Merge Records started in a bedroom in Chapel Hill 25 years ago. Today, they are one of the most influential indie record labels in the world.

“Matt, this is Mac.”

“Hey.”

“Yeah, Mac, Andrea’s husband. What are you up to?”

“Umm, not much. Just having drinks with friends. “

“Cool. Well, I just got done playing and was looking to grab something to eat.”

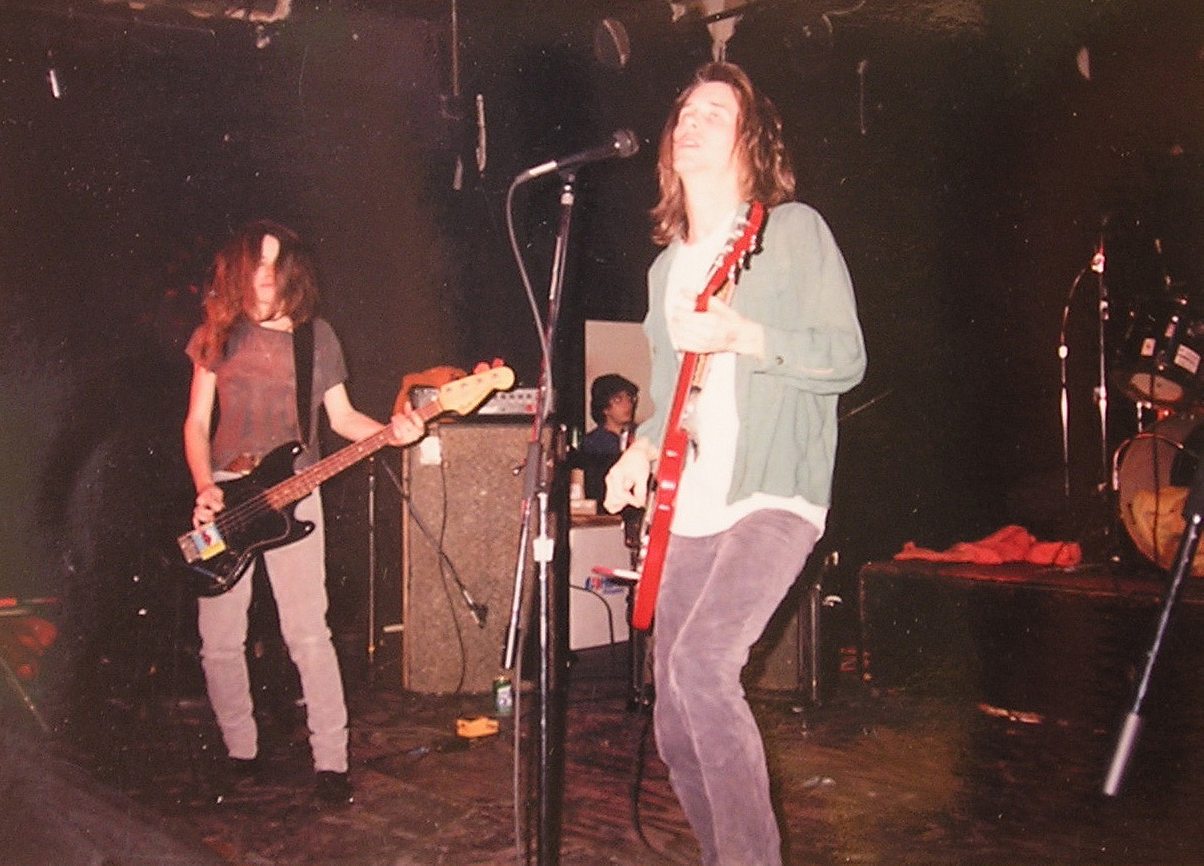

That is how I met Mac McCaughan for the first time at 12:30 am on Sunday morning on the corner of Ludlow and Rivington on New York’s Lower East Side. He had just finished playing Bowery Ballroom with his band Superchunk and he was hungry. “Maybe some pasta and a glass of wine,” he said over the phone.

