On the 50th anniversary of Che Guevara’s secret mission to Congo, a photographer revisits the past.

On a November night in 1965, Che Guevara quietly boarded a small boat on Lake Tanganyika. It was the end of his secret mission designed to spark a revolution in Congo. Several months earlier, he had entered the country secretly with 100 Cuban combatants to support an insurgency against the imperialist forces that had overthrown Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, the socialist Patrice Lumumba. He failed miserably, however, and the mission was disavowed by Cuba as an embarrassment. Fifty years later, the photojournalist Jan-Joseph Stok is retracing Che’s footsteps to see how his loftier ideals of liberty, equality, justice and self-determination resonate with the Congolese of today. Along with the filmmaker Ben Crowe and the graphic designer Teun Van Der Heijden, the Dutch photographer is embarking on a journey to Tanzania and Congo that will materialize in a multimedia project called “Che in Congo.” He joined R&K from his home in Amsterdam.

Roads & Kingdoms: Why did Che Guevara go to Congo?

Jan-Joseph Stok: Because he was trying to get people to decide for themselves. He was trying to fight a war against the imperialist powers. But for more than 30 years, Cuba kept this mission a secret because it was a failure. They didn’t want people to know that a revolution could sometimes be unsuccessful.

R&K: How did you learn about it?

Stok: A bit by accident. I overheard someone listening to an audiobook about Che in the Congo. I work regularly with a graphic designer called Teun van der Heijden and I had told him I was going to make a retrospective book about my 10 years of work in the Congo. He said: “why do you want to make a book that so many people have done? What more are you going to bring?” So I came up with this idea of Che Guevara in Congo as a way to tell the story in a different way.

R&K: What particularly interested you in this story?

Stok: A lot of the things that Che described about Congo are things that I also found relevant today. For example, that the Congolese are not fighters in essence. They are pacifist people, and that’s why a lot of different countries are exploiting them. That was Che’s struggle, because he would have liked them to fight for their destiny. That was his frustration. A lot of the problems that Congo faced at that time are still the reality today.

R&K: Did you know a lot about Che Guevara before the project? Were you a fan?

Stok: I’m a journalist, so I’m not taking sides. I’m really not a fan of Che Guevara but I’m very interested in him as a person and also in the way that his journey and his philosophy compare to nowadays. I’ve been to nearly every region of the Congo, I’ve covered a large range of topics, from the war and its victims to deforestation, pygmees and boy scouts and oil. This is a new way to tell the story of Congo and attract probably a bigger audience who would not have been interested otherwise. It’s also more of a personal project, which gives way to a more creative imagination.

R&K: What traces of Che’s mission in Congo are visible today?

