British-born photographer Nick Brandt has been documenting East Africa’s disappearing grandeur for more than a decade in his trilogy of books: “On This Earth, A Shadow Falls Across the Ravaged Land.”

On Thursday, November 14th, 2013, the United States crushed six tons of ivory in Denver. Now reduced to dust, the shattered pile of white gold represented well over a thousand slaughtered elephants. It was, in some ways, a historic moment and a clear step up in the country’s role to combat the illicit trade. But there’s much more work to do. Last year alone, experts say that more than 30,000 elephants were slaughtered for their tusks. British-born photographer Nick Brandt has been documenting East Africa’s disappearing grandeur for more than a decade. His trilogy of books – “On This Earth” (2005), “A Shadow Falls” (2009), “Across the Ravaged Land” (2013)—was just completed in September of this year, and the last installment is the grimmest one so far. He spoke to us the day after attending the ivory crush.

Roads & Kingdoms: What was the ivory crush like?

Nick Brandt: It was an important but sad moment, to see the tusks of so many hundreds and hundreds of elephants ground up into deliberately valueless dust, elephants whose lives were lost for naught, like all the millions of others whose lives over the decades have been brutally and needlessly extinguished for their ivory….

R&K: Is it something that happens often?

NB: It was the first ever in the US. I was invited by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who gives funds to my foundation in Africa, Big Life Foundation. It was the first step in what will hopefully lead to a more actively engaged United States entering the battle to stop the out-of-control slaughter of Africa’s last elephants. In and of itself, this ivory crush will make no difference to the ivory demand. But it is an important start. The U.S. now needs to more urgently try and engage all countries to more forcefully impose the ban on illegal ivory. But the U.S. needs to do something else to make a dent in the killing: what many of us don’t realize is that after China, the U.S. is actually the second largest importer of illegal wildlife parts. Not ivory specifically, but all illegal wildlife parts. The U.S. cannot hope to ask China to do the right thing and ban ivory whilst it allows the sale of ‘legal’ ivory to continue in this country.

R&K: What can the U.S. do to set a good example?

NB: The U.S. needs to impose a moratorium on the sale of all ivory products in the country. The vast majority of ivory is illegal, sourced from murdered elephants. But retailers of ivory products invariably claim that their ivory is legal, when in truth, it is anything but. The loophole is so large that you could drop an entire herd of elephants through it. This moratorium should be an easy sell, but as always, there is a strong faction in the form of the deceptively benignly-named Safari Club, who will fight this to the (species’) death.

R&K: I had no idea the U.S. was such a big importer.

NB: Nor did I to be honest.

R&K: Why do you think that is? And do they import the same things as the Chinese?

NB: Because of money. Tusks and rhino horn, less so—that is heavily to China and the Far East. But there are many, many other illegal animal parts from other parts of the world.

R&K: So to go back a little bit, you were a photographer before you became an activist..

NB: I am a photographer. Present tense. But yes, there was no choice. I couldn’t stand on the sidelines any longer and watch the destruction continue and do nothing. With the wealthy collectors of my photographs, I was very fortunate to be able to approach some for funding to start Big Life and start protecting the 2 million acre Amboseli ecosystem.

R&K: You had already published two books on the subject by that point. Why is this final one the darkest?

NB: The progression of tone in the books is very deliberate—from the natural world of Africa viewed as a kind of Eden, a paradise, in the first book; to the shadow of man’s destructive influence beginning to appear in the second book; and to the third… Sorry, I’m looking for the right word… In the third book, I could no longer ignore what was happening in Africa: the dramatic escalation of destruction of that world, due to a significant degree to the demand for animal parts from the Far East. I always knew that this amazing world was disappearing, but never expected it to escalate at this rate.

Working with the local communities is the only feasible chance we stand.