At that hour on the Lower East Side, the packs of young boozehounds and Jersey castaways can take on a menacing shape, but Mac cut a sharp figure through the heaving mass: dark sweater, dark jeans, the crispy collar of a checkered button-up peeking out of his top. Hair standing at full attention.

We went to ‘inoteca, a buzzy wine bar filled with popped collars and salty little snacks. We ate sheep’s milk cheeses and drank the juice of obscure Italian grapes and talked about Obama’s first two years in office, our favorite restaurants in North Carolina, Mac’s two decades as a pescatarian. For the better part of two hours, I tried to figure just why, exactly, he had called me—feeling equal parts confusion and self-consciousness about receiving a call from the lead singer of a popular punk band in New York on a Saturday night.

At 2:30, when Mac disappeared into a cab and I wandered my way down Ludlow, looking for another drink, I remember thinking: “So that’s what it’s like to party with a rock star?”

1987 was the year when it all happened for Mac. That was the year that he decided to take a break from studying at Columbia University, to spend the time instead in Chapel Hill, three McDonalds away from where he grew up in Durham, trying to insert himself into the slow-simmering local music scene.

That was the year that he began to form bands like most 19-year-olds form thoughts. He and a crew of local musicians decided to press a set of 7” records from five locals bands almost nobody had ever heard of.

He convinced Laura to take up the bass, to be a part of his band, and to leave her boyfriend

And that was the year that Mac met Laura Ballance. They worked together at Pepper’s Pizza in Chapel Hill, making pies for the Tarheel student body. As anyone who knows him will tell you, Mac can be very persuasive when he wants something. In the summer of 1987, he wanted two things: to make music and to be with Laura, and being the enterprising young man that he was, he thought it would be better to have them together. He convinced her to take up the bass, to be a part of his ragtag punk band, and to leave her boyfriend, back then the king of Raleigh’s hardcore scene. Laura was beautiful and mysterious, the infatuation of young punkers across the Triangle, but she had never touched a guitar.

“It’s one thing about Mac and I don’t know if it’s a good thing or a bad thing, he’s willing to go through with things even though they’re half-assed,” says Laura. “There’s me up on stage who can’t play an instrument, fucking up constantly, terrified. He’s like ‘We’re doing it! No one else can tell!’ That’s just the way he is, always shooting for the moon.”

Out of these unlikely puzzle pieces emerged two fixtures of indie rock that today, on the eve of their 25th anniversaries, live on as a testament to extemporaneity, persistence, and the occasional moonshot: Superchunk, the hard-rocking quartet that helped define the punk-pop genre that come into full bloom in the 90s and early 2000s, and Merge Records, one of the most influential and successful independent record labels in America. It’s impossible to tell the story of one without the other.

Superchunk took many names and shapes before it became Superchunk: Slushpuppies, Quit Shovin’, Metal Pitcher, Chunk. They played at house parties and tiny Chapel Hill venues, Laura too petrified to look up from her bass strings, Mac too in love with making music to realize theirs wasn’t any good. But they played on, changing names and styles and bandmates frequently, sometimes painfully, over the next few years, until the Superchunk of today was set: Laura on bass, Mac on vocals, Jon Wurster on drums, and Jim Wilbur on lead guitar.

In 1989, a cross-country road trip—one punctuated by an engine fire in New Mexico that burned Mac’s father’s van to the ground—brought Mac and Laura to the offices of SubPop in Seattle. Back then, SubPop was a young label putting out 7” for Mudhoney and Fugazi, but they were destined to be the pioneers of a new age of rock. On the long road back to North Carolina, Mac and Laura decided that there was no reason they couldn’t do the same. As they sat contemplating the records they would make and the tours they would organize, Laura quietly read the road signs flashing by and they had a name for their little record label.

In 1991, SubPop released Nirvana’s Nevermind and the entire music industry fell to its knees trembling. It wasn’t just the fact that the album sold a billion copies, it was the fact a group of cardigan-clad longhairs who looked like they had been cast for a zombie apocalypse flick could so easily persuade suburban parents to part with $10. Alternative rock had a name and a face, and soon, every A&R in the country was scrambling to find the next big act, throwing briefcases of money at any disaffected grunger who could play a chord or hold a tune. Like every bubble before and since it, the indie rock explosion was fueled by equal parts hope, fear, and delusion.

