The immigrants of Prudentópolis are doing their part to keep the culture of (independent) Ukraine alive.

The first signs of Prudentópolis, after miles of pine and Araucaria forests and wheat fields under the blue and cloudless sky, are the Byzantine domes of its churches. Then, after crossing into the city proper, the names on the storefronts—Klosowksi, Zubreski, Bohaczuk, Techy—offer final confirmation: you have reached the heart of Ukrainian Brazil.

As the notion of what it means to be Ukrainian is tested on the battlefields of Eastern Ukraine, there is little doubt in Prudentópolis. These are Ukrainian patriots: originally from the province of Galicia in what is now western Ukraine, they believe, as western Ukrainians still do, in the sovereignty and unity of that country. To that end they have raised money—$1000 recently for hospitals and refugees, more coming soon—and tried to raise awareness of the Ukrainian cause. Although, in Prudentópolis, few need reminding. Even for Brazil, a country of immigration clusters, Prudentópolis is remarkably concentrated. Around seventy percent of the population of 50,000 inhabitants are the descendants of Ukrainian immigrants who arrived in the nineteenth century.

Located in south-central state of Paraná, about 200 km from Curitiba, the city does not lack for nicknames. “The Vatican” for its vast number of chapels and churches. “Honey Capital” because, well, they make a lot of honey (same explanation goes for “Black Bean Capital”). They have recently pinned their economic hopes on a different nickname—“City of Giant Waterfalls”—because there are more than 100 waterfalls in the area, some as high as 200 feet, and they want to draw tourists in to see them. “The numbers are still modest, but the adventure tourism is developing fast in the region”, says Johan Schipper, manager of the Department of Tourism. There are in fact backpackers and pickup trucks and 4×4 jeeps roaming the streets, but one can’t help but feel that the off-road set is somehow in direct opposition to the real challenge facing this place: how to preserve the unique agricultural heritage and identity of its Ukrainian community.

The first large waves of newcomers arrived from Galicia, which back then was the eastern end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They were mostly illiterate peasants who were, by many accounts, lured by the agents of shipping companies selling passage to the Americas. Brazil and Canada had an open-door policy to European immigrants, largely to populate strategic lands along their borders and in virgin forests. But the shipping companies took this further: agents spread word of “lands without lords” the “roads made of emeralds”. The reality did not match: Iosef Oleskiv, an Lviv intellectual who came to Brazil in 1895 to investigate the conditions for migrants later wrote: “if someone asked me to describe in one word what Brazil means for our migrants, that word would be: tomb.” Oleskiv convinced many to give up or opt for Canada, but many others never got the message.

Their destination was Paraná, where they were to help consolidate Brazil’s occupation of the territory and grow food to supply the region. But they arrived to a land of broken promises: no infrastructure, no demarcated land lots even. Prudentópolis was then just a street of mud with a single telegraph line, entirely surrounded by a large pine forest. The government withheld provisions as a way of forcing newcomers to cleanse the forest and start planting, but this led to extreme hunger and even death.

