Barbara Wanjala writes about her short, ill-fated attempt to research democracy in a not-so-democratic country. On behalf of the Americans, of course.

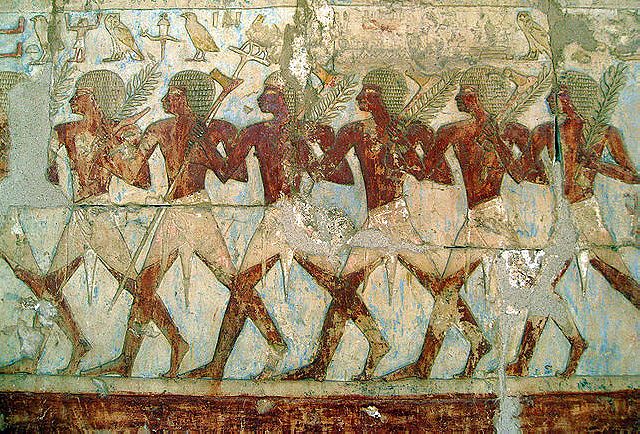

Land of Gods is a catchphrase used often in promoting Djibouti as a tourist destination. The Land of Gods referred to is the Land of Punt, a mysterious kingdom of untold wealth located to the south of ancient Egypt. Queen Hatshepsut referred to it as her “place of delight”. The exact location of Punt is disputed but historians have offered the possibilities of Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Yemen. Djibouti seems convinced it was their land. Wherever it lay, it was tremendously important. Queen Hatshepsut undertook an expedition to Punt, known as Ta netjeru in the ancient Egyptian tongue. Punt was a sacred place to the ancient Egyptians; they believed it to be the birthplace of both gods and men. It had commercial value as well: Egyptian fleets regularly crossed the Red Sea to trade in incense, ebony, gold, wild animals and more.

Djibouti’s crossroads location brings a different sort of visitor these days. “We are the gateway to the Middle East. That is why the Americans are here,” said Zaki as he sat with me in Djibouti Ville back in 2010.

We were in Sept Frères, a restaurant in the African Quarter famed for its moukbassa, a whole fish fresh from the Red Sea grilled in the Yemeni style and served with the Djiboutian flatbread lahoh and a sweet viscous purée of bananas and honey called houlba. Zaki was a tall, gaunt and solemn man in his early thirties. We had exchanged emails while I was still in my hometown of Nairobi in which I told him of my impending trip. I was coming to conduct a research project in Djibouti, on democracy. Funded, naturally, by the Americans.

My superiors at work had chosen me for this project because I spoke French. The client was an American NGO whose mission, we were told, was to educate the citizens of “undemocratic” lands about the virtues of democracy. They had written to my boss enquiring whether he had a field team in Djibouti and he had fired back a quick reply saying, rather disingenuously, that he had experienced men on the ground all over the country. Those men were imaginary; perhaps he believed that a man’s reach ought to exceed his grasp. Encouraged by his responsiveness and resourcefulness, the Americans wrote back saying they wanted to carry out a survey of Djiboutian citizenry’s attitudes towards democracy. The boss, seeing the possibility of a long and lucrative relationship with the Americans, agreed to take on the project. He drew up a timeline and a budget and emailed them to the Americans. Then he summoned me to his office and presented me with the job.

The American clients were scheduled to land in Djibouti on Sunday afternoon and wanted to meet the (still imaginary) field team for a briefing session upon arrival. The boss instructed me to depart immediately in order to set everything up before the American landing. This seemed impossible. It was Wednesday. It would take three working days to obtain a visa. He advised me not to bother going to the embassy. Instead, he said, I should travel on Thursday night to Addis Ababa in neighboring Ethiopia and then onward to Djibouti where I would arrive on Friday morning. He assured me that Friday was a slow and sleepy weekend day in the predominantly Muslim country and therefore immigration officials would be forgiving, allowing me to slip easily into the country sans visa. This clandestine suggestion gave me pause. Even if I managed to enter the country without a visa, where would I begin? I did not know anybody over there. Could he not stall the clients for a few more days while I tested the waters? He alternated between threatening and cajoling, saying time was a luxury that I did not have. I accepted the job.