‘The next Nirvana’ hung from their necks like a Fender electric

Superchunk was—quickly, inevitably—wrapped up in the fervor. “The next Nirvana” hung from their necks like a Fender electric. Maybe they didn’t look the part, but their noisy, catchy, caffeinated jams had gotten the attention of record people around the country. “Slack Motherfucker”, written about Mac’s discontent for a lazy coworker at Kinkos (“I’m working, but I’m not working for you!”), could have been the angst-driven anthem for a generation of young misfits.

Between Superchunk’s early success and the laidback, liberal attitude of a college town, it wasn’t long before certain people—the New York Times among them—christened Chapel Hill “the next Seattle”.

Entertainment Weekly dedicated a 1993 article to the theme, claiming Seattle had grown passé and that Chapel Hill was the logical replacement, all the while questioning if Superchunk even had the desire to take up the mantel:

Superchunk’s McCaughan currently has it made: a steady part-time job in a record store and the adulation of the locals. And the band rehearses in a farmhouse in the country where they can practice without bothering anyone. Why would they want to sign with a major label and get treated like just another alternative-rock band?

“We had enough perspective to recognize the media hype,” says Laura. “Just because they say something doesn’t make it true. If it worked out that we were the next Nirvana, great, but we knew we weren’t.”

The glare of the music industry fell on the Triangle like the eye of Sauron

Unlike hundreds of other bands that cashed in on the sudden spending spree, Superchunk resisted the steady stream of major label interest that followed them throughout the early 90s, opting to make their own music and build out the Merge label. The glare of the music industry fell on the Triangle like the eye of Sauron nevertheless.

It was a good environment to be making music in, says Laura, “the perfect combo of good record stores, three great college radio stations supportive of indie music, a lot of great venues, and cheap rent.”

But North Carolina didn’t have Sonic Youth, Pearl Jam and Nirvana; it had Angels of Epistemology, Archers of Loaf and Superchunk. “Chapel Hill was the next Chapel Hill,” she says.

It was in this breathless moment of indie rock’s rising that my parents decided to pack up our lives in California and U-Haul them 2,600 miles east on Highway 40 to North Carolina. They chose the Triangle because Fortune had named it the Best Place in America to Raise Your Family, an algorithmic expression of the area’s low crime rate, high education levels, and all the trappings of a polished suburban existence. It was the south, but without the capital S. Biscuits and barbecue and Baptism, but with three top-tier universities and a steady stream of transplants to cut through all the carbs. (Our town, Cary, earned the nickname Community of Arrogant Relocating Yankees around the same time we touched down.)

The early 90s was a fine time to be a young music lover

As a young skate rat with little to do but wax curbs and blast music, I was vaguely aware that this new home came with its own local soundtrack. Fugazi, Minor Threat, and Black Flag were the soundtrack for one faction of semi-rebellious youth, Wu Tang and Gang Starr the chorus for the other. I fell mostly into the latter camp, but like Mac a decade before me, I found my way into the Cat’s Cradle on Franklin Street to see a few of the groups that represented the new Chapel Hill: Archers of Loaf, Polvo, bands, from the looks of it at the time, that held no ambitions beyond the next set. Regardless of what your jam was, the early 90s was a fine time to be a young music lover, and though we didn’t know it at the time, it was us—the skaters, the stoners, the teenage suburban misfits—who were financing the revolution.