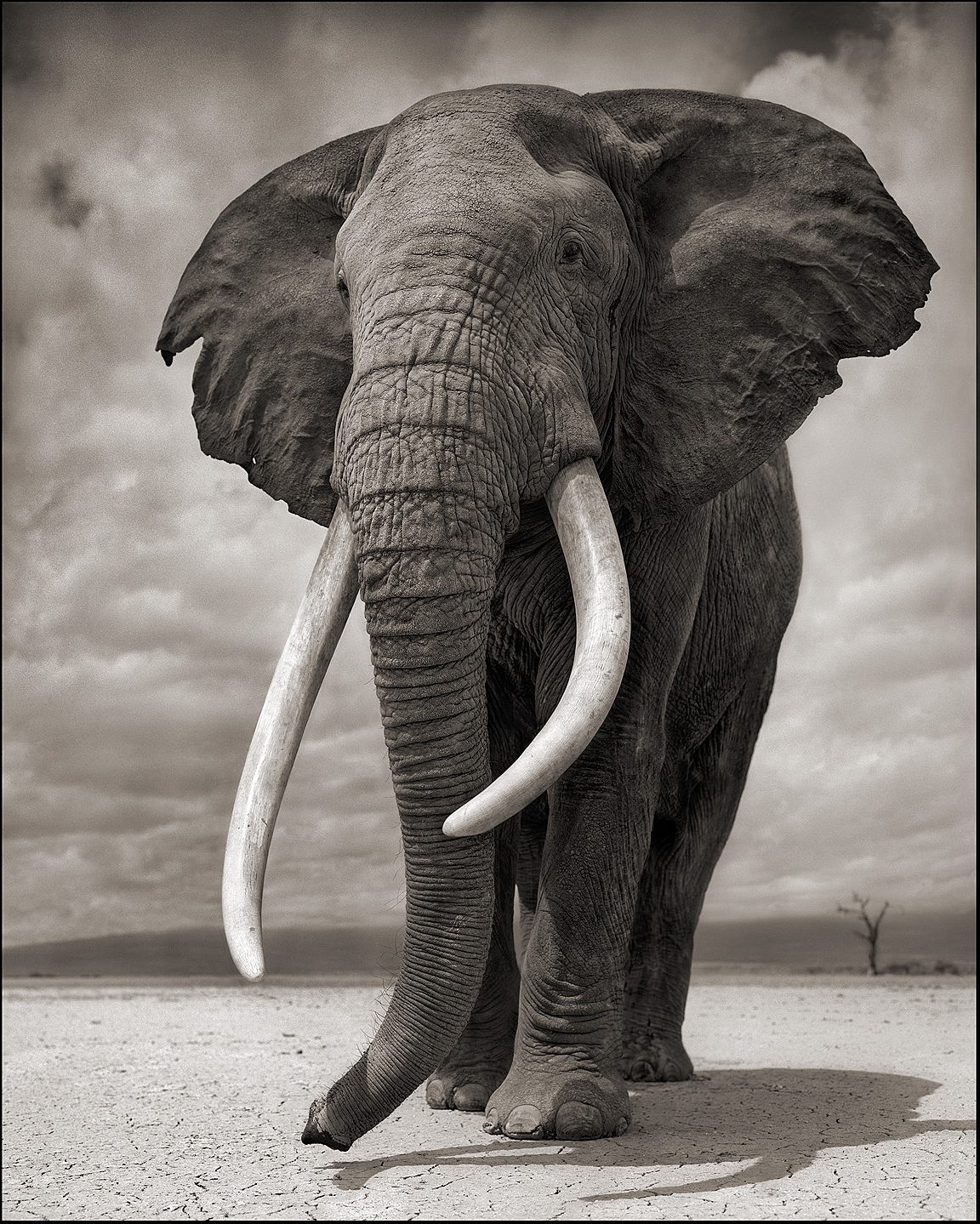

R&K: Throughout the books, however, you’ve always kept this very specific style of shooting, which makes the animals look like they come from a bygone era…

NB: It goes back to my feeling, from the outset, that I was photographing a world that was disappearing. The black and white film, the soft light, the medium format portraiture all lend themselves to the sensibility of the photos coming from an earlier era, as if these animals were already dead. Secondly, I have always viewed animals as sentient creatures not so different from us, and so photograph them in the same way I would human beings. I just have to be more patient when waiting for them to present themselves for their portraits.

