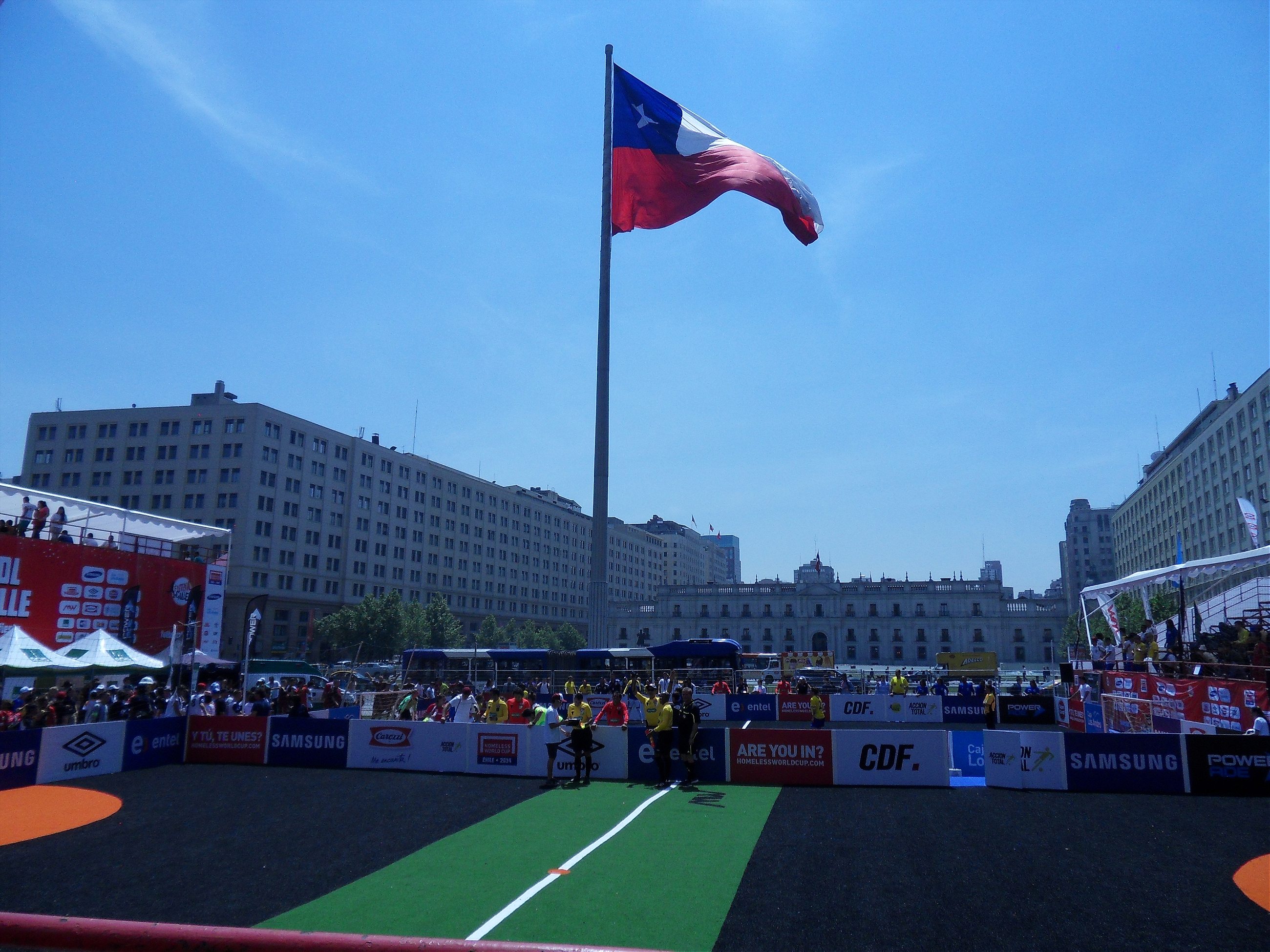

Such relative states of destitution were belied by the tournament’s regal venue in downtown Santiago, Chile: games were held on a square directly across from the Palacio de la Moneda, official residence of Her Excellency Michelle Bachelet, Chile’s president. (For perspective, one might imagine holding this event, which in years past has included uprooted souls from Afghanistan and Palestine, on the White House South Lawn.) The Homeless World Cup is no stranger to such conspicuous digs; previous iterations have taken place beneath the Eiffel Tower and on Copacabana Beach.

Locations like that don’t happen by accident, and the organization gives careful consideration to potential sites when selecting a host city—the more prominent the better. The Homeless World Cup wants you to know it exists, because that way the next time you see someone on the street who’s more than a little hard up, there’s a better chance you’ll realize that Oscar the Grouch over there could, under different circumstances, be that guy in a fly-ass uniform with thousands of spectators chanting his name.