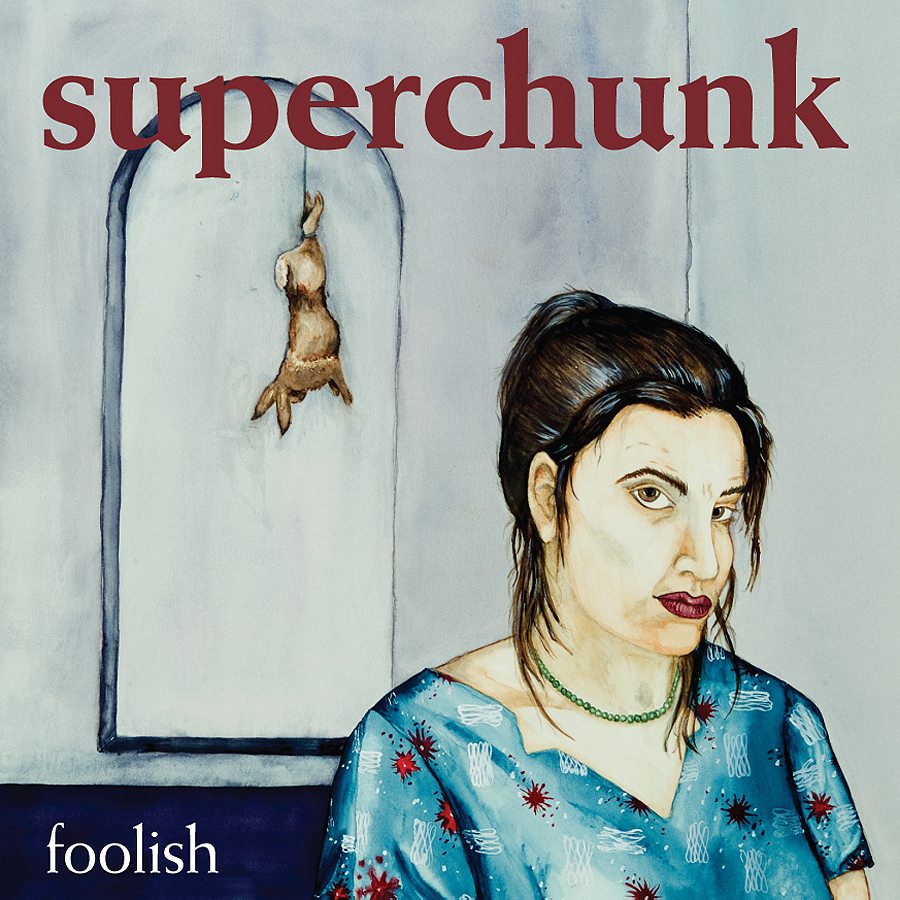

In 1993, Mac and Laura broke up. Soon after, Superchunk released Foolish, its fourth full-length album, and punk devotees dissected the work like a murder scene, dusting every lyric for heartbreak, combing the liner notes for signs of Superchunk’s future.

Though some of those signs were far from subtle—the heart-wrenching lyrics of Driveway to Driveway, the self-portrait Laura painted for the cover art with a dead rabbit dangling behind her—Mac maintained the album had nothing to do with the personal turmoil threatening Superchunk.

Amazingly enough, the band kept playing. This didn’t prove easy. As Laura wrote in Our Noise, an essential history of Merge Records co-authored with Mac and John Cook, “I asked for Mac’s vocals to be taken out of my monitor mix. Because the words were making me cry. I would be on stage, playing these songs, and I would be crying.” This was Sad Superchunk, but also Big Superchunk, playing the main stage at Lollapalooza, garnering favorable reviews in all the big music pubs, and underwriting a fledgling label.

Here’s Where the Strings Come In, the 1995 follow-up to Foolish, sold 37,000 copies, making it the best-selling album of Superchunk’s career. They spent the rest of the 90s keeping up their furious pace of production, releasing two more albums—Indoor Living in ‘97, Come Pick Me Up in ‘99—and playing each new set of songs to crowds the world over. Despite the rush, they never feel into anything resembling rock star behavior: no groupie sex, no drugs, minimal drinking.

Superchunk never made it out of your cool buddy’s Walkman

“We were the most unglamorous bunch of nerds out there, but we never failed to back the van up to the club and unload a rock show,” says Jim Wilbur, Superchunk’s lead guitarist.

They were constantly moving, but the band’s trajectory leveled off in the mid 90s, just as the entire music industry began to shift in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s suicide. Despite the albums, the tours, the pronouncements from tastemakers across the industry, Superchunk never fully broke through. They never made it out of your cool buddy’s Walkman.

Nobody from Superchunk ever seemed that surprised. They would have loved a bigger audience, but they weren’t about to change their to facilitate. “You listen to our records and they’re all pretty scrappy sounding,” says Mac. “Pretty punky. A little bit weird. My voice…well…I was never going to sing like Eddie Vedder or the guy from Stone Temple Pilots.”

