In Nigeria, a battle looms over how best to treat mental illness: modern psychiatry or faith healing?

IBADAN, Nigeria—

Al-Hajji Mojeed thinks of himself as a reformer. After he welcomed me to the offices of his Olaiya Naturalist Hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria, he lead me to a small, windowless room where a patient was shackled to a rusty engine block, recovering, as Mojeed put it, from “head surgery.” Three days earlier, Mojeed had used a razor blade to make a long incision in the patient’s scalp, then filled the gash with herbs in order to allow malevolent spirits to escape through the wound.

The room was the last in a row of cubbyhole-like shops that sit in front of Mojeed’s house, concrete painted sea-green, with double doors cut from the walls of shipping containers. Mojeed’s wife operates a hair salon in one of the rooms, small general stores rent two rooms in the middle, and at the other end of the row, Mojeed keeps a small office lined with shelves of herbal concoctions in recycled plastic water bottles.

Back in his room, Mojeed’s patient was sprawled out on a mat across the entrance, using his arms to shield his head as he slept. A chain around both ankles left him enough slack to sit up and face the street or to turn and lean against the wall. Beside him, his mother sat silently, smiling. She planned to stay with her son at Mojeed’s hospital for the next two months.

According to Mojeed, spirits had haunted the man periodically for 12 years. Before the surgery, he was hostile and violent. When his family delivered him into Mojeed’s care, they brought him with his hands and feet bound with rope. The patient had been cursed by debtors in a business deal gone bad, Mojeed said, and his family had taken him to a series of spiritual healers with no change for the better. Standing in the doorway, Mojeed was ready to declare the surgery a success. “That is why he is sleeping,” Mojeed said. “The medicine is taking effect.”

Professional psychiatric care is basically inaccessible for most Nigerians with psychosis, a term used to describe a broad range of conditions that involve some disconnect from reality, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Fewer than 200 psychiatrists work in a country of 168 million, and since Nigerians usually consider psychosis a supernatural affliction, psychiatrists are rarely seen first, if at all.

Fewer than 200 psychiatrists work in a country of 168 million.

Increase Adeosun, a psychiatrist who manages intake at Nigeria’s largest psychiatric hospital, says patients usually only turn up there when the symptoms have reached a “melting point, when every other [option] has failed.” Most have already put in long stints at churches and mosques—where they are often subjected to fasting and periods of isolation—or in centers run by traditional healers. Flogging and shackling patients is sometimes practiced at all three. The clinical rule of thumb for psychotic disorders, meanwhile, is “the shorter the onset, the better the prognosis,” Adeosun says. As a result, psychiatrists typically find themselves treating the “treatment” as well as the illness, with many patients suffering from symptoms that have been exacerbated by the work of other healers.

But spiritualists like Mojeed represent the only consistent frontline psychiatric care in Nigeria. Whether they’re Christians, Muslims, or animist complementary providers (medical jargon for traditional and faith healers), they are present in nearly every community in the country. In Ibadan, Nigeria’s second largest city, a single Muslim healer operates a facility that houses twice as many patients as the only psychiatric ward in town. For Nigeria’s medical professionals, the trick is to convince spiritual healers to modify their treatments and even refer some cases to clinical doctors. If that type of collaboration happened on a large-scale, it could transform the prognosis for thousands of people suffering from acute mental illnesses.

That’s exactly the cooperation that Ibadan psychiatrist Oye Gureje is hoping to encourage. He’s the principal investigator of a six-country research project called the Partnership for Mental Health Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Gureje says that the goal of the program, which is funded by the U.S.-based National Institutes of Health, is to design a collaborative “shared care” program between professional psychiatrists and traditional healers. The hope is to spare patients from the most harmful practices, and ideally, have some referred to specialists for treatment sooner rather than later. African medical literature is rich with studies on how both patients and practitioners view mental illness and its causes, but this is the first research project devoted to evaluating the feasibility and benefits of psychiatrists and traditional healers practicing in tandem. “We don’t really know how it will work,” says Gureje. “We just have to wait and see.”

It’s clear that Gureje would like to see the traditional healers phased out immediately. But he has to be more pragmatic. “It will be decades before we have enough psychiatrists in Nigeria to meet the need. Until we’re able to convince people that their worldview is wrong, that there is no supernatural causation of mental illness, these people are going to be patronized,” says Gureje. “If that is the case, what can we do to make their practice less harmful, to make it beneficial to patients?”

For his part, Mojeed seems like an unlikely candidate for compromise. Although the head surgeries he performs are technically illegal, he believes in the procedure and views Western medicine as ineffective against psychosis. There may be physical causes for anxiety and depression, but psychosis, Mojeed explained using a Quranic term for spirits, is caused by “djinns taking over a person’s mind.”

Where psychiatrists see cycles of remission and relapse, traditional healers see the failure of Western medicine. “The treatment at UCH doesn’t reach the brain,” Mojeed said, referring to the University College Hospital of Ibadan. “It only manages, never heals.” His consultation room is decorated with local news clippings heralding outright cures against the odds: “Madwoman completely healed after 21 years,” one reads. Since 1997, Mojeed has run an association called Atorise—in Yoruba, the name means “repairer of heads”—organizing the ranks of Ibadan’s traditional mental health practitioners with an eye towards proving their legitimacy to the Nigerian medical establishment. Last year, Mojeed suggested that the university hospital should refer patients to him they are unable to cure, a proposition he says they rejected out of hand.