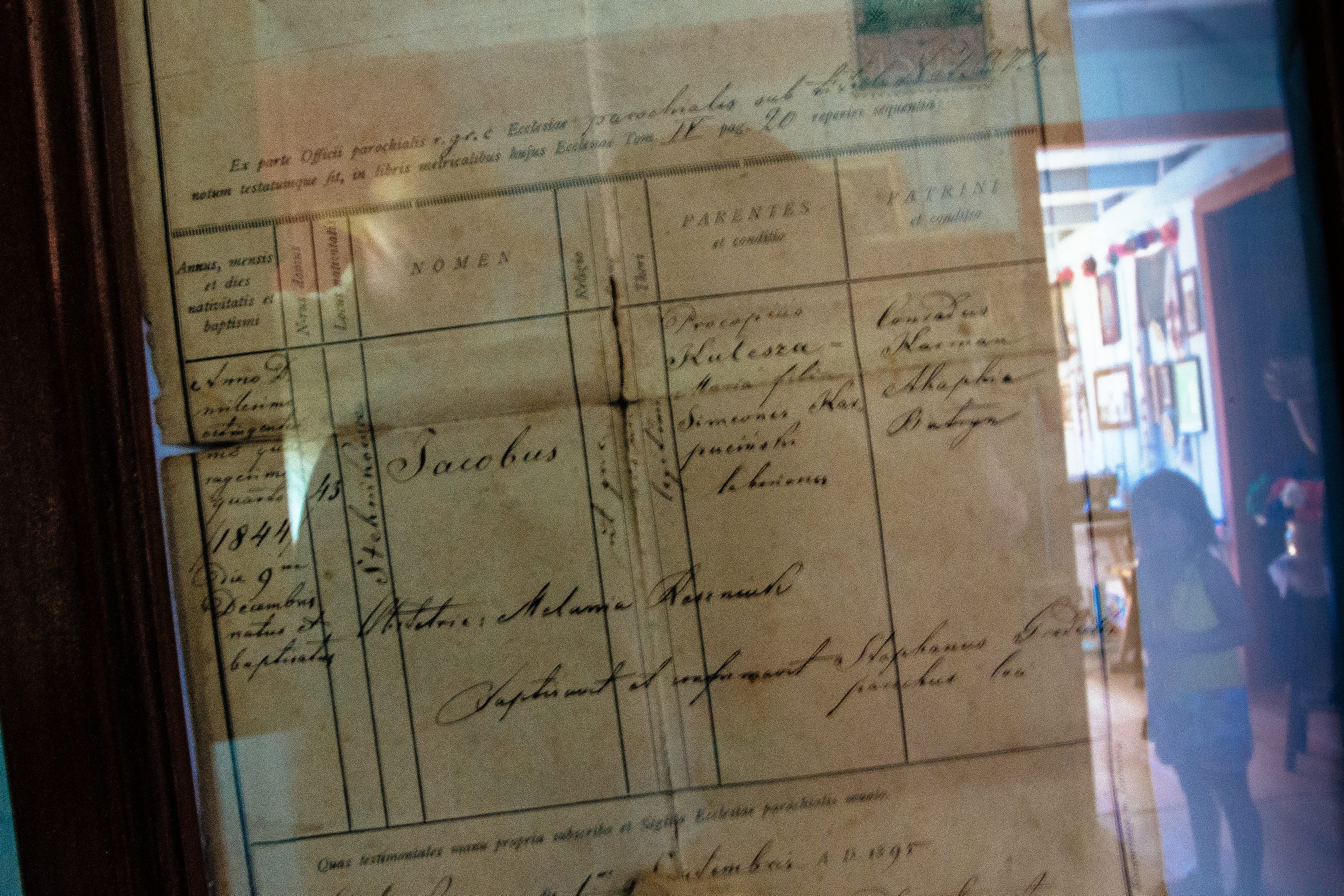

The struggle today is different: how to keep the culture alive and distinct after a century in Brazil. One front in this battle is the futuristically-named Museu do Milênio, the Millennium Museum, which carefully tends a collection of artifacts and tools used by the colonists in their early years in Brazil. Signs leading to the museum appear in both Portuguese and Ukrainian, a detail that museum director Meroslawa Krevey says is quite important. “The Ukrainian who comes here feels at home, as we feel when we [go to Ukraine].” It’s not an idle thought: one local travel agency specializes in bringing Brazilians to Ukraine, and Ukrainians to Prudentópolis.

There is, likewise, Ukrainian instruction in the public schools—when I visit one school, I see students talking to teachers in Portuguese and each other in Ukrainian. But it was not always so easy. At the end of the 30s, with the start of the “New State” and the outbreak of World War II, the government of Getúlio Vargas used national security as an excuse to ban the use of foreign languages in public, even in religious activities. The Pratsia, Ukrainian language newspaper, was closed. “We sat in class with the Brazilian students. [But] afterwards the catechist led us into the woods and there we climbed the trees while she dictated Ukrainian lessons from behind a pine tree, so as not to attract the attention of the authorities,” recalls Madeleine Zakaluguem Kolecha, 82. She now maintains a private museum with objects and photographs inherited from her parents and grandparents. Now she herself teaches her granddaughter Livia to speak Ukrainian. The Pratsia is back in circulation as well, and Ukrainian mass is broadcast on local radio.

This pride is on full display at the fifth annual Varéneke festival, which is timed to coincide with National Flag Day back in Ukraine. Ukrainian pop singer Tarás Kurchyk takes the stage singing a Ukrainian cover of “What A Wonderful World”. There is plenty more singing, Ukrainian flags draped around shoulders, and lighters in the air, and, of course, varéneke, stuffed Ukrainian dumplings. Cousins Alessandro and Stucki Juliano Gaiocha are in attendance as well. They tell me they have spent the last five years studying electromechanical engineering in Lviv, with support from Ukrainian government scholarships. They first learned Ukrainian in Brazil, though, at the farm where they lived with their families. As they found out, the language they learned was an archaic version of the language that had not evolved since their great-grandparents’ day. But they had little trouble fitting in, thanks in part to a traditional Brazilian export: football. The cousins made friends with the Brazilian players on FC Karpaty Lviv. There they met with players like William Batista, Eric de Oliveira Pereira and Danilo Avelar on weekends for barbecues and even feijoada with black beans harvested from seedlings that had been brought from Prudentópolis to Lviv. But the homesickness and the growing conflict forced them to come back home, where they are finishing their studies and living on the family farm once again.

The farmlands of Paraná are the center and lifeblood of the community. Bruno Pielak (who has Polish surname, but Ukrainian roots, a mixture from the time of immigration) is 19. He had moved away from the family, to try life in the big city, but returned after just four months and took over his grandparent’s farm. The adjustment has not been easy. He studied business administration and has encountered difficulties with the Paraná system of faxinal farming, wherein part of the land belongs to the community, and is used to pasture animals owned that are privately owned by individual families. It’s an admirable mix of communal and private property, but not above a certain level of cheating: Pielak says some producers who have little land but lots of animals are using an incommensurate amount of community land for their own benefit.

This might seem like a tangential concern, but to be Ukrainian in Prudentópolis means more than just wearing the flag at festivals. It also means continuing their unique form of social and agricultural organization. Thankfully, no blood will be spilled in the fight for the identity and unity of Brazil’s little Ukraine, but it’s still an essential struggle for Prudentópolis.