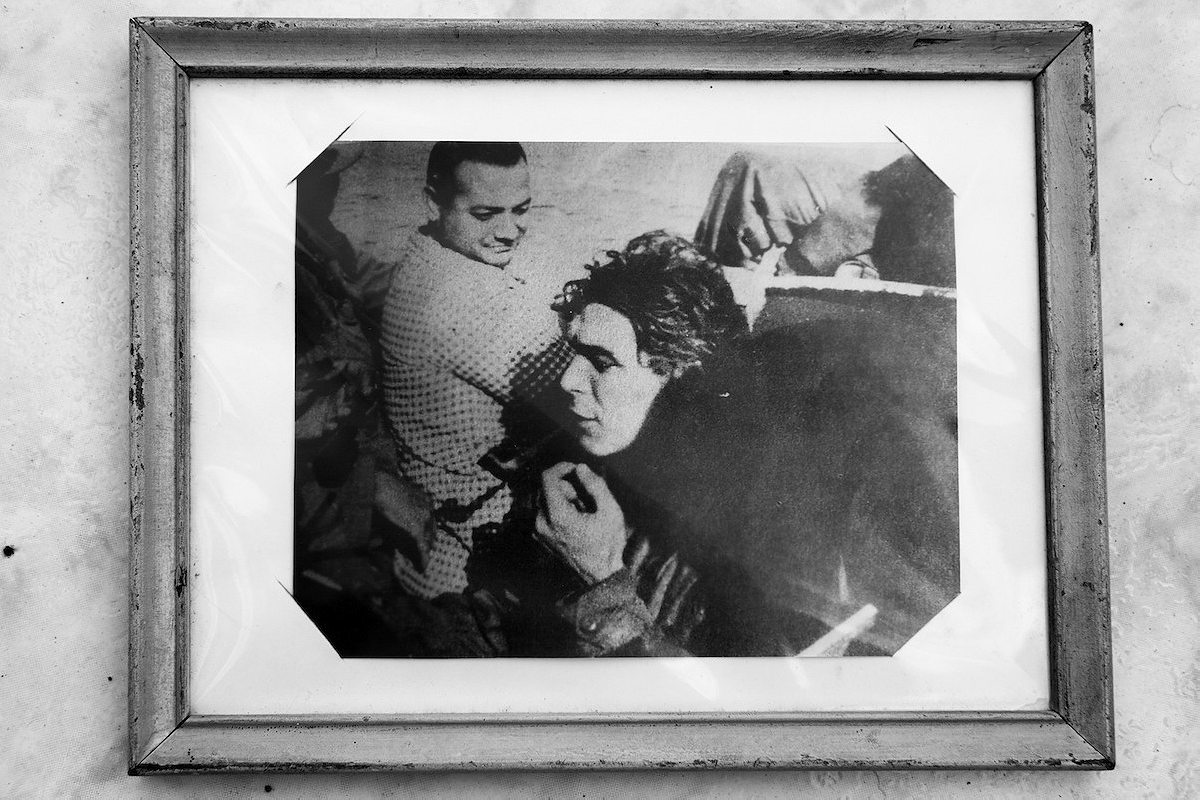

Stok: That’s what we are going to find out. As of now, we’ve gone to Cuba on a research trip. I spoke to Che Guevara’s son, Camilo Guevara, who gave us the authorization to work on the story–because without his permission we would have been stopped at some point. At the same time, we were testing the story to make sure it’s relevant, that it’s still alive today, that there are still people who can tell us about it. So we interviewed a lot of the combatants who were with Che in Congo, the second in command Victor Dreke, the people who tried to rescue him–because he was rescued by a team from Cuba. Those combatants had a lot of personal archive images, which they allowed us to photograph. Because it’s a little-known story, and because it was kept secret for so long by Cuba, we didn’t know if they would be open to talk. A few have written about the mission, but only recently have they accepted to open up on this part of the country’s history. I think Cuba realizes that all these things from the revolution are fading away slowly, so they understand that it’s important for history to be told and that’s why they agreed to speak to us. Even though Che didn’t succeed at the time, he had strong values. For example, he was very careful not to exploit the Congolese. He believed that his Cuban fighters should have the same rights and the same advantages as the Congolese fighters he was trying to train.

R&K: What is the relationship today between Cuba and Congo?

Stok: A week or two before we arrived, Joseph Kabila was in Cuba. The two countries still have a strong relationship. Apparently they still send a lot of doctors from Cuba to Congo. In Havana, there is a memorial of all the leaders that were close Cuba, and Laurent Kabila and Lumumba are both present.

R&K: Did the Cubans you meet know about Che’s mission to Congo?

Stok: Only very few people know about it. Actually, for one of the combatants we interviewed, Positivo, it was the first time he ever talked to anybody about this mission. And he only did because he received an order from his general to speak to us. The thing is that Che Guevara is still a god in Cuba. That’s very clear. Wherever you go, you feel it.

R&K: Where else will you be going to report on this project?

Stok: We are planning to do the exact same trip as Che, so we’ll start in Dar es Salam in Tanzania and we’ll take the train through the whole country – that’s also how the fighters and Che traveled – until we reach Kigoma, which is where Lake Tanganyika is. Then we will take a boat across the lake and we’ll retrace the route inside South Kivu and Katanga, and we will go to all the camps and all the battlefields, all the places he went. Then, we will probably go back to Cuba because although we already have archive images from the combatants, it’s Camilo Guevara – apparently a photographer himself – who really has the key to all of the Che Guevara pictures taken during his time in Congo. I think that he will only open up totally to us once the work is done. And that will make the project even more exclusive.

R&K: It’s not easy to photograph the past. How will you overcome this challenge?

Stok: The beauty of Congo is that sometimes you feel the vestiges of the past. We have precise descriptions of the places Che went to, so we’ll need to use our imagination to retrace those moments. With battlefields, for example, you feel the atmosphere, but you have to grab it with photography without anyone being there. What we’re also going to do is use different photographic techniques, so for example, we’ll be using the exact same camera that Che used 50 years ago: a rangefinder Nikon 35mm 1965. We will also use 360 degrees photography to capture the entire feeling of a place.

R&K: Do you expect to meet people who were there at the time?

Stok: Yes. We already have the names of some people that we will try to find – rebels who were with Che. There are some key people like the ambassador of Cuba in Tanzania, but we also just want to find some regular people, give them a voice about how they see the past, how they see the present and the future. One of the beauties of this project is this randomness. A lot of journalists – me included – go to these places with an assignment and already know the kind of pictures they need to bring back. This project is open to the unexpected.

R&K: You mention the future of the country a lot. How do you think that looking at the past, at something that happened 50 years ago, will help think about the future of Congo?

Stok: Because, you know, history keeps on repeating itself in Congo. If you go there regularly, you will see that there are waves, that over and over a new group will try to exploit Congo. By trying to understand the past, we can hope for the future. I’ve been to Congo more than 30 times, so there’s a continuity of things I saw around me while working there and now I want to dig deeper in a different way. Once in a while, you have these dreams and these projects that you really believe in, and dreams are made to be realized. So sometimes people might say you’re crazy, but you do it anyway because you just believe in it. I feel like this is what I need to do right now.

R&K: Will you be working in Congo after this project?

Stok: Yes. I have Congo very deep in my heart so I will not turn the page after this project. I feel like it’s my obligation to go back, to tell the story over and over again, but to try to bring it in a different way so that it will still be heard or seen. I know a lot of local journalists and one of the things that they’re fed up with is that it’s the Western media that is trying to write their history. I think it’s time for the Congolese people themselves to write their history. This project is a bit more about that. Giving a voice to the people in a different way. Not always as the victims but as people who think themselves about their country.

You can help Jan-Joseph Stok realize “Che in Congo” by donating to his Kickstarter campaign.