R&K: Have you seen the animals’ behavior towards humans (and you) change over the years?

NB: In July 2010, I returned for the first time in two years to the Amboseli ecosystem. Day after day, we tried to approach what had once been some of the most relaxed of elephant herds, elephants that in the past had quietly made their daily journey to the swamps, moving past and around our vehicle without a care in the world. But this time, they would run in terrified panic. Gunshots were being reported from the direction that the elephants came, near the Tanzanian border. We tried reporting what we’d seen, but nothing was done. The Kenya Wildlife Service was (and still is) underfunded, and the few NGOs in the area had insufficient funds and infrastructure to make much of a difference. On the Tanzanian side, there was no one at all engaged in protection or conservation. Just six weeks after I took the photo below of Winston, a thirty-year-old elephant barely into his prime, he was shot by poachers over the border in Tanzania. Wounded, he made it back over to Kenya, where he died. He also had his tusks sown out of his face with a power saw by the poachers. Many of the elephants are still alive when the chainsaw, or ax starts hacking the ivory out of their faces.

R&K: I’m very interested in the few people you include. At first glance, I thought they were poachers. But it’s actually quite the opposite…

NB: Interesting. Yes, they are the protectors, not the destroyers. If animal populations and attendant ecosystems across Africa are to stand a chance of surviving into the future, working with the local communities is the only feasible chance we stand. This is Big Life’s ethos, the only way for the future: conservation supports the people, the people support the conservation. We have 310 rangers, all locally employed. But you cannot hope to protect 2 million acres with just them. The local community, seeing the economic benefit of conservation, acts as one vast network of information for when poachers come in, alerting the rangers to their presence.

R&K: Your foundation created the first trans-border anti-poaching operation in East Africa. Why was that so important?

NB: Before Big Life, poachers from Tanzania would cross the border into Kenya and kill the elephants there, escaping back over the border with impunity. Now, as the only organization in East Africa with co-ordinated cross border patrols, the rangers on the Kenyan side can call the Tanzanian side with co-ordinates to intercept the poachers. Except they don’t need to anymore as the poaching has been so reduced for now in the area the rangers patrol.

R&K: The book as a whole is kind of a throwback—I mean, the way Africa is portrayed is far from the rapidly urbanizing continent we often see in the news now. This isn’t the Africa that most Africans experience…

NB: Correct. Most have never seen an elephant or lion in the flesh. And now most never will. It’s how I like to photograph. I’m not interested in color or digital. And modern, urban Africa is not relevant to what I am photographing. The poaching crimes are being committed to satisfy the demand abroad. But there is also an increasing human wildlife conflict that is hugely problematic. Human population is rapidly expanding into areas that until now were the sole domain of animals. As a result, there is increasing conflict between man and animal. Increasingly, with man encroaching into where the animals live, animals such as elephants now invade farmers’ crops, and animals such as lions kill their livestock. Attempts at retribution can be swift and common, with elephants speared and lions poisoned or speared. In the Amboseli ecosystem, due to our success in reducing poaching, more animals are currently lost in human-wildlife conflicts than to poaching. As a result, every night, three Big Life vehicles patrol the farms in the foothills of Kilimanjaro, ready to respond to reports of elephants trampling farmers’ crops. Thunderflashes, noisy harmless pyrotechnics, and chili “bombs” are used to scare off the elephants. Crop raiding is down in the region, but still present. Big Life also has a Predator Compensation Fund that compensates livestock owners for the loss of their animals to lions and other predators. It’s expensive, but it works, keeping the lion population of the ecosystem steady so far.

If you’re interested in getting involved, visit the Big Life Foundation. You can see more of Nick Brandt’s work on his website, or buy his latest book here.