For years they remained a group permanently on the tips of people’s tongues, but rarely on their lips.

For three days every May, Barcelona transforms into the center of the indie rock world. The Catalan capital has hosted Primavera Sound for 16 years, shepherding it from a small showcase of mostly local bands and DJs to a 200,000-person Mediterranean moshpit. Though Primavera pulls in top talent from all corners of the rock world, the festival this year could be mistaken for a Merge biography.

There is Neutral Milk Hotel, the enigmatic Louisiana fuzz-folk outfit, whose 1998 In An Aeroplane Over the Sea, a luminous, painful, feverish reinterpretation of The Diary of Anne Frank, remains among the most influential artifacts of the 90s indie landscape. It was also Merge’s first genuine hit, proof to the music world that Mac and Laura weren’t running a local label, but a real player in the indie space.

The band has only played in public a handful of times since they dissolved in the wake of Aeroplane’s massive success, and the crowd shuffles nervously as they wait for the band to take the stage. Most seem chiefly concerned with verifying reclusive frontman Jeff Mangum’s existence. He comes out alone, rocking a Van Winkle beard and a trucker hat pulled over his eyes. He strums his guitar twice and starts in: When you were young you were the king of carrot flowers…

There is Spoon, the band that by most measures shouldn’t be here today. Before Merge, they put out two unsuccessful albums—one for indie-trying-to-be-major Matador, another for major-trying-to-be-indie Elektra—that sold less than 10,000 copies combined. Nobody would touch their third album after Elektra dumped them, but Mac and Laura took a chance anyway. Thirteen years and hundreds of thousands of records later, they’ve become an enduring staple of the American rock scene, beloved by hipsters and frat bros in equal measures. Now, in Barcelona, as the sun disappears into the Catalan countryside, casting a wild orange glaze over the Mediterranean, they play for a pack of thousands on the venue’s largest stage like they were born to be here.

There is Arcade Fire, the juggernaut, the envy of every record label in the world. When Win Butler sent a demo to Chapel Hill in 2004, he and Régine Chassagne and a rotating cast were still playing bars in Montreal for crowds scarcely larger than the band itself. For months they didn’t hear back from Merge. Butler and Chassagne grew impatient, decided to sign with a small Montreal label, but just before the deal closed, Mac and Laura called and convinced them otherwise. Funeral went on to sell 400,000 copies. The Suburbs won the 2011 Grammy for Best Album, the first in Merge history. Reflektor, a dense and sprawling and ambitious album, debuted at #1 on Billboard last year.

Turning 30,000 people into a single voice that rattles all of Barcelona until the night feels like it’s about to give out

An hour before they’re scheduled to play a mass of Brits and French and Catalans forms 20 rows deep around the Sony Stage and things grow testy in ways not normally seen at a festival dominated by Spanish sun and Moroccan hashish. When the band finally takes the stage, clad in sparkly suits and bathed in black lights, they play like they’re the last rock stars on earth: switching instruments during songs like a game of musical chairs, blasting cannons that cascade the crowd with confetti, turning 30,000 people into a single voice that rattles all of Barcelona until the night feels like it’s about to give out.

And there is Superchunk, the metronome of Merge, your favorite band’s favorite band. After a 7-year hiatus, they released Majesty Shredding in 2010, followed by I Hate Music in late 2013—an album that is about, among other things, getting old. They may no longer command sustained attention from record executives and rock writers, but they draw a steady sunset crowd at the ATP stage, and nothing about the performance suggests the band has lost its edge. Mac, in particular, plays with a burning urgency; he windmills and scissor kicks and sweats and squelches his way through a 50-minute compendium of Superchunk’s greatest hits. The Spanish girls next to me, 4 years old the first time the band played Europe, wonder aloud if the moment merits an Instagram post.