Whatever you do, do not mention politics

The next morning I went to the embassy and waited nervously for my visa to be expedited. I had chosen to err on the side of caution and to enter the country legally. An older colleague at the office—a seasoned veteran of travel to “undemocratic” lands—had given me some welcome advice: “Whatever you do, do not mention politics. Say you are doing a comparative study on the eating habits of the wider Eastern African region instead.” It worked brilliantly. The bored embassy official was unprepared for my charm offensive. In my finest French and flashing my most dazzling smile, I expressed my deep and sincere interest in the food of Djibouti—its flatbread lahoh, its sweet halwo desserts, its baasto pasta. I even said I wanted to try camel meat. I left the embassy not only with a visa stamped in my passport but with a long and varied list of culinary delights that he insisted I try upon arrival in Djibouti. This seemed to augur well for the project.

At 2 am on Thursday morning, I presented myself at the Ethiopian Airlines check-in desk at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi. The two-hour flight to Addis Ababa was uneventful. I spent it familiarizing myself with the client’s very particular areas of inquiry.

I continued with these preparations during the four-hour layover at Bole Airport in Addis, pausing only for people-watching breaks. I was particularly fascinated by a large group of young women in loose floor-length dresses and shawls draped around their heads. A middle-aged Ethiopian seated beside me whispered to me that the contingent was Riyadh-bound, possibly victims of human traffickers masquerading as “foreign employment agencies” which lure unsuspecting young Ethiopian women with the promise of domestic work in the Middle East, where many fall into the hands of cruel employers and lead lives of servitude and suffering. Upon closer inspection, I noticed that many of the dresses were indeed new, and that many of the shawls were adjusted with a frequency that indicated either unfamiliarity or discomfort, and I wondered what lay in store for this seemingly upbeat and optimistic group.

Djibouti has the only American military base on the African continent

On the forty-minute flight from Addis to Ambouli, my eyes met those of an American soldier in seat 23C. He winked; I looked away. Djibouti is home to the only American military base on the African continent. Camp Lemonnier in the Djibouti Ville suburb of Ambouli is the American hub for the war on terror in the Horn of Africa, and no doubt at least a contributor to my clients’ interest in this tiny country. The soldier helped me with my luggage when we landed—muscular arms, many tattoos. He stood next to me on the bus ride to the terminal but we did not exchange a word. I bent into my purse to rummage for a pen with which to fill in the immigration form. When I raised my eyes to look for him, he was gone. I sighed, and moved along with the rest of the queue.

Surely the red-light district could not be in the center of the city?

Upon stepping outside into the sweltering heat I was promptly accosted by a sprightly old porter who forcibly steered me towards a taxi while carrying my luggage with surprising ease. He stuck out his palm and barked, “Trois dollars.” Three dollars. I obliged and entered the ramshackle vehicle. The elderly taxi driver greeted me cheerfully and introduced himself as Issa. He stroked his orange beard somewhat nefariously and asked where I would be staying. Tufts of matching curly orange hair peeked out of his white skullcap. I wanted to interrogate him on his henna dye job but felt it would be inappropriate.

“Hotel Ali Sabieh,” I replied.

He eyed me suspiciously. “Don’t you have any family?”

“None here,” I replied. I had obtained the hotel name from a hasty Google search for cheap hotels in close proximity to the university where I was planning to recruit my field team of bright, eager, cash-strapped students. Had I accidentally picked a seedy ‘love hotel’ in a disreputable part of town? Surely the red-light district could not be smack in the center of the city?

“Husband?”

“No.”

“Children?”

“No.”

He frowned disapprovingly. “That is not good. Once a woman stops having her period, it is over for her. Women must get married and have children quickly, when they are young.” He looked at me closely in the rear view mirror, no doubt trying to establish why I had failed to ensnare a husband by my advanced age of 25. “It is not good for a woman to travel alone and stay in hotels. People will talk. Also, your hotel is too expensive. I will take you to another one.”

And so Issa commandeered me to Hotel Banadir. It was a clean and utilitarian place, and once I ensured that there was a fan in the room, I paid cash upfront for two nights. Djibouti is said to be the world’s hottest country and already I had been wilting in the 40°C heat. Kadra, the pleasant and rotund cleaning lady, plied me with sugary coffee, freshly squeezed orange juice and a warm crispy baguette. She quickly took to lamenting the lack of good men in Djibouti as she straightened out my room. “All they do is chew khat,” she says angrily slapping a pillow into shape. It turns out that she, like me, was also unmarried. This left her extremely bitter about having to eke an honest living when all her four older (and significantly less attractive, according to her) sisters were all happily married with children. I commiserated.