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of perspective. That’s what inspired Mel Young and Harald Schmied, two street newspaper publishers from Scotland and Austria, to make good on a late-night, beer-fueled pact and organize the first Homeless World Cup in Graz, Austria, in 2003. That year, the tournament featured 18 teams and was a surprise hit with spectators, as it has been ever since. Today, the Homeless World Cup works with 74 partner organizations all over the world and tries to cover travel costs for all participating teams. Once the players arrive, the host country pays for everything, from staging games to supplying players with food and shelter. Amsterdam has already committed to hosting in 2015.

“I think the tournament make change the world, and do the world more better than we have now,” said Azamat Kadyrov, a 39-year-old from Kyrgyzstan, whose team had just lost 7-3 to Argentina. After the match, Azamat gifted an Argentinian player with a Kyrgyz kalpak (the traditional high-crowned felt hat worn in Central Asia) in a display of transnational camaraderie and unaffected goodwill about which FIFA can only dream. “Everybody here is one nation during this competition,” Kadyrov told me before explaining that he was a volunteer at the Street Football Federation of the Kyrgyz Republic, one of the Homeless World Cup’s international affiliates. We were joined by the Kyrgyz goalie, Ibzagimov Tuzaz (49). Azamat grabbed his teammate’s shoulder, started laughing, and said, “He homeless. Zero pesos.”

Anyone harboring doubts about the level of play at a tournament where for many participants “zero pesos” is situation normal, would change their mind after watching a team like the Netherlands, whose sinewy athletes move the ball around the 22-by-16 meter pitch with a flurry of one-touch passes, vintage Denilson step overs, and brutal volley finishes. Thanks to an unfortunate group draw, Team USA got to witness the prolific talents of the Oranje, homeless edition, first hand. The match resulted in an 11-1 defeat for the American team. (Street soccer games are three-on-three, plus goalie. Halves are seven minutes, running time.)

Shane’s story demonstrates how the system is supposed to work

“It would have been nice to have had more chance to practice,” said USA coach Johnny Figueroa, 30, a former resident of the Los Angeles-based shelter Jovenes Inc., who played in the 2008 Homeless World Cup in Melbourne and now coaches a street soccer team in L.A. “You know, some of these teams have been playing together for a year. We can’t compete with that.” Team USA didn’t have the luxury of 12 months’ worth of preparation for a tournament whose rules mandate that countries send new players every time. When they rolled into Santiago on the morning of their first game, most of the American players had barely met.

“I didn’t know anyone,” said Shane Bullock, 26, of his Homeless U.S.A. teammates. One year ago, Bullock, whose prodigious red facial hair recalls a pre-ESPN era Alexi Lalas, was homeless, jobless, and living in a San Francisco shelter. He was approached by members of Street Soccer USA, a HELP USA organization, and asked if he wanted to join their local homeless franchise, the San Francisco Change. Reluctant at first, Shane eventually became a regular at practices, which lead to a part-time job with I Play for SF, Street Soccer USA’s local network of adult soccer rec. leagues. He now lives in a single occupancy apartment.

Shane was selected to this year’s national homeless team because his story demonstrates how the system is supposed to work. Founded in 2004 by Lawrence Cann, who played Division 1 soccer for Davidson College, Street Soccer USA is a nonprofit offering a support network for marginalized individuals who might be wary of more blatant social service initiatives. Initial participation in practices is entirely voluntary, but for those who wish to officially join a Street Soccer USA Team, attendance is mandatory.

Every year, at the Street Soccer USA National Tournament, the organization announces one men and one women’s team that will represent the United States at the Homeless World Cup. Selections are based on what players have had to overcome and on whether they make good ambassadors for the organization’s let-us-help-you-help-yourself ethos. Not that playing ability is irrelevant. “We realize that the Homeless World Cup is a soccer tournament. We don’t want to be get beat 15-0 every game,” said Robert Cann, S.S. USA’s National Director. But, as one might glean from the team’s non-existent training camp, winning is not the main priority here.

Not every country is similarly agnostic about the talent of the players it sends to compete. Ryan Murray, a 23-year-old from Glasgow who’d played in Celtic FC’s youth program before “heading down the wrong path” and winding up in prison, told me that he and his seven teammates were chosen from over 1,000 players at the Street Soccer Scotland Trials back in May. (Scotland has won two Homeless World Cups.) Other powerhouse teams earned the right to represent their countries by triumphing in national street soccer competitions.

While the rules of the Homeless World Cup state that all participants must be given “a reasonable amount” of playing time, this appears subject to interpretation; Brazil, whose second-stringers showed enough futebol artistry to humiliate most early-round opponents, stuck with their starters once they reached the knockout round. (Their dramatic 8-7 semifinal loss to hosts Chile was also the only time I witnessed a lapse in sportsmanship in a tournament where the overall comportment of players was so consistently civil that it makes your average rec. league game look like the Siege of Stalingrad.)