After the show, I meet Mac at his hotel. I’ve promised him a tapas crawl through the city, starting with Tickets, Albert Adria’s small plates pleasure palace on Avinguda del Paral.lel. But this is Barcelona, land of 50 percent youth unemployment, where coastal rock shows and tapas wonderlands come with a side of civil unrest, and tonight that unrest has fermented into a smoldering mass that has paralyzed large swaths of the city. Suddenly, hundreds of hooded protesters lie between us and spherified olives and truffle air. We implore our taxi driver to bravely push on, but he sees the fire and beats a fast retreat.

“There’s no way you’re getting to Tickets tonight.”

This is Barcelona, where rock shows and tapas wonderlands come with a side of civil unrest

As we speed past the port, back towards a less-agitated part of Barcelona, Mac snaps iPhone photos of the plumes of smoke rising above the Columbus statue at the foot of the Rambla.

We end up in the Mercat del Born, a 300-year-old market complete with its own sprawling tapas emporium, planted in the center of the city’s slickest neighborhood. We order Catalan tomato bread and anchovies and a mound of salt cod braised into soft white ribbons.

“I love Spain,” says Mac, a Catalan pilsner raised to his lips. “When everyone else across Europe was doing the electronic thing, Spain was still supporting punk.”

No small part of the Spanish amor comes down to Primavera. “It’s hard to think of a better festival. What’s so cool about Primavera is that the venue is actually in Barcelona. It’s not some field in the middle of nowhere Tennessee.”

Superchunk has seen much of the world from the window of a tour van. Mac in particular, whose wife Andrea Reusing is the chef at Lantern, one of the Triangle’s best restaurants, sees the world through food. “Did you make it to that crazy kaiseki place in Kyoto?” he asks when he hears I just came back from Japan. “How about Sawada in Tokyo? Best sushi in the world.”

But any band with Superchunk’s mileage has more than a few horror stories to tell from the road. The time when their van broke down in France and they slept in a field using newspapers as blankets. The racist owner of a Virginia Beach club who addressed Mac with his pistol on the table. And the hurricane force winds in Copenhagen that left the band with just 20 Danes to play for.

Understandably, Mac’s enthusiasm (“yeah, but those were the best 20 Superchunk fans in Denmark!”) isn’t always shared by the whole band. But Wilbur says it’s the monotony, not the disasters, that drags a tour down. “The true reason touring can suck is that for the most part it is deadly boring. Endless drives, traffic, airport lines, lousy toilets, hours of waiting around, sleep deprivation, hearing the same voices everyday.”

Mac admits the threshold for going on the road has changed. “Laura’s not touring right now [because of a hearing condition], Jon doesn’t love to tour. I have kids at home.” But it’s more than just the displacement; it’s trying to make new inroads in a place you’ve been coming to for years. “It’s weird coming out now and having to basically introduce yourself to a new crowd,” he says. “Most of the younger people have no idea we’ve been doing this for 25 years.”

***

For the first three years, Merge Records lived out of Laura’s bedroom. Back then every facet of the label—cutting out mailers from cardboard, stuffing singles by hand, cold-calling distributors to see if they’d take some records—came soaked in the DIY ethos that propelled the punk movement of the 80s and 90s.

“We would borrow a couple hundred dollars to press records, then pay family and friends back when we sold them,” says Mac. That’s how the first 10 7” were made.”

It was 10 years before Laura and I took our first checks

You might say that Merge was built on a stack of 7” vinyl, the medium of choice during the early 90s boom of garage bands. It was the only economically viable way for a small operation to put out music without a huge investment. Mac wrote passionately about the importance of what he called “the people’s medium” in his liner notes to 1991’s Tossing Seeds, a collection of Superchunk singles.

It is about the conceptual greatness of the 7” single: What can you do in three-and-a-half minutes that will make us get up and put the needle in the groove time in again? The single must be a distillation of one’s powers, the most exciting slice of noise a person can cram between the lip of the disc and the edge” of the label.

While Mac and Laura proved successful at selling music three-and-a-half minutes at a time, their transition from slingers of singles to a real record label came with a learning curve. In a handful of early releases, they forgot to hold back money for reserves, unsold records returned by the distributor, forcing them into the red at critical moments for a tiny label. Later, they were issued a Cease and Desist from the Jehovah’s Witnesses for using a scene from their literature as cover art. And their no-contracts policy turned sour when they lost And You Will Know Us By the Trail of Dead to Interscope just before the release of Source Tags and Codes, an album that sold well and garnered a perfect 10 rating from Pitchfork.