After a refreshing shower, I slipped into a loose flowing dress I had packed with foresight for the hot weather. I went to the reception to call Zaki, my sole contact in the country who had been recommended by the seasoned veteran in the office. He knew someone in Nairobi’s predominantly Somali suburb of Eastleigh who knew someone in Somalia’s capital Mogadishu who knew someone in Djibouti. To my delight, I discovered that the hotel manager was an Omani Arab who wanted to practise his Arabized Swahili with me. After a labored conversation and several cups of sugary coffee, I finally managed to extricate myself and ventured out into the streets of Djibouti Ville, deserted on this hot and humid Friday afternoon, to meet up with him.

“We are the smallest country in the region,” Zaki had said as he tore apart his fish with his hands. “We are a desert nation with few natural resources. Those who say we have sold ourselves to the Americans do not understand our situation.” America might indeed be a good friend to have when one is surrounded by volatile and belligerent neighbors such as Somalia and Eritrea. While Djibouti has been committed to the Somali peace process, American military presence in Djibouti is a thorn in the side of Somali terror group al-Shabaab. The group reminded Djibouti that Somalia had sacrificed people and resources to aid them in their struggle for independence from the French. Signing a deal with U.S. President Obama on May 5, 2014 to let the US keep a military base in Djibouti for 30 more years was not the way to return the favor. The presence of foreign soldiers, both American and French, has been blamed for the increase in “un-Islamic behavior” among local women. On May 24, 2014, al-Shabaab carried out first suicide bombing in Djibouti’s history at La Chaumière, a restaurant popular with Westerners in Djibouti Ville. In a statement claiming responsibility for attack, al-Shabaab said that Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh had signed a “deal with the devil” by allowing access of its land and facilities to the “Crusaders”. In June, both Britain and the US issued travel advisories against Djibouti, citing credible threats by al-Shabaab to Western interests there.

The Americans are not the only ones interested in Djibouti. Tarek bin Laden, brother to Osama bin Laden, wants build a gigantic suspension bridge across the Red Sea to connect Yemen to Djibouti through the Bab el-Mandeb, a strait approximately 30 km long connecting North Eastern Africa to the South Western tip of the Arabian Peninsula. Bab el Mandeb means Gate of Tears in Arabic, named for the tears shed by the many that drowned when an earthquake separated Asia and Africa according to an Arab legend. It is estimated that about 30% of the world’s oil shipment transits through Bab el-Mandeb on a daily basis. Over 3.3 million barrels of oil are shipped daily from the Gulf States through the Red Sea and onto Europe and America. All this oil is why the high seas of the Gulf of Aden are a hotspot for pirates.

Zaki pointed out an elderly Arab man eating alone at a nearby table. “Very powerful guy that one. Has a band of young thugs on high-powered motorboats. They steal petrol from the big ships. They give us a bad name. Now the whole world thinks we are pirates like the Somalis.” This animosity with Somalia seems odd, given that the majority of Djiboutians are Somalis themselves. The country used to be known as French Somaliland. When Somalia was about to get independence in 1960, there was a referendum here to vote on whether French Somaliland should unite with Somalia. The Afars, a minority group somewhat favored by the French, and the French themselves did not want that and so Djibouti remained colonized until 1977, making it the last French colony in Africa to obtain independence.

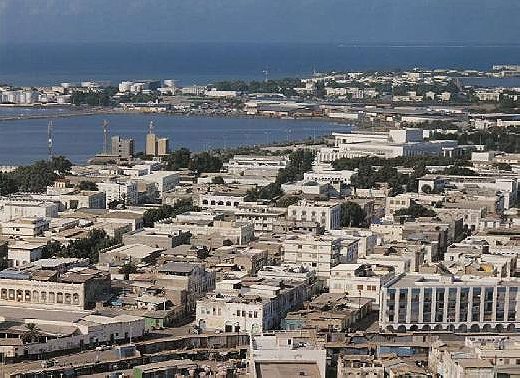

Djibouti Ville was once known as Little Paris and vestiges of French presence abound. There is a Boulevard du General de Gaulle and a cultural centre named after Arthur Rimbaud, the infamous French poet who abandoned Parisian bourgeois life to trade coffee and guns in the Horn of Africa. In the European Quarter’s Place Menelik cafés serve coffee and croissants while French legionnaires in uniform wander around. Like many of its African counterparts, the city is a study in contrasts. The African Quarter is a riotous mayhem of sights, sounds and smells. Aggressive vendors of clothes, food, spices, electronics and assorted counterfeit goods jostle with urchins, beggars, prostitutes, animals and loudly hooting minivan taxis. Picturesque Arab style arches can be seen in some of the older buildings, and the muezzin’s call to prayer from the city’s mosques wakes one in the early morning hours. This is Djibouti: a heady fusion of African, Arabic and European influences. As postprandial coffee was served in the Arab style, I outlined the project to Zaki.