As horrifying as Mojeed’s methods may sound, he is considered more progressive than most. Wole Adejayan, a researcher at UCH, says Mojeed stands out among dozens of traditional healers for his efforts to temper the methods used by his colleagues. Through Atorise, Adejayan says Mojeed has argued against beating or withholding food from patients. His facility is one of only a handful that requires the presence of a caretaker alongside the patient for the duration of the treatment.

Indeed, a few decades ago, techniques performed in U.S. asylums were every bit as cruel. A 1946 article in Life describes life-threatening beatings routinely visited on inmates of psychiatric hospitals by their attendants, as well as long periods of confinement in dank cells where patients slept on the ground and wore thick leather handcuffs. Three years later, in 1949, a Portuguese neurologist won the Nobel Prize for developing the lobotomy—a procedure no doctor today would recommend. Insulin shock therapy, designed to induce a coma-like state in schizophrenic patients, was common in the United States through the 1950s.

Mojeed remains leery of participating in collaborative treatment for psychosis. His concern is actually based on medicine; he’s worried about the possibility of negative interactions between pharmaceutical drugs and the sedative, plant-based concoctions he gives his patients. Unless, that is, it could be done sequentially by making referrals when one form of treatment proves ineffective. In that case, he said, “If the government will provide shelter and food for patients, members of Atorise will provide our services for free.”

Other faith healers are similarly open-minded. In Ibadan, I spoke to a pharmacist who says he periodically sells Largactil—the anti-psychotic chlorpromazine—to robe-wearing pastors who administer the drugs dissolved as a cocktail in a glass of holy water.

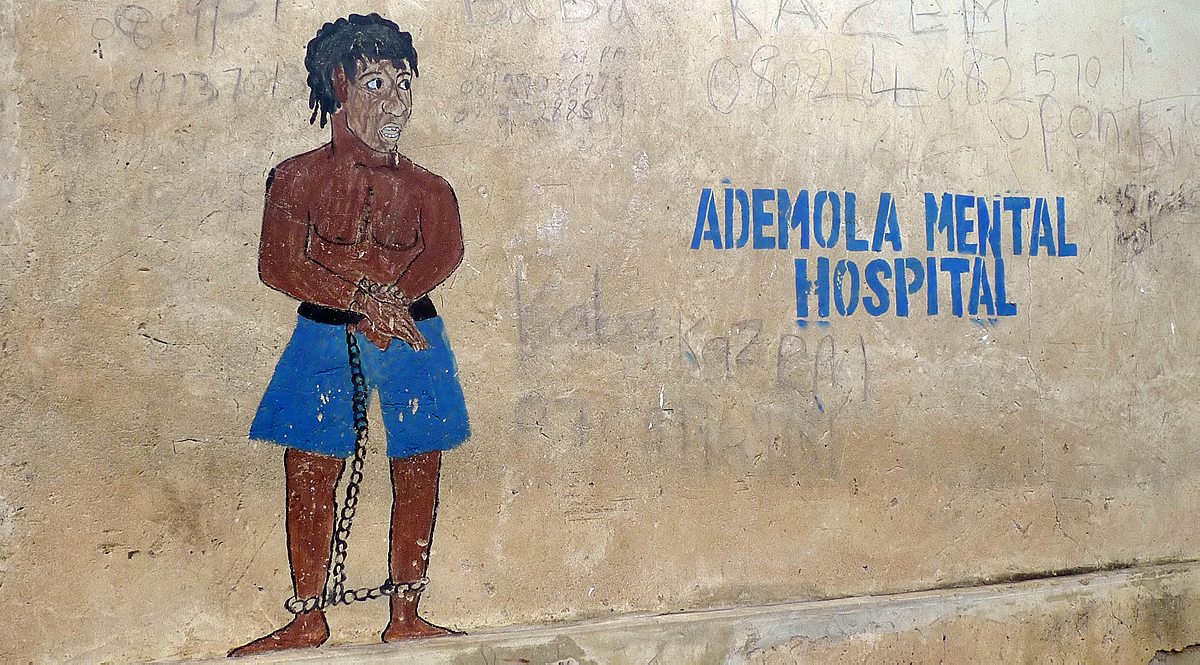

When I visited in the middle of October, two patients were chained to pillars on the front porch.

One problem, as with so much in Nigeria, is money. Psychiatric treatment is expensive, and even the government can’t always pay its hospital bills. In July, when Ogun State’s funds were tight, officials stopped sending homeless patients with severe mental illness to a more expensive government-run psychiatric hospital, instead opting for Ademola Mental Hospital. Ademola is a traditional healing center that practices diagnosis by incantation, reciting verses to invoke the presence of Gods responsible for mental illness. When I visited in the middle of October, two patients were chained to pillars on the front porch.

It’s hard not to see psychiatric hospitals and traditional healers remaining in direct competition. For now, though, it’s the psychiatrists whose livelihood seems most uncertain. Last month, residents in Nigeria’s public hospitals went on strike for more than three weeks; some doctors hadn’t been paid in more than four months. Most patients were left to look elsewhere for treatment.

This story was made possible by a grant from the International Reporting Project (IRP)