A conversation with Xenia Nikolskaya on her portraits of Egypt’s decaying palaces

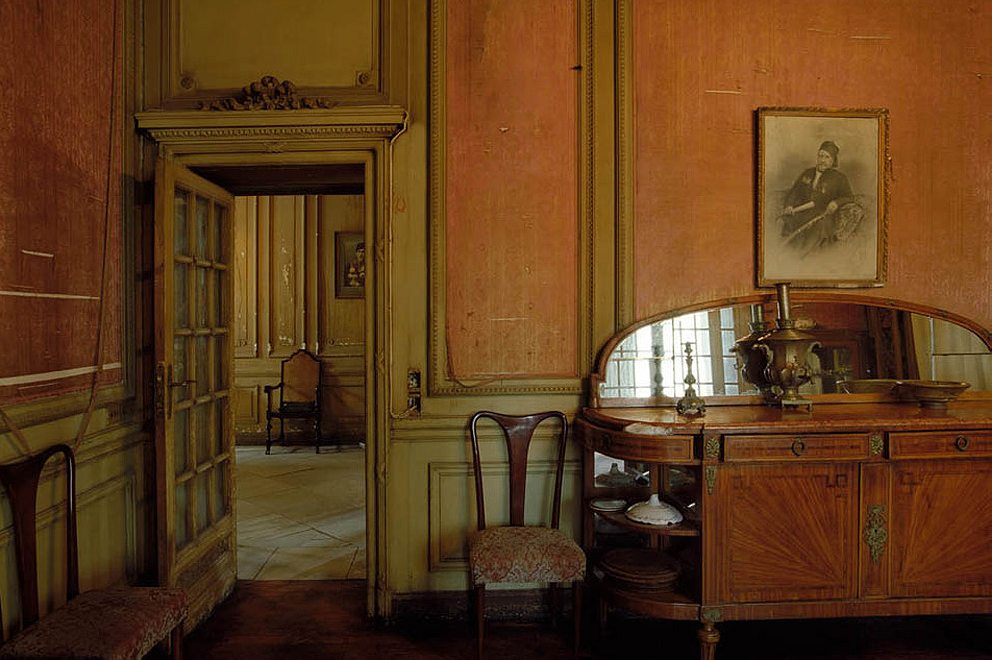

I reached photographer Xenia Nikolskaya in Moscow while she was on an assignment for her new job as director for education and exhibition projects at Russia’s RIA Novosti news agency. She gamely answered questions from her iPad while on a break, but the topic was far from mid-winter Moscow. It was, instead, about her extraordinary book DUST: Egypt’s Forgotten Architecture. The book documents the abandoned palaces and salons of an Egypt you don’t often see in the headlines: the golden age of Cairene opulence.

But Nikolskaya’s interiors, shot from Esna in the south to Port Said in the northeast, largely with an old Horseman 6×9 camera, say as much about the decay of modern Egypt as about the luster of the country’s early years. Nasser may have kicked the wealthy owners of these mansions out of Egypt, but it was Mubarak who oversaw the political and financial rot that allowed a country to let its own history fall into such disrepair. And Mohamed Morsi’s new government doesn’t seem to value its cultural patrimony any more than its predecessors.

An exhibition of Nikolskaya’s work opened this weekend at the Medelhavsmuseet in Stockholm. If you, like me, won’t be making it to Sweden in the next little while, you might instead enjoy this (slightly) edited version of our conversation.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did you originally find your way from Russia to Cairo? I thought most Russians in Egypt stay in Dahab or Sharm.

Xenia Nikolskaya:Well, I am not most Russians… My grandmother is Danish. And my husband is Swedish.

R&K: Such handsome men.

XN: Oh yes they are. And strong. Vikings!

R&K: Tell me about how your book Dust started out.

XN: The first time I got to Cairo was in 2003, but it wasn’t until 2006 that I discovered this unknown—for me at least—colonial architecture that looks like my home city St. Petersburg.

R&K: Throughout Cairo, or in one area in particular?

XN: It was one house I first saw and got inside. It is on the cover of the book: the Sarageldin Palace in Garden City, next to my apartment now. I got inside and got in touch with relatives of the original owners. I made a small story about it, [but] no one could believe it is Egypt… I was truly amazed that Egypt has 5000 years of history, but the urban environment is [no more than 140] years old, literally. So in the end of XIX century Egypt was an architectural playground for politicians, business people, Egyptians and foreigners. People with money.

R&K: Your interview with Polis goes into the history well. Why was that detailed history important to include? Why not just let the photos, the interiors, speak for themselves?

XN: [The abandoned buildings are] a portrait of the very important time, an Egypt that nobody knows about. So I worked with historians and architects. And it remind me home [St. Petersburg] in a way. But you can’t do it at home. It’s too personal. Back home if I saw something like this I would cry, but not take pictures.

R&K: The old buildings there are in much less danger than in Cairo, yes?

XN: Less so, but still in danger.

R&K: I am not sure I’ve seen a shot of Cairo with no people in it. And now you have a whole book of them.

XN: Absence in Cairo is a luxury you never face. I wanted to do something that looks totally not Egyptian. Something about absence like Vermeer paintings. I got this idea in New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 2009 when I saw Vermeer’s Milkmaid. In this case ‘dust’ is a metaphor of it. And of course on the other side it is a portrait of Mubarak’s Egypt and the stagnation.

Some got burned and looted, some destroyed.

R&K: The project finished at the end of 2011. What has changed with these buildings since then after the revolution?

XN: Some got burned and looted, some destroyed. I am trying to follow up and record video interviews about them.

R&K: How sad. Which ones?

XN: Casgaldy villa, the Geographical Society. Some got “renovated”.

R&K: What does that mean?

XN: It means stupidly cheap fast painting all over, or something else that destroys the atmosphere.

R&K: Are there forces or organizations trying to preserve them now?

XN: Well, my book got a lot of attention and it created discussions about heritage. There are some organizations, but Egyptians are too busy with other stuff. And architectural heritage is a luxury problem.

R&K: Why do you think it should be something that post-revolution Egyptians should care about? Why is it important?

XN: It is a history. They should learn by their own experience. History is a knowledge. Knowledge is a result of education. [But] in Egypt about 50% of population—57% of women, for example—can’t read or write. Education is a key for everything.

R&K: You said that your book started conversations about heritage. Where? On blogs? At universities?

XN: Blogs of course. There is a great blog, the Cairo Observer, written by my friend Mohamed Elshahed, [that talks about how] architecture reflects economical and political decisions.

R&K: Has the Morsi government made any move, positive or negative, on the topics of these old buildings?

XN: Morsi’s government did nothing about nothing. It is a joke. People from outside don’t really know he was elected. By 10% of Egyptians. The rest did not vote at all.

R&K: Not that the situations are the same, but the Islamists from Timbuktu to Bamayan are very concerned with erasing history. Does the Muslim brotherhood, in your mind, have the same goals?

XN: Of course religious fanatics are not interested in educated, smart people. How can they manipulate them?

—

For more from Xenia Nikolskaya, visit her website or follow her on Twitter at @XNikolskaya