How the ghost of socialist President Salvador Allende is changing Chile.

SANTIAGO, Chile

“We’re going to make history today!” says the MC, a heavyset hype-man in an orange hoodie, as Latin rock pumps through the northeast corner of the Plaza de Armas. “A thousand people in Allende’s glasses! Yeah!” Campaign workers leave the stage with cardboard boxes full of imitation glasses—plastic lenses in the same kind of chunky black frames that the Chilean president wore up until the day he killed himself in the presidential palace as Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s forces bombed the building. The crowd, several thousands strong, surges against the barricades to grab the glasses.

Amid a spike in Salvador Allende’s popularity, particularly among younger Chileans, those glasses are icons—stenciled on sidewalks, printed on t-shirts, the inspiration for songs like “Allende’s Glasses” by Manuel García. And in the midst of a heated presidential campaign that just happens to fall on the 40th anniversary of Allende’s death, one could be mistaken for thinking that Allende himself was on the ballot.

The question of Allende v. Pinochet is not a trivial one in Chilean society. The 17-year dictatorship that followed the 1973 coup left 3,200 dead, nearly 30,000 victims of torture, and a seemingly permanent rift in society. In the 1988 vote that ended Pinochet’s reign, the general still won the support of more than 43 percent of voters. This anniversary has featured a wave of new revelations, however, including the hit documentary series Imagenes Prohibidas, which transfixed the country with never-before-aired footage of the coup and its aftermath. More institutions like Santiago’s Museum of Memory are doing the hard work of cataloging the facts of military rule. But Chile has been torn by a more elemental question for four decades: Was Allende a martyr for his country or a Marxist leading the country to ruin? People’s answers to some of the big challenges facing the country today—education, health care, inequality—often depends on how they feel about the past.

And so Allende’s legacy is debated among the two leading candidates in the race, center-left former president Michelle Bachelet and her conservative opponent Sen. Evelyn Matthei, whose connections to the 1973 coup—and to each other—have been well-documented. (Short version: their fathers were both Air Force generals and friends before the coup; Bachelet’s father sided with Allende and died for it, Matthei’s father ended up joining the junta, and she voted in favor of Pinochet in the 1988 plebiscite).

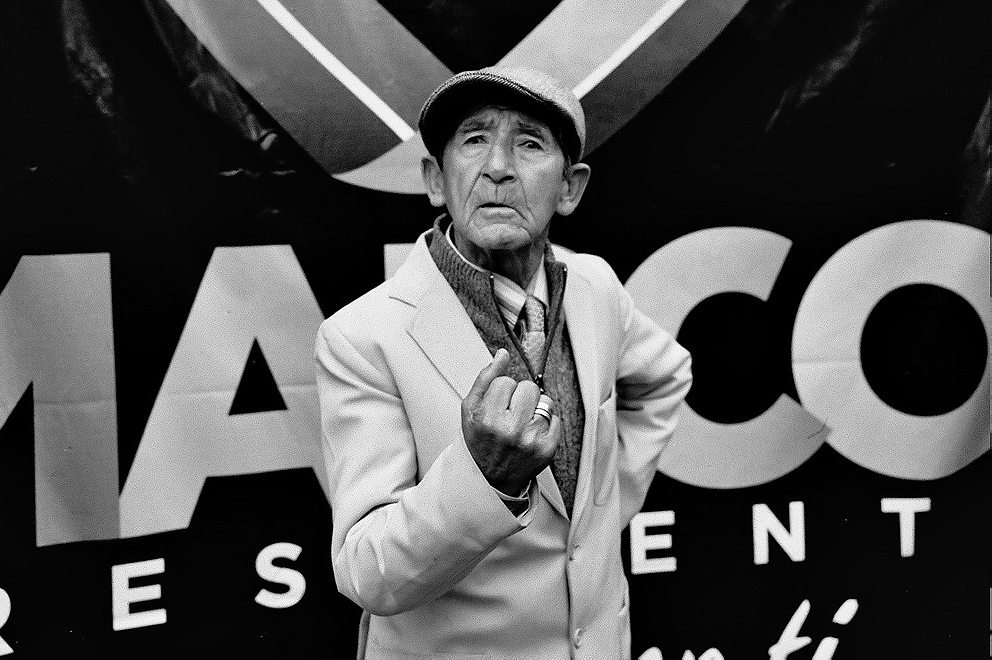

But the rally with the fake glasses is a campaign event for the candidate who is the most direct ideological heir of Allende—a robust socialist named Marco Enriquez-Ominami, who believes in a social safety net, strong public schools, and public health care. Of his core supporters in the VIP section in front of the stage, only half are waving his Marco: Always for You flags. The other half are waving flags with Allende’s face, or ones that say Socialista Allendista on it. His political party, the PRO, has a host of local and regional candidates at the event, and they’re all wearing Allende t-shirts.

Enriquez-Ominami, who often goes by his initials MEO, appears to be running on a sort of double-ticket with the martyred president. The former documentary filmmaker has a puckish charm to him, more than a little Gallic—he was raised in Paris—with half-long hair and a wry sense of humor. He ran an insurgent presidential campaign four years ago that almost overturned Chilean politics—his 20 percent was nearly enough to force his way into the presidential run-off. This time around he has gone more conventional, trying to organize a political party that might challenge Bachelet from the left. If Bachelet is the mild voice of reconciliation—“When I came into [the presidency] I never asked anyone, ‘Did you work for the dictatorship?’” she told me. “I am not the kind of person who says winner take all”—MEO is the guy shouting for remembrance and redress.

He says this isn’t so, and the 40-year-old candidate uses his youth to say he’s unburdened by the past. “I’m a son of the coup,” he likes to say, “not a slave of it.” But his history is every bit as tied to the bitter memories of the past as his opponents’. His biological father Miguel Enriquez was something akin to the Che Guevara of Chile, a medical doctor from an elite family who decided to take up arms in the 1960s in support of a Marxist insurgency. “My father robbed banks to finance the armed revolution and help the poorest of the poor,” says MEO. “He robbed many banks.” When the coup happened, the father sent MEO, then just months old, into hiding. The family changed the infant’s name and smuggled him out of the country, where he grew up in exile in Paris, eventually adding the name of his adopted father. Miguel Enriquez stayed behind, and died in 1975 after Pinochet’s forces found his safehouse in Santiago. Unlike other leftist leaders who had access to money, he did not flee the coup; he stayed to die. “I feel a great pride, a great respect for my father,” he says. “But he was a fighter; I’m a politician. These are different moments in our history.”

MEO says that his father stood out in Chilean history because, as a friend and advisor to Allende, he was one of the few who warned the president that the military planned to kill him. And, despite his protestations that his campaign is unconnected to the past, it is clear that MEO has scores to settle with the vestiges of the Chilean right. “Everyone knows Bachelet is going to win,” he says. “But if I come in second place in this race [ahead of Matthei], it will be the completion of the transition to democracy, the end of the old conservative movement.”

If anything, Chilean society is moving toward MEO’s view of history, absolving Allende and apportioning more blame to the right. A survey this summer showed that 41 percent of Chileans thought that Pinochet was responsible for the coup, up from 24 percent a decade ago. Those holding Allende responsible fell from 13 percent to 9 percent. In a perhaps less rigorous measure in 2008, the half-academic, half-plebiscite show Grandes Chilenos voted Allende the Greatest Chilean in History. When I interviewed Chilean President Sebastian Piñera for TIME, he began with a typical conservative disclaimer to the coup: though democratically elected, Allende had begun consorting with Fidel Castro and veering the country toward Marxism. That unilateral leftism was the “real picture” of the Allende government that the “international community and the press didn’t show.” But Piñera then talked about the “romantic” nature of Allende’s suicide. (He shot himself in a seldom-visited salon near the First Lady’s current offices.) “For young people,” he said, “Allende is like a legend.” His administration has not only maintained funding for the Museum of Memory that chronicled the victims of the violence, but it has given Allende’s statue outside La Moneda presidential palace a new coat of paint.

That legend is not likely enough to push MEO into another miracle finish. Bachelet’s candidacy remains strong, and some of the novelty of his reappearance—the son of Chile’s greatest armed Marxist—may have has worn off since four years ago. He is only polling at 9 percent (to Matthei’s 14 percent, with Bachelet far ahead of both) in a recent survey. But back in the Plaza de las Armas, MEO’s approval ratings seem beside the point. The crowd, Chileans from all walks now wearing their free black-rimmed glasses, cheers Allende’s last words as they play on a jumbotron above the stage. MEO doesn’t really have to win. Allende already has.

[Top image and slideshow by Michael Magers for Roads & Kingdoms]