I was here to test the political temperature of the country before the upcoming 2011 presidential elections on behalf of an American NGO client, and I needed Zaki to find willing focus group participants from all of the major towns of both genders and of varying ages, tribes, religions, political affiliations, levels of education, income and so on. As much diversity as possible was desirable. Could it be done?

“What kind of questions do you want to ask?” he asked suspiciously.

“What Djiboutians think of the government, whether you think the forthcoming elections will be free and fair, that sort of thing.”

“That is very dangerous. They will not allow you to ask these kinds of questions. You have to be very careful. You are risking imprisonment, not just for yourself but for me as well. If I decide to help you, that is.” He said there were severe restrictions on freedoms of speech, assembly and association. In addition, I was required by law to obtain a permit prior to conducting any research in the country. He said that the government would view this project as an American scheme to sow seeds of subversion among the Djiboutian people. This was worrisome news but he reassured me that we could get it done if we kept our wits about us and employed a bit of cunning.

The city is teeming with government spies and secret police

The first challenge was obtaining the research permit. The plan was to say that we wished to visit the country’s various regions in order to research the eating habits of the people. The second challenge was finding willing participants. Zaki told me that it would be difficult to find people who would voice their honest opinions about the country’s politics. However, he was sure that some financial incentive and the guarantee of anonymity would loosen a few tongues. He suggested hiring a bus to pick up the participants from the different towns to ferry them into the capital, holding the discussions at night then ferrying them back in the morning. He would also have to find a discreet location to hold the discussions in, a daunting task in a city teeming with government spies and secret police. We sketched out a plan of action and then he got on his phone to marshal his troops. I headed to an internet cafe to send a detailed update to the boss.

We met the American clients the next day. They looked perfectly at home in the luxurious opulence of the Kempinski, a hotel catering to those in search of international five-star service in a third-world setting. The vast lobby was swarming with Western military types in uniform, Arab businessmen in spotless white dishdashas, portly African diplomats and sunburned Western tourists. I introduced Zaki as the local field manager and they were suitably impressed by his knowledge of the country’s political situation. We informed them that a trial run of the discussions was scheduled for the next day.

Zaki did not think it is a good idea for the Americans to attend the discussions. The participants would not want to talk in the presence of foreigners. I told him not to worry; we would put them in an adjacent room with a Somali-English translator.

“The client is king,” I said, quoting one of the boss’ favorite mantras. “And they are only here for two days.”

Zaki nodded grudgingly. “You are right. We should keep them happy. I don’t think they want to leave their hotel in the first place.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Do you think foreigners come here to see the real Djibouti? No. They come here and ask for air-conditioning and high-speed internet. These are basic necessities to them. Most Djiboutians are struggling just to put food on the table.” He was working up an impressive lather of indignation, and I seized the opportunity.

“Isn’t the government to blame for that?”

Zaki unburdened. “The president is a dictator,” he said, referring to President Guelleh, one of just two presidents free Djibouti has ever had, who has been in power since 1999. “He pays lip service to progressive politics but runs the country on his own terms, which is to say repression and intimidation. He promises free and fair elections but reneges each time. Talk of increased democratic space is simply just that: talk. Instead of pursuing the goal of national development he is selling the country to foreigners. The chasm between the rich and the poor is expanding rapidly. This is the country we live in.”

After all that outrage, Zaki apparently needed a fix of khat—like his president, he is a devoted masticator of the narcotic stimulant that is flown in fresh daily from Ethiopia. I went with him to a street vendor where he bought a huge bag of the green leaves, and we then headed to his brother-in-law Abdkader, who lived a short ride away, past herds of languid camels, in the southern suburb of Balbala.

To my great delight, Zaki’s brother-in-law Abdkader had assembled members of his vast extended family to take part in the focus group. Zaki was from the majority Issa tribe whereas Abdkader was from the smaller Afar tribe. “They are more Somali and we are more Ethiopian,” Abdkader explained. In a country with a history of tribal animosities, he was understandably proud of his marriage to someone from a different tribe. He was a small and furtive man, a great contrast to his wife Fatiah who was tall with ample curves. The men had changed from their Western-style trousers into macawii, a length of colorfully printed cotton fastened securely at the waist and draped loosely down to the knees or the ankles like a skirt. After they had said their prayers, they sat down on the carpeted living floor chewing khat and conversing in rapid Somali. Fatiah brought bottles of cold Coca Cola to them. Apart from Fatiah, Abdkader’s elderly mother and myself, the rest of the women are nowhere in sight.

Zaki introduced me to the group, most of whose cheeks are bulging with wads of khat. I thanked them for their interest in the project. I stressed that the aim of the discussions was simply to find out what life was like for the average citizen of this country, and that I wanted to collect as many views as possible. They conferred among themselves in hushed tones, their jaws working furiously on the khat leaves. Zaki translated. They wanted a guarantee that their identities would not be revealed, and they would require a small financial token of appreciation. We agreed, and Fatiah and I went to the kitchen where the women were preparing the evening meal of rice and a spicy beef soup known as fahfahk. Afterwards as the evening got cooler, mattresses and bedding were spread out on the roof for the extended family guests. I headed back into town.

The trial run was a success. Several of the men and women from the night before took part in the discussion. Abdkader led while Zaki sat in the room next door with the Americans and me, translating from Somali into English. The group was timid at first, but gradually warmed up. Several of the men vehemently expressed their displeasure with the government, echoing Zaki’s sentiments from the previous day. The Americans nodded enthusiastically and scribbled the revelations in their notebooks. Once the group had left, they congratulated me on a job well done. They would be leaving for the U.S. tomorrow but expected me to send daily updates with the findings from the other towns. While Zaki was excited at the prospect of fanning embers of revolt nationwide, I only wanted to go back to my hotel room and sleep.

I was jolted awake by loud pounding on the door

No sooner had I fallen asleep than I was jolted awake by loud pounding on the door. I ignored it, hoping the unwanted visitor would tire and leave but the pounding did not stop. Suddenly I was afraid. While at Abdkader’s place, Zaki had recounted a cautionary tale about two Kenyans who were arrested and summarily deported for conducting research in the country illegally. Their photos were splashed in the local newspapers accompanied by severely excoriating articles. Overtaken by paranoia, I took my mobile phone and tiptoed to the bathroom where I quietly locked the door and dialed Zaki’s number. “They have come for me,” I whispered. He told me not to open the door, to pack my things and be ready to go when he arrived.

The pounding stopped after a while. I did as ordered and then sat down to torment myself by imagining the worst. My imaginings of Djiboutian prison conditions were interrupted by quiet tapping on the door, followed by Zaki’s voice. I let him in and apprised him of the past hour’s events. He feared the worst and told me that I was decamping to Abdkader’s. He was distrustful of the overly inquisitive Omani proprietor he had encountered downstairs. He said the man was probably calling the police as we spoke. I arrived at Abdkader’s to find that the news of my alleged imminent arrest has preceded me and created no small anxiety in my project participants. They no longer wished to take part in the research. I struggled desperately to salvage the situation, saying that it might not have been the police at my door. But the story has opened old wounds from the civil war twenty years ago: summary executions, imprisonment without trial, mysterious disappearances—fates that had befallen people they knew.

Feeling overwhelmed, I called my boss and asked him how to proceed. He said a more competent replacement would come to take over. When the replacement arrived, his first move was to offer more money to the participants. It was a very Kenyan response. The Djiboutians refused, their dignity slighted. “It is not worth the risk,” said an insulted Abdkader. The replacement then asked where we could find a new group of people, but Zaki said that nobody would agree to cooperate with him. Unwilling to accept defeat, the replacement set out to do the recruitment himself. Instead of going about it tactfully as per Zaki’s advice, he went to public spaces where being conspicuously foreign, he attracted the attention of the police. He was asked to produce his permit and failed to do so. The police advised to leave the country as soon as possible and not to trouble himself with returning. And thus the democracy project came to an unceremonious end.

On the return flight I was seated next to an elegant Djiboutian woman in her late 40s by the name of Amina. She was heading to Paris to visit relatives. She asked me whether I had enjoyed my stay in her country. I told that unfortunately I had not been able to see much of the country. “Did you not go clubbing? A young girl like you? How about deep-sea diving? Lac Assal?” Nothing, I replied. She appeared more disappointed than I was. “You will go back home and tell people that there is nothing to see in Djibouti which is not true.” It’s true that Djibouti is not a place people fall in love with—for many it is too hot, too poor, too dangerous, too bewildering. But I disagreed with Amina: I would have no bad report to make of the country. And for all the fiasco that was my American research project, at least as of this writing, I am still allowed to return.

“Will you be back?” asked Amina. “Yes,” I said, “I will be back.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities.