The rabble-rousing musicians of La Solfónica provide a soundtrack to Spain’s many protests.

One March evening last year, a ruckus of tear gas bombs, angry megaphones, and a frenzied crowd was accompanied by operatic melodies at Madrid’s Plaza de Colón. Hundreds of musicians had gathered around a grubby water feature to serenade more than 36,000 protesters who had marched on the capital from all over Spain to express discontent with the conservative administration’s severe austerity measures.

The melee peaked as singers bellowed out the chorus from Giuseppe Verdi’s “Nabucco”—an opera written in 1841 that has become a revolutionary anthem in its own right.

“I didn’t know what to do,” recalls Sonia Megías, a Madrid-based composer who conducted the ensemble. “I was cutting [the music] and asking the choir and orchestra, ‘Shall we run away, or continue, or what?’” as riot police clashed with demonstrators just meters behind her. Instead of fleeing for cover, the makeshift orchestra brandished violins, cellos, flutes, and sheet music high in the air, chanting, “These are our weapons!”

Although the term “protest music” conjures images of Baez, Dylan, Marley, Molotov, and many more, its roots lie in the classical traditions represented by La Solfónica, a rabble-rousing group that plays at demonstrations across Madrid.

It grew out of a protest performance on May 15, 2011, the day for which the “15-M” movement is named. Created in the run-up to regional elections, its members, inspired by the Arab Spring, demanded change in a system dominated by the conservative People’s Party and the center-left Socialist Workers’ Party, which was in power at the time. During months of demonstrations, people camped out on plazas around Spain—a tactic subsequently adopted by the Occupy movement in the United States.

Years later, Spain continues to grapple with more than 23 percent unemployment, corruption, and a stagnant economy—now under a conservative government—and La Solfónica is still going strong. Its name plays on the Spanish words for “sun” and “phonics,” and references Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, the square that became the focal point for 15-M protests.

It is a loose, open collective of singers and musicians, both hobbyist and professional, with a horizontal structure that has no leaders. Regular rehearsals are organized via email and Facebook. At one practice session in October, about 35 people gathered in a dilapidated school; numbers at protests can vary depending on who’s available.

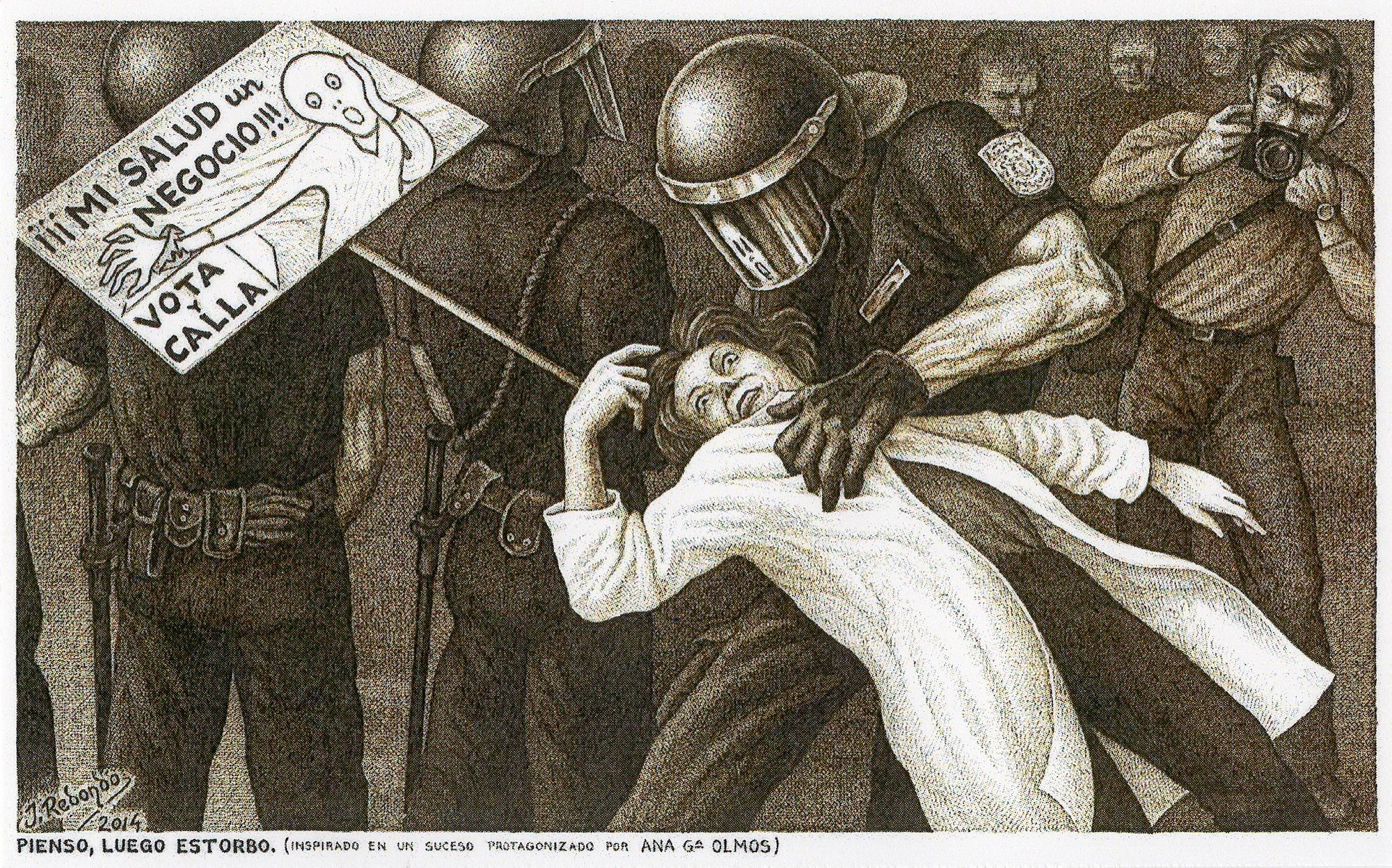

The fierce confrontation on Plaza de Colón in March last year is not the only time La Solfónica has witnessed heavy-handed policing. At a protest against the privatization of health services in June 2013, officers beat singer Ana Olmos outside the mental hospital where she works as a psychiatrist.

“I was there with my white medical coat. Riot police surrounded us as the demonstration was ending and attacked me,” she recalls. A lawyer who participates in La Solfónica helped Olmos gather evidence from journalists, photographers and others present—as well as images of her injured head, ribs, and right hand—but a judge dismissed their case.

The orchestra’s repertoire features classics from the national canon as well as original compositions and older works such as “Va, pensiero”—the chorus of Hebrew Slaves from Verdi’s “Nabucco.” Premiered in 1842 in Milan, the opera is based on biblical stories about the Babylonian attack on Jerusalem and King Nabucco’s enslavement of the Jews.

In act three, the exiled Israelites sing “Va, pensiero,” longing for “the sweet airs” of their homeland, “so beautiful and lost.” With northern Italy under Austrian rule, the work was interpreted as a bitter parable of the local situation.

“At that time, it was a political-military occupation, but now the forms of occupation are different: You could say we’ve been living with an economic-ideological occupation in recent years,” says David Alegre, a professional violist who directs La Solfónica. He believes democratic institutions are being “repressed” by authorities and the two-party system.

“That’s why Verdi’s message is still completely valid—we want to get back the liberty of action to decide what kind of country we want,” Alegre continues.

“Va, pensiero” is effectively sung with one voice using simple harmonies. “Nabucco” played a significant role in stoking anti-imperial fervor in its early years, culminating in March 1848, when Milanese rebels drove the Austrians from their city after five days of street fighting. Although the occupiers wrestled back control six months later, the die had been cast: Italian unification, or “Risorgimento,” was ultimately achieved in 1871.

Three years later, Verdi was made a senator to recognize his symbolic role in the struggle.

Italy is not the only country in which opera was a catalyst for change. During the Bourbon Restoration in France—a period of hereditary monarchy between Napoleon’s fall in 1814 and the July Revolution of 1830—Daniel Auber’s “La Muette de Portici” (“The Mute Girl of Portici”) was performed at the Academie Royal in Paris.

Debuting in 1828, it was loosely based on the story of a 17th-century Neapolitan uprising against Spain, led by a fisherman, Masaniello, whose mute sister is seduced by the Spanish viceroy’s son. But its message was not intended to foment unrest: As mob rule descends in Naples, the title character throws herself into the fiery inferno of Mount Vesuvius, which has erupted as figurative punishment for the chaotic consequences of resistance.

Academic Karen Pendle writes that, in “La Muette,” “the losers are not primarily the leaders but rather the masses of people who have been taken advantage of by both sides.” By allowing the show to run, French authorities hoped to instil that sense of fear in the minds of the bourgeoisie.

But the ploy backfired: In July 1830, King Charles X was overthrown. In “The Oxford History of Western Music,” Richard Taruskin describes how audiences identified so strongly with “powerfully portrayed peasant revolutionaries” that the opera can be regarded as “a virtual ‘accessory before the fact’ to the revolution… in which political power was decisively wrested by the bourgeoisie from the aristocracy for good and all.”

One month later, a performance of “La Muette” in Brussels changed the history of Belgium.

As the opera came to an end with “Amour sacré de la Patrie,” the audience began to sing along and flocked into the streets, where a large crowd had gathered. They swept into government and newspaper offices, and plundered the municipal armory for weapons; momentum spread across the country and Dutch imperial forces soon withdrew.

Although historians dispute whether these events in Brussels happened by coincidence or design, the power of music had been established. “Opera could now not only mirror but actually make the history of nations,” Taruskin writes. “In extreme cases it could even help make the nation.”

La Solfónica has also dabbled in opera, staging “El Crepúsculo del Ladrillo” (“Twilight of the Brick”) in 2013 to mark the second anniversary of 15-M. That year, another action saw a flash mob sing The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” to lift spirits at an unemployment office.

Other contemporary numbers include “Rebelión.” It borrows the catchy melody from “Ja Veux,” a global hit by French songwriter Zaz, reimagined with original lyrics that demand “real democracy,” social justice and a secular republic.

This was one of the songs performed on a blazing October day at Carabanchel prison south of Madrid. Although the notorious Franco-era facility was demolished in 2008, the land remains barren and scarred; a detention center for undocumented migrants now stands adjacent to the empty lot.

A strange circus-like dome atop the gatehouse loomed over Solfónica singers brave enough to face the heat with a few hundred people marching to demand better treatment for detainees.

“This is a group of action,” Alegre says. “Perhaps our work is more important in smaller demonstrations… You’re giving people energy to keep fighting.”

“People always love hearing music at protests—songs that talk about evil, justice, and the liberty we are losing,” adds Luisa Gutiérrez, a veteran member of the ensemble.

In the early 1940s, while La Carabanchel was under construction, a different kind of masterpiece from the classical protest canon was created at another dark, barbaric institution across the continent in Germany.

French composer Olivier Messiaen wrote his visionary “Quartet for the End of Time” while incarcerated at Stalag VIII-A, a Nazi prison camp that lies in modern-day Poland. It premiered outdoors on a rainy night in 1941, with Messiaen’s piano accompanied by three fellow musician inmates on clarinet, violin, and cello—all using dilapidated instruments obtained by a sympathetic jailer.

It’s an unconventional group. The score alternates between duo, trio, and quartet sections, with a third movement of mournful birdsong played on solo clarinet. Winding melodies spun from minor motifs tie the piece together; Messiaen was inspired by a passage from the Book of Revelations in which angels descend to earth.

This may seem a far cry from La Solfónica spreading rebellion on the streets of Madrid, but Messiaen’s magnum opus pulses with revolutionary zeal. The elaborate, unpredictable arrangements, haunting high notes and extreme dynamic range are all ways of protesting his situation and the conflict that caused it. Upturning convention is a potent creative tool for channeling frustration at the way things are. Dissonance is dissidence.

The “End of Time” not only refers to the composer’s iconoclastic use of experimental rhythmic ideas, but a deeper desire to end life as Messiaen knows it and begin a new chapter in the history of humanity.

“The language of music is a little hard to grasp, and we can’t always understand it even if the music has words,” says David Alegre of La Solfónica. “But when we feel the energy generated by music, which ignites our passions, we can connect and understand ourselves in the search for a common path.”

Listen to the audio story: