One man is building an entire industry from the ground up in a remote region betting big on a new superfood. But is camel milk the next snake oil?

“Just drink one more shot and then I’ll give you the antidote,” Chen Gangliang, the founder of China’s only camel milk company, slurs at me. We are in the sandy desert of western China but in the middle of a fish banquet, harvested from the area’s two freshwater lakes, which were supposedly formed from the footprints of an ancient, celestial horse. The plates of freshwater pike, tiny fried silver fish, and dumplings whose wrapper is actually pounded fish have long since been cleared, and now we are deep into the baijiu, the Chinese firewater I once watched a mechanic use to clean the rust off of motorcycle parts. It’s still light outside in this dusty town, where the sun doesn’t set in summer until 11 p.m. Beijing time.The restaurant is a concrete box on the outside but fancy inside, a hidden entertaining spot for the business and government people in this northern town in Xinjiang province, where you are more likely to hear Kazakh than Chinese spoken and the culture is that of the mumin, nomadic ethnically Kazakh herders.

The baijiu stinks of regret but we are a long ways past the first shot of the night, and the entire evening—being goaded on by the camel milk princess, being toasted by senior managers in short sleeve dress shirts with shoe-polish black comb-overs, being drawn in by the well-tanned Kazakh in charge of herder relations, all of this in a fog of cigarettes and new friendship—is starting to seem like a set up for this exact moment. Properly shit-faced, improperly enthusiastic, Chen and I finish the shot. I wait for redemption, even if I can guess what comes next.

Silver cans of camel milk appear on the table, the Wang Yuan logo running diagonally across them in a blocky, stencilled font. They are supposed to erase the effects of half a bottle of moonshine, supposed to prove that their nutrition is so magnificent that there nothing it can’t overcome, not even a baijiu stupor.

It tastes mostly of dairy, with a slightly animal whiff

The cure is so effective, Chen says, that it turns his salesmen into superhuman drinkers, and so he prevents them from taking camel milk to restaurants, lest they cause havoc with lesser drinkers. There was no such ban on our dinner. Two cases of milk are propped against a wall.

I pull the tab on top of the silver can and chug. It tastes mostly of dairy, with a slightly animal whiff. It is not unpleasant. It is not alcoholic. And it doesn’t work.

***

Twenty-four hours earlier we had landed in Altay, a tiny triangle of extreme northwestern China, where the borders of Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia meet. The day before we arrived, a drunk driver had careened off the main road into the rocky, fast-flowing river that cuts through town and runs in front our hotel. But the news on our arrival was not the car rescue or the injured man. It was time for the zhuanchang.

The zhuanchang is a massive migration of tens of thousands of animals, the traditional and great summer move of camels, cows, sheep, and horses from their lower, spring pastures to the alpine grasses higher up the mountains.

These days, the zhuanchang has been at least partially co-opted by the government and used as a tourist attraction, and the hotel was buzzing with middle-aged photographers in vests who had paid dearly for the opportunity. The government’s date for the zhuanchang had been set for the following day, and across the desert scrubland and chewed-down grasslands, many farmers were forced to haul their animals to the starting point by truck to make it in time for the spectacle, cheapening, if not completely defeating, the original spirit of the tradition.

We had heard about the zhuanchang but didn’t know when it would happen, and so the timing seemed fortunate. We asked about joining, inadvertently alerting the regional propaganda bureau, which coordinates the migration, to our presence. This would prove a mistake.

The next day we made the two-hour drive from Altay to Fuhai, out of the pine forests and green fields and into the desert scrubland that stretches for hundreds of miles to the south, broken only by two freshwater lakes and the Black Mountain range. By the time we arrived, we were on the government’s radar, not a good place to be in China’s most restive province, where resentment between the Muslim Uighurs and the Han Chinese has been brewing for years.

Altay and Fuhai, by contrast, are a peaceful corner of this massive province, the size of Alaska, without any major riots or incidents to date. And yet, soldiers were installed in sandbagged encampments along the streets in the city of Altay, machine guns at the ready, and roadblocks by the police were random and excessive, forcing everyone out of their vehicles and into a small building to have their ID verified. Getting the daily newspaper was a full-day affair, from the printer to the post office where one must subscribe (it’s not available publicly) to a trip to the actual newsroom.

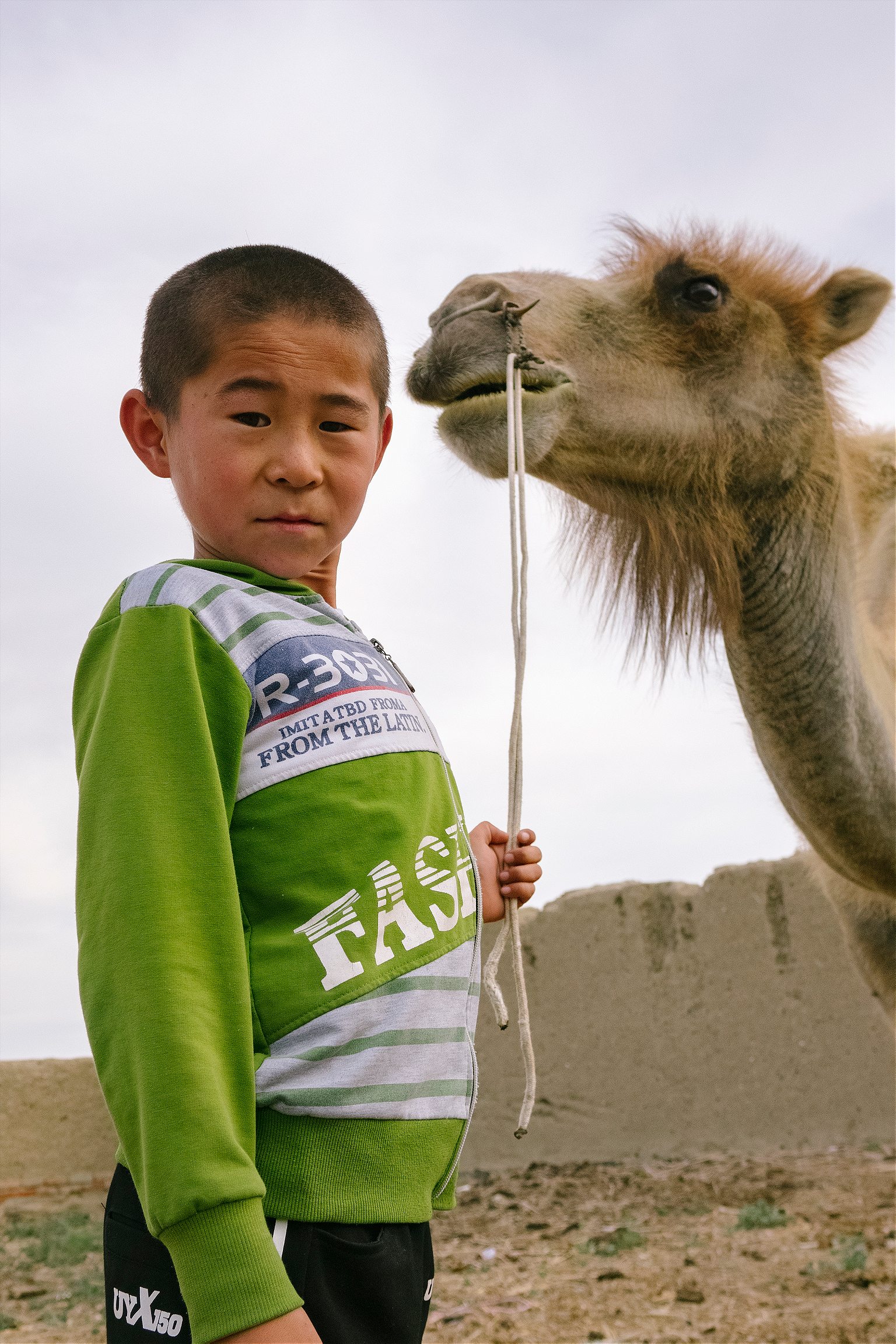

Now in Fuhai, and with time to spare, we hired a taxi driver to take us on a circuit around Ulungur Lake. The highway was smooth and black and the first traffic we encountered was a herd of camels trotting down the right lane, a young boy in a lime-green sweater running as fast as he could to keep up with them. The lakes have a high salt content, and we stopped to walk and crunch over the dried salt beds and marshy shallow ponds on its edges, white like snow with small and hardy grasses poking through the crystals.

We were a bit farther down the road, watching another herd of resting camels—their legs folded underneath them like collapsible card tables, their two humps leaning off to the side—when my phone rang. “Hi, where are you guys?” my fixer asked. “The police are in my hotel room and won’t leave until you come back.” After the excitement of seeing our first groups of double-humped Bactrian camels, up close and out in the wild, our spirits sank as we piled back into the taxi, knocking salt crystals off our shoes, wondering what we could have possibly done wrong.

We finished the circuit of the lake on the way back, the only sign of life a series of small shops selling fresh and dried fish. A roadblock appeared and we all got out and did the ID fire drill. The government is strict in this part of the world, but this seemed excessive seeing as we were just there to watch camels.

When we got back to the hotel, two plainclothes officers were waiting for us in the lobby. The older, grizzled one demanded our ID and told us to sit on the couches. A wall of poorly taxidermied fish sat behind us. Who did we work for? Why were we here? Why hadn’t we registered with the propaganda department? Why did we want to see the zhuanchang, and who would come to visit a camel milk factory? (Three to four people a week, apparently, the CEO would later tell us.) What was our boss’s telephone number? Why hadn’t we registered? Did we know we had broken the law, or were about to, by interviewing the company without the government’s permission? The younger, gentler cop wanted to know: what were our plans for tomorrow? If we weren’t allowed to visit the camel company, then what would we do? In detail? It was more annoying than threatening but there was menace in their voices. Signs extolling ethnic unity were strung all over the town, and the police were on edge. After two hours, they left. We called our contact at Wang Yuan and asked what to do. Police, she asked? Don’t worry about them.

***

For most of its recent history, fish have been the most valuable resource in this arid county, with ice-fishing the main excitement. “Camels were a transportation tool,” Chen told me, “good for carrying a couple tons of goods.” A decade ago, he estimates, there were 3,000 camels in the whole of Fuhai county, a 13,000-square mile expanse just bigger than the state of Maryland. Their milk was drunk as a medicine, given to the elderly, children, sick people, and very important guests, according to according to

Hayrat Haleymolla, the chief of the Kazakh Pharmaceutical Research Institute, and an important part of traditional Kazakh medicine. (Kazakh medicine is split into two branches: doctors who deal with bone fractures, and the “wood-and-leaf” doctors who deal with every other type of disease, all of which they believe to be contagious, and treatable by herbs and barks, as well as camel milk.) That tradition is a direct result of the rarity of the milk of a camel, which produces only a small fraction of that of a cow, and only then in the first few months after giving birth.

Today, there are 20,000 milking camels in Fuhai and the camel milk industry is booming. Xinjiang Wang Yuan Camel Milk Co Ltd is the reason.

We head out early in the morning to see the process. After miles of scrubby desert, a pair of yurts and a small dust cloud appear, the camels acting up, kicking up dirt while they wait for us. This is the spring encampment of Jengis Tohan and his hired help, a husband and wife team that do the daily grunt work.

It’s the beginning of summer and the camels are ugly. They are shedding their thick winter coats in ragged patches and their humps flop over to one side, a sign that their reserves of fat are depleted. They buck and bay, and groan a deep and sad sound, not unlike Chewbacca; they want to be milked. The camels cluster together like sheep, and the husband pulls one of the females out by the rope threaded through her nose. He leads her into a set of parallel metal bars stuck into the brown earth, an informal milking stall that looks more like playground equipment than an industrial dairy operation, and wipes her udders with warm water. His wife, in a purple velvet dress and white scarf, wheels over the milking machine—a camel-specific model designed by Wang Yuan in collaboration with a local university—attaches the suction cups, and flicks a switch. Thick, white milk streams into a stainless-steel container, but not for long. Where a cow might produce 15 liters, a camel will only give one. The herders catch, milk, and repeat, eventually straining the fresh milk into a second container, one that will go to Wang Yuan and be weighed, inspected, and credited to their boss’s account.

Satisfied to see that it is, indeed, possible to milk a camel, a question we had contemplated back in Shanghai, we let the camel milk princess lead us over to the yurts. Named Bahar Guli, or Spring Flower, she is a fine-boned and light-skinned beauty in land of strong, tan women who has become a kind of celebrity spokeswoman after a pure camel-milk diet saved her from a wasting sickness. She is dainty in her mustard-colored pants and delicate top, and plays the part of urbanite host well, fussing over the tea and snacks laid out for us. We recognize her from the Wang Yuan advertisement in the in-flight magazine we encountered on our way here, dressed in fancy traditional Kazakh wear, beaming out at us from the page.

The yurts are dusty and white on the outside, held in place with taut ropes anchored into the ground. Inside, they are resplendent, a million shades of crimson, carpeted from the walls down. Wooden ribs used to make the skeleton bend from the curved roof down to the ground in a symmetrical dome shape. A generator stands in the corner.

Nuts, dried fruit, and camel milk in every permutation sit on the table: fresh salted camel curd, hard and dry nuggets of that same curd, yogurt, fresh, fermented and dried into sheets, the table a complete explanation of all the traditional ways to preserve this precious dairy. Until Wang Yuan was founded, this was the only way camel milk lasted past the first few days of freshness. A vacuum flask of warm milk from the camels we had just seen sits at the end of the table. It is a proper Kazakh feast, passed off as just a few snacks among friends.

A man in nice slacks, a polo shirt, and an embroidered velvet prayer hat joins us in the yurt. He had been standing outside during the milking, supervising, but he wasn’t with our party from Wang Yuan. He was too clean to be a herder but too interested in the details to be stranger. As he takes a prime position on the elevated platform, directly opposite the door, we understand this is the Camel Boss. Over a bowl of gamey zhuancha, a rough and salty milk tea made with butter and camel milk, we learn that this is Jengis Tohan, no longer a herder or sheep farmer, but a budding camel-milk entrepreneur. In 2011, when Wang Yuan was founded, he used his savings and sold his flock of sheep to buy 75 camels, back when the females were cheap, and things have gone well. He’s now up to 90 camels and planning a jump to 200. The female camels are now valued at about $3,000 USD, a sevenfold increase from when he bought them. In a county where the per capita income is less than $1,500 per year, camel milk has been good to him.

From here, the milk we’ve seen will be collected by one of the roving Wang Yuan tank trucks, which roam up to 500 miles away from the Fuhai factory, collecting milk from all sizes of milking operations. The collected milk is then put through the proprietary Wang Yuan process. This is crucial. The rarity of camel milk in the past and the abundance of preserved products that we were offered go hand in hand. Without refrigeration, the traditional herders had to drink the milk fresh, or preserve it. Wang Yuan’s breakthrough, as Chen tells us later, is an enzymatic process that disables the unnamed molecules or proteins that cause camel milk to spoil. It’s only here in China, of all the camel milk-producing countries across the Middle East and Africa, that anyone has been able to break this code. “The cans say ‘Best within six months’,” Chen tells us, “but that’s just to play it safe. This milk will last up to two years.”

Like that, what once was a highly regional and limited product has suddenly become available across China, sold in specialty Wang Yuan shops in Shanghai, where I live and first noticed the phenomenon, to Guangzhou, where sales are fastest, the local population big on health and unfazed by a price tag that would be roughly the equivalent of $18 USD per can in the U.S., if you account for the difference in income. They sell in packs of six.

Since 2011, when the company opened, Wang Yuan’s revenues have grown to RMB 230 million ($34 million USD) in 2016, up 15 percent from 2015. They have more than 500 outlets, with locations in every province in China except Tibet. They recently added a RMB 90 million ($13 million USD) research and development extension to their factory in Fuhai, and a new factory in Inner Mongolia is in trial operations.

Wang Yuan is the biggest employer in Fuhai county, and to hear the CEO and local camel farmers tell it, the best thing to happen to the county in decades. Ten years ago, herders were living below the poverty line, making RMB 3,000 a year, and there was a serious social problem with alcohol and drunks freezing to death during the brutal winters. The company had done more for the growth of per capita income than any government project, and some 340 families were now raising camels, some bought with subsidies from the government, making ten times their previous annual income. “It’s not like cows,” Chen told us. “One squeeze, one fen [$0.02].” He mimicked milking a cow. “With camels, it’s one squeeze, one kuai($0.20). One squeeze, two kuai[$0.40].”

We go out to lunch at a bare-bones pilaf restaurant, where the options are rice, rice with Altay lamb, and extra lamb. When it comes time to pay, the waitress says two words—Wang Yuan—and refuses our money.

We sit with Chen as he outlines his first encounter with camels in Dubai in the early 2000s through years of visits to India, Mongolia, the Middle East and Africa, to see camels and the culture that surrounds them. To his surprise, there was barely a market for anything but meat, and even then it was small. Finally, after years of research, he commissioned a study to analyze the various proteins in the milk, looking for one that would be particularly well-suited to the cosmetics industry. It didn’t work.

Chen is a slight man with hawkish features, and he comes up to the chest of most of the herders. But decades in manufacturing on the China’s eastern seaboard, where he is originally from, have made him business savvy, and eventually he found his way to Fuhai and the Kazakhs, who already had a small population of camels. After the cosmetics failure, he took his cue from the Kazakhs and Mongolians around him, who prized the milk’s medicinal properties, and decided to pursue milk. But with villages up to 200 miles apart in some cases, collection and transportation posed a problem. Keeping the milk fresh would be nearly impossible. That challenge pushed him to develop a proprietary processing system that he says disables the molecules in the milk that trigger spoilage, allowing the milk to stay shelf-stable for 24 months, without destroying the bacteria that make the milk so beneficial in the first place. He is up-to-date on the microbiome and recent research suggesting it might be a factor in Alzheimer’s—just another disease his camel milk will help treat. He was part of a team in 2013 that sequenced the Bactrian camel genome and published its findings in the British journal Nature. Some publications report that the milk increases the body’s productions of antioxidant enzymes and may have a positive effect for people with food allergies, Type 1 diabetes, hepatitis B and other autoimmune diseases. The largest market in the U.S. are the parents of autistic children, who believe it has a calming effect on their kids.

Chen’s plans are somewhere between ambitious and far-fetched. After learning of the wild camel problem in Australia, where they run wild and disturb ranchers, he made plans to set up a slaughterhouse and import the meat to China for processing. He wants to open a nursing home in China’s far northeast that would use camel milk as therapy. Next year, he plans to apply for a medical designation for his milk, turning it, in the eyes of the law, from a food product into a medicine, though the regulations are notoriously difficult to satisfy. His employees, he says, respect him as a scholar first and not a businessman, and he emphasizes the four years of full-time research he spent on camel milk before deciding to enter, or create, really, the camel milk industry.

At 62, he might reasonably be retired after a successful career in the textile industry, but instead, he’s here, in Fuhai, 2,000 miles from home, checking in on our stomachs after our first can of the milk (the first two hours often make people’s bellies rumble) and explaining the cultural, economic, and medical background of camel milk. He tells us he’s removed 70 percent of the “camel flavor”: enough to make it palatable, in his calculation, but not enough to confuse it with cow’s milk. Indeed, the taste, on the milder side of goat milk, is the least interesting aspect of Wang Yuan’s entire operation.

Until it’s divided up like this, you don’t realize how many different types of meat there are on a sheep’s head

The next day we head to the lake. The camel milk princess’s family has a small business, her mom selling fresh camel milk from a jar and her cousin grilling fish over a slow barbecue. The family had their own lounge, a large square room mostly taken up by a carpeted platform, covered in pillows. Wolf pelts harvested by her father hung from the walls. We lazed around talking about nothing important when a familiar face walked by the open door. It was the grizzled older cop from the day before, and here we were, having a daytime get-together with the camel milk people. He did a double-take at seeing our faces, looked in to see who we were with, and then smiled. He never said a word.

On our second night, the banquet was held in a herder’s modest home, outside of town. The same embarrassment of dried fruits and dairy products were laid out for our arrival, and off to the side, on the couch, I could see Wang Yuan’s senior management starting to remove the packaging from the baijiu bottles. By this point, the CEO had given up his conceit about camel milk inhibiting the effect of alcohol, and he leaned over and whispered to me, “We need a strategy.” He came up with an elaborate toasting ritual, using his god-like status among these herders to force toast after toast on them, until their eyes turned red and the room got loud. My fixer, seated to the CEO’s left, survived by pretending to take a sip of tea after each toast, and then coyly spitting the baijiu back into the tea. I drank it straight and tried to eat as much as possible.

The better part of a roast sheep arrived on the table and the snacks were cleared away. A round and jolly camel herder named Jiger Hurmet, a big guy who had already imbibed enough baijiu for all of us, did the honors. He pulled out a long pocket knife and divided up the meat of the sheep’s head with the practiced patter of a wedding officiant. “To the beautiful woman over here, an ear, so that she may better hear and understand her husband,” he started. “To our new singing friends over here, the meat from the upper palate, so that you may use it to speak the truth about us.” Until it’s divided up like this, you don’t realize how many different types of meat there are on a sheep’s head. I think I was given part of a cheek. I’m not clear how it was supposed to benefit me.

By this point, it didn’t matter. The night was getting sloppy and camel milk was not going to stop it. Music helped. The Kazakhs are famous for their singing, and out of nowhere, a dombra, a Kazakh lute, appeared.

Resting it against his ample belly, the intoxication fell away and the table fell under the trance of Hurmet’s booming voice and folk songs, which carried through the house and out into the courtyard. Halfway through, he made a solemn speech about a song that was dedicated to CEO Chen, the man whose company had single-handedly raised his standard of living and brought him to the feast that night. He broke into a mournful verse and began strumming both strings in rapid succession. It was a sad story, a fable of a young camel that was separated from its family, lost in the desert, a parable about never being able to go home again.

When he finished, the living room erupted in applause, and Hurmet immediately stood up to offer Chen another shot of baijiu. The night continued on like this, getting hazier and hazier until finally it was time to go. Hurmet dragged me out of the house, through the courtyard and into the backyard, a pitch-black area lit from above by the thousands of stars in the sky, the type of view you only get far from a city. He pulled me into a big bear hug and slurred into my ear. “Look at this place. This is where I’m from,” he said. “Tell people about what Chen has done for us.”