Money in those early years trickled in slowly. “It was 10 years before Laura and I took our first checks,” says Mac. Though other Merge bands achieved critical success, it was Superchunk that paid the bills for many years.

Despite those early hiccups, they turned out to be extremely effective at running a label. They signed bands only after methodical consideration and offered smaller advances in exchange for larger royalties on the back end. To defray upfront cost and overall risk, they partnered with Touch and Go, an independent label based in Chicago, to handle the production and distribution of all Merge albums—a partnership that would last for the better part of two decades.

Mac and Laura may have fizzled as a couple, but they complemented each other well as business partners. Mac was the one with crazy creative energy, the parent you go to when you want a yes, Laura the savvy, conservative voice of reason with her eye on every penny. There were no specific goals, no benchmarks, no discussions of long-term business plans: just a slow, steady climb to the top of the indie world.

Today Merge Records is housed in a two-story brick building in downtown Durham. Back when Merge finally moved out of its series of makeshift offices and into a permanent home, this was a rough stretch of street in a city known for making trouble. Today, there’s a low-lit French bistro, a members-only speakeasy, a Southern-inflected tapas bar, and a highbrow sandwich spot called Toast all within walking distance from the offices.

The Triangle has changed a lot since the Merge bedroom years. Jesse Helms died. Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s moved in. Asian and Mexican immigrants joined the flood of New York and California transplants in the area, reshaping the taste and face of communities across Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill. The state turned blue in 2008 for the first presidential election since Gerald Ford, though the fierce red rebuttal—one that included slashing unemployment benefits and creating the most restrictive voter ID laws in the US—over the past two years makes liberals like Mac and Laura wonder if it was all just a dream.

More than ever, this is an area with two identities: Budweiser and craft Belgians; Priuses and pickup trucks; Sacred Sundays and Moral Mondays; small music and Big Tobacco. In the Triangle, the American Dream has never been more open to interpretation.

Merge may have cast off the perception of being a regional label long ago, but North Carolina is still very much in its DNA. Yes, the employees are from the Triangle and many of the bands are still local, but it’s the overall vibe of Merge that feels so Carolinian: the office doesn’t buzz, it gently purrs. Merge is serious without ever taking itself too seriously.

Mac’s office looks exactly like what you’d expect an office of an indie record exec to look like: shelves covered in Japanese action figures and Merge merch, his desk a breeding ground for unplayed CDs and old demo cassettes. He doesn’t look especially at home at said desk, as if that innocent dream to run a record label all those years ago never included a computer and a 401K.

In the heady Nirvana years, independent labels multiplied like fungus. While some were built on the purest of intentions, many of these new boutique labels had no business putting out records, and stories of artists being burned by the smalls were nearly as common as artists being burned by the bigs.

Merge’s longevity is rare. “In indie rock years, McCaughan’s approximately 100,” reads a 2005 Pitchfork review of Portastatic, a side band Mac started in the 90s. In the fickle world of music making, Merge endured because they never forgot who they were. No lavish steak dinners to woo a young band, no outlandish advances to bring in a proven talent. In many functional ways, the company is still run like it was back when Laura and Mac were stuffing 7” singles by hand.

“Anytime we do something out of character, like offer a big advance, it never goes well,” says Mac. Which is why their signing process remains essentially unchanged 25 years later: Mac listens to something. If he likes it, he passes it on to Laura. If she likes it, they set it aside for a while. If they come back to it, then it’s a winner. No sales charts, no projection models. When Billboard magazine asked Mac about how he feels about “research-based A&R”, he said: “I don’t even know that is.”

The music industry has changed dramatically since the Seattle years. It’s moved from vinyl to cassette, cassette to CD, CD to iTunes, iTunes to Spotify and a dozen other streaming services that pay pennies to labels for the right to pillage their entire catalogs. Along the way, record sales have declined 63 percent since 2000, according to Nielsen SoundScan.

“Consumers don’t have a sense of it,” says Mac. “They just see all the great bands. ‘I can just listen to this stuff all day for free.’ For them it’s great until it doesn’t exist anymore.”

Merge puts their bands on Spotify, but talking to Mac, you get the sense that it’s not because they want to.

“We kept I Hate Music off of Spotify for a few weeks to see if it would affect sales. People on Twitter were like “when’s it going to be on Spotify?” Luckily someone chimed in and said, “Why don’t you spend $9.99 for the album?”

And yet, Merge has never been more successful than on its 25th birthday. If there’s something good to be said about the current State of Rock, it’s that format changes, advances in the distribution channels, and the rise of music blogs have leveled the playing field. The difference between the power of a major and an independent label grows ever slimmer, which is why many top-tier artists have been going small in recent years. That’s just one toe of the Merge footprint.

Neutral Milk Hotel’s Jeff Mangum, in an email sent to Mac during the writing of Our Noise, said what a thousand other artists are no doubt thinking today:

“It gladdens me that it’s the human labels like Merge who are fully alive in this moment, while the giants of the music industry are all eating shit. May it forever be so.”

‘We’re all in this together. That’s the most punk rock thing to me.’

The human aspect is something that everyone from Arcade Fire to The Clientele to M. Ward cite as a central reason for them wanting to be Merge bands.

“We’re all in this together,” says Laura. “That’s the most punk rock thing to me. Nobody is above anyone else. We don’t have the upper hand.”

“There’s a shared ethos that is palpable I think for artists and for fans,” says Dan Snaith aka Caribou, the Canadian electro composer and one of Merge’s bestselling artists. “I’ve always thought that if the music itself comes first everything else will fall into place. That seems like a reasonably good synopsis of Merge’s 25 year history.”

For all the speculation about the key to Merge’s success, there’s one factor that doesn’t get discussed enough: that in an industry fueled almost entirely by speculation, Mac and Laura and their stable of employees have the closest thing to infallible taste. Comb through the Merge catalog and you’ll struggle to find a bad record. From the melancholy musings of East River Pipe’s We Lived in Rented Rooms to the brash, blownout licks of Archers of Loaf’s Icky Mettle to the genre-defying scope and raw ambition of Magnetic Fields 69 Love Songs, few if any labels have made such consistently transcendent music in the modern era as Merge.

Maybe that’s why when I ask Mac for the quintessential Merge band, he doesn’t say a record-selling juggernaut like Arcade Fire or Spoon, and he doesn’t reach for an avante-garde pioneer like Neutral Milk Hotel or Magnetic Fields. No, for Mac, the quintessential Merge band remains Lambchop, a shapeshifting Tennessee ensemble that describes itself as ““Nashville’s most fucked-up country band”.

Quintessential? I ask both Mac and lead singer Kurt Wagner why, and they both offer perfectly reasonable answers.

Wagner: In the same sensible, modest way that Merge continued on all these years, we try not to bite off more than we can chew and live within our means.

Mac: It’s a group that inspires us as a label. Every time they make a record, we’re so excited to hear it.

But that’s not the whole story. There must be more in the genetic code of the quintessential Merge band.

Maybe it’s because Lambchop is a bootstrap band, formed on a whim, without objectives or expectations—just a desire to make weird and beautiful music with a group of friends.

Maybe it’s the fruit basket. The one Wagner left on stage during a Nashville Superchunk concert as a way of introducing himself. Mac picked up a banana, lamented its state of under-ripeness to the confused crowd, then proceeded to slip on the peel and fall on his back in the middle of his set. Wagner’s reward for the fiasco wasn’t a lawsuit, but a contract and an 21-year business partnership.

Or maybe it’s because after 12 releases, countless frustrating tours, and nearly two decades spent wondering why Lambchop never fully broke through to an American crowd, Mac still talks about them like they’re the hottest new band on the label. When the name comes up in his office, he sits straight up at his desk, eyes bright, hands air-punctuating his sentences. “I mean, these guys are so good!”

Later, when I tell Wagner about Mac’s reaction in the Merge offices, I can hear him choking up over the phone.

“I don’t think they’ll ever give up.”

[Header image by Matt Goulding]