Critics of this unabashed in-it-to-win-it approach might object that sending a semi-pro team to an all-comers event might undermine the Homeless World Cup’s reformative potential. On the other hand, it seems reasonable to assume that that reformative potential is more likely to be realized when your squad is on the right side of an 11-1 blowout. But talent disparity at the Homeless World Cup is also a reflection of how the cause and definition of homelessness in a place like Norway (whose men’s squad finished 30th overall) will be radically different than in Namibia (7th). At the risk of glossing over an incredibly complex problem, the general trend at the Homeless World Cup is that players representing affluent social welfare states are more likely to have a history of substance abuse than players coming from countries with widespread poverty. This makes for a different kind of soccer player.

“When they’re coming out of recovery, they’re never going to be necessarily the most talented footballers. That’s the way that homelessness and drug addiction structures itself in a country like, say, Switzerland,” Mel Young, the gregarious co-founder of the Homeless World Cup told me. Young, whose longish coiffure and protruding ears make him look like a mash-up of Rod Stewart and Yoda, explained that one of the central challenges of the tournament was finding a way to simultaneously accommodate the teams with novice, post-rehab players, and the teams that are overflowing with talent. Young compared his Switzerland example to “a country like Brazil where there’s so much poverty and people sitting in the category of homelessness that… the football is about the football; football is the driver out. So it’s because the definition is slightly different from country to country and the way that people use it [i.e. the Homeless World Cup] is different, it’s always a challenge for us.”

After the first few games, teams are put into groups according to skill level. Another round of play ensues before they are regrouped for the “Cup Stage,” where all teams are still competing for something, but only the best will be vying for the top prize. Such logistical maneuvering makes for thrilling late-stage matchups, like this year’s quarterfinal between Chile and the Netherlands, and helps prevent lopsided affairs like Chile’s opener against Argentina, whose roster includes an affable, fedora-wearing geriatric named Anibal.

Uniforms are hot commodities

Beyond the organizational hurdles the Homeless World Cup faces each year (e.g.: securing visas for hundreds of individuals who, as you can probably imagine, are not the folks you want waiting in front of you in the immigration line), the overriding objective of the tournament is to help demonstrate that animosity towards homeless people is ultimately a matter of perception.

Mel Young will tell anyone who cares to listen: give a homeless person a uniform and a tournament environment, and you are creating a context where, as Mel puts it, “people are cheering them, rather than walking away.” (Uniforms are hot commodities at the Homeless World Cup. I never witnessed greater jubilation than when Angela Draws, a 35-year-old, platinum-haired member of Team USA’s women’s squad scored a “Hellas” jersey from the Greek team; Ms. Draws hails from northern California, where “hella” is everyone’s favorite modifier.) When I was speaking to Sergei Newman, a 21-year-old player on Team USA who’d spent months on the streets of Portland, Oregon, begging for food money, we were interrupted by a young local woman who wanted a picture of Sergei holding her child.

About halfway though Kicking It, a documentary chronicling the 2006 Homeless World Cup in South Africa, a scene opens with a caption informing us that the “Russians are convinced that winning is the only way to focus attention on their country’s long ignored homeless problem.” Team Russia looks well suited to the task. Playing in front of the neo-Renaissance splendor of Cape Town’s City Hall, Table Mountain looming in the background, we see the men in blue and white eviscerating England’s defense. Deep in his own half, a Russian player zips the ball cross-court to his teammate, cuts a diagonal line between two opponents and, turning, receives a perfect pass before promptly slotting the ball past the England keeper.

You know you are witnessing some serious street soccer talent when you hear voiceover narration from Arkady Tyurin, Russia’s coach: “The common opinion in Russia: the homeless man must be drunk, dirty, and he has no right to play football. He has no right to be a representative of his country. And he has no right to be a winner. He must be a loser.” In the film, Arkady says that his team needs to excel in the tournament—“at least third place”—to catch the attention of the Russian media. “Maybe this is cynical,” he says, “but this is part of your life. We must win.”

Russia did win the Homeless World Cup that year, triumphing 1-0 in the final against Kazakhstan. Kicking It ends with celebrity narrator Colin Farrell telling us that, “The Russian victory was big news. For the first time, homeless people in Russia were shown in a positive light.”

Eight years after Cape Town, however, Arkady Tyurin appears to have given up on the Russian media, whom he now refuses to speak to on account of their continued “hate speech towards socially excluded people.” Arkady, who was wearing rolled up jeans and red Converse All Stars when I spoke to him in Santiago, told me “nothing changed” after the victory in Cape Town. “We play for ourselves,” he said, “We are not dependent on the common opinion.”

I asked him if participation in the Homeless World Cup had improved the lives of his players, many of whom had long struggled with addiction and lived in remote areas of a country where remote really means remote. (Russia has its own national homeless soccer tournament, where it selects its team. This year, the tournament was held in Berdsk, Siberia, over 2,000 miles east of Moscow.) Arkady said that he had no doubt about the impact of the tournament on his players. He said that he had seen, again and again, how the “responsibility of team play” had turned “boys into men.” This transformation reminded him of another filial aspect of his long-time stewardship of homeless soccer in Russia. He told me that many of his former players, with whom he’d kept in touch over the years, were having children. “Those children, when they are born, they have a silver spoon from me,” he said.

If the boys on Arkady’s team (who looked to be in their 20s and 30s) do become men through their experience at the Homeless World Cup, their ability to flourish in this newfound manhood will greatly depend on the opportunities available to them when they return. There is such a strong “We’re all in this together” vibe during the Homeless World Cup that it’s easy to forget that for a player like Camilla Lindén (40), a recovering addict from Gothenburg, and Shweta Shetty (18), an orphan who grew up in a Pune shelter, the edifying effect of the tournament is going to play out somewhat differently.

In its early years, the Homeless World Cup solicited player feedback in the form of a survey, which participants took six months after returning home from the competition. Each year, over 90 percent of those polled claimed to have found a “New Motivation for Life.” But how long is that new motivation likely to endure when your homelessness is a direct consequence of endemic poverty or perpetual war?

You don’t have to be the most limber of mental gymnasts to see how the latter two circumstances might apply to several players on Mexico’s homeless team, who grew up in rough neighborhoods in Tijuana and Juarez during years when drug-related violence was at its peak.

“Sure, some of our players were involved in illegal activities,” Daniel Copto, president of Street Soccer Mexico, told me. Copto, 64, speaks fluent English after spending 11 years working as an addiction counselor in Toronto. He coached the 2005 Canadian homeless soccer team, and decided that his native country could benefit from a street soccer league of its own. “I wanted to do something for my country and this was it,” Copto said. He moved back to Mexico for the explicit purpose of starting Street Soccer Mexico, which he says began “informally” in 2006—the year Mexico first sent a team to the Homeless World Cup—and officially in 2008.

It was tough going at first. Lacking sufficient funds to keep the program running, Copto said he was about to give up when, in 2009, a friend arranged a meeting with a representative from Fundación Telmex, a philanthropic offshoot of the Carlos Slim (a.k.a. the “Mexican Warren Buffet”) empire. Impressed by the idea, Fundación Telmex donated $150,000 to finance pilot programs in eight Mexican states the first year. Today, they remain the organization’s sole sponsor.

With Telmex’s continued backing, Street Soccer Mexico now has leagues in all 31 Mexican states, and in the federal district of Mexico City. Last year, membership was at 26,600. There is no requirement to join (i.e. you don’t need to be homeless) and Copto believes that one of the organization’s key benefits is that it facilitates interaction between social classes in a very segregated country.

Mexico’s annual Homeless World Cup roster is selected at the national championship, which invites the top homeless teams from state-level leagues. The eight men and eight women who are given the nod attend a three-week training camp at what Copto describes as an “Olympic” caliber training facility (gracias, Telmex), where days are filled with rigorous practice, group and individual counseling, and doses of Hollywood pathos. (Maybe Pay it Forward is less hokey in Spanish.)

Most crucially, Street Soccer Mexico’s benevolent intervention doesn’t end with the Homeless World Cup. Starting this year, all players will have a quasi job opportunity when they return, in the form of material support to start their own hyper-local street soccer leagues. The hope is that this will establish street soccer programs where they are needed most¬ and that the players creating them will spread the euphoria of their Homeless World Cup experience, like reverse missionaries, back from the Promised Land.

Towards the end of the week, I was sitting at café just off the tournament grounds with Pasi Nurmela, 39, a player on the Finnish team who had some down time before his team played Italy later that evening. The weather had been warm all week and we were sitting outside, facing a large public housing complex whose façade bore grey, spackled bullet holes from the coup of ’73.

Pasi told me he spent many years in prison on drug-related charges, but since coming out had found some equilibrium through the help of local Narcotics Anonymous chapter, and a street soccer team called the “Stray Dogs.” They practiced three times a week. “Football,” Pasi said, had given him “better friends.”

I asked him what the best part of the Homeless World Cup had been. He said it was meeting new people. At first I thought Pasi meant other players in the competition, but soon I realized that he was also talking about the local population, los Chilenos. In Chile, Pasi said, attitudes towards the homeless felt less judgmental than back home in Finland.

“You see that you are okay,” he said. “Not the same guy you were before.”